Vampire Weekend: The Music Never Stopped

This article originally appears as the cover story of the June 2019 issue of Relix. Subscribe before July 1 here with code SUNFLOWER to get $5 off.

Six years after dropping their previous LP, Vampire Weekend dig into their “jam-adjacent” aspirations and new band realities on a cosmic fourth album inspired by East Coast nostalgia, hip-hop production and the good ol’ Grateful Dead.

It’s a sunny day in Hollywood, Calif., but Vampire Weekend’s Ezra Koenig is glad to be indoors, at his management’s office, sitting comfortably on a couch where The White Stripes, The Shins and Cold War Kids have all sat and pondered their careers. The room is sparse but somehow laced with muted excitement, like a waiting room for those about to rock. Koenig still has to wait another three weeks before Vampire Weekend’s Father of the Bride, his group’s fourth LP and first in six years, hits shelves, and it’s impossible not to feel like he’s living inside the metaphor—the album is the bride. And he’s about to give her away. It’s a big moment.

All ceremony aside, the hope is that Father of the Bride will join David Bowie’s Hunky Dory, Queen’s A Night at the Opera, The Who’s Tommy and Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town as bids for longevity; those albums all elevated their respective makers from johnny-come-latelies to legacy artists. Not coincidentally, they’re also all fourth albums.

“One burst of good ideas can get you through three albums,” says Koenig, nodding, keenly aware of where the conversation is going. Koenig is bright, measured and lives a self-examined life that prizes intent and awareness.

So he knows: There’s no shortage of bands who have made three successful albums only to fold into the arms of oblivion. Others have suffered fourth album losses, devaluing their previous hits into little more than throwbacks. Indeed, the express lane leading from heat-seeker to blast from the past is well traveled and takes only a few short years to traverse.

That cruel destination scared the shit out of Koenig. As a student of music who always does his homework, including the extra credit, he couldn’t help but see the precipice where Vampire Weekend stood at the end of the cycle for their third album, 2013’s Modern Vampires of the City, and feel the wind blow up from below.

“Over the course of three albums, we went on a journey from youth to the end of youth,” he says. Koenig had to put a lot of time and effort into making sure that each of those three albums was unique, that each of them broke new ground. Their self-titled breakout was quirky and—despite some critics who ostentatiously grappled with the disparate elements—it made most indie bloggers very, very happy to have something new to talk about. The music was fresh, it was different and it catapulted Vampire Weekend from nowhere to everywhere, and fast.

Their second album, 2010’s Contra, wasn’t a departure, but did add depth, foraging from a wider swath of the musical landscape for an agreeable patchwork of synth-pop, ska, worldbeat, electronic, hip-hop, punk-pop and indie-rock. The band’s audience continued to grow in numbers and, by their third release, they were getting recognition from their peers and elders as well. They had become established. It was an arc that, essentially, mirrored Koenig’s 20s.

“It’s not a shocker to me that some people took the third album, Modern Vampires, more seriously,” Koenig admits. “Because you stuck around, you grew, you hopefully maintained some quality—you get these pats on the back that nobody is going to give you when you’re new.”

He stops to take a sip of coffee and reflect. “That all felt good and it’s gratifying. But then there is that funny feeling that happens the moment you’ve finally achieved what you’ve been dreaming of: The next day, you’re like, ‘Well, what do we do now?’”

The answer, for Koenig, was nothing. As Vampire Weekend’s creative captain, he had no destination in mind while the ship bobbed across open water. He let go of the wheel, but wouldn’t let anyone else take it either. Without any land in sight, it didn’t matter. They had time to drift and, with no fuel in the tank, it was the best possible thing for their long-term survival. A few years passed.

Koenig knew that if he wanted to—or if he wasn’t careful—he could write a fourth album that sounded a lot like the first three. But why bother? The fast track to irrelevance is redundancy.

So, after Modern Vampires won a Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album, with the obligatory whirlwind tour that followed, Koenig took some time off. He stayed somewhat active, creating an animated series for Netflix (Neo Yokio) and working on his podcast (Time Crisis). He had a baby. But the Vampire, which he named after an abandoned film idea he had back in college, was always there.

“It took some thinking to say, ‘Yeah, so, what do we do now?’” says Koenig. “The stakes were lower in the sense that we probably could’ve released a totally boring album and we’d still sell some tickets.”

It’s true—at a certain point, even if you release a bad album, as long as you still play the hits (say, “Oxford Comma,” “Ya Hey,” “The Kids Don’t Stand a Chance,” “Hannah Hunt,” “Step”—there are plenty of them) fans will come to the dog-and-pony show, take Instagram clips of their favorite songs and recall the time in college when Contra first came out and it was playing at that party the night of…

“Actually, maybe that’s when the stakes are higher,” says Koenig, looking down at the coffee table while gears visibly move inside his head. As he grew older and progressed through his 30s, he needed to figure out a way to progress the band as well, or else risk creative death—not just commercially, but personally.

“I’m not talking about the critics or the fans, but if you can make a fourth album just for yourself, that gives you some of those feelings you had in your early 20s when you wrote a new song that wasn’t quite like anything you’d ever done before…” he says, pausing to think. “Then you can see a path forward.”

That path has a destination called community. The Vampire Weekend fans who live there are lifers. They get to experience a band that has grown with them since graduation, that has been with them as they struggled to get jobs, families, a home, and then has stuck with them well into their 30s as they’ve gone on vacations and put down roots and started to have kids of their own. “That’s when you realize there’s something deeper than infinite growth,” Koenig says. For those who have gone the distance with them, the band’s history becomes a shared history—and Vampire Weekend becomes an experience.

Koenig makes an observation about his personal life as a metaphor: “I don’t need to be surrounded by strangers or casual acquaintances all the time anymore,” he says. “I would rather have a core group of friends and just be around the people that I’m close with. I’ve got less FOMO than I ever had in my life.”

With an important album release around the corner, and all the unimaginable pressure that must bring to any artist, Koenig appears remarkably at ease—relaxed, prepared, confident. He seems familiar with the couch in his team’s office that he’s sprawled out on, comfortably, while his managers are presumably at their desks, behind closed doors. But there is an elephant in the room and that’s the absence of founding member Rostam Batmanglij.

In 2016, Batmanglij quit the band. His departure should probably be a big deal because he helped define Vampire Weekend’s inimitable sound. And yet, Koenig and his two bandmates—drummer Chris Tomson and bassist Chris Baio—all seem nonchalant (or, at least, respectfully tight-lipped) about the change.

Koenig insists that there’s not much to it and doesn’t have anything more to add about the departure, other than he always knew the day would come—Batmanglij had additional aspirations from the beginning and never looked at Vampire Weekend as his own life’s work. He adds that Batmanglij’s creative identity was never tied to a specific instrument; in fact, he and his longtime friend were never even married to the concept of Vampire Weekend being a band.

Significantly, Batmanglij still contributed to Father of the Bride. Perhaps he’ll continue to contribute to future albums. “The split was amicable,” as they say. Perhaps the band’s casualness isn’t stoicism so much as it is adjustment—after all, for them, the change happened several years ago. They’ve had time to acclimate. More important, initial concerns were squashed by the time they started rehearsing the new material.

“I don’t need to be surrounded by

– EZRA KOENIG

strangers or casual acquaintances all the time, anymore. I would rather have a core group of friends and just be around the people that I’m close with. I’ve got less FOMO than I ever had in my life.”

“As tectonic plates shift, there’s some settling to be done,” admits Tomson, hesitantly. “Vampire Weekend, as an entity, was going to have to figure out change and figure out growth and figure out a lot of things—regardless of Rostam leaving or staying.”

Tomson’s enthusiasm, when reflecting back on the process of forging ahead, is undeniable. “I’m not pumped because of something that has ceased to be,” he clarifies. “I’m pumped for a new chapter to start.”

Still, any initial unease from fans on the outside is understandable: Vampire Weekend has always been Koenig’s Frankenstein; his songs, his vision. But Batmanglij was usually the one next to him, in the producer’s chair.

With Batmanglij gone, they were no longer a quartet. So they expanded into a septet instead, bringing in guitarist Brian Robert Jones, multi-instrumentalist Greta Morgan, drummer/ percussionist Garrett Ray and keyboardist Will Canzoneri.

Jones, who had previously played bass with Gwen Stefani, represents a new generation of fans who grew up on Vampire Weekend’s music. “I listened to Vampire Weekend when I was in high school and, now, I’m playing in the band,” he says with a grin.

“There was something totally unappealing about finding a person to just do the parts he played, as he played them and all that,” Tomson says, supporting Koenig’s instinct. Adding four musicians instead of one allows the band to play things live now that they never could’ve before, by sheer virtue of all the extra limbs.

“The idea of rolling out there with four people feels so anemic now,” says Koenig. “It doesn’t make sense to me.”

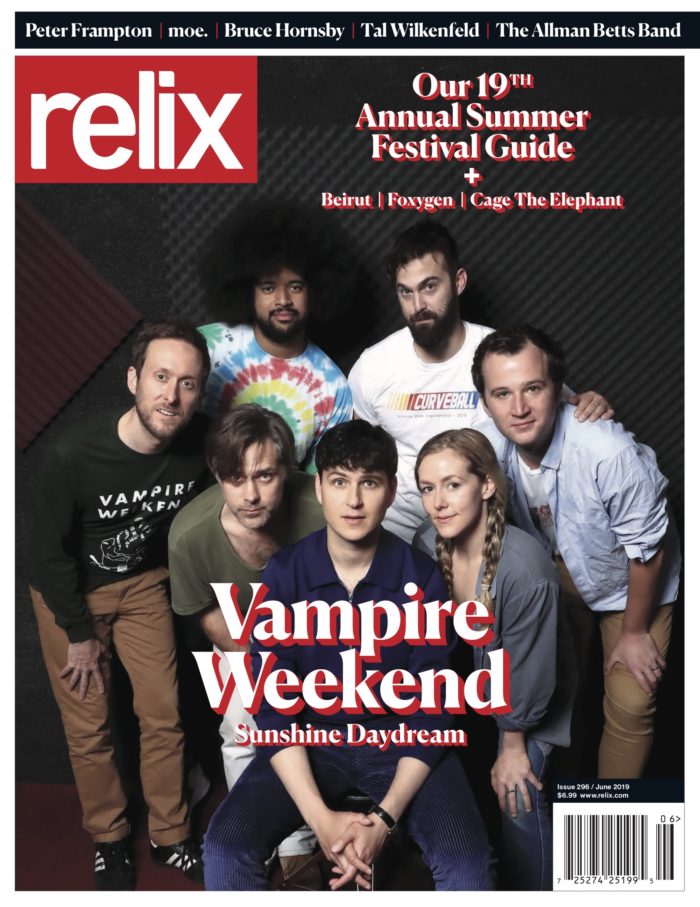

Vampire Weekend 2.0: Ezra Koenig, Chris Baio, Will Canzoneri, Brian Robert Jones, Greta Morgan, Garrett Ray, Chris Tomson (clockwise from center top) (photo by Jeff Kravitz)

In the studio, Koenig has always favored having a collaborator for checks and balances so, in Batmanglij’s absence, he reached out to other producers, including Mark Ronson, BloodPop and longtime associate Ariel Rechtshaid—all of whom come with impressive track records. The Internet’s Steve Lacy guests on a song, and vocalist Danielle Haim appears on a number of them. Hans Zimmer even has a writing credit.

Koenig notes that, even though he and the Chrises will always have their shared heritage, it did not feel representative of their true creative process to simply have a picture of the three of them in the album’s liner notes. He admits that some of his production partners are “kind of ” in Vampire Weekend, but including a picture of everyone involved in the process would look like a “middle school” photo so they went with a picture of Haim for the Father of the Bride vinyl gatefold.

“When I listen back to this album, I think there’s elements of all three of the albums, plus something new,” says Koenig. And to be sure, Father of the Bride is an evolutionary album for Vampire Weekend—the bridge between their youth and middle-age.

Without really even intending to, Koenig relocated to Los Angeles in a move that happened slowly over a couple of years—a move he still talks about ambivalently. His romantic partner, actress Rashida Jones, lives in LA. The two of them had a child together last summer. And his core bandmates, Tomson and Baio, also moved to the area, each for their own reasons. So, even though he considered himself a lifelong New Yorker and had his own apartment, Koenig found himself living in LA.

“So much of this album is about analyzing my own nostalgia for an East Coast ‘90s feeling,” says Koenig, who finds it ironic that early reviews have decided that Father of the Bride has a California soul to it. “I picture myself being exiled in California, thinking about being back in Vermont in 1997.”

Indeed, Father of the Bride is chock-full of nostalgia and homesickness, dressed up in various disguises. There’s the pensive “Big Blue” (“I was so overcome with emotion/ When I was hurt and in need of affection/ When I was tired and I couldn’t go home”), the patronizing “This Life” (“Baby, I know pain is as natural as the rain/ I just thought it didn’t rain in California”) and “Sunflower,” which betrays Koenig’s preference for the overcast Northeast weather over the perpetual Southern Californian sun (“No power can compel you/ Out into the daylight/ Let that evil wait”).

“As tectonic plates shift, there’s some settling to be done. Vampire Weekend, as an entity, was going to have to figure out change and figure out growth and figure out a lot of things—regardless of Rostam leaving or staying.”

– CHRIS TOMSON

But the East Coast that Koenig pines for might not exist anymore. It’s not just about geography; it’s a longing for a time as much as a place. As an example, he brings up the Wetlands, the New York City nightclub that, in the 1990s, every Deadhead in the country knew about and every jamband fan within a certain radius called their second home. “The venue represented a specific type of East Coast person who generally didn’t just like the Grateful Dead, didn’t just like Phish, didn’t just like Dave Matthews,” says Koenig. “They probably would like at least one of those bands, but they were also interested in hip-hop and interested in music from the ‘60s and ‘70s. It almost represented an approach to music, an attitude toward music, and an interplay between musicianship and composition. There’s a million ways you could describe it, but there was something about it—it was a pristine moment.”

Koenig fondly recalls seeing the Greyboy Allstars, who he covered in his high-school band, at Wetlands, shortly before the venue shuttered in September 2001. “By the time Vampire Weekend were playing shows,” he says, “it was already a faded memory of New York.” His nostalgia for that halcyon era is reflected by the fact that he recently watched a documentary on the nightclub’s history, Wetlands Preserved. [The 2006 film on Relix publisher Peter Shapiro’s former club was directed by Relix editor Dean Budnick.] Koenig explains that he doesn’t really get a chance to discuss this with journalists, and he seems eager to talk about it.

“The East Coast is kind of my ancestral homeland,” he says.

Any optimism in the lyrics on Father of the Bride is found in those moments fraught with sentimentality for both youth and home. Anything dealing with today or tomorrow is shaded with anxiety and detachment—or, perhaps, a guilty kind of acceptance. In the album track “How Long,” the narrator asks, “How long till we sink to the bottom of the sea?” without sounding too worried or concerned. It’s a resigned acknowledgment that time passes and things change.

“As I get older, I realize the art form is not the song. It’s not the album. It truly is the career,” Koenig muses, spit-balling as he goes. “It’s the discography. You could go back and debate what Kanye West album might be your favorite, but it doesn’t matter. You can have different entry points, but Kanye produces a body of work that changes and grows and, yet, feels connected. To me, that’s the highest thing to aspire to. What’s exciting is that can you keep adding chapters to the book—you’re reading the same book, nobody’s confused, but you are progressing through a narrative.”

It’s an equally sunny day in Glendale, on the backside of the iconic Hollywood sign, Griffith Park and Tinseltown just beyond. Here, on the wrong side of the hill, all seven members of the current, touring version of Vampire Weekend are gathered in an industrial park, surrounded by warehouses, factories, a couple auto part stores and not much else. Welcome to Vampire Weekend’s rehearsal space. The band is taking a 30-minute break from running through the new material, pausing only to eat lunch. Rehearsal ends at 3 p.m., but it’s still going to be a long day—after rehearsal, the guys have to stick around for the joyless task of filming a video for the song “This Life.”

A photographer sets up for some band portraits and, upon meeting Koenig, confesses that he’s a huge Deadhead and that the new single, “Sunflower,” reminds him of the Dead’s “China Cat Sunflower.”

“Oh, really?” asks Koenig, only slightly surprised. “Some people have said it sounds more like Phish.” They start talking about Jerry Garcia’s “China Cat” riff and the song’s chord progression, and Koenig posits that echoes of both elements seem to pop up everywhere, even in places where they’re not. He offers that another single from this album, “Harmony Hall,” has also received that same comparison.

But then there’s this: When Vampire Weekend went on BBC Radio 1 recently to promote “Sunflower,” they performed a cover of Post Malone and Swae Lee’s hit of the same name instead. During the intro, Koenig referenced a guitar lick from “China Cat Sunflower” and then teased Vampire’s own “Sunflower” (and “Harmony Hall”) during the instrumental breaks. Furthermore, on the new album, Koenig used an envelope filter effect that gets him undeniably close to Garcia territory, despite the foreign cover song. It was a clever prank and a deliciously layered musical pun.

All of this is surprising, considering that Vampire Weekend was once part of a wave of indie-rock coming out of Brooklyn 10-15 years ago that rejected guitar solos and that instinctively revolted against any notion of “guitar rock,” let alone “jams.”

On the day of the band’s rehearsal, Rolling Stone published an article proclaiming that the guitar solo is officially dead. “That kinda makes it cool again though, right?” says Koenig with a knowing grin.

Inside the rehearsal space, Koenig takes out his phone to snap a shot of Nikki Sixx’s autograph, written in Sharpie on a cymbal on display on a wall in the hallway. There’s also kombucha in the vending machine. It’s that kind of studio.

The band is set up facing each other in a thin but long rectangular room, with a lighting truss hanging from the ceiling and soundproof walls. With seven people in the touring configuration, the band now has two drummers which, in itself, begs additional questions about a new or renewed Grateful Dead influence.

“Like any kid growing up on the East Coast—and like any kid who likes rock music—I was familiar with the Grateful Dead,” Koenig explains. “I liked them and I had my little phase as a tween wearing Grateful Dead shirts and being interested in it.”

But, also indicative of the time and place of his upbringing, by the time he got accepted to Columbia University, his primary tastes had shifted more toward hip-hop. He studied pop music and the emerging trend of hip-hop crossing over into the mainstream. He also appreciated punk-rock, among other genres. Rather than being a genre-whore, Koenig just likes a lot of bands, regardless of whatever categories critics place them in. “When you’re a music nerd,” he says, counting himself in, “you could take the whole rest of your life to dig through everything that’s made an impression on you.”

In interviews—both in this one and many others—Koenig repeatedly refers to himself as a “studio guy.” Meaning, in part, that he always viewed live shows as a presentation of the album, interspersed with some greatest hits to keep everyone happy. When done right, he loves elaborate, polished stage productions full of pomp and spectacle. He points to Jaden Smith’s recent set at Coachella, which featured a Tesla flying down from the rafters, as an example. But now, his interests are expanding.

One of several catalysts for this shift appears to be his friend, Jake Longstreth, his co-host on Time Crisis, a painter by trade and a member of Grateful Dead cover band Richard Pictures (originally called “Dick Pics,” a pun on the officially sanctioned “Dick’s Picks” archival Dead series). The two have now discussed the Grateful Dead on their podcast multiple times and Koenig has even enjoyed catching Richard Pictures live, when his schedule allows for it. (Both Jake and his brother, Dirty Projectors’ visionary David Longstreth, contributed to Vampire Weekend’s recent studio sessions.)

“When I first saw them, it was almost at the exact moment when indie music was starting to feel overly professional and sterile,” he says. “But then I saw my friend perform the music of the Dead at a tiny little art space. Beyond the music itself, it was also the vibe of seeing people perform guitar music with joy. I realized that was lacking. So, in this funny way, that experience, more than the specific music of the Dead, definitely felt influential.” “It’s undeniable that Ezra has been way more interested in the Dead and that universe (including the Jerry Garcia Band) than he was in 2008,” says Tomson, noting that the unexpected development has been gratifying for him to watch. “The ethos of jam, more than any specific signifiers, is now part of the vocabulary in a way that I find really cool and, in a weird way, a return to my own roots.”

To prepare for this tour, the band spent 14 months rehearsing. While Tomson was motivated to take drum lessons for the first time in his life, Koenig started picking up his guitar at home and practicing it more, something he never used to do. His instrument for composing new songs has always been a laptop. He defined himself as an artist and a musician, but not as a guitarist. That’s no longer the case.

“I wasn’t interested in live music when I was a kid,” he admits. “So, on a very basic level, I was always way more interested in the Dead’s studio recordings.” He cites “Uncle John’s Band” as a song that he was obsessed with and, later, around the time Vampire Weekend formed, the uniqueness of “Crazy Fingers” really grabbed his attention. And, when listening to Father of the Bride, it isn’t surprising that he studied “Crazy Fingers.” Vampire Weekend might not sound like the Grateful Dead, but—for the first time—there’s some kind of compositional branch that connects them.

Koenig’s “Studio Dead” influence isn’t a new thing. Before their very first album was released, he took notice of the Dead’s own influences. “At that point, I was interested in looking at electric guitar in slightly different ways, so I looked at a number of ‘rock’ musicians who had little moments that seemed indebted to the African guitar tradition, whether it was [The Smith’s] Johnny Marr or the Grateful Dead. There was something about it where I was like, ‘Woah! This was way before Paul Simon made Graceland.’”

Similarly, as a music scholar (he’s been known to go to a library with grad students to study lyrics), he can name-check a number of “jambands,” including Twiddle (whom he recently caught live at the Troubadour after dedicating a good portion of a podcast to a deep-dive into their song “Jamflowman”), the Disco Biscuits (whom he refers to as “Bisco”) and Widespread Panic (whom he calls by their nickname Widespread “Mother Fucking” Panic). But it’s the mention of Bone Diggers, a Bay Area band that takes Paul Simon tunes and jams them out JRAD style, that makes his eyes widen. “That kind of stuff really interests me,” he says.

Koenig’s bandmates also bring their own backgrounds to the group—it’s easy to spot the Phish fan in any crowd and, here, it’s Tomson. For today’s band rehearsal, he’s wearing a bootleg Phish shirt that repurposes the NASCAR logo to read “Curveball.” He bought it from some guy on Twitter.

For years, he’s rocked Phish shirts onstage, including some high-profile late-night television appearances, but it’s not just an ironic fashion choice: Tomson gushes that he made it to Madison Square Garden to catch one of the “Baker’s Dozen” shows in the summer of 2017 (“Lemon” night) and while he proudly recounts jamming with Phish bassist Mike Gordon—on some Grateful Dead tunes, no less—he remains a genuine front-of-house fan. “Whenever I do get to shows,” he says, “I really fucking love it.”

Meanwhile, Baio comes more from the electronic/DJ scene but has paid attention to the expanding overlap between produced electronica and live improvisational music over the past decade; he cites Four Tet’s appearance at Camp Bisco as an example of the crossover.

“I think a lot about the direction of the live show in terms of how I think about it when I DJ,” says Baio. “The idea of combining songs and transitions and things like that.”

Though Jones is new to the jamband scene, Koenig has spent some time turning him on to the Dead while Tomson has pointed him the right direction on the Phish front. “There’s so much history of guitar wanking,” says Tomson. “I really like that Brian’s sick on the guitar, but he’s true to the original spirit of Vampire Weekend.” Koenig notes that Vampire Weekend’s entire songbook is still less than the 100 tunes that Trey Anastasio had to learn for just five Fare Thee Well shows. But, with more than 60 originals in their canon, and more than a dozen carefully curated covers in their pocket, it’s getting there. Which means that the band finally has a song cache big enough to have some fun with.

In a career first, Baio says, “I don’t think we’re ever going to play the same set twice.” They’ve even worked out alternative versions of particular songs to whip out on any given night.

That’s a stark difference from their 200-show tour behind Contra during which, according to Baio, they “may have changed the setlist two or three times” over the course of a year and a half.

Koenig reveals that he’s been going onto the website setlist.fm to track changes in various artists’ setlists across entire tours (and careers). Not surprisingly, he’s been focusing his research on bands touring behind their fourth album. “More than ever, I have become very interested in who switches up their setlists,” he says. “When they do it, how they do it.”

Vampire Weekend has been described—in fact, is self-described—as “jam-adjacent.” But Koenig points out that he’d also put Bruce Springsteen and Pearl Jam in that corner. It’s an attitude, an approach and, perhaps most important, a live show for the sake of a live show, as opposed to looking at it as part of the promotional outreach of a particular album. “There is a joy in approaching the show a little bit differently every night,” he says, as his eureka moment. “It goes far beyond the definition of ‘jam.’”

“Like any kid growing up on the East Coast—and like any kid who likes rock music—I was familiar with the Grateful Dead.”

– EZRA KOENIG

It’s this specific epiphany that seems to be pushing Vampire Weekend in a certain direction more than, say, Koenig watching videos (which he has saved on his iPhone) of Dead cover bands at the Skull & Roses festival in Ventura, or having a podcast co-host that can intelligently discuss the nuanced differences between the Dead’s performances of “Eyes of the World” in 1977 versus 1990.

“We have the option now to really switch up the setlists and change up the arrangements because we are starting to feel like we have a true songbook,” he says. “Not only do we have that as an option, but it increasingly feels like the only option—for mental health.”

Koenig reflects that while touring the albums did not come without reward, he frankly just wasn’t having any fun doing it. “People would ask me: ‘How’s tour going?’ and I realized that the only metric I had to describe if the tour was going well was how enthusiastic the audience was and how many tickets we sold,” he says.

Musically, it was the same thing every night, day in and out. As long as something didn’t go horribly wrong, it was just another day at work. Muscle memory does all the heavy lifting for you; you’re not making music, you’re reciting it.

But then Koenig discovered what the jambands have always known: You don’t switch it up for the fans’ benefit; you switch it up for your own. And that makes all the difference. “So, now I’m starting to find a joy in performing that is similar to the joy I would find in the studio, where you’re trying new things and surprising yourself,” he says. “It’s perfect timing—we’ve got the songs to mix it up a bit and we’re also older and need something different.”

Back at his management’s office, Koenig glances around as if he’s about to tell a secret, then says, “If I am going to have a life in music, specifically the type of music we do—which is not mainstream pop music—it’s understood that you have to go and show people the music. If I really want to continue that, I have to find a way that I’m OK with this being a permanent part of the texture in my life. So that does become an existential question and, thankfully, I think we’re starting to find the answers.”

On the eve of a world tour that doesn’t have an end in sight, Vampire Weekend just might be discovering their best selves.

This article originally appears as the cover story in the June 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.