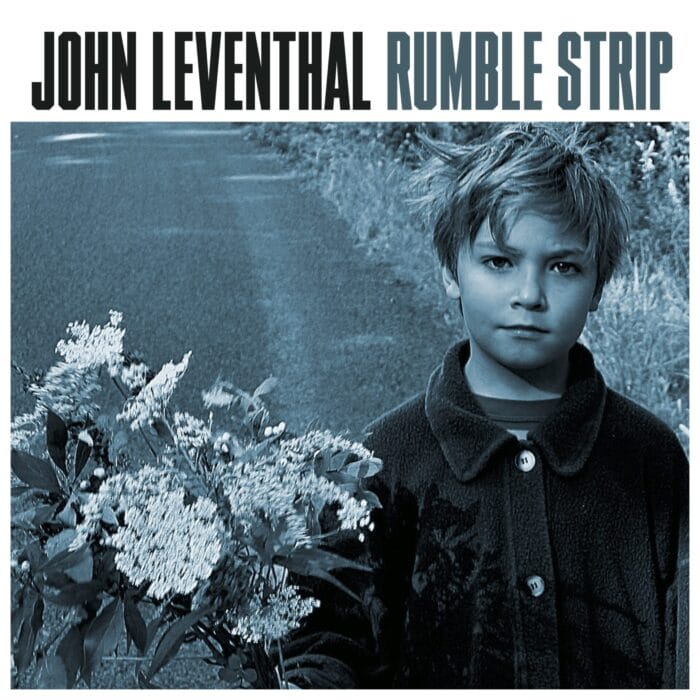

Track By Track: John Leventhal’s Long-Anticipated Solo Album ‘Rumble Strip’

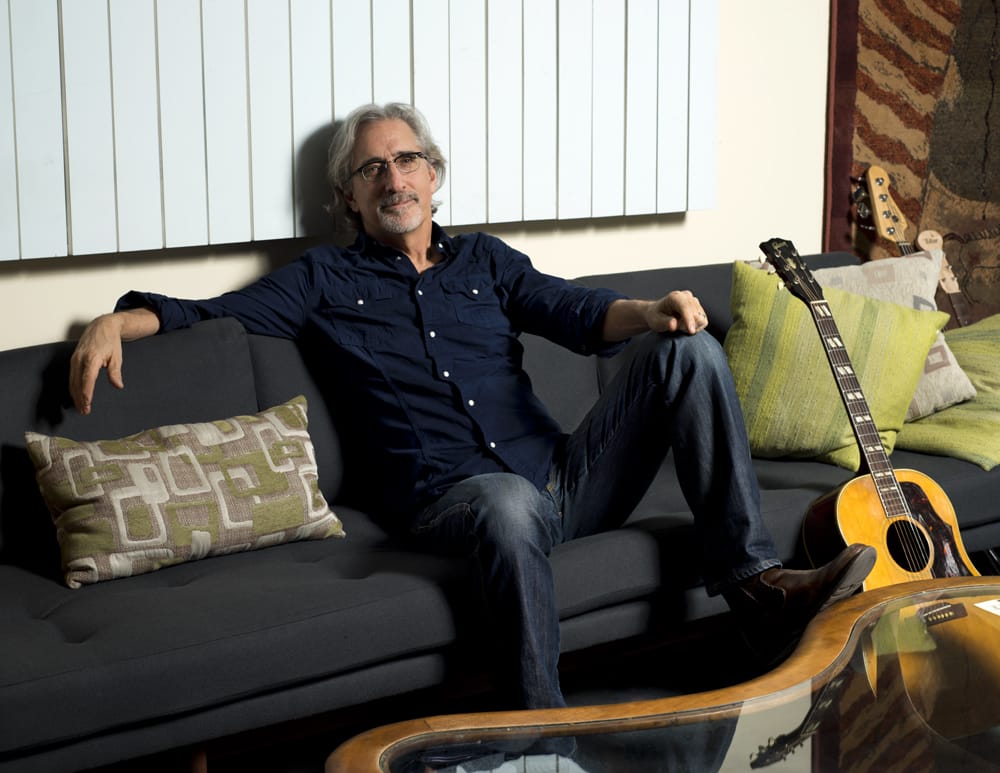

photo: Wes Bender

***

“I’m inherently a writer as well as a musician and a record producer. I write all the time and there’s a bunch of stuff that never found a home. Then, around 2015, I began asking myself: ‘What are you waiting for? Why don’t you see if you can make a recording on your own?’” John Leventhal says of the thought process that eventually led to his solo debut, Rumble Strip, more than 45 years into a vast and vibrant career.

Leventhal has produced albums for artists such as Sarah Jarosz, The Blind Boys of Alabama, Jim Lauderdale, William Bell, Shawn Colvin and his wife, Rosanne Cash. He also has written, recorded and performed with Jackson Browne, Bruce Hornsby, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Ry Cooder, Elvis Costello and many others.

“When the pandemic came, I really didn’t have an excuse,” Leventhal recalls. “Rosanne and I live in a brownstone in New York City with a recording studio that I built about eight years ago. Here we were with nowhere to go and a recording studio on the first floor. So I jettisoned all my preconceptions about what my record was going to be, and I just started writing and recording without editing myself in the hopes that some kind of direction would reveal itself.”

Rumble Strip draws on Leventhal’s wide-ranging interests and affinities. He explains, “It took me a while to find a combination of things that I had written and different approaches that made sense to me. Some things I wrote and recorded in the same day. Some things I didn’t actually compose, I just improvised. Some things I composed and arranged and made a track out of. Then I did some arrangements of symphonic composers—Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber and Bernard Herrmann.”

As for what’s next, he notes, “For me, this was like a baby step. It was a first attempt, so let’s see if I can get any traction. If it goes OK, I’ll probably keep at it and keep experimenting.”

Floyd Cramer’s Dream

This was the first thing I wrote for the album. It was about two weeks into the pandemic. Apprehensions were high, particularly here in New York City—things were kind of weird and disorienting. Then, one night, I just started playing that on the piano. It seemed like it captured an unresolved kind of thing that pleased me and I didn’t feel the need to turn it into some big statement. I liked it as it was.

I write on the piano, I write on guitar, I write on drums, I write without instruments, and that’s just something I wrote on the piano and recorded more or less in the same night.

I also have a kind of perverse nature. So while there might have been an expectation that I’d make a guitar record, I didn’t want to have that as the first thing.

JL’s Hymn, No. 2

I’ve always had a feel for a certain kind of hymn. I have a kind of standard quote I say, which is, “A good one can look sorrow straight in the eye but still leave you with some hope.” That’s appealing to me.

In the first months of the pandemic, I wrote a series of hymns. There were three of them and I gave one to Rodney Crowell. Before I focused on my record, he asked me if I had any ideas, and I sent him one that he put on his record [2021’s Triage].

Then I had these other two and I just performed them solo on a guitar. They’re very much an expression of something I’ve got, particularly as a guitar player.

Rumble Strip

On some of these things, I was trying to do what I would normally not do. When I’m writing with or for someone, I can be very analytical in wanting to make sure every aspect of the composition is dead on. But I’m glad this is Relix magazine because, full disclosure, I poured myself a whiskey and smoked one hit of weed, then I started playing a little rhythm on these percussion things and grabbed a nylon string guitar. I started playing just to see what would happen, and by the end of the next day, this song was done. I was trying to write without officially writing, just approaching it a different way.

Tullamore Blues, No. 2

This one is sort of the same thing as “Rumble Strip,” where I didn’t write it—unlike, say, “JL’s Hymn No. 2” and “Floyd Cramer’s Dream,” where I knew what they were before I started recording them. With “Rumble Strip” and “Tullamore Blues,” part of the composition was actually the recording, which was trying to get my mind to go blank, grabbing a guitar, trying to get a halfway decent sound on it and then playing until a song appeared. I wouldn’t say that I haven’t done that before, but it’s a slightly different approach. A lot of this was just breaking myself out of old habits to see if there were different ways for me to do stuff.

That’s All I Know About Arkansas

Rosanne had these lyrics, and this is sort of a classic way that she and I will write. She’ll have lyrics without music, then I’ll see them on a piece of paper and go, “What is this?”

I had no idea what it was about. She was about to tell me and I told her that I didn’t want to know.

It just so happened that I had this kind of weird little bluegrassy/West African riff or beat. So I thought, “I could write this as a duet for the two of us to try for my record.”

I liked the way it worked out and I also did something on this that I normally would never do, which is I made room for guitar solos. I don’t play a lot of guitar solos on records, but I allowed myself to play a couple of solos.

Clarinet Concerto

With the pandemic, it took a while before we were back in action, so my imagination started to wander. I’ve always loved Aaron Copland and there are certain harmonies and cadences I’ve used in arrangements that I know were inspired by him. I’ve always loved the first movement of his “Clarinet Concerto,” which was actually commissioned by Benny Goodman. It’s really elegiac and beautiful. I was listening to it one day and I thought, “I should suss this out. What’s happening here? What are the strings doing?”

Then I learned the melody and I thought it would be interesting to transpose the string part to an acoustic guitar. So that’s what I did. It’s sort of like a weird Duane Eddy track. It sounds like a simple melody, but the harmony is really moving and shifting, which is appealing to me. I’m drawn to things that sound simple but actually aren’t simple.

Inwood Hill

Inwood Hill is the only undeveloped tract of land in Manhattan. It’s an old forest, so there are 300-400 year old trees in there. It’s kind of incredible. A lot of people don’t know about it. I had written this solo guitar piece, then I tagged on this other piece and it felt like Inwood Hill to me. If you go there and listen to it, it’ll make a lot of sense.

Meteor

This is a little bluesy thing that predated the pandemic. I’ve had it in some form for 10-15 years. I had a vocal melody and I messed with some words, but it never felt appropriate for an artist I was working with. I always liked it though, so I wrote a little guitar melody and put it on the record.

If You Only Knew

Matt [Berninger] sent Rosanne these lyrics because they were talking about writing something. I think he asked if I wanted to write some music, but it was mainly going to be for her and him. This was slightly before the pandemic, and it wasn’t really that defined.

Then when the pandemic came, I started writing music to this lyric that he had sent, and I said, “Rose, let’s demo it up and send it to Matt.” So that’s what I did. It was kind of a version of what’s on the record—not that far removed.

It turned out there wasn’t really room for it on The National’s next record [Laugh Track], although, oddly enough, Rosanne ended up singing and I ended up playing on the record, but not on this song. So I asked Matt if I could put this one on my record and he said yeah.

Matt taps into some sort of Jefferson Airplane/Grateful Dead thing for me, which were bands I liked back in the day. So as I wrote it, I was thinking, “Can I kind of jam through this? Can I find a way to play some guitar in this too?”

Marion and Sam

I’m a big Bernard Herrmann fan. People often associate him with his thriller music—Psycho and the stabbing strings. But if you really listen to his compositions, he writes some of the most painfully beautiful sequences, like the love theme from Vertigo. There are a lot of others, including some incredible music from his score to Fahrenheit 451.

I was listening to the score of Psycho one day, and there was this little cue called “Marion and Sam.” It was before they go to the motel—they’re these doomed lovers. You can sense that something bad is going to happen and he writes this short, incredibly moving cue.

I love Bernard Herrmann’s harmonic sensibility. I’m always listening to music and I have a lot of curiosity—not just from rock, pop, blues, roots or country music. Particularly as I get older, I listen to a lot more orchestrated music. Rosanne and I will go to hear symphonies.

So I decided to try to understand the harmony and what the strings were doing. Then I started playing it on guitar and said, “Oh, I could play this on two guitars. That might be cool.”

Soul Op

I made a record for Stax with William Bell in 2016 [This Is Where I Live], and it was a great experience. The one thing I knew immediately was that I wasn’t going to go in there and do a bunch of Stax and Muscle Shoals clichés. I knew I had to find a way to honor all that stuff and have that live and breathe through it, but I also knew that’s not really what the record was about.

That’s always been wired into me—how do you transcend your influences while still honoring them? How do you use that as foundational information and then find your own voice?

I always had a sense that if you did too much imitating, it was a bit of a turnoff—The Beatles being an incredible template. Think of all the stuff that they inhaled, and then it came out being so original. Ry Cooder has also had a huge influence on me—more as a musical thinker or arranger than as a guitar player, although I love his guitar playing. How does he take all this material that he’s clearly deeply moved by and turn it into something deeply original? The Stones are that way as well. I think all the bands I admire have had a version of that.

When I was working with William, I had a bunch of ideas and this one never made it. I don’t think he rejected “Soul Op,” it just ended up that we didn’t really need it, so it never got to that place. I always thought it was kind of a cool idea, though. It feels like a Booker T. melody from the late ‘60s, and I liked the motion of it.

Who’s Afraid of Samuel Barber

There’s a Samuel Barber short oratorio called “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” that I’ve always loved. [The text for Barber’s 1947 score is drawn from James Agee’s “Knoxville, 1915,” a short work published in 1938 that later appeared as the preface to Agee’s novel A Death in the Family, which won the Pulitzer Prize when it was published posthumously in 1957.] In fact, a lot of these things I fell in love with when I was in college in the early ‘70s. I went to the University of Wisconsin in Madison, and I spent an inordinate amount of time in the college library where they had listening booths.

I don’t remember how I found Barber. It may have been because I liked the James Agee piece. I remember being really taken by Let Us Now Praise Famous Men [where Agee writes essays to accompany Walker Evans’ photos of tenant farmers during the Great Depression]. That led me to his novel.

The Bernard Herrmann, Copland and Barber things on the album are harkening back to what opened up my heart when I was in my 20s. At that time, I had no idea, musically, what they were. I wasn’t smart enough as a musician or arranger to understand, so they had some magic to me. It felt appropriate for me, in search of personal magic on this record, to go back to some things that represented that for me and see if I could use them in some way.

I’ve always loved that piece of music, particularly the first movement. There’s a slight Appalachian element to it, which I dug. So again, I asked myself: “Is there anything I could do with this that would be interesting to me and give me a vehicle to play some guitar?”

Even though I didn’t really want to make a guitar record, the truth is, I’m a guitar player, and when I produce records, I don’t really make a lot of room for my guitar playing, particularly soloing. So part of this was to see if I could gracefully or subtly write slightly odd, unexpected things that would give me room to play a little guitar.

Three Chord Monte

I have nothing to say about this song except that I don’t even know where it came from. It’s probably the only happy song on the record, apart from that bluesy song “Meteor.” So I felt obliged to put it on there, and I’m glad I did.

There’s also a little bit of Ry Cooder in the way I’m playing guitar. It’s not quite a homage, but I can hear Ry’s influence on that tune.

The Only Ghost

I ended up mixing Mac Rebennack’s last record [Things Happen That Way]. When I started, Mac was still alive and they were tweaking the record, so of course I was like, “Wouldn’t it be great to write a song for Mac?” That’s when my buddy Marc Cohn and I started “The Only Ghost.” It was about an old musician whose compadres have all sort of turned to dust—it’s a little bit sad. The original approach I had was a little more New Orleans than what I ended up doing.

But it ended up not happening for a lot of reasons. So I had this demo of me singing it and I thought, “Well, maybe I can handle singing this.” I’m not a great singer and part of the gauntlet for me was like, “Do you have the courage to sing a few tunes on the record?” I sing on all the records I produce, but they’re all just background parts.

I have zero illusions about my singing ability, but I listened back to the demo of this tune that was meant for Mac and I said, “You don’t sound half bad on it.” So I finished it.

Goodbye to All That

This is a solo guitar piece. At some point, the thought crossed my mind that the whole record should just be me and one acoustic guitar, though I lost interest in that pretty quickly. The title “Goodbye to All That” references that what I eventually did was an outgrowth of the original approach, after I had said, “Nah, I’m not interested in it.”

JL’s Hymn, No. 3

I got stuck on writing these kind of stately little hymns. As I mentioned, I gave one away to Rodney and I kept the other two.

When it comes to these hymns, we’re talking about the magic of music. We’re shifting frequencies around and we don’t really understand why a sequence of chords will pull at your heart and make you feel something that perhaps you can’t quite articulate. There’s this nexus of longing, hope and sadness all mixed together. Some of us are really moved by that.