Track By Track: Jack Johnson Collaborates with Blake Mills, Draws Inspiration from Jeff Tweedy on ‘Meet The Moonlight’

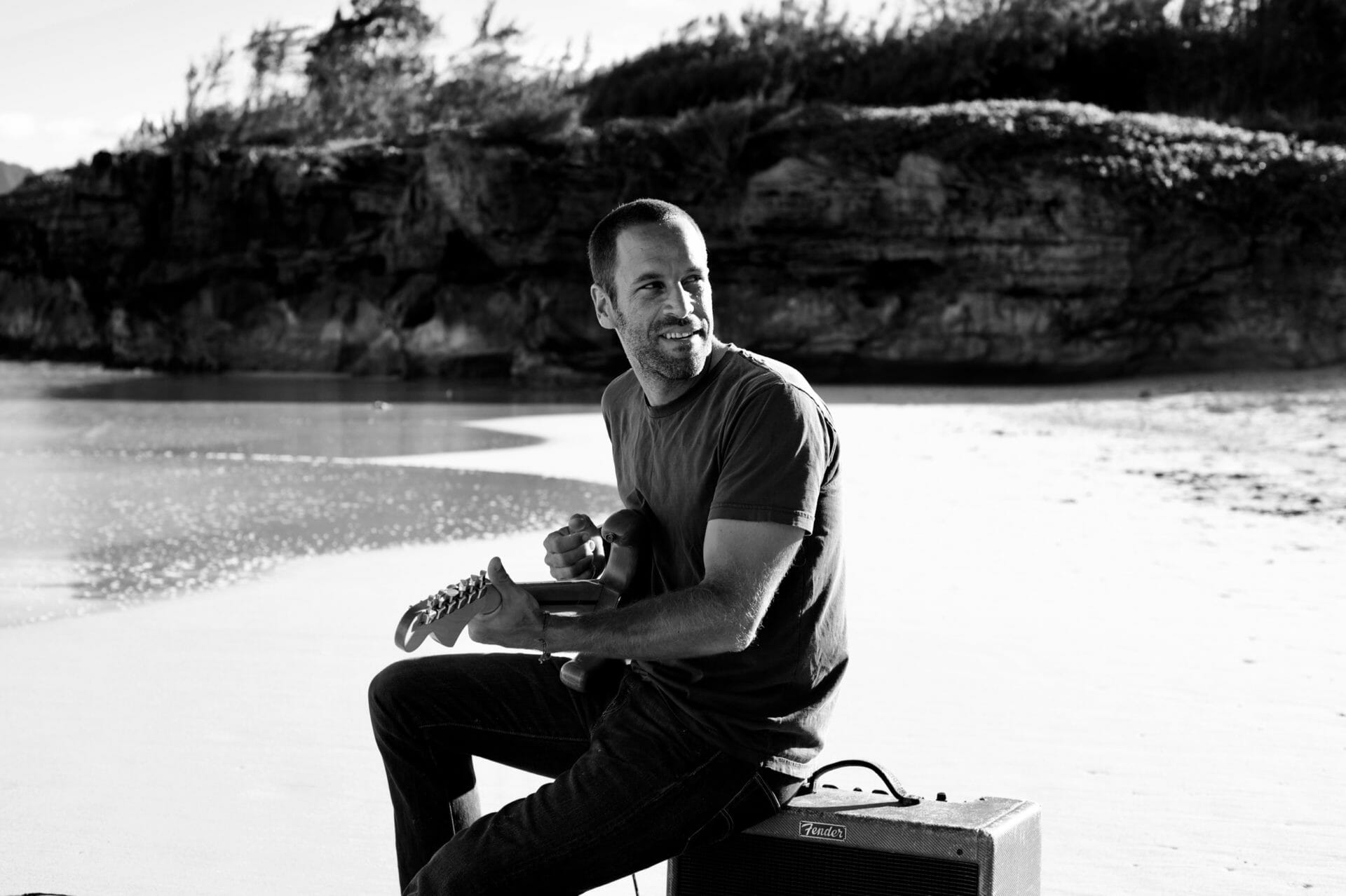

photo credit: Morgan Maassen

***

“I’m not good at sitting down and telling myself, ‘OK, I’m going to write a song. Now what is it going to be about?’ I can’t really start like that,” Jack Johnson says of the creative process that ultimately resulted in his eighth studio album, Meet the Moonlight—his first full-length release in five years. “Instead, these little sparks have to come out of nowhere. Then, once I have enough of those sparks, it feels like the right time to sit down and finish them.”

Johnson credits his wife Kim, who is also one of his longtime managers, with assisting in the process. “We’ve been together since we were 18,” he notes, “and she’s always been a little bit like my editor in certain ways, where I’ll show her all the different things and she’ll tell me the version she likes best. She also is really good at helping me get organized because she’ll see that I have all these lyrics, voice memos and four-track recordings that I’ve collected here and there. She’ll say, ‘OK, let’s get everything into one place.’ It’s kind of like making a journal because I have to bring together all these thoughts that I’ve collected over time. That’s also when I realize which ones are related and which ones aren’t—maybe one’s a verse, one’s a chorus and, while I thought they were part of separate songs, they’re actually part of the same song.”

After shaping up his demos, Johnson enlisted a new collaborator in Blake Mills. He first connected with Mills’ original music and soon came to appreciate the range of his production work, which includes Alabama Shakes, Jim James, Dawes, Laura Marling and Perfume Genius. Johnson and Mills ended up performing most of the instruments on Meet the Moonlight themselves—sharing guitar, bass and drum duties—though Johnson’s longtime bandmates appeared on a couple songs toward the end of the sessions after COVID restrictions eased.

“At first, I just wanted to sit down and play music with Blake because I love playing guitar with people who are imaginative and really approach the instrument differently,” Johnson reveals. “So we got connected and, that first time, we talked for like two hours. We discussed not only music, but also a lot of other things. We found that we shared a sense of humor, which I think is really important. Then, we decided to get together with no strings attached. So I came over from Hawaii to Sound City [in LA] for a week to play around and see what would happen. We both really enjoyed it, so we decided to make a record together.

“The way we approached almost every song was: We would sit down in the room and face each other so that we could see each other’s hands. I’d be teaching him the chord progression and we would try to capture the point when we were in that sweet zone between learning the song and going, ‘This is how we’re gonna play it.’ A lot of times, we’d be racing to see who would grab the drums or the bass because we both would have ideas. It was a lot of fun.”

Open Mind

“Open Mind” was one of the first tracks I shared with Blake. It was a rough sketch and, when Blake heard it, he said, “Let’s try to keep this one stripped down to just you and the guitar because I don’t feel like it needs much more.”

So we recorded it with just the two of us. Later, when the band came in, we played them all the tracks and tried to figure out where people felt like they had ideas. It wasn’t always their normal instruments—for instance, the bass player [Merlo Podlewski] ended up playing some percussion on that track. The piano player [Zach Gill] did play some piano that parallels my guitar line and then he also played a little melodica in the places where Blake had played these volume swells on a fretless guitar.

There’s the phrase “keep an open mind,” but Blake and I also talked about it almost like a Shel Silverstein image, where you see little people walking in through the ears or the mouth.

It’s a nice way to start the record, with a clean palette— just keep an open mind. I think it’s important to have one right now. There’s so much division and tribalism in the world. It just felt like a nice sentiment.

3AM Radio

When I was living in Santa Barbara making surf movies, sometimes I would drive down to L.A. I’d come back at 2 or 3 a.m., so I would listen to a lot of Coast to Coast with Art Bell, trying to stay awake. Blake was really into it, too. He loved the theme song for that show, which had this sort of dusty, strange synthesizer thing. There’s a sound that’s pretty low in the intro to “3AM” where I’m playing a guitar that’s plugged in through a synthesizer, and Blake is tweaking it as I’m playing it. Then we put it in reverse, and it has kind of a mystical sound to it.

This song went through a lot of different forms. We started with a little drum machine and there was almost a J.J. Cale vibe. At first, it was two guitars on top of a Casio keyboard. Then, we decided to add a little more percussion. And at some point, we turned the keyboard off, and then we just kept building the drums. I played the drums on that one with a high hat pattern and Blake added some percussion. Toward the end, Blake also added some upright bass on there, which I thought sounded cool.

Lyrically, this song is a picture of my family. A lot of times—if we’re in California on a camping trip or moving down the coast visiting relatives—we’ll try to utilize the whole day, then stay for dinner and try to do the drive at night. The kids will crash in the back of the van and my wife does her best to try to stay up, but she’ll keep dozing off. So I’m always tuning into weird 3 a.m. radio, listening to strange conversations like Coast to Coast.

So the song is a little bit of what’s going on in my life combined with the idea of hearing these different things coming through the airwaves.

Calm Down

The original version that I demoed had a groove that almost sounded like The Specials or The Skatalites. Then, I ended up doing this one version where I was just using my thumb really lightly. I decided to add a little percussion, and it’s actually this little hand drum with my wedding ring hitting against the side of it, as a side-stick kind of sound.

When we approached that song, Blake said, “Hey, bring up that old demo.” So he loaded it in and said, “Let’s just build off of this.” So it’s fun for me because, when I hear that side-stick sound, it’s just my wedding ring on the little drum. The guitar is played really quietly. There were slides on the demo, but we just decided to recut those together. We did two slides at once and it was fun tracking that. I like the way that one came out, and it’s my wife’s favorite song on the album, so that says something.

One Step Ahead

I had a few different demos of that one. I had some acoustic ones and some where I played a full drum set. That was the first song we worked on at Sound City. We tried something where we did this drum track and we were both next to each other. He played mostly the kick and the snare stuff, while I was doing a hand drum pattern and it was all tracked at once. Then, we put the bass on and it kept getting bigger and bigger.

Until then, we had talked about having an album that felt like really good demos. We were going to see if the songs wanted more, but we wanted it to feel a little homemade and pretty stripped down. The original version of “One Step Ahead” ended up becoming pretty big, though. It almost sounded like Peter Gabriel to me on our first pass at it.

Then, when Blake came to Hawaii, we decided to try a different version. We liked the bassline but took everything out except for the bass and recut everything around that. It felt really good to us but, when we played both the bigger and smaller versions for my friends, everybody liked the earlier one—they would say, “It’s banging. It sounds really energetic.” I kept trying to explain what the album was going to sound like but we couldn’t get away from the fact that most people who heard it liked the big[1]sounding one.

Then we had the drummer in my band [Adam Topol] do a pass. So we did a hybrid of the Sound City drums plus my drummer.

There are still some of the guitars from Sound City in there, as well as some ukulele from Hawaii. So it ended up being a mash-up of all the different ideas. That song went through the most iterations of any on the album. It was a lot of fun to hear all the different versions and let it be one of the quietest songs for a minute and then build it back up.

Meet the Moonlight

This was the one where Blake helped to push me out of my comfort zone. I had a version of it, like a demo, and the first time we played it together, we sat down and he said, “This is one of my favorites. I’m excited to try this one together.”

When we started playing it, I went to this one lick in the Lydian scale that sort of changes up and I played the line wrong, at least in my mind. I corrected it the next time, and I played the line how I had written it.

Then Blake said, “Wait, play it like you did the last time. That sounded cool.” I told him: “Oh, I just hit the wrong note.” He was like, “I know but it sounded better like that. Try it again.”

I had it in my head that the first time I had done it was a mistake, and he had it in his head that it sounded better that way. So we argued about that song for like the whole recording. We eventually did another version and, by that time, I was willing to admit it might be better that way, so I did it like that.

It was interesting. Most of the people I’ve worked with would do their best to push an idea on me and, if I fought it for a day, they’d be like, “OK, you win, whatever.” But Blake stuck with it, to the point where it became our ongoing joke. In the end, I added this nylon string part that was kind of more like my original idea. I really liked the way they blended and I think Blake enjoyed it even more once he heard that part on there, too. But it was a process.

Then there’s the outro. I can’t imagine it being any shorter now, but when we first played it, I thought it would have a fade out or we might edit it. But as were finishing up and starting to think about the sequencing, Blake was really adamant: “No, you’ve got to leave the whole thing. It’s beautiful.”

At one point, when we were mixing it, I looked over at the engineer who was helping us and it looked like he was dozing off because it’s drifty. So a big part of the reason that I put “Don’t Look Now” next on the record is because the first line is “Come on, wake up.” So, in case this part was putting you to sleep, there is a line about waking up right after. [Laughs.]

Don’t Look Now

“Don’t Look Now” came in at the end. We were going into the mixing, and we had done sketches of four or five other songs that didn’t make the album, but we hadn’t recorded a version of this one yet.

So we went back to L.A., I got the band together and we jumped into the room. The bass player played a keyboard bass that was run through a fuzz pedal, which was a fun way to do it. Blake played a cool[1]sounding fretless guitar. I love the counter melodies that he added onto it. It kind of brought the song a new life that I hadn’t even expected with those parts. So we tracked that one live and then I did the voice after.

Costume Party

Blake and I were having a beer and listening to some of the tracks when I showed him this trick with “Dazed to Confused” and its descending bassline. If you keep taking a sip of beer and then blow into the bottle, the pitch gets a little lower. So you can do this thing where you can sing the song and sip a beer while doing that whole bassline.

I was joking around with the bottles, but Blake was like, “Let’s figure out a way to get that on there.” So that’s how the beer bottles ended up on “Costume Party.”

Blake was really good at noticing things that I might be joking about and putting them on there. Like if I was on the drum kit, and did a big fill , sometimes he would leave it in and say, “That’s the best part.”

There were three versions of “Costume Party.” The first one was a little more of a rock song, almost like Weezer. We recorded it when we were trying to figure out what direction the album would go. Blake played a fuzzed-out bass and I played an electric guitar and the drums .

The second one was really percussive. It almost had a Brazilian vibe.

Then, the last one we referred to as the after-party. I liked some of the upbeat ones, but Blake’s suggestion was that the lyrics worked a lot better when it was sort of the drunken after-party, where they’re delivered a little slower and seem a little more cynical. So that was the one we went with and the bottles were a fun thing to do. We had the tuner right there and I had to pour a little out or add a little to figure out where the right notes were.

I Tend to Digress

“I Tend to Digress” was the first song I had in this batch. It was written on the last tour actually. Zach Gill had this little looper pedal, and we would do all kinds of stuff with it. One morning, we had a day off and we were messing around in his room with this thing and he was doing some throat singing. Then, he had a drum loop going and said, “You should write something in here.” So I had this stream of consciousness where I wrote everything down that came to my mind and laid it on there.

On this day off, the place they put us was a funny spot right at the last hole of a golf course. Neither of us really plays golf or anything, but we were sitting out front, drinking coffee and watching people come by. You could hear their conversations. They would be talking about how they really shanked that one or whatever. Then, this one guy was like, “Well, I feel like we got our money’s worth, boys.” It’s a pretty common thing to say but, for some reason, it just struck me because there was this bird in this tree and it was singing this beautiful song. And so the dichotomy of the two things— thinking of things in terms of their financial worth and this beautiful birdsong—just jumped in my head. So I wrote about birds singing songs about getting their money’s worth and some other obscure ideas.

I wrote all those words and, a couple years later, I remember thinking, “There was something to that. It was kind of fun.” So I called Zach and said, “Can you find that track and send it to me?” I just put it to an acoustic guitar, did a quick pass of it live and Blake added a little flanged[1]out electric guitar behind it. Then it was done.

Windblown Eyes

I wrote this one after reading the Jeff Tweedy book, How to Write One Song and thinking about some of the things that he talked about. It feels strange to share that I was reading a songwriting book and utilizing it—you like to try to keep the mystery—but Jeff Tweedy is a big enough influence on me musically that it’s kind of fun to be able to say that. His book definitely lit a spark in me. I liked a lot of the things he said about songwriting and how it’s a craft worth working at. That helped me sit down, take a few lines that had been floating around over the previous couple days and finish the song.

When I was writing papers in high school or college, I would always come up with my thesis way ahead of time. I wouldn’t be stressed since I knew exactly what I wanted to write about, but I would always be the guy who would stay up all night before the paper was due because I needed a deadline to finish it. I’m the same way with music—if I don’t say, “OK, I’m gonna make an album,” then I’ll never finish the songs. They remain being one verse, one chorus—the original spark. Usually, the next two verses take a little work for me. I have to go, “What am I trying to say? What’s happening here?” So, the Jeff Tweedy book was cool because reading it helped me go, “I’m gonna give this a shot to see if this works.”

It was cool making that one in the studio, too, because we had a little bit of steel drum and there’s this part where everything drops out except for the bass, the steel drum and the voice. Again, that was due to some of Blake’s cool production ideas. They brought the song to a place where I didn’t really expect it to go, which was nice.

Any Wonder

“Any Wonder” is a song I had around for a long time, but I hadn’t finished. It almost made it on the last three records. Then, I took the lyrics from another song I had been working on that felt a little more powerful and I tried them on the song. Blake has a songwriting credit with me because I had a lot of the song kind of already hashed out, but we sat down toward the end and he helped me choose which lyrics we liked the best and what direction we should go in.

That’s kind of how he’d work in general. A lot of times, he would tell me which lines he felt were strongest or ask me: “What do you mean by that?” With “Any Wonder,” he told me that he thought I wasn’t finished with the song because the chorus jumped up so much and felt too dramatic. He said, “Let’s transpose it so the chorus is still in D and you can sing it easier. Then, you can go up at the end.” That was a cool product of his musical know-how, and it helped me figure out how we would get the chorus in a different key altogether.

At one point, I thought “Meet the Moonlight” would be the last song but this one felt kind of raw and it was a nice thought to go out on. One of my wife’s uncles, who just passed away, was like an uncle to me. I’ve known him since I was 18. The album is dedicated to him: Uncle Darryl.

Lyrically, I was thinking back to losing my father, which was years ago, but he was a huge part of my life and a big influence on me. Sometimes, I still feel those thoughts and feelings of loss going through my head—and then I lost an uncle. So that was fresh on my mind, and it was a nice way to end the album. It was a nice sendoff: “You can always come back home if you can hear me.”