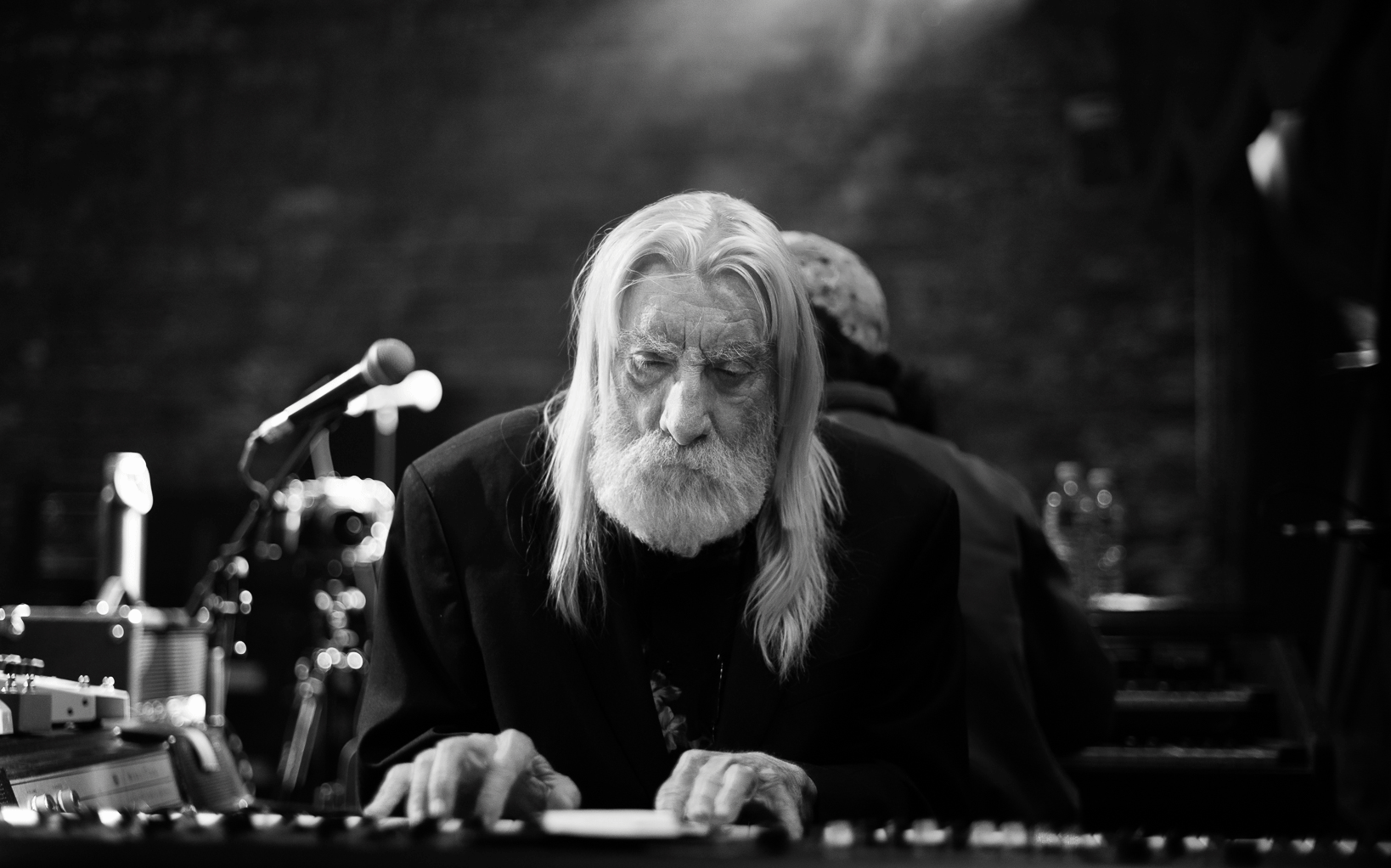

Tom Constanten: The Ongoing Interstellar Journeys of a Travel Agent

Photo: Marc Millman

***

“I can’t believe my great good fortune,” Tom “TC” Constanten says, as he takes a moment to contemplate the labyrinthine personal path that has allowed him to pursue a lifelong passion for music in its many forms. “It’s like a stream that flows downriver and becomes a creek, then a river. It grows in ways you can’t always predict. But in my case, it’s taken me a lot of incredibly interesting places, including Brooklyn this past January with Relix.”

Long before joining Taper’s Choice and Mikaela Davis at Brooklyn Bowl to celebrate Relix’s 50th anniversary, Constanten was a precocious Las Vegas high school student who gained local recognition as a composer of classical music. From there, it was on to UC Berkeley, where he became roommates with fellow avant garde enthusiast Phil Lesh. He would go on to study in Europe, enter the Air Force and, eventually, reunite with Lesh and their mutual friend Jerry Garcia, contributing keyboards to two Grateful Dead studio records (Anthem of the Sun, Aoxomoxoa) and touring with the group from 1968 into 1970.

Over the successive decades, he continued to bridge the classical and rock realms, while often seeking out experimental climes. He reflects, “Part of the ‘60s outlook was about connecting apparently disparate worlds with interplanetary travel. We would hail new experiences. For me, the attitude was, ‘Let’s get it on!’”

He’s embarked on recent excursions with Dose Hermanos— his all improvisational duo with Bob Bralove—as well as Live Dead & Brothers and Live Dead ‘69.

In August 2024, the 80-year old musician announced that he would step away from active touring. However, this does not mean his creative ventures have come to a close. He clarifies, “What I’m cutting back on is those situations where every day consists of driving 200 miles, checking into a hotel, going to the gig, going back to the hotel and repeating this for two weeks. I’m still up for a one-off, here and there. The party goes on…”

The front page of your website features an image of you in a White Sox uniform. Since the 2025 MLB season is just getting underway, it seems fitting to ask about the origins of that photo.

It was Grateful Dead Night, and they had me to throw out the first pitch. It happened twice, in 2016 and then 2017. The first time, my catcher— who was actually a pitcher— was Chris Sale. As he and I were walking back to the dugout, we were talking about Vegas back when I lived there. It was kind of funny. Then the second time, it was a minor league catcher who was just brought up. He handed me the ball and said, “My parents love your band.”

Can you talk about the nature of your baseball fandom?

I grew up in the New York City area in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, which was a golden age of baseball there. My dad took me to see the Giants, Dodgers and Yankees. The f irst game I went to see, the Giants first baseman, No. 25, Whitey Lockman, waved to me and said, “Hi, Whitey,” because I was a toehead. From that moment forward, I was a Giants fan. It is a remarkable coincidence that they moved to San Francisco and so did I.

To your mind, is there a connection between music and baseball?

I think you’re onto something. Look at DeadBase and all these archivists who are probably closet baseball fans applying the statistical approach to Grateful Dead shows—people can take it to no end of detail in both settings.

I’ve got some books with statistics from the ‘73 World Series. I went to the games in Oakland. These books had statistics for each batter, with percentage ground outs, strikeouts and fly outs. They also had a percentages for pitchers of strikes thrown per count.

I also have a couple of scorecards from the 1950s when baseball was so stable that the lineups were printed in the scorecard. The entire lineups were there, with the obvious exception of No. 9 at the bottom because the pitcher varied. That wasn’t true anymore by the 1970s, let alone today.

Did Las Vegas have a AAA team when you moved there?

Not yet. My dad Constanten, my stepfather, was in food service. He was a supervisor at the Copacabana in New York. In 1953, he got a job offer for the Sands Hotel at the Copa Room and he moved us there the next year when I was 10. There was baseball in Vegas, but it was sporadic. There were a couple of Cactus League games there that I got to see, including one in ‘56 with the Giants and the Cleveland team. Willie Mays was there, of course, and I had seen him in his rookie year in ‘51.

That period from the late ‘50s into the early ‘60s is considered peak Vegas by a lot of folks.

Yes, the Rat Pack era. Especially with my dad working at The Sands, it blows my mind that I would run into the people I did. My dad brought me into work one afternoon and I met Jimmy Durante. I saw Liberace play in ‘57. Then, in ‘61, Tony Morelli—who conducted the orchestra at the Copa Room, which is where Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin played—had a concert with four “Musicians of the Future,” one of which was me.

During a rehearsal for the Tony Morelli piece, I met Jerry Lewis and Lou Brown, his music director. Knowing what I know now, I should have cultivated a relationship with Lou Brown, he could have gotten me gigs. He put together a group called Gary Lewis & the Playboys.

Joe Guercio was another one. After the Morelli concert, he walked up to me and said, “Hey, come to my show. I’ll comp you a backstage pass.” I didn’t take him up on the offer, as I could be incredibly stupid and sightless. I missed about 500 chances to get a backstage pass to his show. Then he was the music director for Elvis Presley, so that keeps me modest.

Of course, in ‘61, I met Phil Lesh and Jerry Garcia, and we know where that led.

Thinking back to the early ‘60s, which is the era Robert Hunter describes in The Silver Snarling Trumpet and Dennis McNally examines in his new book (The Last Great Dream), how did you view the transition from beats to hippies?

Well, two things about that. First, beat and hippie are two generalized terms that from my viewpoint, hardly mean anything. In ‘61-‘62, when I was in the thick of that, there was a transition and you couldn’t really tell where the line was in which one changed to the other. In fact, the first time I heard the term hippie, it was a put-down for somebody who was affecting the trappings of beat hipness and wasn’t making it.

So things were in flux, and that’s part of what made it so attractive to us. I mean, when you’re doing something that hasn’t been done before, there’s nobody to tell you how to do it. That’s both a plus and minus.

It also speaks to the early days of the Grateful Dead when Phil was just starting out on bass and the whole band was acclimating to electric music.

We were exploring new realms and new passages, and we really didn’t know where it would go. So much has been revealed since then that was not revealed to us at the time. It was like, “I don’t know how I got here, but I can’t turn back.” You keep moving along and you see where it leads. It was all quite unexpected. Jerry Garcia expressed his surprise many times that anybody should be interested in this “thing we do on stage.” [Laughs.]

During your time with the Dead, did you have any inkling as to the nature and scope of the devotion to follow?

Nobody had any idea. It was hard to wrap your brain around, even if you were involved in it. We were just making everything up as we went along. Time was moving faster. There was a different perception of things going by. I noticed right away that “on the bus” was the expression that they used for it. You felt you were going somewhere you didn’t know, but what’s the Yogi Berra quote, “If you don’t know where you are going, you’ll end up someplace else.” That also might have been said by Ken Kesey. [Laughs.]

Advancing your circuitous journey to the present, what were your impressions of being on stage with Taper’s Choice and Mikaela Davis back in January for “Mountains of the Moon” and “Dark Star?”

I loved what Zach [Tenorio Miller] did with those arrangements. It was like rock-and-roll done by Beethoven. It was fascinating to listen to them.

Mikaela is a treasure. I saw her backstage rehearsing with Mike Gordon, and the commitment and the expertise that she brings is wonderful to behold.

Zach has performed in a variety of settings over the years, which mirrors your own path, to a degree. You’ve been drawn to so many sounds and styles going back to your youth and then you’ve incorporated them into your musical lexicon.

Looking back on my early musical passions, it gave me this great background. I’ve described what I do as I practice Chopin and Rachmaninoff, but I pay the bills with rock-and-roll. You go with what you’ve got, wherever the situation is.

I had this discussion with Melvin Seals a couple of years ago, and he says he doesn’t practice the rock material. He practices improvisations of orchestral sounds. I could see that in his playing. He verges in that direction. There’s a whole bunch of creativity there.

A memorable Grateful Dead version of “Mountains of the Moon” took place on Playboy after Dark in 1969 when the crew dosed nearly everyone. What do you remember of that?

Somehow they missed me. I mean, they got me some other times, but they missed me that time. I remember that the harpsichord was very classy and one of the very few real things on the show. I was seated in front of what looked like a highfalutin Hi-Fi set, but it was a facade. During a break, I was wandering the set and I looked at the library—they must have bought the books by the yard at a garage sale. I think the most interesting one was Miss Pickerell Goes to Mars. The others weren’t even worth stealing. Also on the show were Sid Caeser and Sidney Omarr, the astrologer. I understand we were one of the few bands to actually play. The other bands would lip sync to the 45. I saw Iron Butterfly on one and I later toured with them, so I should have asked them about it. I’d love to see the whole show sometime.

Something else I’d like to see is the episode of Guiding Light where I had a walk-on. This was in the late ‘90s when I worked with a musician [Joe Gallant] who was working on the set. He suggested that they bring me on. In my scene, I walked into a restaurant and somehow get spotted. Somebody asked, “Are you TC?” And I said, “I’m the only one I know of.” Then I sat down in the background, being careful not to eat too much of the salad because if we did more than one take that could be embarrassing.

Briefly back to that Playboy After Dark performance: It’s a rare opportunity to hear you on harpsichord in a live environment where it otherwise would be lost into the band’s sound.

You’ve touched on a sensitive point there. With the amplification of the instruments, keyboards just could not compete with the electric guitars. With four Jerry Garcia Twin Reverbs turned up to 10, even though they had a second Leslie speaker for the Hammond organ, it was still drowned. It was like my dynamic range consisted of double forte, triple forte and anything below that was inaudible.

Dr. John wrote about Jimi Hendrix in this context. Apparently, Hendrix was so loud that when they were on the same bill, Dr. John would flee the premises before Hendrix took the stage.

I totally get where he is coming from. The electric guitar sound of the time needed to get up to a certain level for that sort of violin continuity in the things that Jimi Hendrix did. If you couldn’t do that, then the rock thing couldn’t happen. You were back in the land of Charlie Christian and Wes Montgomery, which was a very different thing.

The evolving nature of rock amplification during that era is significant and often overlooked.

When Pigpen would describe Owsley’s system, he said, “It works 100% well 50% of the time, but there are times I’d settle for one that works 50% well 100% of the time.”

Thinking about the Grateful Dead songbook from that period, can you talk about “Caution?” That tune has sort of fallen by the wayside over the years.

Well, it came out of “Alligator,” and I couldn’t even tell you where the boundary was. We’d dive into this space and somehow we knew what to do. There were certain landmarks in it, like where Garcia would play a particular guitar chord loudly and then it moved on in a certain direction. It was sort of like we didn’t know what we were doing, but we didn’t let that bother us.

Moving to Phil, after he passed, you mentioned he was like the big brother you never had.

That’s exactly correct. He was four years and four days my senior, and he sort of helped me learn how to walk, so to say, metaphorically.

Although it seems like your musical interests were on par.

We were both rather fully fledged by then, although you can add that indefinable element of teenage omniscience you feel like you have. Las Vegas was a rosin-scented Oz when I lived there, with a lot of top-notch musicians from New York and Europe. I took music lessons from Dr. Chase at the university and we would do things like play a Mozart concerto with two pianos. Then the next week, we’d be talking about 12-tone technique. I was diving in with both feet.

This past fall, as you were sharing memories of Phil, my favorite was the story where he had gone to bed and you put on Mahler’s Third Symphony. Then when he came out of the bedroom, you said, “I’m sorry, I’ll turn it down,” and he responded, “No, turn it up!”

Well, that story is a perfect encapsulation of how he was. He was omnivoraciously interested in all kinds of music. From jazz, we wound up getting the Coltrane records on Impulse!, like Africa/Brass, A Love Supreme and Ascension.

I knew a drummer in Las Vegas who lived just a block off Fremont Street and his room became party city. So whenever he wanted to clear the room of everybody but his friends, he would put on Ascension and, suddenly, they had somewhere else to be. So 10 minutes later, it’d be just him and his friends, and we’d listen to it until the end. That’s the music that was turning me on, those Bob Thiele productions for Impulse!.

That reminds me of seeing the Aquarium Rescue Unit when Bruce Hampton would sometimes clear the room with atonal music so that he could play to the audience who remained. Oteil Burbridge, who’s joined you on occasion, was in ARU and also the latter-day Allman Brothers Band. You’ve performed some ABB music in recent years, so I’m curious if you ever saw the group with Duane Allman?

I saw them once at the Beacon Theatre in New York later on, but I missed them way back then. I pretty much was confined to seeing the bands that were on the same bill as us, which was a pretty hefty amount of them. I remember once, in Massachusetts and Worcester, we shared the bill with Roland Kirk and, oh my, was that interesting. That was also one of the times that the quippies—the equipment crew—got to me with a nice hefty dose and it became even more interesting.

They had these little vials—I think they were Murine vials— and they would squeeze it onto your skin or they would put it on the lip of a beer can that was closed, and you’d take the pop top off thinking you were being careful. You’d want to be careful in a very different way in about half an hour.

That was during the period of time when you were abstaining?

Yes, I was trying to follow William Burroughs’ advice and make it without any chemical corn.

At either of those shows was there any cross-pollination between the two groups?

I hung out with his bass player backstage, and that was fun. He was a wonderful gentleman and a great musician.

It brings to mind Miles Davis opening for the Grateful Dead at the Fillmore West, which reportedly rattled the Dead a bit.

Apparently Phil said, “Maybe we should open for him.”

You recently described sort of lucking your way into a Miles show with Phil when you were underage.

Yes, Phil took me to see Miles at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco. It turned out that Tony Williams was on drums and he was also underage. As a result, there was no alcohol that night, which meant they let me in.

Thinking again of interesting Grateful Dead bills during your time with the group, what do you recall of the night with The Velvet Underground and The Fugs?

That was in Pittsburgh [at the Stanley Theatre on 2/7/69]. Paul Krassner was the emcee and, gosh, that’s one of the shows I’d love to experience again. That and one of the nights in Boston with the Bonzo Dog Band [at the Boston Tea Party on 10/2-4/69]. They were pretty zany.

Returning to the amplification issue, that’s part of the reason you decided to move on from the Dead?

Well, I also had this opportunity to do Tarot. I knew it would be a smaller pond, but I’d get to be a bigger fish. Again, in 1970, nobody knew what would become of the Grateful Dead. It’s become a phenomenon since then that nobody foresaw.

I’m not sure if you’re aware, but there’s a corner of the internet that’s really obsessed with Tarot.

Well, that’s gratifying and totally justifiable. It was quite an amazing show. Joe McCord, who put it together, was quite an amazing person, too. He has this story about when he performed for Charlie Chaplin. He studied with Étienne Decroux in France. He put together this amazing show where the characters were from the tarot cards. There were no words.

He brought me along to write music for it, and we had two runs in New York City—first at the Chelsea Theater Center in the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and then in Manhattan at the Circle in the Square on Bleecker Street. The deal was we needed to earn $9,000 a week. That was 1970 dollars—now, you’d need to earn that in a day or maybe even an hour. The box office doubled every week from $2,000 to $4,000 to $8,000, but it was below the line. If it had continued, who knows where it might’ve led. Maybe we could have got to my suggested dream that we’d throw the tarot cards every night and do what they said.

There were a lot of amazing musicians. Paul Dresher, who’s since gone on to fame with original instrument building, was our lead guitarist. Chicken Hirsh [of Country Joe and the Fish] was our drummer, and it was quite an experience.

What followed from there?

Michael Butler [producer of Hair] saw Tarot and asked me to do the music for his next show, which was supposed to be a rock musical version of Frankenstein. This was like 1971, and he moved me to LA. I made $500 a week, which is the most money I ever made for not doing a stitch of work. He went through five writers, none of whom came up with a script.

I was living in West Holly wood and I had a lot of spare time, so I was looking for work. An old friend got me in touch with Jeremy Kagan, who was doing his master’s thesis at the American Film Institute. I did a film score for him [The Love Song of Charles Faberman].

I did a bunch of auditions, but I got really tired about hearing about my “very good but…” They would say, “You’re very good, but what we want is a chick singer who plays the trumpet.”

At that point, Michael Butler decided to run for the Senate in Illinois, and the Frankenstein project died down. I moved back to the Bay Area and did a two-year run at the U.S. Post Office. I was a clerk until Lukas Foss came to my rescue. He got a position at the State University of New York at Buffalo. They had an avant-garde music thing going—the Center for Creative and Performing Arts. He invited me to become a creative associate. The advisors were Lukas Foss and Morton Feldman, the associate of John Cage and, oh my, was that interesting.

During your stint in the Post Office, were you playing or composing?

That was the beginning of the ragtime resurgence. I wrote a couple of ragtime pieces I wound up playing at ragtime festivals, which was kind of fun. There was a guy there, a clarinetist, who said his teacher toured with the John Philip Sousa band, and they did the same set every night, wherever they were, including encores. I told him: “Geez, you might as well put on a suit and tie and get a real job.”

This seems like the proper moment to jump ahead and discuss Dose Hermanos, where you and Bob Bralove take the opposite approach.

Yes, the goal has been to dive in and get as close as we can to 100% improvisation. When we started, it was a very pleasant surprise that were able to get away with it at all. It’s an intuitive thing and a very seat of your pants, spur of the moment decision-making sort of thing. It initially reminded me of taking a deep breath, so to say, in my solo set before I would play “Dark Star.”

Apropos of your name, the two of you initially dosed before every performance?

Our first two dozen shows. We discovered all sorts of things. There were places that we could return to, musically speaking, like clearings in the forest or the view of a waterfall. Now, we can come back and they’ll be there.

Bob mentioned to me that some of your early rehearsals involved psychedelics that had been left behind by Ken Kesey in the walls at Club Front [the Dead’s longtime rehearsal space] and then were rediscovered by a roadie.

It was crystal mescaline. One of the equipment crew said, “It should be about here.” Then he punched a hole in the wall, brought out this bottle and said, “Oh, there it is. You want some?”

We discovered that you had to mix them up. If we took the same thing a couple of days in a row, it didn’t work. So we’d do mescaline, LSD and psilocybin. That way we kept it afloat.

Although you’re not touring these days, I’ve heard that the two of you have continued to record.

Bob flew to New Mexico a couple of times in the past year. We’ve got a bunch of stuff in the can. We’re going back and forth about how to best present it.

This time we’ve opened the doors to electronic transference and manipulation. There are a couple of vocals, with Bob in his inimitable Tibetan-voice style and me with kind of a voiceover that I don’t quite know how to characterize—it’s a cross between Lord Buckley and Monty Python, perhaps.

In creating new music at this point, to what extent will you work from a name or a shared concept? Or does it all come together on the fly?

From A to Z, every possibility occurs. Sometimes we’ll take a name or a concept and go with that for a given piece. Although on occasion—even when we’ve done that—the piece winds up having a different name. Many other times, the name comes after we play because you have to draw the entire dragon before you can see that it’s a dragon.

Sometimes we’ll both be applying a certain template— conceptual or musical—and the other one will interpret it using a different template. So it’s like an Abbott Costello routine that works. We have the ability to misunderstand each other correctly.

In the live setting, you’ve sometimes asked the audiences for prompts.

Yes, for an encore. In the same spirit as Terry Riley’s titles for his compositions, I’d ask the audience for three things— something generic, something ideal and something noble. Then we’d put those together and play that. “Frozen Hippopotamus Waltz” was one of them.

We also would work from visual cues. I remember we did an outdoor festival near Mount Shasta and we used the line of the silhouette of the mountains to inform our melodies—so we were playing the mountains. Or it could be birds on telephone wires, where the wires are the five lines of a musical staff and the birds are the notes. The metaphors are all over the place and we touch upon them as freely as we can.

There was also a time when you were both controlling video with your keyboards. Can you describe how that impacted the music?

The MIDI output was going to video and Bob set up about a dozen different video patches. It’s interesting being at the place where you don’t know whether you’re playing what you’re hearing or what you’re seeing.

We used [Eadweard] Muybridge, the guy who did those time-lapses of a galloping horse, dancers and other stuff, where if you played a couple of notes, you’d get them to move in a certain way. It was a motif defined by what you were seeing rather than what you were hearing, which was an interesting intersection.

Over the years, as you’ve become more familiar with one another and shared so many musical spaces, does it become more challenging to improvise together?

Well, you wake up and it’s a new day. Every time you play that second note, you create expectations. Then when you have expectations, you can do one of three things—you can frustrate them, meet them or exceed them. So whichever one of those you choose is a spur of the moment decision.

But yes, it can be a bit of a challenge because when you’re exploring an enchanted forest, you find certain clearings that are so vivid and so iconic that they’re easy to go back to. That can cause you to lose a bit of your edge because you can get relaxed and complacent. It’s like when you’re playing a tune, you get past the iffy bridge and then you’re on to the chorus where you say, “OK, I know what I’m doing now.” It’s like your feet are back on the ground. We like our feet to be firmly planted in the air.