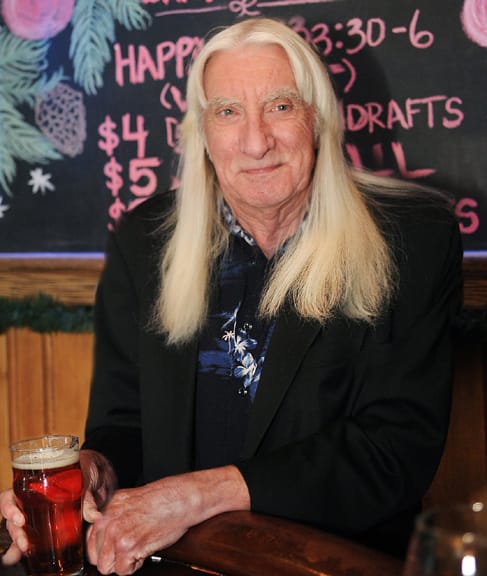

Tom Constanten: Dark Stars, Dead Bolts and Dose Hermanos

“I was surrounded by music from a young age,” offers Tom “TC” Constanten, as he traces the origins of the wide-ranging creative expressions that first yielded public recognition in 1961, when the Las Vegas Sun took note of a piece the 17 year old had written for a local youth orchestra. “I lived in Bergen County, N.J., until I was 10. We had the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic—any number of amazing concert artists would come through on tour. Dad Constanten worked at the Copacabana, and he took me in one day where I met Jimmy Durante, Jerry Lewis and Lou Brown—Jerry Lewis’ music director who put together the group Gary Lewis & the Playboys. Then we moved to Las Vegas during a golden age of music. I was a backstage urchin at the Copa Room at the Sands Hotel. It was a wondrous buffet for me.”

Constanten has continued to feast on a smorgasbord of sounds throughout his active career as a composer, keyboardist and academic artist-in-residence. He joined the Grateful Dead in the studio for Anthem of the Sun and Aoxomoxoa, and toured with the group from late 1968 through early 1970, including the performances captured on Live/Dead. In addition to his prolific classical output, Constanten also has appeared in many other settings, including steady gigs with Jefferson Starship, Henry Kaiser, Jazz Is Dead, Terrapin Flyer and the Live Dead ‘69 ensemble. In the early ‘90s, he partnered with Dead lyricist Robert Hunter for a series of performances—sometimes they would perform solo sets, and on other occasions, Hunter would read his poetry while backed by Constanten (with Michael McClure and Ray Manzarek teaming up as openers).

Earlier this year Constanten and Bob Bralove released Persistence of Memory, their latest record as Dose Hermanos. Their ongoing collaboration will be the subject of a later piece, with the following conversation touching on the period that preceded Constanten’s partnership with Bralove.

Some folks may be surprised to learn that although you received a scholarship to UC Berkeley, it was for science, not music.

My parents got me piano lessons when I was about eight years old, but I was gorging myself on everything during those years. I was into astronomy—I had a modest-sized telescope, and I would make drawings of the moon and the planets. I was into languages—I ultimately wound up with five years of Latin, which made learning Italian real easy. I was also studying German because interesting books and articles about space travel and rocketry were in German. So my interests were all over the place.

I rebelled against piano instruction as was customary, except what saved me is I would practice something else. I heard piano music that I wanted to play, and I would practice that instead. So at least my hands were on the keyboard. Then I began writing compositions by the time I was 15 or 16.

Shortly after that, I became interested in European and American avant-garde music. By the time I went to UC Berkeley and met Phil Lesh and Jerry Garcia, I was highly into it.

How would you characterize the distinctions between American and European avant-garde music at that time?

The European avant-garde was getting more and more objectified. It got so where it took a mountain of decisions before the next note. The American avant-garde John Cage et al., was in the direction of freedom, and what I noticed right away was that the end result sounded pretty much the same.

I established this for myself when I was in the Air Force. I was a computer programmer, and we were allotted time on the machine to sharpen our programming skills. So I wrote a program to compose music. I was taking the readout from it in a very avant-garde European style. Then, as I was transcribing it, a light went on and I realized, “I don’t need all those computations.” It’s like when you walk, you don’t think about how to balance yourself, how much force is required or where to place your landing foot. When you’re riding a bicycle, you don’t objectify it at all, you just do it.

Rock and jazz improvisation are already there. There is a massive number of templates to absorb—chords, scales, licks and any gradations in between those. But, one player after another—from Charlie Parker to John Coltrane—put that all aside so, when you’re playing, you just play.

When you were programming in the Air Force, were you using punch cards?

Yes, 80-column Hollerith code. I eventually got to where I’d be programming in machine language. We were trained on the UNIVAC, which is the second generation after ENIAC [the first programmable, electronic, general-purpose digital computer]. So that was really close to the beginning. Compared to these wizards with computers today, I feel like I’m a biplane pilot.

Stepping back a couple years to Berkeley in 1961, what are your memories of meeting Phil?

On a lark, I went to Morrison Hall, the music building at UC Berkeley, to take their placement exam for where they’d put you in the music department. Mind you, I was already taking courses in chemistry, physics and astronomy at the time. During a lunch break, we were out in the hall talking and we hit it off right away. [Editor’s Note: As Lesh describes it in his book, Searching for the Sound: “I was waiting to take an ear-training test, when I heard someone say in a clear, confident voice: ‘After all, music stopped in 1750 [the year of Bach’s death] and began again in 1950 [the emergence of the postwar serialists.]’ Aha! Someone who knows about the avant-garde!”]

The two of you shared a memorable moment while working on the performance of a John Cage piece. How did that come about?

I was rooming with Phil at the time in an apartment about a block away from the university. We found out that Luciano Berio, the avant-garde composer, was coming to give a course at Mills College, and we signed up as auditors. It wasn’t for credit—we weren’t students there—but we signed up and we attended his lectures.

This led to several avant-garde performances with Berio. In fact, one of them featured a piece of my own. There also was a performance of John Cage’s Winter Music, which is a bunch of pages that are shuffled and dealt to the various players. There were two pianos onstage for Luciano Berio and Robert Moran, then there were about 15 of us up in the practice rooms.

You would see this little squiggle on the page and interpret it a certain way, so you had a lot of leeway. I made this incredible Don Martin [Mad magazine artist] sort of sound—KLOON KA-BANG! It came out much more amazing, dare I say, than I thought it would. So I said, “I’ve got to check this out with Phil.” Then as I go out in the hall, what do I see? Phil coming down the hall toward me. It turns out, we thought of doing the same thing at the same time.

Did you have any interactions with John Cage around that time or subsequently?

I met him several times. I found him wonderfully gentle and personable. He knew about that performance and he was as amused as we were.

After your first year at Berkeley, you traveled to Europe for an extensive music tutelage. That was through Luciano Berio?

Yes, I showed Berio some of the music I’d composed, and he was sufficiently impressed to arrange for scholarships to study at Darmstadt, with him in Italy and also in England at the Dartington Festival, which was amazing. Luminaries were there, like Vlado Perlemuter, the pianist, who had studied the music of Ravel with Ravel. He had this sparkling sound.

It was an idyllic period of my life. I had very little money in my pocket, but there were student tickets and discounts. I went to La Scala at least a dozen times. In fact, they were doing a Berio opera there, and for a while, I was a backstage urchin there as well. It was a magical time.

Eventually you returned home and joined the Air Force in 1965. What prompted that decision?

Well, I was a dropout, like Lillas Pastia in the opera Carmen, who had his tavern set up outside of the city walls, like an outlaw. I flew outside the box and under the radar.

I’d also compare it to an Indiana Jones movie, where he said, “Don’t ask me; I’m making it up as I go along.” [Laughs.] There was this military operation going on in Southeast Asia and I had received a draft notice. Now, nominally, the Air Force is all volunteer, so technically I volunteered, but that’s because it was a legitimate excuse to avoid getting sucked into the army, which I figured would be a worse deal. It probably would’ve involved a trip across the ocean, which I really wasn’t into.

Also at the time, there were some people in the Merry Prankster circuit, and other people I knew in California, who were furnishing me with samples of the then still-legal LSD, which I was importing to Las Vegas. In fact, there was a friend of a friend who came back with a truckload of peyote from Texas—also purchased legally at the time—and we would bargain back and forth. It was a rather psychedelic era and I had a cozy situation going on. I didn’t want to break it up.

During that era, while psychedelics were still legal yet underground, did it feel like a sweeping cultural change had been set in motion?

The fascination with it and the novelty of it were altogether stunning. We didn’t associate it with public events, like concerts of any genre of music. It was like Eastern mysticism or religious texts. Dr. Leary did the psychedelic version of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, for example.

When the Merry Pranksters appeared at Millbrook, they were shunned by Leary and his associates for taking a more recreational approach to psychedelics. It seems like the Acid Tests, the Grateful Dead and other like-minded music groups helped to alter that mindset. How do you remember it?

What happened was the psychedelic experience in the late ‘60s in San Francisco broke the surface tension between the various individual scenes. What you would find there in ‘64-‘65 was a group of friends, and it was a very small unit. Then in the later ‘60s, they saw that there were other such groups around town, and that broke the surface tension between them. So instead of a bunch of small groups, you had beginnings of a community.

You remained in touch with Phil over the years and eventually recorded on Anthem while you were serving in the Air Force. How were you able to work out those logistics?

I had leave time. I made Squadron Airman of the Month twice, and I made Airman of the Month for the base once. The base commander even put me up for Airman of the Year. Each one of those awards came with a three-day pass. So I had three-day passes up the elbow. I would cash one in and I would drive down to Los Angeles from Las Vegas for the recording sessions.

On Anthem, you used a prepared-piano technique that I associate with John Cage. Can you describe it?

One of the reasons they brought me in was because of my avant-garde attitude, leanings and experiences. That was the idea from the beginning, and I had several preparations installed, which I had learned from the likes of John Cage, Terry Riley and Dennis Johnson. You would put coins, screws or other things inside the piano strings so that they would sound different.

There was a transition at the end of “The Other One” into “New Potato Caboose,” where I picked up the sound and the momentum of it, threw it up in the air like a pizza chef and exploded it. Then out of the rubble came the next piece. I was using Hawaiian guitar steels on the bass strings to get a glissando sound. I also took a kids’ toy, a gyroscope, pulled the string, gave it a good yank and put it up against the sound board of the piano. It sounded much like a chainsaw. The producer, Dave Hassinger, could not see me because the sightlines were not good and Bob Weir said he cleared his seat by two feet.

You also played a harpsichord. Had that been brought in for your benefit?

No, it just happened to be there. It was just another toy in the studio. We were kids in the candy store. For instance, the 16 tracks available to us for Aoxomoxoa, we somehow managed to use all of them on every cut. It was like, “Hey, we have an open track here.” I think that’s when Mickey came in with a cowbell.

We actually had a couple of harpsichords. There was a newly made Baldwin electric amplifiable harpsichord. Then there was the one that we wound up using on “Mountains of the Moon,” a really classy Neupert harpsichord, except it wouldn’t tune up to a concert pitch. It didn’t have a cast iron harp like a piano, so it couldn’t take the string tension. So they tuned it a whole tone lower, and in effect, I played the piece in a different key.

You left the Air Force in November of ‘68, and immediately began touring with the Grateful Dead. You’ve said that Jerry Garcia had previously remarked, “I think we can use you.” How did you initially meet him and did you perform together at that time?

Shortly after I moved in with Phil, he said, “There’s a friend of mine down the peninsula I’d like to introduce you to.” We hit it off rather famously and Jerry came up to visit us in Berkeley a couple of times. We had what Jerry referred to as a “musical mutual admiration society.” At that time, he was playing Appalachian folk and Carter Family material.

But no, we didn’t play together until much later with the Grateful Dead. As you mention, less than 48 hours after being an Air Force sergeant, I was onstage with them in Ohio [at Ohio University’s Memorial Auditorium on 11/23/68].

You’ve said that when you were on top of your game with the Dead, you were channeling Lennie Tristano. Can you share something about him for people who might be unfamiliar?

I abjectly admired his playing. He was one of the best known bebop piano players, along with Teddy Wilson and Bud Powell. He was the piano equivalent of Charlie Parker. There are several others, though. Chick Corea is way up there, but Lennie Tristano was the one I imprinted on.

Given your classical background, you were drawing on a lot of seemingly disparate elements during those live shows.

There’s nature and nurture, but over 90% of it is the experiences you’ve had. Language is another example. As a teenager, I went to Germany, Italy and Belgium, and that necessitated becoming at least adept in those languages. I was predisposed to that because at the age of five, I learned my first second language. My mother and grandparents with whom I lived, spoke Norwegian. Then I went to the dreaded kindergarten and I had to learn another language—I had no choice. Crossing language barriers, crossing musical genre barriers, I don’t even think about it anymore.

Back to jazz musicians, can you recall someone from that world sitting in with the Grateful Dead or the Dead family of artists during that era?

Vince Guaraldi once sat in with us at the Avalon. I can’t tell you the date, but I remember it was at the Avalon. It must have been earlier on because the stage was in the corner. They hadn’t moved it across to the south side, next to the door to the dressing room, yet.

Is there another notable guest who comes to mind, not necessarily from the jazz realm?

I remember once at a festival in Louisiana, Jefferson Airplane joined us onstage. We also backed up Janis Joplin once at the Fillmore East.

You mentioned psychedelics earlier, and as it turns out, your time with Grateful Dead coincided with a period when you were abstaining.

Yes, I had been sucked into Scientology when I was in the Air Force. I wouldn’t even take an over-the-counter headache pill. They were very much anti any drug.

I remember the William Seward Burroughs quote to try and make it without any chemical corn. [In Nova Express, he writes: “They are poisoning and monopolizing the hallucinogen drugs— learn to make it without any chemical corn.”] Of course, he was into the white powder stuff, so I can understand it even better in that context.

But I was making a go for it; that’s all there was to that. It lasted a couple of years. Mind you, in some respects, it was an egregious example of horrible timing on my part. But there it jolly well was.

I imagine that didn’t altogether endear you to Owsley. You’ve said you were “chronically underamplified” onstage, which became frustrating and ultimately hastened your departure. You found other creative outlets almost immediately, though, including the play Tarot.

Tarot was a lot of fun. We came close to bringing in enough box office to keep the show going, but we fell short by a tooth width. The characters were all from the Tarot cards, and I did motivic character music to underline them because it was all in whiteface mime. There were no words. It was all gestures. Joe McCord [whose stage name was Rubber Duck] had studied mime with Étienne Decroux in France. It was a magical show.

Over the years, I’ve heard conflicting reports about Jerry Garcia’s involvement in Tarot. Did he have any role?

He showed up at several of the rehearsals in California before the show moved to New York. So yes, he was involved at the very beginning, before the show hit the boards. Richard Greene and Peter Rowan were involved as well. In fact, Peter Rowan contributed a song which wound up not making the trip to New York because he wasn’t there to sing it.

Back to psychedelics, in thinking about your collaboration with Bob Bralove as Dose Hermanos, my understanding is that the two of you indulged prior to all of your performances for many years. Is that a fair characterization?

Well, there was so much area to explore, and we needed to be motorized.

Was Henry Kaiser the person who introduced the two of you?

Yes, backstage at a Grateful Dead show in the ‘80s. There were times when I missed the entire show because I was backstage catching up with old friends. There was one night I did 250 years of catching up.

You’ve played many memorable “Dark Star”s over the years but there’s one on Henry Kaiser’s Heart’s Desire album that continues to stick with me. Do you have a particular recollection of that performance?

That was from a two-night run we had in Davis, California. It was a magical weekend.

I would also recommend any “Dark Star” that I participated in at the Fillmore East. Those are all magical and there are so many.

Once for a radio show, David Gans and I did a three-minute thrash version. It’s so adaptable.

How important do you think it is to have some amount of musical structure, which then gives you the ability to depart from it?

Well, even Stravinsky needed a concept, a trellis for his mind to strangle like a python. Jazz players have chord charts. There’s that necessity for the point of departure. Classical musicians are lost without the music in front of them. It’s the reverse of how to get a guitar player to turn down. [Laughs.]

Bob and I have definitely transcended all that, although we can do it as well. We don’t want to close doors anywhere. If you’re gonna go in the jungle with us, you better pack a pith helmet because we really go out there.