The Original Rebel Rouser: Duane Eddy

One afternoon in the early ‘90s, while sitting around a conference table in one of the major record labels’ offices, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s nominating committee was discussing who was eligible for induction that year. Label executives, music journalists and other august industry hoi polloi were tossing around names when the door opened and an uninvited guest walked in. John Fogerty had made the trip to New York for one reason only: to do his best to convince this board of tastemakers that they were overlooking someone important. Fogerty’s unexpected but impassioned speech worked and they inducted Duane Eddy in 1994.

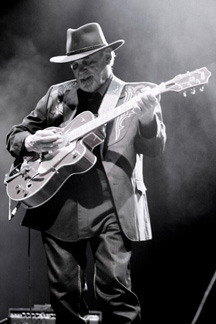

“Duane Eddy was the front guy, the first rock and roll guitar god,” Fogerty later said, and he wasn’t the only A-list rocker who felt that way. From The Beatles to Bruce Springsteen, Duane Eddy’s trademark “twang” guitar sound made a massive impression on future pickers. Between 1958 and 1964 he landed more than two dozen singles in the Billboard Top 100, and three of them – “Rebel Rouser,” “Forty Miles of Bad Road” and “Because They’re Young” – climbed to the top 10.

Without ever singing a note, Duane Eddy remains one of the most successful and influential instrumental artists in rock history.

Eddy never stopped performing, but like many of his early-rock peers he did slow down. His last brush with success came in 1986, when he collaborated with British synth-poppers Art of Noise on a remake of Eddy’s 1960 movie theme hit “Peter Gunn.” A subsequent album featured guests such as Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Fogerty, Steve Cropper, Ry Cooder and others. Then…nothing. “Nobody was interested,” Eddy says.

But now, someone is. Richard Hawley, a guitarist and producer best known as a member of the Britpop band Pulp, connected with Eddy and let the now 73 year old know that he was a fan. Before long, Hawley and bassist Colin Elliot found themselves ensconced with the twang-meister in a studio in Sheffield, England, producing Road Trip, Eddy’s first album of new material in a quarter-century.

“His dad had played him some of my things back in the day and told him, ‘When you can play this good you can call yourself a guitar player,’” Eddy says about Hawley. “He took it to heart and here we are.”

Road Trip avoids the retro trap but sounds just like, well, a Duane Eddy record – Eddy still plays the instantly identifiable twang on the low-note strings of a Gretsch guitar, with echo and vibrato front and center. “The twang developed because I got tired of hearing rock and roll licks on the high strings,” says Eddy. “It was always the same thing. I wanted to do something different. I thought, ‘Try playing down low.’ I knew that the low strings recorded stronger and more powerfully than the high strings.”

Born in Upstate New York, Eddy moved to Arizona during his youth; he says that the bigness and openness of his guitar tone owes much the vastness of the desert. While attending high school in the city of Coolidge, he met a young, ambitious disc jockey and aspiring producer/songwriter named Lee Hazlewood. Sensing a talent in Eddy that was worth nurturing, Hazlewood – whose own career would later take off in a big way – became the teenage guitarist’s manager and producer, took him to Phoenix, and before long, the hits arrived at a rapid pace.

Eddy became a sensation, touring the United States and abroad on package shows with other rock pioneers, appearing on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand and other popular TV programs, and maintaining a dizzying pace of recording three albums per year. Then, in 1964, rock and roll started to change. “When The Beatles came along, I thought, ‘Gosh, what a good little garage band,’” Eddy says. “I had no idea they were going to be as huge as they turned out to be. Nobody did. I was still having chart records but it was starting to wane at that point anyway.”

Today, Eddy is content. He still has a devoted fan base and his place in rock history is secure. “I came along with something different and I can still work,” he says. “I got more out of this than I ever expected.”