The Future in Sam Cohen’s Ears

The missing link between Danger Mouse and Kevin Morby strikes out on his own once again with a new, adventurous solo album.

The Future’s Still Ringing in My Ears came as something of a surprise to Sam Cohen, or as much of a surprise as a new album can be for a musician nearly two decades into his career. Sure, he had plenty going on—professionally, creatively and personally—but if you’d asked him if he was primed for such an undertaking, he’d probably say “no.”

As a part of Apollo Sunshine, Cohen had dispensed overloaded art-rock for much of the early ‘00s, living as a “rock-and-roll monk,” in his phrasing, but was finally settling down. When that band dissolved, he made a few gently psychedelic and self-produced pop albums with his band Yellowbirds, then shifted to projects under his own name. He started a family. And, around the time of 2015’s Cool It, his new job sort of took over.

Not that his new job isn’t conducive to music. Quite the opposite. Every day, Cohen commutes to work at the Saltmines. A labyrinthine basement in Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood, the complex serves a large slice of New York’s professional musical class, working in adjacent studios and hoping the pipes don’t burst.

“The biggest thing the first Yellowbirds record did for me was start a new career,” remarks Cohen. “It was just friends at first, being like, ‘Hey, you should produce my thing,’ and I’d be like, ‘Oh, funny, I’m not a producer.’” But yet, no one else had made a record sound like that, so Cohen took the credit. After recording basic tracks in a studio, “the rest [was done] at home with an Mbox and a Shure SM57, and I just sort of willed it to be cool.”

That will toward coolness, an extension of Apollo Sunshine’s resourceful anarchy, became a space of its own, and Cohen found himself as an in-demand producer around his Brooklyn musical universe. Cool It had (to quote Spinal Tap manager Ian Faith) a selective audience. “I wouldn’t say nobody gave a shit because I got really heartwarming, amazing feedback from a range of people, but it certainly wasn’t a breakthrough,” says Cohen.

But among that selective audience was Brian Burton, the producer professionally known as Danger Mouse, who found himself “blown away” by the song “Pretty Lights.” The album grabbed him, especially “the sounds, [and] the sudden changes in the middle of songs. I immediately tried to find where this music came from.”

“He reached out and was like, ‘I feel like we could co-produce some stuff,’” Cohen recalls. “It blew my mind. When Brian showed up in my life, it gave me a bunch of encouragement. I think it’s very safe to say that the sense of urgency was not there. It was great, like, ‘I have someone who believes in me. Maybe there’s a reason to get going.’”

Not only did Burton give Cohen encouragement, he also almost immediately pulled him into his circle of collaborators. When a session scheduled for another artist was canceled, Burton suggested that they play around with one of Cohen’s newer songs. Except, for perhaps the first time since he was a teenager, Cohen didn’t have any. What they did have was the cool-sounding noise a synth was making.

“You just need a place to start,” Cohen says. “Brian talks about this all the time. We know how to make cool-sounding music. We just need to pick a direction and go until a song exists. That’s really it. You’ve gotta show up to work on time and do your job all day for the stuff to materialize. There’s no substitute for that.”

As a musician, the high-speed pursuit of the muse into the bowels of the modern-day recording studio is something of a new skill set for Cohen. Growing up in Houston, he was “playing out in bars all through high school and singing my songs. I was into studying guitar because I had an amazing teacher, Clayton Dyess—a monstrous jazz guitarist who’d done many tours with Dizzy Gillespie. He got me really into jazz guitar, which was linked to rockabilly and Western swing, which was the stuff I was into then.”

Cohen’s skill set expanded considerably when he enrolled at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, where he quickly learned that he didn’t necessarily like taking guitar lessons; he just liked taking them from Clayton Dyess. “The idea of learning jazz guitar in Boston ceased to be a cool thing to me, and I had a real reaction to virtuosity.”

Three albums with Apollo Sunshine followed, and Cohen picked up other talents. He played pedal steel and autoharp. Inevitably, as anybody in a band does, he tried his hand at his bandmates’ instruments, and realized he had an aptitude for the drums, too. Settling in New York during Apollo Sunshine’s final days, Cohen also picked up gigs as a regular ol’ guitarist, often jamming in the circle of musicians around The National, as well as sharing a studio space with pal Joe Russo.

And from Burton, Cohen learned a new method of songwriting. During the Los Angeles session that became “I Can’t Lose,” now the first track on The Future’s Still Ringing in My Ears, Fabrizio Moretti of The Strokes “came in and played that bass hook and added layers of harpsichord and acoustic guitar.”

From there, Cohen brought the noise and new layers back to Brooklyn, and “worked and worked and worked on it. I’d send it over to Brian. We were grabbing bars and pasting bars and rewriting it. Everything got a little herky jerky, and I was editing sloppily and lost the plot—things were getting out of time. I rerecorded everything in the middle after we came up with the structure. It’s a very Brian way to work. He’s got such a great aesthetic. He and I see really eye-to-eye in our influences, in the texture of the music—like, tape-y and tube-y and a little dusted sounding, but the process couldn’t be any more modern.”

“I saw from working with him that he was only concerned with the music and it taking whatever shape it needed to,” says Burton. “He’s been my biggest collaborator over the past few years, and it’s clearly helped the music I’ve been involved with.”

The Los Angeles session was a quiet milestone in Cohen’s still-developing career, yielding the seeds for “I Can’t Lose” as well as “Lose Your Illusion,” which became one of the first songs released from the debut album on 30th Century Records, Burton’s new label. With Burton, Cohen played on sessions for artists including Karen O, where he also earned some co-writing credits.

But despite moving in some high-profile circles, Cohen’s keeping a veteran indie musician’s eye on the proceedings and his place in the pop machinery. “I’m there if [the song] needs it,” he says of his contributions as a session musician. “I don’t love the whole co-write culture. When it’s organic and there’s some trust there—and there’s a reason—it can be cool, but it can be strange at times. If I knew how to make music for money, I guess I probably would, but I can only really function if I’m really feeling the music.”

Cohen mentions a few of the organic collaborations he’s been a part of in recent years, including songs he co-wrote on Sharon Van Etten’s acclaimed Remind Me Tomorrow, as part of a project that didn’t fully pan out. He also stepped into a natural partnership with Kevin Morby, producing him in the studio and even joining him on the road.

“I’m extremely proud of the Kevin Morby record [Oh My God],” says Cohen. “He and I worked well together. There was discovery. We found a new way to present his songs that he was so game to explore. It’s so rewarding when what I envision for the artist lines up with what they want to do. Sometimes there’s a compromise but, with that one, it felt like all our energy was pushing forward.”

Cohen blocked out weeks of solo time between his production jobs to work on his own music, picking up and putting down songs as needed. “It’s very similar to having a room full of easels and going from painting to painting and being like, ‘You know, a little yellow across the board. I’m just gonna do some highlights here and here…’”

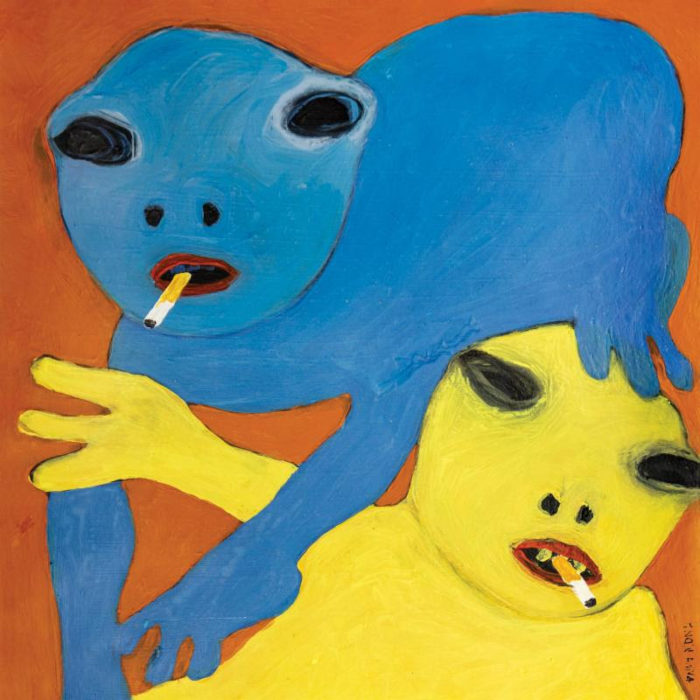

The resultant album, with Danger Mouse as a co-producer, is another new step for Cohen, an overblown psych-pop confection of fuzzed sounds, playful scene changes and Cohen’s affable voice. On the spectrum of modern production, some of it veers toward the overblown territory of The Flaming Lips’ sonic mastermind Dave Fridmann, but mostly it showcases Cohen’s emerging fingerprint as a studio creator. Some of Apollo Sunshine’s anarchic spirit is there, but so is the more refined skill set he’s acquired since then.

Cohen’s two-rooms-and-a-hall corner of the Saltmines is called Jupiter Recordings, named for one of his daughters. A pedal steel is parked in the hall and paintings by the New York artist Steve Keene, known for the cover of Pavement’s Wowee Zowee, hang on the wall in the live room. The Keenes in Cohen’s collection include The Smiths, The Clash, and (most amusingly) the Pavement reunion. The space is somewhere between DIY and a professional, traditional recording studio—perhaps a microcosm of the modern music industry at large.

There isn’t a shared water cooler in the Saltmines, but the musicians collide frequently. “You see people out in the hall going to the bathroom, or just visiting, checking in with someone and saying, ‘I’m going to lunch right now’ or ‘What are you working on?’ My friend Steve Schiltz is down the hall. He’s got the band Longwave and does music for ads all day in there. He’s got this crazy collection of guitars,” says Cohen.

“A lot of the people I’ve worked with are in this building. Joel Morowitz, who co-owned [Apollo Sunshine’s former label] SpinART, is upstairs. Now he has this microphone company and sells vintage mics, so I rent stuff from him all the time. My best friend Josh Kaufman is upstairs on the fourth floor and we work together all the time. I’ve had all these people here who’ve been very helpful in guiding my learning.”

Apollo Sunshine didn’t quite work out as planned for Cohen. Nor, for that matter, did attending Berklee, or even releasing his last solo album. And yet, each produced unexpected plot twists that resulted in compelling music, links in the still-developing path of Cohen’s career.

“The future’s been a terrific disappointment” is the first line of “Something’s Got a Hold on Me,” the record’s first single, and a darkness runs through the lyrics, but it hardly qualifies as a bummer of an album. The Future’s Still Ringing in My Ears splits the difference—a thoroughly modern comedown, but just as much a kaleidoscopic, pleasure-making soundscape of vintage swirls, fat bass and playful harmonies.

In other ways, it’s not that different from everything that Sam Cohen’s done before. “I’m not like Madonna or David Bowie,” he says. “I don’t have a new outfit for this cycle.” But the Sam Cohen costume he’s wearing remains pretty convincing, and even capable of new tricks this deep into his discography.

It’s impossible to know what The Future’s Still Ringing in My Ears will yield, except perhaps a few earworms for listeners, and—inevitably—more music from Cohen. He’s moved on to what’s next, working (and sharing much of a band) with Kevin Morby, playing in various live configurations around New York and reporting to work in the Saltmines, where more weird noises await.

This article originally appears in the September 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe below.