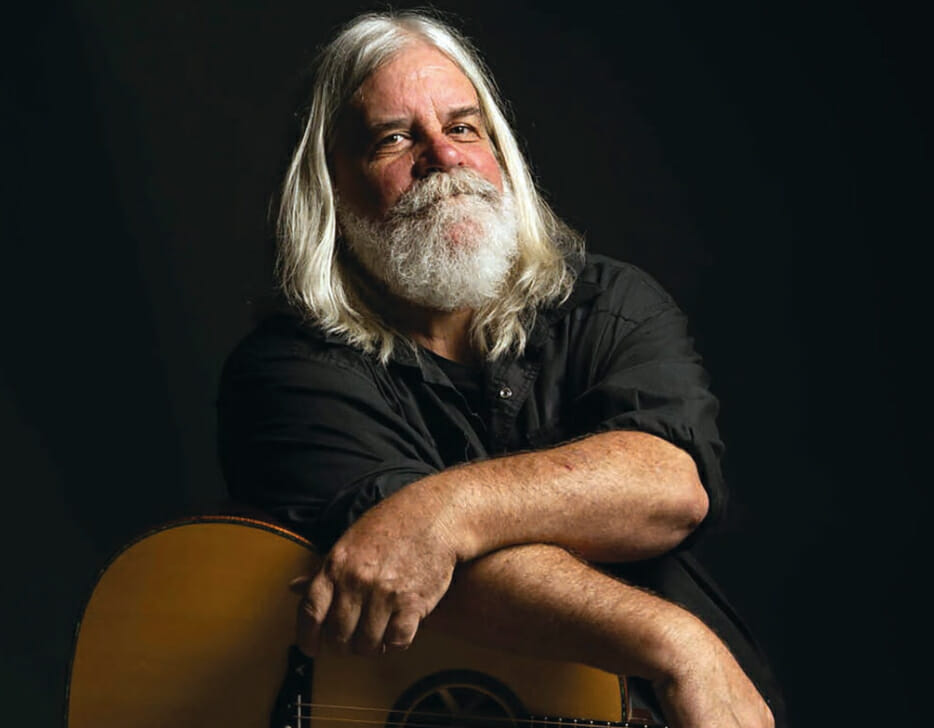

The Core: Vince Herman

photo: Michael Weintrob

***

The Leftover Salmon frontman embraces a new Nashville frontier on his long-awaited solo debut, Enjoy the Ride.

The Bus Stops Here

My way to get out there while still being safe during the pandemic was to buy an RV, which I saw as my own little bubble. Just as the pandemic started—when all the lockdowns happened— I moved into a place by myself for the first time since I was in college probably, and I sat there in Colorado for four months totally alone. My kids were afraid to come over and, after being a road dog for over 30 years, sitting in one place felt like being stuck at a hotel waiting for a bus that never arrives.

So I thought, “I better buy my own bus.” [Laughs.] I got an RV and cruised across the country for a while. I went up to the Pacific Northwest first— I had some things to clean up in Oregon after successfully completing my third marriage. [Laughs.] So I grabbed some stuff from there, went to see some friends and came back down to Colorado for a bit. And then I started heading east and up through Wisconsin. I saw a bunch of friends in Illinois, Kentucky, West Virginia and Pennsylvania. And then I ended up in Nashville and that’s where the bus stopped.

I ended up spending a month in Nashville and hooked up with this writers’ community. I did a bunch of co-writes and saw the writing on the wall that this was something that I needed to be involved in. So I went back to Colorado, got my stuff together and moved it all out here to Nashville. I found a house in Madison, Tenn., and I’ve been loving it ever since. Enjoy the Ride is the result of that move and all the folks I’ve been lucky enough to write with here.

The Nashville Way

A couple of songs off Enjoy the Ride came from my first venture out here to Nashville. But, the writing started more in depth on my return to town. I’ve writ[1]ten more songs in the last few years than I have at any point during the rest of my life. It’s just night and day, this whole thing. I’d never done a co-write before coming out here, and that just changed everything for me

I ran into my buddies Chris and Donnie Davisson—my old West Virginia friends who have a great group, the Davisson Brothers Band—and they set me up with this writing community they’d been working with. I got a publishing deal through their manager Erv Woolsey, who also manages George Strait, and we developed a great friendship. We have a common appreciation for Texas swing music and he helped set up a bunch of writing sessions. We had a big one for our buddy Andy Frasco, when he came into town, that a bunch of the writers got together on, and we just continued setting up these writing parties. I’d never done anything like that before.

Generally speaking with these writing sessions, you get together with one or two other people, you sit together for about four hours and you leave with a song—sometimes two songs. That’s the Nashville way.

You sit around, you talk for a while about what’s been going on in your life or current events and you tell some stories. Sometimes a phrase might catch someone’s ear or a topic might come up that everyone wants to write about. Oftentimes, these guys will come in with a book of titles and you’ll write toward this or that title. But, generally, you don’t come in with a song three quarters of the way written because you wanna harvest the creativity of the pot of writers you are working with. You wanna utilize everyone’s ideas and start with a blank slate.

A Real Education

Now that I have a publishing deal, after I write a song, I’ll send it to my publisher, who then does all the copyright stuff and begins to pitch the song to other performers who are looking for music. And after a year or so, I ended up with this big batch of songs that no one was biting on. So I was like, “Well, they’re really good songs, and I wanna get ‘em out.” And that’s when I met my producer Dave Ferguson. Ferg was working on the Davisson Brothers Band’s record when we met, and I asked him if he’d be willing to do one with me. And that process was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced before when making a record. Usually, you take the songs out on the road and you work them out. So when the band goes into the studio, everybody knows the songs. This process was totally different. I’d send a recording of a rough arrangement of a song to the bass player on the session, Dave Roe, who was Johnny Cash’s bass player for a long time. He’s just a real old-school Nashville dude. He would write up the charts and, the next day, we would already be in the studio recording these tunes with some folks that I had never met before.

I was panicking—absolutely panicking. I’d paid for this album myself for the first time ever so that was a bit of a burden, and I didn’t even know these guys. But, by the end of the first day of recording, I was just living in a new world. These players are so good—and so creative—and they meshed their parts together so beautifully. It’s been a real education for me.

I had some old friends in the studio, too. Jason Carter from Del McCoury Band did some duel fiddle with Bronwyn Keith-Hynes, and Darrell Scott, who is one of my absolute favorites, is on there. Pat McLaughlin—who was John Prine’s guitarist for a bunch of years—and I wrote a couple of the songs on the record with Ferg, and Pat played on a lot of the stuff as well. He’s just an exemplary Nashville cat, man.

I also had Tim O’Brien do some vocal stuff. Tim is my role model in music—I moved from West Virginia to Colorado pretty much to check out the Hot Rize scene back in the ‘80s, so to have Tim on the record was a full-circle thing for me. And Ronnie Bowman, who I wrote a couple of the tunes on the record with, agreed to do some vocals on a tune.

I was also excited to have my son Silas on the record, and I’m excited that he is also heading out on the road with us. He’s a phenomenal player, who’s been doing a lot more engineering and production work lately, so I’m really glad to get him back into playing more. I just get such joy out of playing music with him and he’s so freaking good. We played a whole lot when I lived in Colorado—we were playing all the time in the house, which had a full-band setup in the basement. I’d play with Silas and a bunch of his high school buds growing up, as well as my son Colin. We would always have a blast.

Can We Talk?

I’m gonna try to keep my solo repertoire separate from Leftover Salmon so people can expect something different than they would see at a Salmon show. I want them to live in different worlds, but one of the reasons I made this record is that I’m a fan of country music. And I’ve always thought of Salmon as a country band. You can look at the Grateful Dead as a country band—to me, bluegrass, cajun music, ballads and all that stuff is what makes up country music. Hank Williams, when he debuted on the Opry, was playing Cajun music, and Bill Monroe had an accordion in his first band. So when all of that goes through the filter of my mind, it all comes out as country music, and this record is an attempt to make a statement about what country music is to me. The Dead and The New Riders of the Purple Sage were my window into country music, just as the Dead were a window into bluegrass music for so many people.

But, though I’ve always seen Salmon as somewhat of a country band, the country and jamband worlds are absolutely miles apart—not so much musically, but culturally. And at this point, so much of this country needs to come together, with all the walls between the different sides and all the perceived little niches that we’re supposed to stay in, man. We need to come together as a country. And music can play a big role in that. So I guess you can say that I want to bring the hippies to country. I want to say, “We’re kind of doing the same thing here, folks. Can we talk?”

The two communities don’t have to be so far apart. Coming to Nashville as a jamband guy I thought, “Man, these writers in town will probably have no knowledge of what I’ve been doing for 30 years.” And I found it to be quite the opposite. A lot of the folks I wrote with on this record said, “I’ve been seeing you for years, man.” My buddy Aaron Raitiere, who is one of my favorite writers here, said to me: “I was 15 years old when I went to see you for the first time. You were up there yelling about corn and throwing it at the audience for like 10 minutes. I had no idea that you could do that in music.”

Going Solo at 60

It seems kind of absurd at the age of 60 to be starting a solo band and to have a new career, but I’m hoping we can get folks out and that I don’t have to sell my house or anything while I try to do this. [Laughs.] Salmon is also getting out there. We’ve got a new record getting mixed and readied now—we recorded it a couple of weeks back. It’s our bluegrass roots record; it’s a lot of the tunes that influenced some of our big influences, as well as some other slightly out of the bluegrass catalog music. On the touring front, it also looks like we might also get our first trip to Europe on the books for sometime in the next year. So we’ve got some good things in the works—playing some good festivals and keeping the train rolling in the Salmon world.

I’m also involved in a Jerry Garcia exhibit at the bluegrass museum in Owensboro, Ky. I’ve had a little bit of a hand in helping that come to fruition; I have some interviews with David Nelson, Eric Thompson and Sandy Rothman coming up where we are gonna talk about Jerry’s bluegrass music, how they first got exposed to bluegrass and the trips that they all took to see some bluegrass at those festivals early on. Garcia brought so many people to bluegrass, but the bluegrass community has yet to really embrace that.