The Core: Bob Weir & Don Was on Wolf Bros

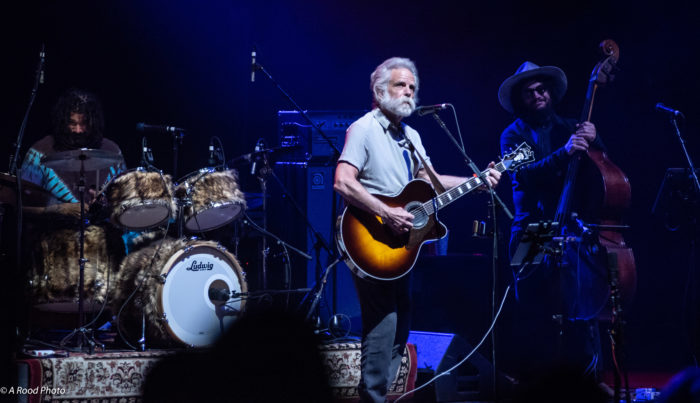

photo by Steven Rood

THREE AMIGOS

BOB WEIR: The notion for this trio [Wolf Bros] came to me out of a dream I had about playing with Don not long ago. So we tried playing together with Jay Lane and it worked well. Don and I have known each other for a while and had played together a few times recently. We were introduced by Rob Wasserman 20-something years ago—we were gonna do a project back then with Rob while he was working on his Trios record, but we ascertained it looked like too much fun and decided to try it out another time. I had already done one of those trios with Rob and Neil Young.

DON WAS: And I also worked on Trios with Brian and Carnie Wilson. There was gonna be another record, but he just never got around to it. Bob and I did get together in Pasadena back then to have breakfast. We definitely have chemistry. There was a moment when we did Warren [Haynes’] Christmas Jam together in 2016; we were supposed to switch to electric bass and electric guitar, and Bob just stayed on acoustic. We were doing some Blue Mountain songs, and then we went into “Eyes of the World” and I stayed on the string bass and Branford [Marsalis] came out. He was sharing a microphone with me—and that’s when I realized that, in the Grateful Dead world, there is a point when this wave comes in. It’s like surfing a wave that’s a little too big and you are trying to stay onboard. [Laughter.]

My fingers were moving in a way that was disconnected from my brain, and I just got swept away in it. It was a transcendental experience. Of course, your brain starts making every neurotransmitter associated with pleasure—fire, adrenaline. Between the combination of what was happening onstage with that band, and the audience’s response, I just wanted more of it. And I understood that’s what goes on in the great moments of Bob’s bands. At the same time, I’m still running a record company [Blue Note]. I’m not denigrating lawyers or accountants—they’re essential and they’re nice people—but if you go into an office every day, you can forget that it’s that wave and that exhilaration and that ecstasy that makes music and the music business work. It just seemed like something that was essential to being alive.

REALMS OF POSSIBILITY

WEIR: Part of that experience [of having a small combo] is that, when you get there, time goes away and, to a greater extent, the physical world also goes away. It’s like being in the dream world. Stuff that would be impossible in the physical world—like levitation—seems totally doable. You’re doing things with your hands that you haven’t rehearsed but, in the dream, your hands can do this and they can do that.

It is the same with singing—you are going for notes that may or may not be there and which definitely wouldn’t be there if you weren’t electrified. The realm of the possible becomes much larger and all sorts of new things occur to you. If you’re playing or singing a song, the character in the story will often show you a whole new side of his or herself. With that comes notes, phrases and all these colors. The inflections are part of that character’s personality—the character’s flesh and bones. Sometimes they just step out, time stands still, all the colors are there at once and it’s just a magical moment.

WAS: That’s so wild, Bobby. Not being a singer, I’ve never thought about these characters slowly being revealed. I only think of it in terms of notes, but that’s incredible. When we first met up with Jay, Bob suggested six songs to focus on, and then when we got to the place and played, he called out “Even So,” which wasn’t one of the six. He just started playing it. We instantly fell into a deep, funky groove that was just effortless. You could tell in the first minute and a half that this was definitely going to work. We feel the beat in the same place. And I love Jay’s pocket, man. It was real easy to lay notes down and get right to the bottom of it. He’s just got a great feel.

To me, Phil Lesh is a total virtuosic genius. So the challenge is: How do you approach these songs without thinking about what came before, and approach it from a beginner’s mind? To me, there is a common link and sensibility between all the Dead’s songs from every period in the way they move through the changes and the overall shapes of things. That’s why Bob can draw from all of his musical eras, in any of his configurations, and the show is still cohesive. It’s a three-way conversation, and we’ll see what we’ve got to talk about. [Laughter.]

BOUND TO COVER JUST A LITTLE MORE GROUND

WEIR: We’ve got a lot of ground to cover. We’ll do about half of the Blue Mountain songs but, really, what I’m gonna do is let Don and Jay pick the songs that we are going to do because these songs are like my kids, and I can’t choose between them. So I’ll let the cousins steer me toward what to do. [Laughter.]

These songs love to put on a whole new set of clothes—they love getting dressed up or dressed down. They just take such delight in it; you can feel the song come alive over this accoutrement or that. Jay’s really chameleonic. It can be a problem—sometimes, he gets tripped up. [Laughter.] For instance, I remember there was a period with RatDog where he was into all these New Orleans feels, and no matter what you were playing, whatever you set your watch by, he was gonna come up with some New Orleans rhythms. [Laughter.] Like it or not, you’re playing down on Bourbon Street. But, he’s gotten a little more judicious. [Laughter.]

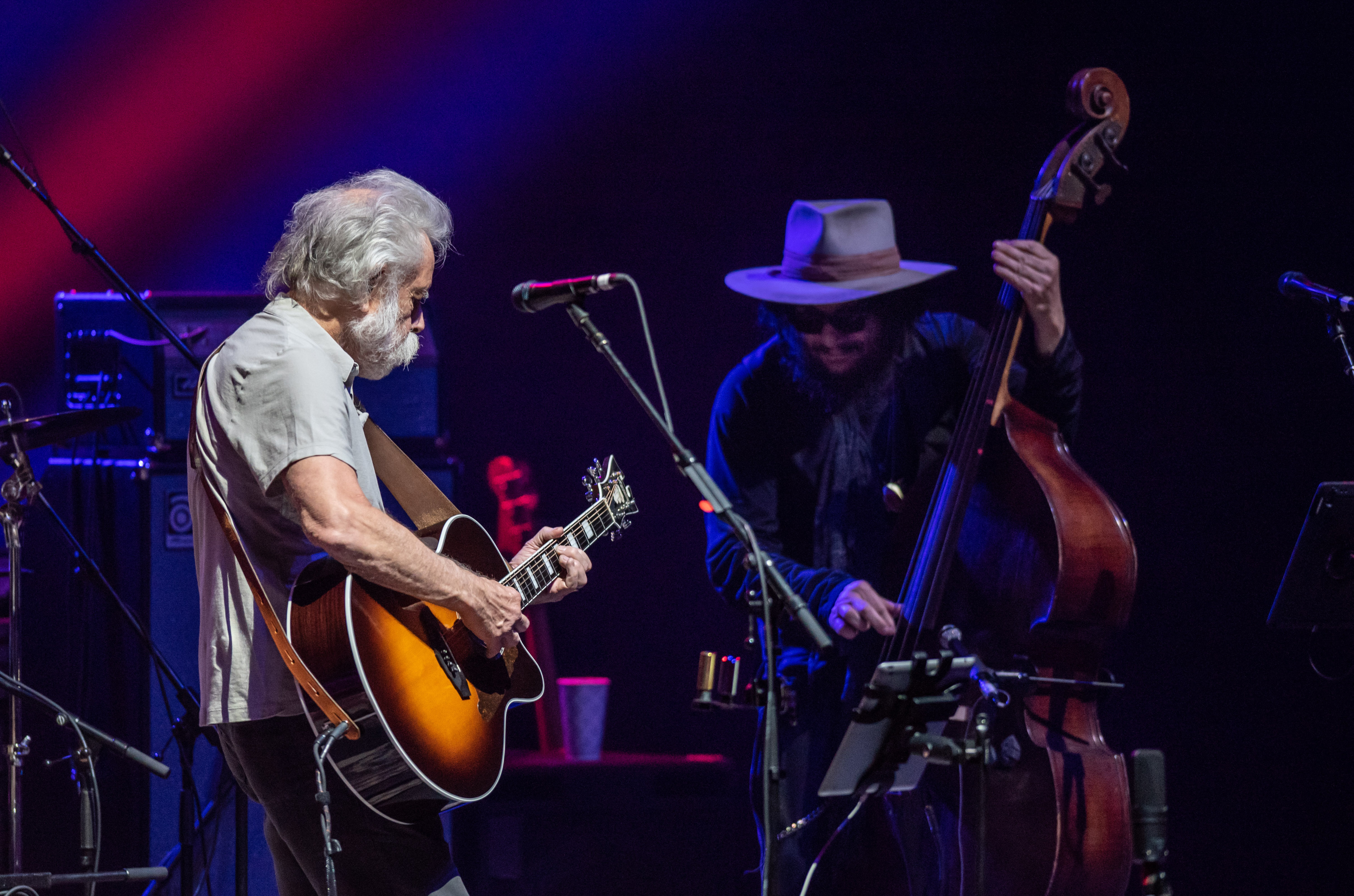

Wolf Bros: Jay Lane, Bob Weir, Don Was (l-r)

Wolf Bros: Jay Lane, Bob Weir, Don Was (l-r)

WAS: To be honest, Bob, I don’t see a huge disconnect between [the Blue Mountain material] and your other songs. One of the things I like about that record—and that’s influencing me going into the Wolf Bros adventure—is how great your vocals are on that album, man. A lot of that has to do with the fact that you’ve got the space to phrase, so you can breathe. It’s vocal-driven. I hope we can really maintain that with the Wolf Bros. It’s less about the number of notes and more about the shading, dynamics and space.

One time, I asked Ziggy Marley, “What the fuck? How did Family Man [Aston Barrett, bassist who played with The Wailers] come up with those bass lines?” [Laughter.] And he says, “It’s really simple. It’s a conversation between my dad and Family Man.” And listening to those records in that context makes everything he’s playing make total sense. So I’m excited about that prospect.

BORN-AGAIN DEADHEADS

WAS: I was in my prime teenage years when the Dead were just getting started. There’s not a huge age gap, but it’s enough. So I was a fan and have always been aware of them. But the thing that really reinvigorated my interest was when I started recording with [John] Mayer. We did Born and Raised about seven years ago. I was surprised to find out how huge a Dead fan Mayer was. That’s what he was listening to all the time, even when we were just driving around. He started pointing out nuances in their dynamics—the shape of what was happening— that I’d forgotten about and that I had never been aware of. Then, a few years later, Bob and Mickey [Hart] came over to my office to talk about a bunch of records they were thinking of making and releasing. John was recording a new album downstairs at Capitol Studios, so I said, “You better come up here.” [Laughter.] And the chemistry was pretty instant.

WEIR: With John, there were sparks immediately [which led to Dead & Company]. One of the things we are going to do with Wolf Bros is wade deep into all the different music we all dig. I can almost guarantee that what we’re doing at the beginning of the tour will be quite different than what we’ll be doing at the end of the tour. It’s not like we’ll go out there and have a repertoire we’ve worked up. We’re gonna be on a bus together and, after a show, you hop on the bus, head to the next city and you’ve got nothing to do but listen to music. So we’ll be playing each other our favorite records from this idiom and that idiom and see what plums we pull out of that pie.

GOLDEN CIRCLES

WAS: We got together long enough to know that we could get a groove going between the three of us, but the direction we take is yet to be determined. I’ve been listening to some interesting trios, particularly Ornette Coleman, because there’s something interesting about the way Bob picked up the electric guitar in the two days we played together. It was a single- note guitar, a single-note bass and drums. There’s all kinds of space.

There’s a Blue Note album called Ornette Coleman Trio: At the “Golden Circle” Stockholm— it’s two volumes, and the interplay there is quite interesting. I also enjoy the interplay that Ornette had earlier on in his career with his drummer Charlie Haden and his bass player Danny Thompson. Danny’s still around, still plays beautiful tones. It’s basically acoustic with drums.

WEIR: I fondly remember them. Jerry was a big fan. We went and saw them one time when they were playing in San Francisco. We had a great time with them. [Laughter.]

I’m loving the trio configuration because it’s not easy to achieve—with Ornette, it’s not just the note he’s playing, but the space around the note. It’s all part of that overall color. If you get a bunch more instruments involved that stay around the note, it disappears.

In a small ensemble, there’s a whole lot more room. The other thing about a small ensemble

is that the sound of the room you’re playing in also becomes a big part of the picture. And that’s wonderful fun. If the room has a certain sort of reverb or echo to it, then you play with that. It becomes part of your palette. If there’s a slap-back echo, then you’ve gotta find the rhythm and play in time with that, or the song’s gonna die. A lot of that stuff just can’t happen when you start adding a whole bunch of other instruments. That being said, over the course of the tour, we’re probably gonna plug in a few friends here or there as we come into a given town.

For instance, if we’re ever in the neighborhood with Branford, we’re gonna invite him down. [At LOCKN’], as ever, playing with Branford was sublime. He adds so much juice to the music. Whatever color you’re going for, he can help you really redefine that color. If you’re going for smoky blue, he can help you achieve a shade of smoky blue that is unique to that night and that song, and you’ll probably never hear that again. He’s magical.

This article originally appears in the October/November 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.