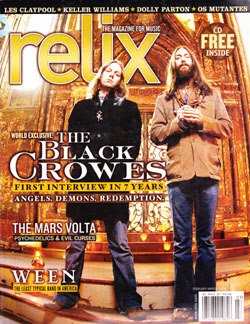

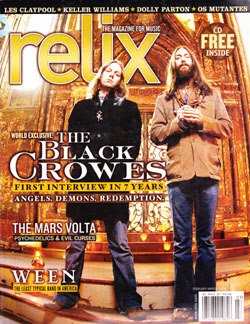

The Black Crowes: Redemption Songs (Relix Revisited)

With the Black Crowes back on the road once again, revisit this cover story from the February-March 2008 issues of the magazine.

The striking building that houses the Angel Orensanz Foundation for the Arts on the now ultra-fashionable Lower East Side of Manhattan was built more than 150 years ago. Now a performance and exhibition space, it is the city’s oldest surviving synagogue, and a rare architectural example of a Gothic synagogue, a kind of fusion of Jewish and Christian aesthetics. It had been abandoned and run down for decades, before being purchased in the mid-‘80s by Angel Orensanz, a Spanish-American sculptor. Now the neighborhood is on the upswing, and the gorgeous building itself stands as a dignified reminder of deep spiritual traditions and rich, dynamic communities that preceded the inexorable gentrification of Manhattan.

Angel Orensanz is a fitting setting, then, in which to meet with Chris and Rich Robinson of The Black Crowes, who, after all, wrote “She Talks to Angels.” The Crowes, too, are on the upswing. After splitting up acrimoniously in 2002, the band re-formed in 2005 and is now about to release Warpaint, the group’s most confident and instantly appealing album since the raw, raucous Shake Your Money Maker first brought the group national attention in 1990 – and sold more than five million copies to boot. In addition, the Crowes, too, see themselves as symbols of vanishing values. Sometimes disparaged, run aground for a stretch, newly energized, the brothers Robinson view themselves and their band as keepers of the rock and roll flame in an era in which slickness, irony, self-indulgence and soulless technology threaten to plunge the music world into darkness. Their new album is called Warpaint for a reason.

“It’s the perfect title for where we are,” Chris says. “There are clandestine messages in there for people who like rock music.”

“Chris came up with the title,” Rich explains. “It was a song he had written [that is not on the album], but that he felt would really suit the record. It’s an aggressive stance, but coming from an organic place – aggressive on a grassroots level. It’s sincere music. That is the war. Simply to make this record and put our sincere feelings on the table is a statement unto itself. We don’t write songs to try to be Justin Timberlake or any of those people. We just do what we do. Some people like it, a lot of people don’t – whatever. To have that focus in this world of distraction is like a silent protest. It’s like, ‘Hey, you don’t have to do all that bullshit. Sometimes you can find some sincerity in life.’”

“Everything is squeaky clean,” Chris later complains about the current music scene. “Even the punk-rock bands are clean. You’re not supposed to get your hair done that much, you know what I mean? You’re supposed to look like shit because you did it yourself and you never bathe. You can’t be punk rock if you buy all your shit at Fred Segal in Hollywood. That’s just a rule!”

He pauses and laughs. “I saw Black Flag in the ‘80s, all right? I know the rules, see? It doesn’t matter if I’m a head or not. I know the rules!”

Even on a bright winter afternoon, the main room of Angel Orensanz, with its dark wood floor, vaulted ceiling and stained-glass windows, is thick with shadows. Chris and Rich are about to have their photos taken, and they’re hanging around, casually chatting. An iPod plugged into speakers plays The Byrds’ “Eight Miles High,” a groundbreaking statement of psychedelic rock from more than forty years ago. As that song ends, Chris turns to his brother and, alluding to one of the few surviving record stores in Manhattan, says, “The next time you go by Other Music, you should check out this new album they have by Gene Clark,” one of the founding members of The Byrds who died in 1991. Rich listens and nods.

As they chat with the photographer and pose for their shots, the two seem cordial enough, though hardly close. They stand next to each other with a certain formality, and seem eager to be done. Still, none of the animosity that made the duo infamous in ‘90s as battling brothers along the lines of Phil and Don Everly, Ray and Dave Davies of The Kinks, and Noel and Liam Gallagher of Oasis (with whom The Black Crowes wittily hit the road for a “Brotherly Love” tour in 2001) flamed up at all. Perhaps after reassembling The Black Crowes in 2005, touring again, doing some live dates as a duo, and completing their first album of new Crowes material since Lions in 2001, the Robinsons have matured. Chris is 41; Rich is 39. Past a certain point, that “battling brothers” thing just isn’t cute any more.

Like so many fractious musical partners before them – the fortunate ones, anyway – the Robinsons seem to have realized that they are part of something that is bigger, and more significant, than both of them. As rambunctious as the Crowes could be, they stood for something – and can again. Aptly, the song that fills the room after “Eight Miles High” ends is the Incredible String Band’s “The Circle Is Unbroken,” from the 1968 album, Big Huge, now a freak-folk touchstone. One verse in particular proves resonant:

Seasons they change, while cold blood is raining,

I have been waiting beyond the years.

Now over the skyline I see you’re traveling,

Brothers from all time, gathering here.

Come, let us build the ship of the future.

Lovely stuff, to be sure, but “the ship of the future” has not yet fully set sail, and a great deal of water has flowed under The Black Crowes’ karmic bridge in recent years. In early January of 2002, after more than a decade of commercial ups and downs, personal upheavals and personnel changes, the Crowes issued a terse statement: “The Black Crowes are taking a hiatus. For the time being, Chris Robinson is pursuing a solo career. [Drummer] Steve Gorman has left the band for personal reasons. Stay tuned for news about Rich Robinson.”

During the three years apart that followed, both Chris and Rich made solo albums, and often played with former members and associates of the Crowes, a kind of extended family, with all the complications such relationships entail. Every family enterprise takes on the emotional character of the family itself. With Chris and Rich, who started the band as teenagers in Georgia, sitting woozily on the top of the organization chart, things were far from stable. A dizzying revolving door of members has spun around over the years, with at least a couple coming, going, re-joining and then leaving again. Even since the Crowes regrouped in 2005, guitarist Marc Ford (a former member) joined and then resigned by fax two days before a 2006 tour; drummer Bill Dobrow, brought in to replace Gorman, was canned after a few months; keyboardist Eddie Harsch (another former member) rejoined and later was asked to leave; Rob Clores filled in for Harsch, and then was replaced a year later. In the cases of Harsch and Ford, drug use was a factor in the departures.

Still with me? For now the band’s line-up, and the crew that worked on Warpaint, are Gorman (who, apart from that short stint in 2005, has been with the band from the beginning) on drums, Adam MacDougall on keyboards and Sven Pipien on bass, along with Chris on vocals and Rich on guitar. Most dramatically, it was announced in December that guitarist Luther Dickinson, a longtime friend who had been invited to play on Warpaint, would be joining the Crowes while maintaining his spot in the North Mississippi Allstars.

“It’s a resilient little tug boat, The Black Crowes,” Chris says wryly. “I’m pretty secure with who I am and who we are as a group – and the mistakes we made in our youth, and how we no longer want to make those same mistakes. But, again, it’s always been me, Steve and Rich, and we’ve known Sven longer than Steve. That’s 20 years of knowing and playing music with each other. I’m blown away by Luther’s talent, and, in all truth, it feels as if Adam has always been there. Everyone is more inspired.”

Amid all those changes, and perhaps, in part, because of them, Chris and Rich have not done interviews as members of The Black Crowes since 2001. And they’re not exactly wild with enthusiasm about doing them now. “It is weird that The Black Crowes would cause so much strife and chaos among journalists when we were young,” Chris says at one point. "We were very defiant. And I still feel that we are, because that’s what rock and roll is to me. Guess what? I’m not you, man. I don’t live like you.

“I mean, I haven’t talked with a music journalist in a long time, seven years or something,” he goes on. “We couldn’t have been more apprehensive, because we love our little cocoon that we’ve built. Sure, we got a little angry and crazy with each other, but with time comes change. We started off as teenagers to be in a rock and roll band, and we were very sensitive and emotional people. Just not with each other.”

Since the Crowes regrouped in 2005, they’ve maintained a media blackout, and very much taken all things band-related one step at a time. A few club dates. Some touring. Then recording the new album. The idea was that if the group was to have any chance of surviving, and if Chris and Rich were to be able to maintain any semblance of their delicate peace, potentially hostile outside forces needed to be kept at bay. When they began to talk about getting back together, Rich explains, “We addressed some issues that had come up. ‘Did you say this?’ ‘Did you mean this?’ ‘Did you do this?’ Stuff that was in the press. And with brothers, I’ve found, people like to get involved in drama. Whether it was press or friends or people who used to work for us, there was a divide-and-conquer mentality. We had to clarify some things.”

But with Warpaint completed and a world tour in the offing, the brothers decided – or, more accurately, resigned themselves to the fact – that it was finally time to come forward. In doing so the differences between them were often more apparent, at least on the surface, than what they held in common. Most notably, they did not want to be interviewed together, so each sat down on the same rickety wooden chair in a small, freezing cold backstage room at Angel Orensanz for separate, consecutive interviews. Beyond their choosing the same precarious seat, their personal styles, attitudes and appearances were so starkly contrasted you would need to do a DNA test to determine that they were brothers.

Rich sat hunched on the chair in a grey, pin-striped sports jacket, a yellow Oxford shirt unbuttoned at the collar and blue jeans – preppy dishabille. A white scrim stood behind him, and at one point a maintenance man came in with clattering folding chairs to store in the room. Rich was extremely polite, spoke softly and seemed to want to be liked. But he was wary, clearly expecting the worst. He answered questions as if he’d been briefed beforehand by a smart, but cautious lawyer: Don’t get defensive. Respond to what is asked of you, but don’t go too far. Don’t open up any unexpected lines of inquiry. Don’t raise any unnecessary issues.

For his part, Chris, wrapped in a pea jacket and a gray scarf, draped himself over the chair, rockstar style. His beard and long hair were a freak-flag-flying statement, a point of rebellious pride. “I’ve had people, man, in New York, fucking Kansas City, wherever, they don’t recognize me, but they get angry, in my face,” he says. “Why do you look like that?”

Throughout our conversation, he lights, re-lights and occasionally pulls on a pungent-smelling joint, and sips a Newcastle Brown Ale. Consequently, his answers tend to, well, ramble – unlike Rich’s, which dutifully round off after a reasonable time. He occasionally provides gentle reassurance that he is going to get to the point. In a repeated gesture that simultaneously seems ridiculous and strangely elegant, he folds up the hem of the left leg of his jeans and flicks the ashes from his joint into the cuff. Is it possible that he simply doesn’t want to further defile the well-worn and far-from-clean floor of the Angel Orensanz? Who knows? As he does it, it somehow seems an ingenious thing to do. Only afterwards does it appear entirely purposeless, a kind of absurd, Chaplinesque joke.

But Chris shares little of his brother’s restraint. Asked if he and Rich spend much time together, he’s bluntly honest. “No,” he says almost shyly, before bursting into laughter. "I mean, yeah, on the road, we all still ride on the same bus, pretty much. But I live in hippie heaven in Topanga, California, and he lives in the antithesis of hippie heaven in Connecticut, out by Greenwich.

“But I do know one thing,” he hastens to add. “We do love each other. And I am infinitely interested and impressed with the music that he makes, and that he allows me to make with him. Because it is unique, and it was the fuel that put us out into this weird life. It resonates with people, and that’s a great thing. And we get to do this without having to be people that we don’t want to be. I don’t ever have to pretend.”

The Crowes’ music, of course, is precisely what binds the brothers together, however fragilely. Going “on hiatus” may have been, as always, a euphemism; Chris, at least, was determined never to return to The Black Crowes. But that fight seems in the past now. “When we broke the band up, everybody was going through a lot of stuff,” Chris says. "We definitely weren’t patient. It wasn’t like, ‘Let’s go away from each other for a year.’ It was like, ‘Let’s never do this again!’

“It was dramatic,” he adds, laughing, “because we’re very dramatic.”

The brothers went for a long time without speaking to each other, which gave Rich a renewed perspective on their years together. “Chris and I have a complicated relationship,” he says. "The two of us had never really gotten away from each other. We lived together, and then we were on tour together. So it was time to stop for a while. Like, ‘Live your life, and I’ll go live mine.’ When we first split, Chris really never wanted to come back, and I was okay with that, too.

“But as time goes on, you become less selfish,” he continues. “Sometimes when you’re in that isolated world, it’s easy to take what you do for granted. It’s easy not to see what good you’re doing. Music really is one of the only forces that unites people. You could have four thousand people in a room, or ten, or forty thousand or a hundred thousand in a place enjoying music, and that’s an amazingly positive experience. But if you don’t stop and look at it, it’s easy to forget that. And it’s disrespectful to forget that. It’s disrespectful to the gift, this communal experience that everyone onstage and in the audience is feeling.”

During their time apart, Chris released two solo albums – New Earth Mud (2002) and This Magnificent Distance (2004) – and Rich put out Paper (2004). They toured in various configurations, and, in general, explored the possibilities of life outside The Black Crowes. During this period, Chris was living outside Los Angeles with his then-wife, actress Kate Hudson, and experienced a degree of notoriety that even the multi-platinum sales of Shake Your Money Maker had not inflicted. He and Hudson had a son, Ryder, in 2004, but got divorced two years later amid a blaze of tabloid coverage.

Early on in their relationship, it was speculated that Hudson was a factor in Chris’s decision to leave the Crowes – an interpretation that Rich, who served as the best man at his brother’s wedding in 2000, discounts as immaterial. “At the end of the day, Chris made his own decision,” he says. "Whatever influence Kate had or didn’t have, it was his decision to stop. You can’t blame her for that. I don’t know what she did or said – or if she did anything. It was something he brought to us.

“And as far as Kate goes, they really seemed to love each other,” he goes on. “It definitely brought a different kind of attention to him, and in a roundabout way to the band. But it wasn’t earth-shattering. They seemed happy, and he seemed really hurt when they got divorced. That’s really all I saw.”

Looking back, Chris is philosophical. “It was a hard thing to have your marriage break up publicly,” he admits. “But we both love each other, and love gave us a beautiful child. It was more difficult for the people around me. I don’t read gossip magazines, so I could care less about that stuff. And I don’t watch TV. It bothers me, just as a human being, that my son has his picture taken. I don’t really think he should be used to sell magazines. But that’s just part of life.”

The seed for The Black Crowes’ reunion was planted in 2004 when Chris Robinson was in New York to perform at The Jammy Awards and he called Rich, who was working on Paper at Globe Studios in Manhattan’s meatpacking district. “He said, ‘What are you doing?,’” Rich recalls. “And when I told him I was in the studio, he said, ‘I’ll come down.’” He grimaces as if those were the last words he expected to hear.

“It was shocking,” he goes on. “Musically, he was really excited about what I was doing. So we started talking.” Chris invited Rich to join him at The Jammys that evening, and the two men, along with keyboardist Eddie Harsch, jammed with Gov’t Mule on the Crowes’ anthem “Sometimes Salvation.” As a result of that appearance, requests started pouring in for the Crowes to perform. The brothers began to iron out their difficulties and talk about pulling a version of the band together.

Chris, needless to say, doesn’t recall his visit to the studio in quite those stirring terms. “Yeah, we hadn’t seen each other in a long time,” he says slowly, as if trying to recall the event. “I was like, ‘Do you guys have a bottle of wine or anything?’ I remember being happy. And I also remember understanding that it was probably time for us to do something.”

Why? “Because it’s important to us,” he says. “It’s our story, but it’s a lot of other people’s story too. Our songs resonate with people. And that goes for Steve and Sven and the new guys. It’s hard not to want that energy in your life. As a wellspring, more than seeing Rich in the studio, I remember our sitting around my mom and dad’s house, and he had a Taylor 12-string acoustic guitar, and, instead of playing Bob Dylan or Velvet Underground songs, we started writing our own. They happened to sound a lot like R.E.M,, but they were real songs. That was a long time ago now.”

Reconnecting with that personal history, and the Crowes’ extraordinary experiences and lasting achievements – six studio albums, a tour performing Led Zeppelin songs with Jimmy Page, doing shows with Bob Dylan, Neil Young, the Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones – provided the momentum that carried the band through the next two years. Fans loved the live shows, but for Chris and Rich a crucial element was missing: new material they thoroughly believed in. They didn’t want to put pressure on themselves, but it soon became clear that, for the Crowes’ reunion to be truly meaningful, Chris and Rich would have to write songs together again and the band would have to record.

At first the two men tried to write together, but it wasn’t working. “We attempted to put some tunes together, but they were not something that could propel us to the next place we could go,” Chris says. “Or we were just not getting along. It was hard getting back together. It was nice that people wanted to hear us, and that it was so successful. But it took me up until this music we just made to really be interested in being in The Black Crowes. Even though we were playing out and having fun, I didn’t have a clear-cut picture of the future.”

Rich began feeding Chris tracks for songs he was working on that would become some of the strongest material on Warpaint – tunes like “Daughters of the Revolution,” “Evergreen,” “Move It On Down The Line” and the powerful ballad, “Oh, Josephine,” which Rich calls “my favorite song we’ve ever written.” The band repaired to Allaire Studios in the Catskill Mountains, not far from Woodstock. “When we got into the studio, it just flowed so easily,” Rich says. “Luther came in, and our new keyboard player, Adam, and that was great. The place up there was beautiful. We were on top of this mountain, and we were all living in the same place. There were no city distractions, or people coming by. We were up there to work. A lot of that made it onto the record. Nature – and harmony.”

Warpaint has the feel of an early Stones record – simultaneously loose and relaxed, but intense. It’s the album the Crowes have always striven to make but never quite achieved before. Dickinson’s beautifully expressive slide playing brings a lovely lyrical quality to the album – an eloquent complement to the crunch and swing of Rich’s riffs and the rhythm section’s tension and release. MacDougall’s piano works subtly to emphasize both the grooves and the melodies; his playing is never showy but somehow you always notice it. And without being overt, Chris, in his lyrics and vocals, captures the conviction of a band with nothing left to lose – and its warpaint on.

“The last verse of ‘Josephine’ says, ‘It’s too late to play it safe, so let’s let it all ride,’” Chris says. “I wrote that verse in the studio. I felt that everybody knew what I was talking about – that it was about all of us. There’s nothing to think about any more. There’s no hesitation. This is what we’ve been waiting for. This is what we do now. This is where we go. The only thing we have to deal with now is, do we want it to go away? Do we want to regress?”

The haunting shadow of the battling brothers again? “I never thought that was fun,” Chris says. "It’s just that I’m stubborn and he’s stubborn. But we always found a good place to do the music. To me, this record has set us on a track of real progression. But it’s distinctively The Black Crowes. There’s a lot of strut in it.

“As we move along,” he concludes, “I think authenticity is going to be of great worth to people. I like rooms that are crooked. I like things that aren’t painted evenly. Texture. Nothing should be perfect. That’s true in a lot of realms. And that’s what we are.”