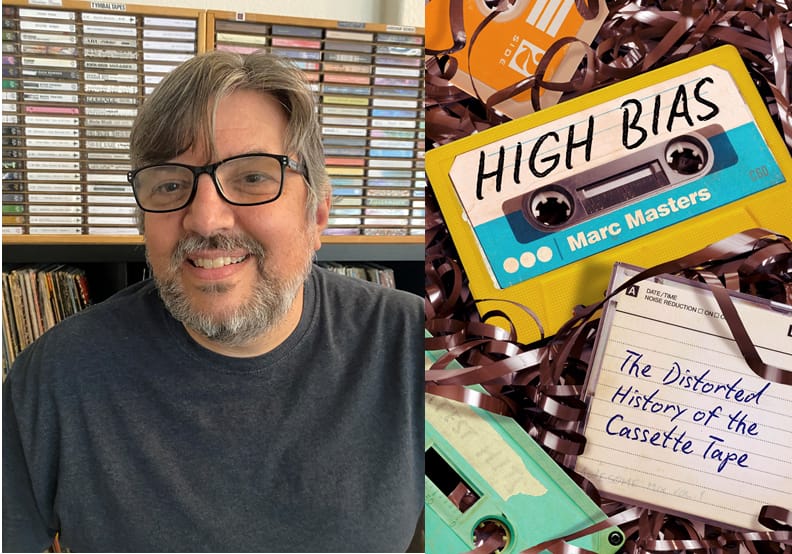

Tape Cases: Marc Masters Unspools the Technological Origins and Cultural Impact of Cassettes

“The cassette tape has meant so much to so many that its history is as diverse as the innumerable people whose lives it has altered,” Marc Masters writes in the introduction to his new book, High Bias: The Distorted History of the Cassette Tape. “What follows is a version of that history, tracing both how the cassette tape emerged—as a technological development, a marketed product, a cultural icon—and how things changed because of the cassette tape. It’s a winding, messy path through international commerce, far-flung musical movements, covert underground cultures, and most important, intimate connections between people obsessed with their own ways of using and sharing cassette tapes.”

High Bias contains plenty of big ideas about a moderately sized item, whose inventor originally carved a piece of wood that he carried in his pocket to assess its proper dimensions. However, this is no stodgy academic monograph, as Masters is a lively narrator, who finds room for Daniel Johnston, the “Home Taping Is Killing Music” campaign, Syrian cassette kiosks, boom boxes, Nebraska, the hip-hop mixtape scene, Awesome Tapes From Africa, go-go street vendors, the current cassette underground and even Dead Relix.

For a number of years, Masters wrote a monthly column at Bandcamp that identified notable cassette releases. This, in turn, led him to explore the subject in longer form. He notes, “Over the past decade, people have started to put music back out on cassette, and I thought there was a unique opportunity to tell people who loved cassettes, but didn’t know they’re back, something about why they’re back. Also, it would let the young people who are into them now find out more about where they came from. I was prompted by a combination of the fact that I had loved them growing up and that there is still something special about them that’s valuable.

“I think the thing that always drew me to tapes, and what’s kept me into them, is they’re the one format that has the most personal aspect and also a slightly subversive aspect. People could use them for so many different personal reasons, like making mixtapes or making their own music on 4-tracks, or trading music with people and dubbing each other’s records. The main thing I wanted to capture about cassettes is how that’s unique to them as a format. Cassettes really made people have more of a personal relationship with their own music or the music they were making or trading.”

Can you recall either the first cassette you bought or the first one where you really came to appreciate the medium?

There’s a dual stream there in terms of when I started getting into them. There was enough prerecorded stuff coming out that I bought some albums on cassette so I could listen to them in my car. For instance, there was a Cure album that had the greatest hits on one side and then a bunch of B-sides on the other side, which you couldn’t get on the record. It was only the cassette that had them on the B-side and I wore that out in my car. That’s one that I always think about—although it was probably not the first cassette I ever got—because it had such a unique aspect to it.

Then in terms of personally made tapes and mixtapes, a friend of mine had a Bowie album and I had a Bowie album and we couldn’t each afford two Bowie albums, so we traded tapes of them. The one he had was Low, and I listened to that a lot on tape—it was a breakthrough album for me in terms of realizing Bowie was more than just the guy I’d heard on the radio.

In High Bias, you note that while the audio quality of cassettes is imperfect, there also can be merit in that.

I can totally understand why cassettes had a little bit of a bad rap compared to vinyl and eventually CD. If you were looking for pristine audio, cassettes were not going to give it to you. But that didn’t bother me. Growing up, I never really knew what the best sounding things were. It just wasn’t on my radar so much. So I was fine with listening to things on cassette, even if they didn’t sound pristine.

Then when I started gravitating toward more experimental and weirdly made lo-fi music, it was a perfect format for that because it added to the mystery and weirdness of the music I liked. So that’s kind of the angle I came at it from.

Also, and this is a separate issue from the sound quality per se, but cassettes also had a bit of a commitment aspect to them. Once you hit play, it’s a pain in the ass to try to figure out how to get to another track or to rewind and listen to a song. So most of the time, you’re listening to a full album, and I always liked that aspect of it. It allowed me to surrender, stop trying to have too much control and just let the artist make a statement through the whole album.

When it comes to cassettes, to what extent would you say that the medium is the message?

You can argue the medium is the message with all the formats. I like all the formats— I’m almost agnostic—although I have a little bit more of a warm feeling towards cassettes. They all had different aspects that made them part of what you were hearing and what you were doing.

However, I do think that with cassettes— more so than vinyl or CD—the way they reproduced the sound, or didn’t quite reproduce the sound, had a lot to do with how you heard it and how people used it. I talk about the indie-rock and lo-fi stuff like Lou Barlow and Daniel Johnson, where you can’t really imagine them going into a studio and playing that music.

It also flipped authenticity on its head a little bit. You would think that for music, or any kind of recording, the most authentic thing is the clearest, cleanest version of what the person played. But often, I would listen to a tape clearly made on someone’s 4-track, and I would think it was more authentic because there’s almost no one between me and the artist except the tape. There’s not a lot of people telling them what to do. They’re making it themselves. There’s typically not labels or producers saying, “No, don’t play that way, play this way.”

So the hiss and lo-fi-ness started to have this weird authenticity to it, which was totally a byproduct of the format. It wasn’t like the artists had much control over that lo-fi or the hiss aspect, but it meant that they probably had done it in a basement somewhere without anybody telling them what to do.

Can you talk about the import of Springsteen’s Nebraska album in this context? As you note, he initially recorded it on a 4-track and then, when he attempted to capture those songs in a formal studio setting, he felt that “the better it sounded, the worse it sounded.”

Clearly, the way he recorded it had a big thing to do with how people received it and how it’s perceived even now. I think if he had made it in the studio and if he’d stuck with the studio stuff, there’d be a different reason to like it, but there’s no way it would have the specific impact that it had.

Most people responded to it in a way that was like, “Wow, we’re getting something more direct from him than we have before.” That’s definitely a function of the fact that he wanted to do it on cassette. He essentially said, “OK, this isn’t the ideal format in terms of how everybody thinks it should sound, but what I want out of this record is happening on this canvas that I’m putting it on, so I’m going to stick with it.”

I’m sure there were people who told him he couldn’t put it out that way, but he was a big enough artist that he could tell them that’s what he was doing.

What can we make of the fact that the word mixtape is still in common parlance and is often used in lieu of playlist?

I think that’s one of the clearest symbols of the fact that the cassette tape still has this cachet of being something that’s cooler than a mass-produced product or something that is only made by commercial entities to sell things. So many rap artists still put out mixtapes that aren’t anywhere close to a cassette tape, but it’s cooler to call it a mixtape.

I’m sure there are some young people who have MP3s of rap mixtapes or streams of them on SoundCloud who don’t even know what mixtape refers to. But it’s still a cool enough term that people would rather use that than say, “Here’s my new rap stream” or “my new rap digital file” or whatever. None of those things have the coolness aspect that the concept of a mixtape still has. It sort of conveys that someone made it for you—that it’s kind of a personal communication, not necessarily a mass communication type of thing.

Do you think something is lost when a person texts a playlist to a loved one rather than creating and hand-delivering a tape?

I think that as with any new technology, there are ups and downs, and it is tempting for someone like me, who grew up with tapes and loves them and has a lot of sympathy for them, to say, “They’re so much better than playlists.” But I don’t know if that’s the case. Obviously there’s convenience—it’s great to have all this music at our fingertips. I would’ve killed for that when I was making tapes for my friends. So there are good things about that.

What’s kind of lost is the personal aspect and the fact that it took some time and effort, so it sort of slowed you down and made you think about what you were putting on. Dragging and dropping is so much faster and you probably are going to do it quicker and maybe not think about it as much. Not to bring up too much of a cliché, but maybe there’s less mindfulness in making a playlist. You’re also sort of beholden to the user interface of these services. It’s all ultimately going to look the same, whereas mixtapes are so personalizable and every mixtape looked different.

Every mixtape was different. You could put a personality in a mixtape that’s really hard to do with a playlist. That doesn’t mean playlists don’t have a lot of utility for other reasons, but I don’t see how they could ever have the kind of personal feel that a mixtape has.

The book includes a discussion of the Grateful Dead taping community, which spurred the creation of Relix. What did you learn about that community?

I knew people who traded Grateful Dead tapes. I knew that there was a whole culture around it, but until I really talked to people who had done it, I don’t think I realized how much of a community was built up around it and how much this was about meeting people and making like-minded friends. It really built relationships. A couple of the guys I talked to, who’ve been tape traders for 40 years, met some of their best friends from going to shows, having taping sessions or exchanging tapes across the country. I think that’s one of the coolest things about it.

One of the moments when I was researching and interviewing that really made me feel, “OK, this is something worth writing about,” was when I spoke with David Lemieux, the Dead archivist. He told me that, when he was a trader, one of his biggest things was he’d come home from high school and hope that there was a package waiting for him. That’s exactly what one of the heavy metal guys said to me. He was like, “I can’t wait to get home to see if there’s a package of heavy metal tapes that I traded through fanzines.”

So you have Grateful Dead and heavy metal, two very different things, yet these guys were still doing almost the exact same thing because the whole point of it was to find people who liked what they liked, and to learn more about the music they liked through other people who liked it, rather than through gatekeepers or publicists. I do think it’s cool that cassettes brought different types of people together in very similar ways.

A lot of tape traders also took their job of adding filler quite seriously. They would utilize the time that was often available on Side B of a first set to proselytize for another band by adding some choice live selections.

I can remember when someone would ask me for the new Minutemen album or whatever. If it wouldn’t fill a side, I put something else on there, like the Meat Puppets, really hoping that they would like it. Then maybe they might ask me for more of that and we could talk about that band, so I’d have another friend who liked the band. I think a lot of people don’t realize how hard it was when you were into certain non-mainstream music to find anyone else who was interested in it.

I can also remember, when it came to sharing Dead tape lists, that there was sometimes something else going on where certain people wouldn’t let you look at their list unless you had a comparable number of shows to share. In addition, there were other folks who kept two lists and you had to earn their trust before they’d pass along the one that contained soundboards, including the famed “Betty Boards.” Do you know of any parallel behavior in other music communities?

I touched on this briefly in the book, but the Dylan fans had a very similar thing going on, especially with unofficial recordings. There’s a story I read about a person who had a tape [that she had made at her apartment in May 1960 with Dylan, when he was a freshman at the University of Minnesota and wanted to hear a recorded version of himself ]. She wasn’t going to let anyone dub it, but there was one time she played it for a well-known fan [the editor of a Dylan magazine] and, of course, the guy had a tape recorder in his pocket. [Laughs.] So I think that’s kind of a parallel.

Hip-hop also had a version of that where certain DJs would only mix tapes for people who paid them. So there was a certain aspect of that there, too.

I could see how people would feel like there’s a downside to that because it’s a little exclusive. But, at the same time, I think there is something neat about the fact that people thought there was something special there and wouldn’t give access to people who they believed might not care about the music in the same way.

Generally, with Dead fans and most fans, people are pretty open to wanting everybody to hear things, but I don’t think it’s so bad every once in a while if there’s a little bit of an inner circle.

One of the most fascinating sections of the book for me was learning about the cassette culture in other countries and the people who would travel to Southeast Asia and the Middle East, scouring for new sounds in cassette kiosks or bazaars. How familiar were you with all that?

I mostly knew about it through the Sublime Frequencies label. I was a big fan of the Sun City Girls, who are behind that label. I knew them somewhat personally, so I was aware they had been going over there and doing that. It still can be done, although less than in the 1990s and early 2000s. Back then, there was so much stuff over there that you could cull through. You could still make plenty of discoveries.

I feel like I got really lucky with that chapter because one of the things that I was worried about with this book is that cassettes had a huge impact in non-Western countries and that had to be reckoned with in a history of the cassette. In a way, they’ve had bigger impact there than they did here, but I didn’t have the budget to travel places or to figure out how to get in touch with people in other countries who are cassette dealers or labels or artists. But luckily, there are these guys who do that.

So telling that story through their eyes was a double bonus because I could talk about the history of cassettes in those countries, but also tell stories about these guys who are trying to preserve it all. Even though the hunting is a sort of collector-y fun thing for them, it’s also a real service to this music that’s going to disappear. You’ll only find it on cassette. It never got to any other formats.

Did you discover any other music scene or community through writing this book that took you by surprise?

I don’t think there was anything that was a flat-out, full-on surprise. But the one thing that keeps resonating with me is I found out more about the go-go scene in D.C. I grew up in D.C., so I knew that music, and yet I didn’t realize the extent to which it got around on cassette. I had seen the bands play, and I bought a few of their records, but I didn’t realize what a community there was around live cassettes.

It was similar to the Grateful Dead scene, except taken to more of an extreme because there were stores where you could go and look through their list of live shows of all the different go-go bands in D.C. and say, “I want this band’s set from this night on that side. I want this other band’s set on the other side.” Ultimately, not many records came out of that scene, so the entire scene was kind of preserved on cassette.

I think that’s super cool. It was this community-oriented scene where everybody was kind of talking through their bands to other people in the community. So these cassettes were kind of crucial to spreading the music around. That was a big surprise to me. I had no idea.

Now that the book has been out for a little while, what sort of responses have you received?

I did a mini-tour of readings and conversations on the East Coast for about seven or eight dates. I knew this was a pretty accessible subject, but while a lot of people have stories about vinyl, I didn’t realize how many people would come out and share their stories about cassettes.

I did all these events in conversation with other writers, and a bunch of them also brought tapes that they had made. I did an event in LA where a guy DJed strictly from new cassettes—he has a cassette label and he knows all the cassette-label people. He actually DJed off a cassette deck.

Then in D.C., I did an event with my friend Jeff Krulik, who made that movie Heavy Metal Parking Lot. He brought all these different cassettes and there was this great moment where he said that in preparation for the event, he had pulled out a box of cassettes from his parents’ house, and there were like 10 cassettes with no labels. He listened to them and it turned out they were interviews with his grandmother from when he was a kid. Then he told us: “I’m listening to the last one and she’s getting into this really interesting thing and then it cuts. I had taped a Kansas album over the rest of it.” [Laughs.]

But everybody had a million things to share about cassettes and some really good memories about them. I almost felt like these were community events where I was having people come and talk about their memories of cassettes. That was really cool, and it made me feel like it replicated what I was hoping to get at in the book, which is that cassettes created community.