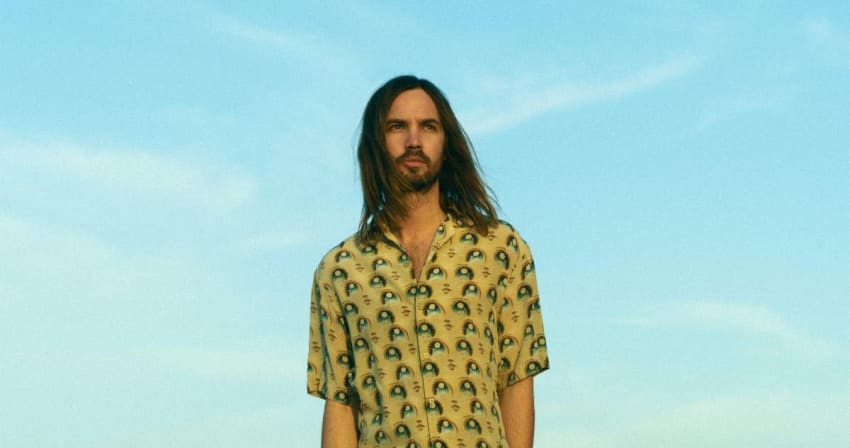

Tame Impala: It Might Be Time

Photo by Neil Krug

With Tame Impala’s 2015 release Currents, Kevin Parker skyrocketed from a self-proclaimed introverted bedroom recording artist to the unwitting savior of arena-sized guitar rock. Now, with that album’s long-awaited follow-up, he’s finally ready to “let it happen.”

Kevin Parker’s Los Angeles home is nestled in the Hollywood Hills, near the top of a steep, snaking road that’s easily accessible from anywhere in the city, yet still feels tailor-made for celebrity seclusion. He purchased the house last year, not long after area fires forced him to evacuate one of the Airbnbs he was using to finish The Slow Rush, his first Tame Impala album in half a decade—and first since he skyrocketed from a self-proclaimed introverted bedroom recording artist to the unwitting savior of arena-sized guitar rock.

“If a fortuneteller told me that was going to happen, I would have asked for my money back,” the 34-year-old Australian singer/ multi-instrumentalist/producer says, sipping a beer on his patio, which is perfectly positioned to offer an unobstructed view of the Santa Monica Mountains’ iconic Hollywood sign.

“[From our first New York show] at Pianos to Coachella last year, it has been this slow mutation from this very small thing into a headlining beast. It was sometimes in my control, and other times, it gradually became bigger than me. There was never a point where I stepped back and decidedly changed its nature, but I want to do that this time. I’m just not sure how to yet.”

These days, Parker estimates that he divides his time “about half and half” between LA and Perth, where he started recording under the Tame Impala banner just over a decade ago. Last year, he married Sophie Lawrence, who he has known since he was 13—he notes that she bought him the fitted shirt with neon hues that he’s currently wearing. He’s ready to embrace his new domestic life, though he jokes that his extended relatives keep “threatening” to visit him at his new pad.

During Tame Impala’s festival sweep after Currents, Parker wore his artist-credential bracelets throughout the season, like slowly accumulating ski tags on a winter jacket, but he’s long since cut them off. “That’s lame,” Parker says with a wry smile. “I didn’t realize everyone did that when I was doing it. That novelty wore off a long time ago.”

His spacious new lair is outfitted with storybook glass windows that offer breathtaking views of the city sprawl. But several of the common areas are still unfurnished, aside from a few essential items and some stray gear.

He’s also put together a home studio, which he describes simply as a bigger and better version of DIY setup that he’s always used to record his music. “That’s the golden scenario, when it’s just me and I’m in a room full of versions of myself,” he admits somewhat sheepishly. “Someone is dancing around the studio, someone is the studied producer, someone is the zonked-out vocalist in the corner thinking of the melody. I’ve always thought about doing a film clip where it’s just me playing all the instruments, but I’ve never been able to stomach the self-indulgence.”

In a few hours, he’ll head back to Perth—his bags are already packed and sitting near a speaker in the mostly empty living room—where bushfires have tragically wreaked havoc on his community and endangered the local wildlife. Aware of his newfound influence, he’s also taken to social media to encourage his fans help those affected by the disaster.

While in LA, Parker met with his production designer to work on the visual elements of his upcoming tour in support of The Slow Rush. And, though his live band will feature most of the same running buddies who have backed him since the beginning, he’s hoping to switch things up this time.

“I’d be lying if I said that it didn’t feel like a completely different show or experience, because it is,” he says. “Some people would probably be upset to hear me say this, but almost no aspect of our show now bears resemblance to when we started. The lights, the sound, the music—me.”

He trails off into laughter, before adding, “I probably look the same, although I didn’t have a beard back then.”

Producer Mark Ronson, one of Parker’s closest musical collaborators outside his immediate Perth circle, has been a fan since the first Tame Impala EP and has seen his friend grow naturally into his rock-star persona.

“Kevin has come out of his shell,” Ronson says a few weeks later. “I saw some picture of him the other day—he was in a car with his shades on looking very cool—and I was just psyched for him. It’s something he may not be thrilled about, but it’s like, ‘Dude, you’ve earned the right to embrace that.’ It’s not like, all of a sudden, he became an arrogant Get Him to the Greek-level asshole. It’s not even that he’s shy; he’s an introvert who has a nice nature. Everything about the way he’s built a career is real—like, ‘This is who I am.’ One time, we did a show and he told me: ‘This is the first time I’ve worn shoes onstage.’ People really adore and worship him. He could be the biggest asshole in the world, but he’s not. The way that he’s managed to keep his shit… if people loved me the way they love him, I’d be a much bigger asshole.”

The time feels right to embrace both those stadium-theatric heights and the rock-and-roll fame that has haunted Parker for the past few years. Earlier on this January morning, Bonnaroo dropped its 2020 lineup, with Tame Impala sharing the proverbial top line with psychedelic-metal pioneers Tool and indie-approved pop star Lizzo. Bryan Benson, who books the festival as part of the AC Entertainment team, describes Tame Impala as that “core Bonnaroo” band who fits comfortably in the middle of those welcome extremes.

All across LA, the excitement is palpable. A coffee shop is playing one of The Slow Rush’s multiple singles, a synth-driven slow-jam called “Lost in Yesterday” that opens with the telling lyrics: “When we were livin’ in squalor, wasn’t it heaven?/ Back when we used to get on it four out of seven/ Now even though that was a time I hated from day one/ Eventually terrible memories turn into great ones.”

On the influential alternative station K-ROCK, a DJ is bumping “Elephant,” a Black Sabbath-leaning showstopper from Tame’s sophomore album Lonerism, as a way of explaining how they’ve jumped from indie-darlings to big-name rockers, while still steering mostly clear of the Hollywood glitz. When Tame Impala closes out Bonnaroo’s main What Stage for the first time in June, they will have also pulled off a Grand Slam-like victory lap headlining the longstanding “top four” U.S. music festivals. (The band headlined Coachella, Lollapalooza and ACL in 2019.) But, this time, Parker is returning to Manchester, Tenn., with some unfinished business.

“I didn’t realize that the set we played was expected to be this special show that lasted two hours,” he says of their 2016 late-night spot. “Afterward, people said, ‘Oh, you’re finished?’ And we were like, ‘You want us to play songs we haven’t played in 10 years?’ I was a bit disappointed that nobody told us, because we probably could have played for two hours. So I wish I could apologize to the people there.”

Parker, as is his wont, created The Slow Rush entirely on his own—from the instrumentation to the production and the mixing—beginning during the summer of 2018. At the time, his fans were already clamoring for another album.

“I didn’t know when I’d make another Tame album,” Parker says. “I thought it was quite possible that I’d never do another one. I resigned myself to that. I got three albums; that’s a trilogy. Some great artists only have three albums. Some have one. A bit of my rebellious spirit was also kicking in there. The fact that I knew everyone wanted one made me dig my heels in even more, like, ‘Fuck you; I’m not making one.’”

The rumor mill really kicked into gear in early 2019, when Tame Impala were booked for Coachella, nabbing a prime Saturday night headlining spot after Justin Timberlake bowed out. Parker released two singles, “Patience” and “Borderline,” that seemed to foreshadow The Slow Rush’s sonic template, with their inviting mix of lush R&B and stoner psychedelia. Yet, despite playing Saturday Night Live and announcing Tame’s first stateside arena shows, a release date never materialized.

“I consciously wanted to rush it to get it finished for all of those shows we had booked,” he said. “Progress was going so fast at the end of 2018 that I was like, ‘There’s no way I’m still going to be working on it in March or April.’ That was only because I got the easy stuff out of the way, and the difficult stuff was yet to come. I forgot how much mental sacrifice—how much time sacrifice—it takes to finish an album, especially an album like this. Each song is quite long and quite layered. At the start, I wanted an album that was like brush strokes. But by the time I got halfway through, I knew it had to be something more considered.”

It was worth the wait. The Slow Rush is both a continuation of the more soulful, groove-oriented textures that Parker explored on Currents and a return to the meditative darkness of his earlier, guitar-driven releases. It’s a headphone record that can also seep into the background of a bar or restaurant. And that’s now an important concern: Though it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when, during the five-year lag between Currents and The Slow Rush, Parker had his Sword in the Stone moment, emerging from the ether to become a major player in the pop world. He’s collaborated with the likes of Kanye West, Lady Gaga, Miguel and Gorillaz; heard Rihanna cover “New Person, Same Old Mistakes” on 2016’s Anti (the track was retitled as “Same Ol’ Mistakes”) and listened as Beck has name-checked him as a modern influence.

In addition to getting married and moving to the States part-time, he’s also watched as the indie-rock community that nurtured him has gradually matured into the new festival mainstream—and seen major-label divas enlist DIY musicians to help steer them toward something more authentic.

“All of those things coming together is what really informed the message of this album,” Parker says, noting The Slow Rush’s cover, which captures the sands of time spilling out of an illuminated window. “That includes getting married. As with all of my albums, I’ll write a passage and then, almost instinctively, I’ll sing about what that makes me think of. With Currents, that was personal development, in the form of severing a relationship or ties with your old self. This time, I suddenly woke up and realized that it’s been 10 years since all this started. With a lot of these songs, I got a sense of this romantic, strange, nostalgic, scary feeling that time has passed.”

***

Parker was born in Sydney, but grewup in Western Australia. He had a rocky early childhood—his mom and dad split up, reconciled and broke up again—and he and his brother were separated between their parents for a while.

His family exposed him to music at early age—he says his dad, who played in a band part-time, listened to “the usual diet of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys, Fleetwood Mac and Supertramp,” while his mom’s tastes veered slightly more toward the eclectic. Even as a child, he was fascinated by the power of melody.

“My real rebelling in life was completely non-music related,” he says with a laugh. “The first music I got into on my own was grunge and metal; it gave me this energy that I hadn’t felt before.”

Parker enrolled at a university, even studying astronomy for a bit, and moonlighted as a law clerk, but his art always remained a primary focus. He started playing in bands when he was a teenager, forming a lifelong bond with musicians like Dominic Simper, who remains in the live version of Tame Impala to this day. He also began using songwriting as a way to embrace the loneliness he felt both because of his confusing home life and his introspective personality.

“People always ask me what it’s like to work alone and, honestly, when it’s 3 a.m. and I’m deep in the process, I feel like I’m in a room full of people,” Parker admits. “I have great conversations.”

As a teenager, Parker gravitated toward psychedelic-era acts like Jefferson Airplane and Cream—collecting Doors bootlegs and exploring the prog-rock movement that blossomed out of that period. Eventually, he formed the proto-Tame project The Dee Dee Dums and started playing guitar and then drums in the popular local band Mink Mussel Creek, with other future Tame touring members.

By the mid-2000s, Parker was also sharing a dorm-like setting with a number of his bandmates and fellow musicians; he’d sculpt Tame songs in his room upstairs while his friends rehearsed downstairs. “We’d work on a track and have a spliff—we were just having fun,” Parker says. “It was almost as though the music was the medium for us to enjoy each other’s company. We were so socially awkward that we needed something like music to be the platform. We couldn’t just sit around and talk about our feelings or chicks.”

From the outside, Perth often seems like ground zero for the current psychedelic revolution, thanks to interconnected bands like Tame, Pond and GUM, but Parker is quick to dispel those myths.

“There really wasn’t a psych-rock scene in Perth,” he says. “It was just our little shared house. There was heaps of music being made in our community and we’d play on these six-band bills, but in terms of any psych-rock scene, it was a total of 10 people.” They’d listen to vinyl records together and, though Parker says that Tame didn’t absorb everything he was listening to, that experience altered his sonic outlook.

“It was extremely fertile, both because we were so comfortable being around each other and being creative, and because we had a bit of that sibling competitiveness,” he says. “We’ve never spoken about it or acknowledged it, but it was definitely there in the healthiest way possible. We never wanted each other to do badly, but all I wanted to do was make music that was as good as the music my friends were making because I respected what they were doing so much. But as much as people say, ‘We’re all friends and we love each other,’ there’s something to be said for having that healthy competition. That shit is vital; that’s why people talk about scenes in music.”

While Tame Impala has never quite felt like a nom de plume, it’s never been a true band either. Parker has always recorded almost all of the group’s music himself—with some minimal assistance from longtime Tame touring member Jay Watson early on—and assumed responsibility for the project’s vision.

As Parker slowly crafted Tame’s panoramic sound, he also assembled a live act, which quickly picked up steam. In 2008, Modular released Tame’s self-titled debut EP, which included the fully realized favorite, “Half Full Glass of Wine.” Two years later, the Australian label dropped his full-length debut, Innerspeaker, a lo-fi mission statement that introduced several of Parker’s original hallmarks: charging guitars, melodic hooks and a fuzzy psychedelic swagger.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., especially sections of Brooklyn, N.Y., a contemptuous psych-rock boom was playing out at a network of semi-legal venues, with a wave of new artists combining a punk-rock aesthetic and a post-jam sensibility into a sub-genre of their own.

“It seemed like most of these acts hopped around, playing shows at Death by Audio and Monster Island/Secret Project Robot,” says PopGun’s Rami Haykal, who booked Tame Impala’s first Brooklyn gig at the art-rock incubator Glasslands in 2010. “Programmingwise, it seemed like this period lasted between 2008 and late 2011. Right around 2012, we definitely saw a change in the kind of touring acts playing Williamsburg.”

Like many, Haykal first heard about Tame Impala through MGMT, who were the modern psych-world’s shot heard round the world—the band who proved that trippy guitar rock and infectiously danceable synth-pop didn’t necessarily have to be strange bedfellows, and that high-fashion had a seat at the DIY table, too.

Tame Impala’s 2012 follow-up release, Lonerism, cemented their reputation as a blogger buzz-band and hinted at a world outside those share-house sounds on the dreamy “Feels Like We Only Go Backwards” and the infectious “Elephant.” Parker earned accolades for his adventurous guitar playing and quickly ascended through the venue ranks.

“Williamsburg was still affected by the [economic downturn] until around 2011-2012,” says Haykal, who continues to navigate a similar mix of indie, psychedelic and electronic acts at his club Elsewhere. “There was a lot of stalled construction. But then, things started to pick up again and you could see an influx of people coming into the area and checking out [this music]. You really noticed it in the spring—people were more willing to venture into the area.”

Parker wasn’t the most unlikely musician to emerge as the face of the new psych-rock revolution. His natural, tall, thin frame and long flowing locks are right out of Almost Famous, and his voice has a similar cadence to the original psych-rock pop star. (“So it turns out the reason I sound like John Lennon is [that] I have Bilateral Sinonasal Disease! Finally, I have an answer!” Parker humorously posted on social media a few years ago, along with an X-ray of his nasal passages.) And even at his most experimental, he was never afraid to include some tasty earworms.

The hip-hop world took notice as well. Parker says that A$AP Rocky was the first rapper to reach across the aisle, contacting him shortly after the first Tame album. But the frontman says, “I didn’t do much outside my own bedroom, so I barely answered the call and shut that whole thing out. But because I’m friends with Mark [Ronson], I was able to let my guard down with him.”

Ronson first bonded with Parker while on the road. As their partnership developed, the star producer recruited Parker for some of his Uptown Special shows. And, Parker gave him a few songs for his 2015 album of the same name.

“We got to know each other and he played me some demos for Lonerism, wasted in the hotel room,” Ronson says. “[Another time], we were hanging out, again a little wasted, and he turns to me like, ‘We should do some funk, just you and me—bass lines and instrumentals.’ This was way before [I co-wrote] ‘Uptown Funk.’”

While working on Ronson’s Uptown Special LP, Parker passed him some ideas that ended up surfacing on Currents. “He sent me a demo for ‘’Cause I’m a Man’ and I thought, ‘I don’t know if I have a place for a down-tempo, meaningful song,’” Ronson admits. “But he wrote back two days later like, ‘My band thinks I should keep that song.’”

Ronson also got a sneak peek at “The Less I Know the Better” during a late-night jam session with two of his cohorts, musician/ producer Andrew Wyatt and producer and former Lettuce keyboardist Jeff Bhasker. “He was working on a bass line and workshopping it in his head,” Ronson says.

Parker’s blank-canvas approach seemed to culminate on Tame Impala’s third record Currents, a decade-defining album that managed to wrap the era’s biggest trends—kaleidoscopic R&B, bass-heavy party funk, Kraut-rock repetition, hip-hop beats, indierock melody and heady psychedelia—into something completely original. Tracks like “Yes I’m Changing,” “Eventually” and “’Cause I’m a Man” placed newfound emphasis on Parker’s vocals, and much of the record toned down his guitars in favor of synthesizers and rhythmic pockets.

The LP was an instant success, reaching near the top of the charts, and the band hit the road for a never-ending mix of theater and festival appearances.

And, as dance, rap and pop started to dominate the live-music circuit, journalists started to brand Tame Impala as the rare guitar band capable of anchoring a major festival.

As his profile increased, Parker also tested out the hip-hop waters with people like Travis Scott, who snuck the Tame Impala lead into NBC’s Studio 8H for an unannounced appearance during his SNL taping. “John Mayer was next to me with equal anonymity,” he says, as he describes the surreal jam session and perhaps his own ability to genre-jump with the ease of the Dead & Company guitarist.

“I love the idea of putting something out there that no one else knows is mine except for me,” Parker says. “After being somewhat in the public eye, that is more enticing than ever.”

Yet, when the question of a new Tame album surfaced, he remained mum.

“There was no decision; I just didn’t want to [record],” he says. “I’ve never sat down and forced myself to start writing a Tame Impala song. I believe whole-heartedly that if I had gotten started any sooner than what felt natural, it wouldn’t have come out naturally; therefore, it wouldn’t be as inspired. Especially since there was a bunch of other stuff that stole my ambition, stole my attention from working on a Tame album. But there’s something that working on Tame Impala music gives me that nothing else can.”

And, a major part of that creative rebirth was finally admitting to himself that he could bring everything he’s learned since Currents back into the Tame Impala framework.

“It was realizing that Tame can be anything,” he says. “But more specifically, it could be all of the things that I assumed it couldn’t— my love of hip-hop, pop or house music. I always assumed that stuff would have to stay an arm’s length from Tame.”

When Parker decided to start work on what would become The Slow Rush, he says he left the door open mentally for a more social recording situation—bringing in either “the other guys in the band or people I admired.” But he ultimately decided that it had been long enough that he could do it on his own once again.

The basis of all the album’s songs came to Parker during roughly a six-month period starting in the summer of 2018. He worked solo in Perth and Los Angeles, often renting different Airbnbs for a few days at a time. “In many ways, the process of making an album is totally different now but, in some ways, it’s the same as it was when I was 15 years old,” he says. “The first step to it not sounding like a regular rock band is just that it isn’t a regular rock band. It’s perfectly feasible that there are more drum tracks than there are guitar tracks. I’m able to see that in a more abstract way these days.”

“He’s one of the top five best drummers out there, as far as a drummer who is playing beats,” Ronson says. “That’s why a lot of hip-hop people are drawn to his music.”

Throughout those deep studio sessions, a secret mission was to create tracks that could be played by a DJ at a club.

“As absurd as that sounds, I want my music to exist in that world, without it being that,” Parker says. “Because I’ve gotten more confident with the way I can process my drums, every song on this album has real drums. It’s a challenge to make it sound like house music or disco music without using all those elements. It’s the same with synths—they’ll always give you this powerful, direct, futuristic sound.”

Those twists are immediately apparent; “Borderline” contains a haunting keyboard line ripe for a dance-floor sample; “It Might Be Time” has a post-punk spookiness that feels akin to the Stranger Things theme song and “Posthumous Forgiveness” is a synth showcase that explores Parker’s relationship with his father. Parker says that the hip-hop and pop production world was always something that he “had almost God-like respect for.”

For a burst of inspiration, he screened Justin Timberlake’s Justified: The Videos. “If I was stuck on something, I’d be like ‘What would Pharrell do?’” he says of the producer’s work alongside Timberlake. “With the song ‘Breathe Deeper,’ I was imagining that I was in that documentary, making that song.”

During one hazy night of recording in LA in late 2018, a fire blazed through an area where he was staying. He quickly evacuated his Airbnb with his prized ‘60s wooden Hofner bass and his laptop. A bunch of his gear was destroyed, but Parker puts it in perspective, calling the experience more of “an annoyance and an inconvenience” that set him back a week. “There’s probably a song that would have been on the album but isn’t because of the fires, which is funny to think about,” he admits.

Parker continued to tinker with The Slow Rush throughout 2019, without writing any new material. Oddly enough, the sole song that did get bumped, “Patience,” was one of the only hints at what the album would sound like. He says that including the single would have pushed the record over an hour—and he also seems to relish the prankster move of cutting one of the LP’s his most prominent teasers. “I originally wanted to make the album exactly one hour long and call it One More Hour,” he says. “It could be that the whole album is an hour, which is the last hour in someone’s life.”

In August, Tame Impala played New York’s Madison Square Garden for the first time, packing two shows and attracting an audience that not only included a welcome mix of record-store-collecting hipsters and hippie-leaning festival-goers, but also young music fans attending their first big rock concert without their parents. Fitting for one of the first bands of the Glasslands generation to headline MSG, they opened with the extended, through-thelooking-glass-like journey “Let It Happen.” It was Parker’s first time at the famed sports arena; he cracked a joke onstage that didn’t quite stick the landing.

“No one ever laughs at my jokes,” he says. “I literally thought it was a garden, like Central Park.”

But from his banter to the technical aspects of his still-trippy stage show, Parker has learned how to be both an introvert and an engaging frontman.

“There’s no crossover between being a shy social person and being a headlining festival performer,” he says. “No part of who I really am, personally, feels like it’s being challenged by being that person onstage. I’m still terrified of speaking to the audience between songs. The bigger the audience, the more simple you’ve gotta be, but that’s something I’ve learned to adjust to. In fact, it was a relief when we started playing big shows because it was easier to be that character. Playing for a small room actually feels more like a social thing than playing an arena. The bigger the shows got, the more fun I started having.”

Looking ahead, Parker hopes to cut back the lag time between Tame albums. “My next album is going to be brush strokes and elemental,” he says. “I’m always recording voice memos. I’m at that stage where I’m writing a lot of different stuff. I have no idea what form it will take. That’s a state I relish—rapidly scrolling through my mind, thinking, ‘Is it a throwback ‘70s Diana Ross disco hit, something I can give a young pop artist or can it be Tame Impala?’ Its destiny isn’t predetermined.”

In certain ways, modern technology has also brought the radio world closer than ever to Parker. “I dreamt that it was possible for someone who made their album in a bedroom to be able to fulfill their dreams,” he says, mentioning multi-Grammy winner Billie Eilish. “I was told very early on: ‘It’s cute that you want to do this by yourself. When you want to take it seriously, give us a call.’ I reveled in that because I was confident and a brat at the same time.”

And, as his star continues to rise, that mix of introspection and confidence will continue to guide Parker as he navigates the full spectrum of Tame Impala’s possibilities. “I want to blur all these lines even more,” he says. “If we’re headlining a festival, I want to do that to its full potential. But I want to do it right. I want to do everything, but on my terms.”

This article is the cover story for the March 2020 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more subscribe below.