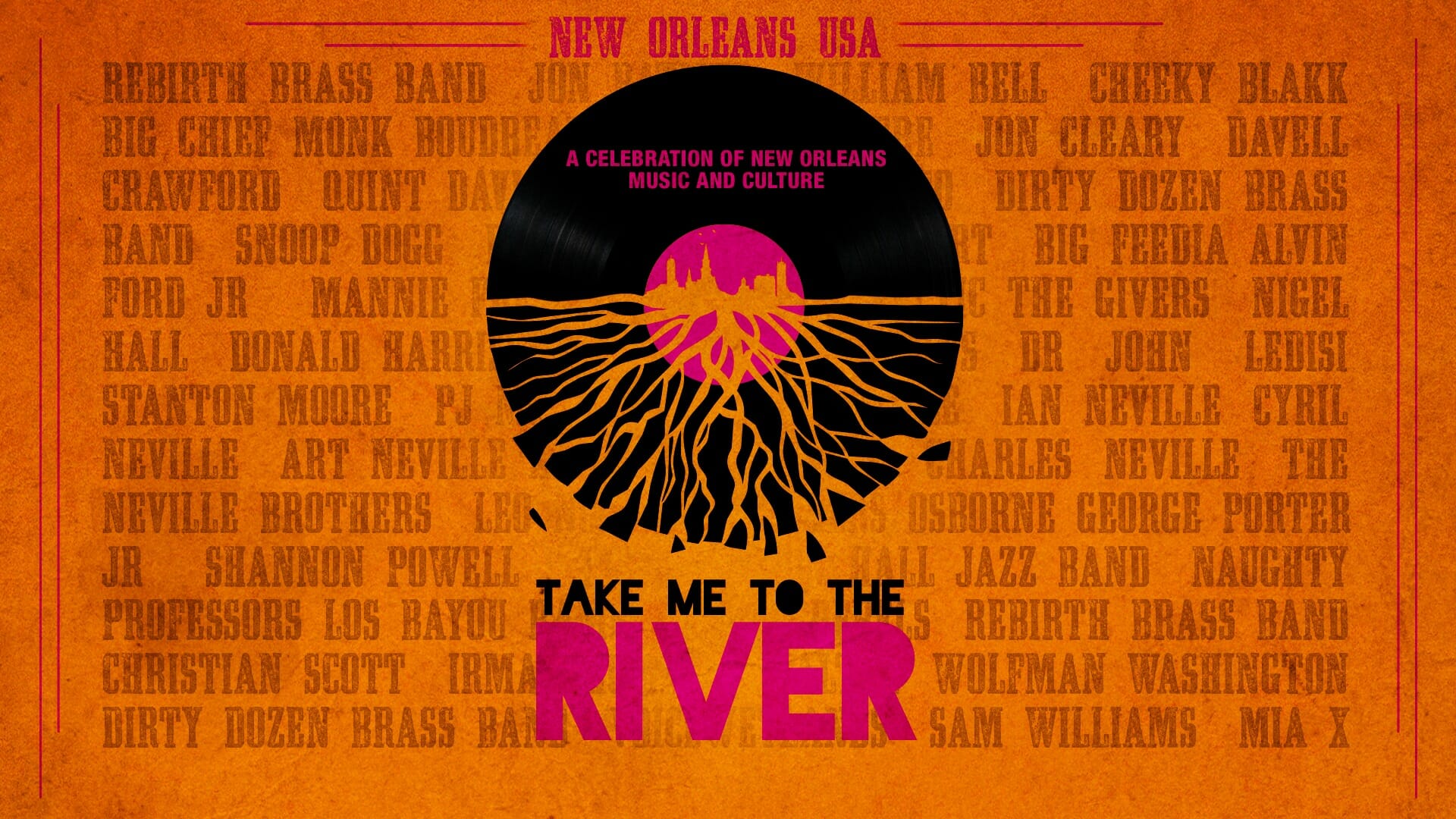

‘Take Me to the River: New Orleans’ Director Martin Shore on the Syncopated Heartbeats of the Crescent City

“The story of New Orleans is a very big one,” says Martin Shore, the director of a new documentary about the Crescent City. “So to present it in an hour and 45 minutes was quite a feat because it’s so rich and there’s just so much in the history.”

However, as anyone who has seen Take Me to the River: New Orleans can attest, Shore certainly was up to the task.

The director was well-suited to build a narrative that blends social, cultural and, of course, musical history. Shore began his career as a drummer, touring in his early 20s with Bo Diddley and also working with Albert Collins and Bluesman Willie. He would then go on to serve as a film producer and music supervisor, before charting a new course by helming 2014’s Take Me to the River, which explores the sounds of Memphis. That documentary was named Best Film at Raindance London and won the Audience Award at SXSW.

Take Me to the River: New Orleans, which is narrated by John Goodman, presents archival footage of the city’s notable denizens, but really hits its stride through a series of conversations and recording sessions that cross generations and genres. These include Irma Thomas, Ledisi, George Porter Jr., Eric Krasno, Ian Neville and Ivan Neville; Dee-1, Mannie Fresh, Big Freedia and Galactic; Donald Harrison and Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah; Dr. John and Davell Crawford as well as a Neville Brothers reunion, captured prior to the passings of Art and Charles Neville.

Shore is also the founder of the Take Me to the River Education Initiative, which is an important nonprofit resource now that music is fast disappearing from public schools. He has also assembled a series of live shows and tours built around the artists in both films. As of February, he is also a Grammy-winner, as “Stompin’ Ground” from the Take Me to the River: New Orleans soundtrack was named Best American Roots Performance.

A live show recorded last year in celebration of New Orleans and Memphis music featuring Luther Dickinson and Cody Dickinson, Robert Mercurio, Ian Neville, Big Chief Monk Boudreaux, Big Chief Bo Dollis Jr., Anjelika “Jelly” Joseph and others, will begin streaming on FANS, this Thursday, September 28 with proceeds supporting the Take Me to the River Initiative.

At what point during the making of your Memphis film did you begin thinking about following the Mississippi River down to New Orleans?

About halfway through Memphis, I knew that the story of New Orleans had to be told. The story of Memphis and the Mississippi Delta is the story of where American music came from and what inspired the world’s popular music. New Orleans had a similar beginning that parallels Memphis and the Mississippi Delta songs of the field. However, its trajectory was formed by influences from all over the world because if you wanted to come to this country, New Orleans was your entry point well before Ellis Island.

All these elements were inherent to the city, starting way back with the initial slave trade. The rhythms coming out of Africa fused with Haitian syncopation, Afro-Cuban music, the habanera and tresillo. So you had this interesting fusion combined with European military marching beats. That instrumentation became part of second line and formed the first world music.

The story of how New Orleans music influenced and inspired popular music was really from a world perspective, as opposed to the very defined Mississippi Delta region.

Can you recall the first time you visited New Orleans and what sort of impact it had on you?

Yes, that’s ingrained into my brain. I was playing with Bo Diddley at the time and we had a day off to go and experience the city. I remember meeting a friend who was from New Orleans and going to Tipitina’s. At that time, the upstairs was limited—it wasn’t exactly the way it is now. I remember walking into Tipitina’s and hearing music that I had heard a couple times in my life but never live, never with that energy and never with everything surrounding that energy—the dancing and the interesting way people moved.

It was zydeco—Clifton Chenier and the Red Hot Louisiana Band. I remember my jaw dropping and having an amazing evening.

Is there something particular about New Orleans that speaks to you as a drummer?

Absolutely. That’s why, in the film, I made a point to have a session of just the drummers [Herlin Riley, Shannon Powell, Alvin Ford Jr., Terence Higgins and Stanton Moore]. There are no drummers in the world like New Orleans drummers. It’s hard to put ratings on art and music, but they’re the most versatile and practiced. They perfect their craft.

To be called a New Orleans drummer is a badge of honor, and it’s not given out lightly. The New Orleans drummers have their own style—each of them has a slightly different style, but it’s all rooted in the same fundamentals. They have so much at their disposal, way more than traditional drummers and even the greatest traditional drummers that you can think of. They can pull from so many different places.

They’re never at a loss to be creative within what they’re playing, and the rhythms of New Orleans are so unique. It’s definitely not on the one, and it barely gets there before the two. It’s got its own sort of syncopated heartbeat, where it makes the people dancing move differently. It makes people listen differently to the music. It’s just totally unique.

Thinking back to the original Take Me to the River, what prompted your move from working musician to full-time filmmaker?

It was an epiphany. I was working at Zebra Ranch with Jim Dickinson, Cody Dickinson and Luther Dickinson.

As most everyone knows, Jim was a great producer and a great keyboard player, musician and arranger. We were working on some music for a film when I took a break and walked outside of the studio on Jim’s property. It was a hundred degrees and humid, as it is in Mississippi. [Laughs.] Jim loved decaying art so you would see all these weird weeds and trees growing through cars and all kinds of stuff. It just came over me. It’s almost like it came out of the ground and through my body that the story of where American music came from had not been told properly. It needed to be told so that current and future generations would be able to readily identify their own music and how that music developed.

I felt that the best way to tell that story, so that the current and future generations could relate to it, was to get our legacy master musicians together with younger stars and make new music. That way, it would be fresh and important and current, but also tell the story and fuse generations together.

So that became kind of a mission, although it took a couple of years for it to come to fruition. I went back and talked to Cody about it right away, and we continued to talk about it over the next couple of years.

Then, in about a 15-month period, we lost Isaac Hayes, Alex Chilton, Willie Mitchell and Jim Dickinson. That was the call to action.

Memphis and New Orleans both are places that have maintained an indigenous music culture despite the forces of homogenization. What do you think accounts for that?

They’re different, but to your point, there are also similarities in terms of the cultural context. With Memphis, there had been a fracture in the community, and it was important to bring that back together. Take Me to the River spoke to that. It’s demonstrated in the first session when we go to Zebra Ranch— that’s where the first session of Take Me to the River, now referred to as Take Me to the River: Memphis, took place. We got Booker T., Al Kapone and the North Mississippi Allstars together, and we recorded. Through our conversation, Al and Booker figured out that they had grown up two or three blocks from each other, yet Al had no idea about his own neighborhood’s musical history. When he grew up, Stax was just a little historical placard. The history and the significance of that history had been fractured, at least temporarily. So our work was to first try and bring that community back together and familiarize everybody with each other again, which was a really fun and exciting time.

In New Orleans, that community has always maintained its heritage, its legacy, its history, and held on to it tightly. In New Orleans, existence is tough with the weather and harder conditions. Their culture, history and legacy are all passed down through neighborhoods and families. These are all held dearly and strongly.

As demonstrated in Take Me to the River: New Orleans, there was a definite difference pre-Katrina to post-Katrina in the way that the culture was disseminated and the way that the community was changing. But that’s in keeping with the history of New Orleans, which is forever changing. It’s always taken on the challenge of change, whether that be weather-induced or people coming from different places or the occupation—it has changed depending on who was in control of that area. The Haitian slavery revolt changed the face of the city. Then, when slavery was abolished, that obviously really changed things.

So it’s been evolving and changing for a long time. But the cool thing about the people of New Orleans is that they’ve held on to what they feel is extremely important. I feel that everybody there knows that it needs help, support and for people to pay attention.

In New Orleans, that’s a point of pride. It also has to do with a lot of smaller groups that are very strong and very dedicated not only to the city, but also to their community. Whether it’s the different krewes that put together the Mardi Gras floats, the balls and the societies or the pleasure and social clubs, there is a strong connection to that culture throughout New Orleans. There’s also the Indian culture, which is a very strong culture. Then you have the musical community, which is another very strong culture.

My plea to everyone is to go to New Orleans and experience it yourself so that you understand how lucky we are to have a place like New Orleans in our country, and how lucky the world is to have that piece of culture coming to them in the form of music, cuisine and other cultural aspects.

There’s something about New Orleans that sparks a certain sense of connection when people visit for the first time. It’s hard to define the nature of it, but I’ve seen that happen time and again.

Maybe what you’re pointing to is a connection you get because you can feel the love and dedication to who and what they are. It’s not hidden. It’s something that they’re proud of, and they want you to see it. They want you to experience it. They’re not holding onto it and being proprietary. They want to bring you in, and everybody wants to be part of the community because the definition of community is fellowship. When you go to New Orleans, they want you to feel that. They want you to feel as if you went to church or had a special spiritual experience. That’s why it’s so important for people to go and experience it.

I do think that in both New Orleans and Memphis, there is a spirit that emanates from the ground itself. The history and the struggle is real. That spirit is still there, and you feel that too.

Part of it is also that it’s really the most northern point of the Caribbean. So the weather feels different, the wind feels different. It also makes you feel like you’ve arrived someplace else, which opens you up to everything I just mentioned.

While you no doubt love the film as a whole, is there a particular scene or session that still gets to you, no matter how many times you’ve watched it?

The session with Irma and Ledisi still raises the hair on the back of my neck. The Neville Brothers session is very emotional for me—it’s still hard to watch it, even though I’ve watched it hundreds of times. I also get that same sort of feeling when I see Dr. John and remember the time that we spent together and how much fun that was—that hits a heartstring for sure.

There are so many great moments that have wonderful back stories to them. I never tire of the end of the film with Snoop, G-Eazy, Cyril, Ivan, Ian, George, Terence Higgins and Big Sam. It’s a very fun song and a very fun session. I enjoy seeing all those folks come together and collaborate.

It’s funny because as you get further removed from the day-to-day work on the film and the intense screening circuit, it definitely hits you stronger and harder.

Speaking of that final scene, as you were recording the sessions, did you have a sense of how the narrative would flow or did that come together in the editing room?

The narrative of the film is obviously challenging because we were covering so much and we had so many great performances, some of which didn’t make the film. The record is 26 tracks and the film highlights 14. So there’s a lot of music and a lot of sessions. I really didn’t have an idea of where those sessions would go and how they might support the narrative.

I’m kind of old school. I have 3 x 5 cards, and we were trying different ways to put it together. I knew what the narrative was going to be, which helped put together the combinations and the collaborations—this idea of pre-Katrina, then Katrina, then post-Katrina. So it’s a three-act play, and the sessions are a three-act play, too. So I had a very broad construct and said, “OK, we’re attempting to tell the story of where and what and why.” I’ll tell filmmakers, “If your audience doesn’t know what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, how you’re doing it and why they should care within the first couple of minutes, then you probably have to go back and retool a little bit.”

So we had a broad construct and then we weaved the narrative together after seeing what we had. In our case, it was thousands of hours of film because I had eight cameras running the whole time.

Where the rubber meets the road is trying to create a cohesive narrative that’s going to play for the home team. Ultimately, if it plays for New Orleanians or Memphians, then I know it’ll play everywhere.

These films also are entwined with an educational mission. What is ongoing and what do you have in the works?

In terms of our educational outreach, that is really why we exist. Our records, films and tours are all about supporting that.

Berklee College of Music is our long-term education partner. They’ve been our partner for over 10 years and have commissioned the Common Core Curriculum that is in high schools and middle schools across the country for Memphis. We are now developing New Orleans. We have one of the five modules completed, and we debuted it to the New York City Public Schools for Professional Development Day this past January in front of 750 teachers at LaGuardia High School. We had 150 teachers up onstage playing “Lil Liza Jane.” So it was a lot of fun.

Berklee and Take Me to the River have partnered with Soundtrap, which is a Spotify company that has an online suite of recording tools and everything students need to record music and to collaborate with other like-minded students.

So that’s the way our curriculum is distributed to high schools and middle schools across the country. The New Orleans curriculum will be ready for the beginning of the next school year and it’s distributed through Pulse, which is Berklee’s proprietary online suite of tools for students, and through Soundtrap.

The college course that I was teaching at The New School for three years is being retooled at Berklee, and it is being developed into a capstone senior class. So it’s the last class you’ll take in getting your Africana studies major.

All the classes utilize assets from Take Me to the River. So we’re super excited about our education initiative and look forward to continuing to grow the education piece of what we do.

Right now, we’re also filming Take Me to the River: London. It’s telling the British Invasion story differently. We’re making a new record and navigating the film through sessions utilizing legendary legacy British Invasion artists together with those artists who influenced and inspired them from the Mississippi Delta and Louisiana, as well as younger stars who are being inspired and influenced by the same artists and, to some degree, the same songs. I think that’s bringing the Take Me to the River story full circle.