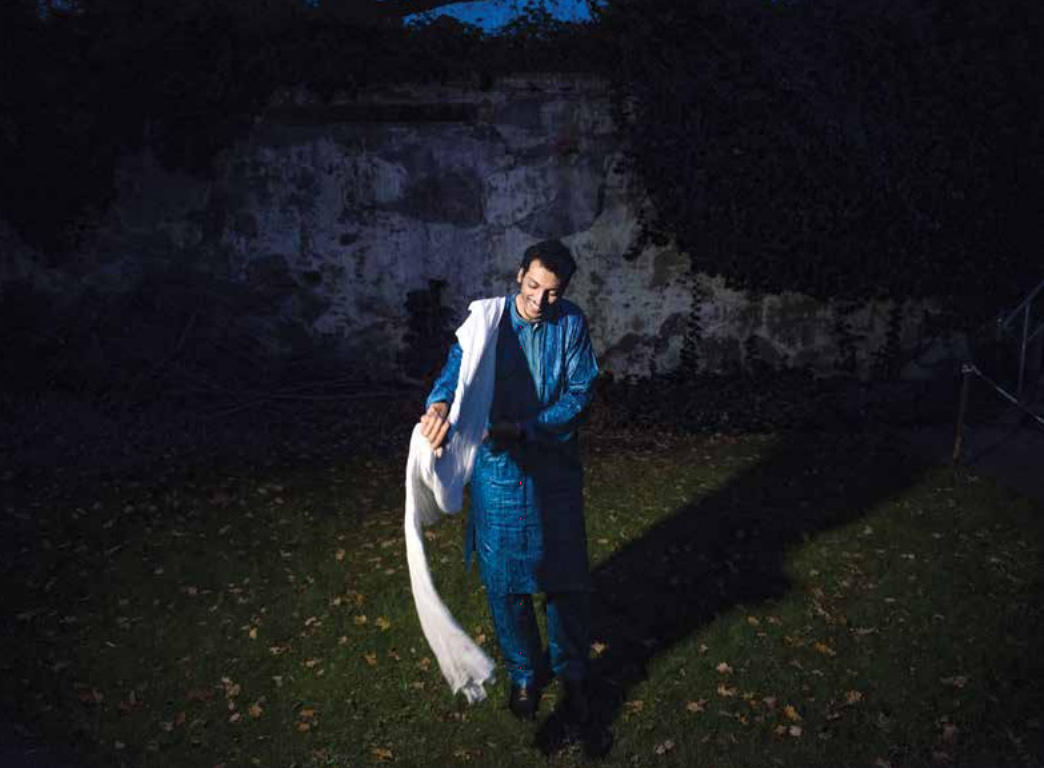

Spotlight: Bombino

Bombino might have been a truck driver if he hadn’t been blessed with a musical gift. The 36-year-old guitarist and singer from Niger creates music that can evoke the stark beauty of the vast desert, while conjuring images of guitar-god flamboyance. The extravagance is in the playing, not in the presentation. At its core, the music is humble enough, taking ornamental touches and elevating them to hypnotic levels. On his new album, Azel—his third studio recording, which was produced by Dirty Projectors’ David Longstreth— Bombino plays a mix of electric and acoustic, sometimes backed by a band, sometimes accompanied by hand drumming or clapping. (The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach produced Bombino’s last studio album, 2013’s Nomad.)

Born Goumar Almoctar, Bombino has a guitar style that is pyrotechnic without being showy. On “Inar,” his acoustic sounds out—stuttering grace notes that turn back on themselves, bursting forward in cascades like the sound of a kora. At other times, Bombino thrums out droning notes with his right hand, while the fingers of his left hand flutter and pull away at the strings in rapid figures that can sound almost like a bagpipe—the phrases hinge and pivot on these kinds of accents and filigrees. Other songs, like “Iyat Ninhay,” open with astounding double-tracked electric guitar statements and slide into ominous riffs that, set against more plodding beats, might be at home on a Black Sabbath tune. His singing is soulful, and the tricky offbeat accents give the music a reggae feel in some places.

It’s emblematic of the music of the Tuareg, the traditionally nomadic ethnic group that lives along the Sahara in parts of Mali, Niger and Algeria. (Bombino has called some of their hybrid grooves “tuareggae.”) Groups like Tinariwen and Etran Finatawa have helped connect this guitar-based music with listeners from beyond Africa. As with those groups—and related artists like Ali Farka Touré—Bombino’s music is often labeled “desert blues,” with its loping rhythms, modal grooves and call-andresponse structures. Bombino initially found a wider audience when Hisham Mayet, the co-founder of the Sublime Frequencies label, recorded him at a 2007 wedding in Agadez.

“Even today, I play a lot of weddings,” Bombino says in an email, which was translated by his manager. “Weddings are the main source of income for musicians in Niger, effectively.”

Niger hasn’t always been so welcoming to the Tuareg. Following a rebellion in 1990, Bombino, then a boy, and his family fled to Algeria and later to Libya. These were formative years for him as a musician, as he picked up riffs and techniques from watching Jimi Hendrix videos, an influence that remains clear in the ornate percussive flourishes of his left hand. Later, the government in Niger banned the guitar among the Tuareg, since it was viewed as an instrument and symbol of rebellion. By this point, Bombino was making a living playing guitar. When two of his bandmates were executed, he moved again, to Burkina Faso, on the other side of the Sahara.

He was featured, along with other Tuareg musicians, in the 2010 documentary Agadez, the Music and the Rebellion. For many years, hostilities against the Tuareg had been a source of violence in these regions at times, but in recent years, the political climate has changed and Islamic radicals have become a more pressing security concern.

“At this moment, things are basically peaceful in Niger, despite the grave problems in Mali, Burkina, Nigeria and others,” Bombino says. “Of course, there are still very big problems, and there are regions in Niger that I would say are not safe for foreigners, but, at the same time, Niger is doing better politically than I can ever remember, in terms of integration and solidarity among all the ethnic groups of Niger. We Tuareg returned in 2009 and, since then, the society has become much more open to the Tuareg people and accepting of our rights and our culture. For me, this is a major victory, even if we continue to have serious problems.”

Bombino has been able to return home, and he currently resides in Niamey with his wife and daughters.

“There is a magical feeling in the [Sahara desert] that you cannot experience anywhere else,” he says. “And what makes Agadez special is the people there who are so kind. Agadez is a poor town but the culture there is rich and beautiful.”