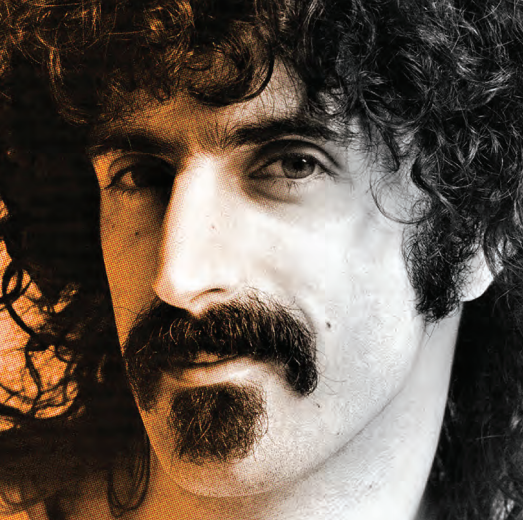

Securing Frank Zappa’s Vault

Laurel Canyon is an affluent hideaway neighborhood in Los Angeles, an idyllic enclave between the San Fernando Valley’s suburban sprawl and the notorious glam of Hollywood’s Sunset Strip. In the 1970s, the hillside haven hatched the singer-songwriter scene immortalized by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s “Our House” and became the backdrop of the grisly Wonderland murders in 1981. For composer and avant-garde musician Frank Zappa, his wife, Gail, and their four children— Moon, Dweezil, Ahmet and Diva—it was the perfect home.

Ahmet was just a child when the clawing, gnashing machines came and devoured the family’s front yard. On orders from Frank, a promising patch of green was replaced with an enormous hole earmarked for a subterranean chamber of concrete and concealment or, more precisely, the Vault.

Not long after purchasing the 1930s Tudor, Frank set out to transform part of the six-bathroom, seven-bedroom house into his personal laboratory. He constructed a rehearsal space and full recording studio, dubbed the Utility Muffin research Kitchen. And he built the Vault, with rows upon rows of shelving stretched wall-to-wall and floor-to-ceiling for the storage of boxes and boxes of audiotape and film, under the most ideal of atmospheric conditions.

In music’s modern parlance, the word “vault” has become a marketing dinner bell, ringing every time a record label needs source credibility for another lost track or vintage concert excavated from the rock-and-roll catacombs. It’s the go-to seductive axiom—“from the vault”—luring any fan base insatiable in its desire for more pieces of the past. For the Zappas, it was the word that filled the crater in their lawn.

“The Vault was a very exciting thing growing up in our house,” says Ahmet Zappa, who is now 42. “They dug out a massive, massive climate-controlled room organized to be a safe place, under lock and key, like a library.”

Frank taped everything— every session, performance, rehearsal, even casual jams at the house. If he didn’t like something, then he taped over it, and by the time of his death in 1993 of prostate cancer, he had amassed decades of recordings that have served as the basis for over 100 albums from their creator. He also left behind the precarious questions of his legacy: Who would manage the Vault, and what would be done with its contents?

For a short time, Mike Keneally, a former guitarist for Frank’s bands in the ‘80s, helped the Zappa Family Trust, directed by Gail, maintain the Vault. In 1995, the archive found its Vaultmeister in Joe Travers, a one-time drummer in Ahmet and Dweezil’s band, Z. After 22 years of identifying, cataloging, transferring and preserving the trove, Ahmet suspects Travers is only halfway through the immense collection.

“It’s a musical Hogwarts,” Ahmet says.

Frank considered the tapes important commodities—both the finished products and, more important, the raw materials. Often, he would extract sections, or select solos, from live performances and edit them into either studio takes or other concert recordings. A savant’s sense of recollection fed his perfectionism.

The great Roman Orator Cicero is said to have remembered his speeches by storing them in a mind palace, accessing the words by visualizing them as parts of an imaginary room. The Vault was Frank’s palace; his recall was like a human card catalog.

“I trip out on how he made these recordings,” Ahmet says. “He was someone who could remember the room tone of the places he played, plus the tempo of the song, to be able to match these recordings from different shows together. He kept that in his mind. It’s fascinating to me.”

So much has changed in the 23 years since Frank’s passing, most notably the ubiquity of digital information and its virtually infinite storage capabilities. The fragility of reel-to-reel tape only increases over time. “There is nothing more important than that original tape master,” Travers says. However, he knows that to both utilize and preserve the music, it must be converted to a digital domain.

Travers works to transfer every note from every inch of film to a digital format at the highest available conversion rate, and, ideally, for album masters, also create an analog safety copy. And, he concedes, the technology is constantly updating, with formats often migrating, leaving him resigned to the fact that “there really is no end in sight.”

Still, the real fun is in discovering and releasing the music. Ahmet and Travers view themselves as archaeologists, unearthing history one tape at a time, down to the fingerprint . “When we transfer the tape, we’re looking to see if Frank left any touch points,” explains Ahmet, “to see if he took anything from that tape.”

As with most archaeologists, they have their quests. Some are rooted in mythology and legend; others are grounded in fact. Somewhere in the endless stacks, Ahmet says— and Travers believes—is their Holy Grail. Somewhere in one of those cardboard boxes is a tape of Frank playing with Jimi Hendrix at the house.

“I talked to Frank and Gail about that day. I was like, ‘Frank and Jimi were just jamming, and they recorded that?’” says Ahmet. “We found [a tape of ] Eric Clapton and Frank just jamming. I would imagine that the Jimi Hendrix recording is the same way.”

Of the 100-plus releases credited to Frank Zappa, roughly 40 have come out since his passing, with the posthumous catalog under the executive control of Gail and the Zappa Family Trust. Following Gail’s death in October of 2015, leadership shifted, per her wishes, to Ahmet. Among the more conspicuous recent developments is a partnership forged between Zappa Records and Universal Music Enterprises.

“Universal’s really happy. We’re really happy,” Ahmet confirms.

“Frank Zappa is one of the most important and influential artists in music history,” says Bruce Resnikoff, president and CEO of Universal Music Enterprises. “With his legacy protected and guided by Ahmet Zappa and the Zappa Family Trust, we are privileged and look forward to collaborating and bringing his creative legacy in various forms to his new and longtime fans.”

In November of last year, Universal simultaneously released a trio of albums across three formats—digital, CD and vinyl—signifying an enthusiastic and aggressive approach to the new relationship: The Mothers of Invention’s Uncle Meat recast as Meat Light, a three-disc set including the original 1969 vinyl mix; Chicago ‘78, an unreleased concert recorded at the Uptown Theatre, presented in its entirety; and Little Dots, a sequel to Imaginary Diseases, featuring the 10-piece ensemble Petit Wazoo from the 1972 tour.

The Chicago ‘78 show, in particular, provides an insightful look into the trials and triumphs of the process. “That was one of Gail’s requests, a show from that year,” says Travers.

With that instruction, he went to work. Pulling tapes from 1978, the quality of the Chicago show stood out. There were problems, however.

Tape has finite length, and needed to be changed at various points during the concert. Gaps could, and often would, occur while the band was performing. To fill these spot , Travers sought out alternatives, like a separate second tape and a mixing-board cassette, editing the three into one uninterrupted sequence— a process he outlines rather specifically in the album’s liner notes.

This effort speaks to the meticulous attention to detail that the self-professed geeks Ahmet and Travers strive for in the preparation and presentation of each album. “We raise the bar in keeping as much information available to the consumer [as possible],” says Travers. “In the audiophile world, those types of details mean a lot to people.”

“I like the minutiae,” says Ahmet. “I like the historical nature.”

“That’s why it’s important that we listed where we got the other sources,” Travers concludes.

Quality control is paramount. Travers laments the days he cues up a reel only to discover an engineer’s poorly crafted house mix of an otherwise excellent performance. “From a historical perspective, it can be really disappointing,” he explains. “The older the tapes are, the greater the chance is to not have the kind of releasable fidelity you would expect.”

Among the most challenging projects was the completion of a concert film originally intended for release four decades prior. Plagued by technical complications, Roxy: The Movie was filmed and recorded over three December nights in 1973 at the famed Sunset Strip club of the same name. Simply put, an equipment failure that was not realized at the time resulted in video and audio that could not be synchronized. The tapes went into the Vault.

Frank did assemble a terrific album, Roxy & Elsewhere, from the scrapped plans, but the original concept of a concert film had to wait on technology. Through a painstaking procedure matching every frame with every note—possible with digital editing advancements 40 years later—Gail and Ahmet worked tirelessly with editor John Albarian to finally realize Frank’s vision.

“Some things we couldn’t put out 10 years ago, [but] now we have so many releases we can do,” says Ahmet.

A week before the film’s debut, Gail died of lung cancer. “We did it, Mom!” an emotional Ahmet shouted at the movie’s Hollywood premiere.

As a trustee, Gail was heavily involved in every aspect of the family business, right up until the end. This past December, Frank’s 200 Motels (The Suites), which was produced by Gail and Frank Filipetti, was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Classical Compendium. “200 Motels (The Suites) was an important project for Gail and a real labor of love. It was one of the last albums my mother worked on creatively,” Ahmet said in a press release.

Transitions can be difficult Gail’s chosen successor has experienced some clashes with his siblings. The most public ones were Ahmet’s exchanges with his brother Dweezil over usage of Frank’s name in merchandise, which played out, to Ahmet’s expressed dismay, in open letters on social media and in The New York Times. As Freak Out!, The Mothers of Invention’s debut, marked its 50th anniversary this past summer, the Zappas’ Laurel Canyon estate was sold, reportedly for $5.25 million to pop megastar Lady Gaga. On social media, fans of Frank’s expressed their hopes that she will keep the quirky compound relatively intact.

“With my mother’s unfortunate passing, there was so much going on—all the things that needed to happen over that year,” says Ahmet.

Optimistically, he looks to the opportunities ahead. In May, Ahmet plans to open Utility Muffin research Kitchen’s new location, and a home for a new vault. “When you’re in the control room, behind you will be windows into the room, and you’ll be able to see just how much content Frank made,” Ahmet says. “It will be the crown jewel of this space.”

Above the internal squabbles and business dealings, Ahmet says that his priority remains pleasing the fans. It was a Kickstarter campaign to fund Alex Winter’s documentary Who the F*@% Is Frank Zappa? that opened new avenues into that community. “The communication between the fans, how passionate they are about Frank, was different through the Kickstarter environment than the way we were communicating with people through Zappa.com,” says Ahmet. “It gave us this dialogue back and forth that I was overwhelmed with.”

He talks of an impending website overhaul, where content will be easily searchable, including more video. In the middle of his excitement, he brainstorms an idea with Travers. “This is me spitballing right now, but we might consider a fan request— people that were at a show and wanting a specific song the remember from that night. Pick all those moments and put a disc together,” imagines Ahmet. “That might be really fun.”

Frank Zappa’s Vault, this voluminous accumulation of his life’s work, continues to mirror its maker in the best possible way. It’s vast and somewhat mysterious, perhaps even intimidating, yet still accessible—and bound to keep his family and fans entertained and curious for a long time.

“People are discovering Frank now more than ever. We could just put things up and not care as much. But, for those real audiophiles, we maximize our budgets to make these sets as good as we possibly can,” says Ahmet. “I couldn’t be happier for Frank.”