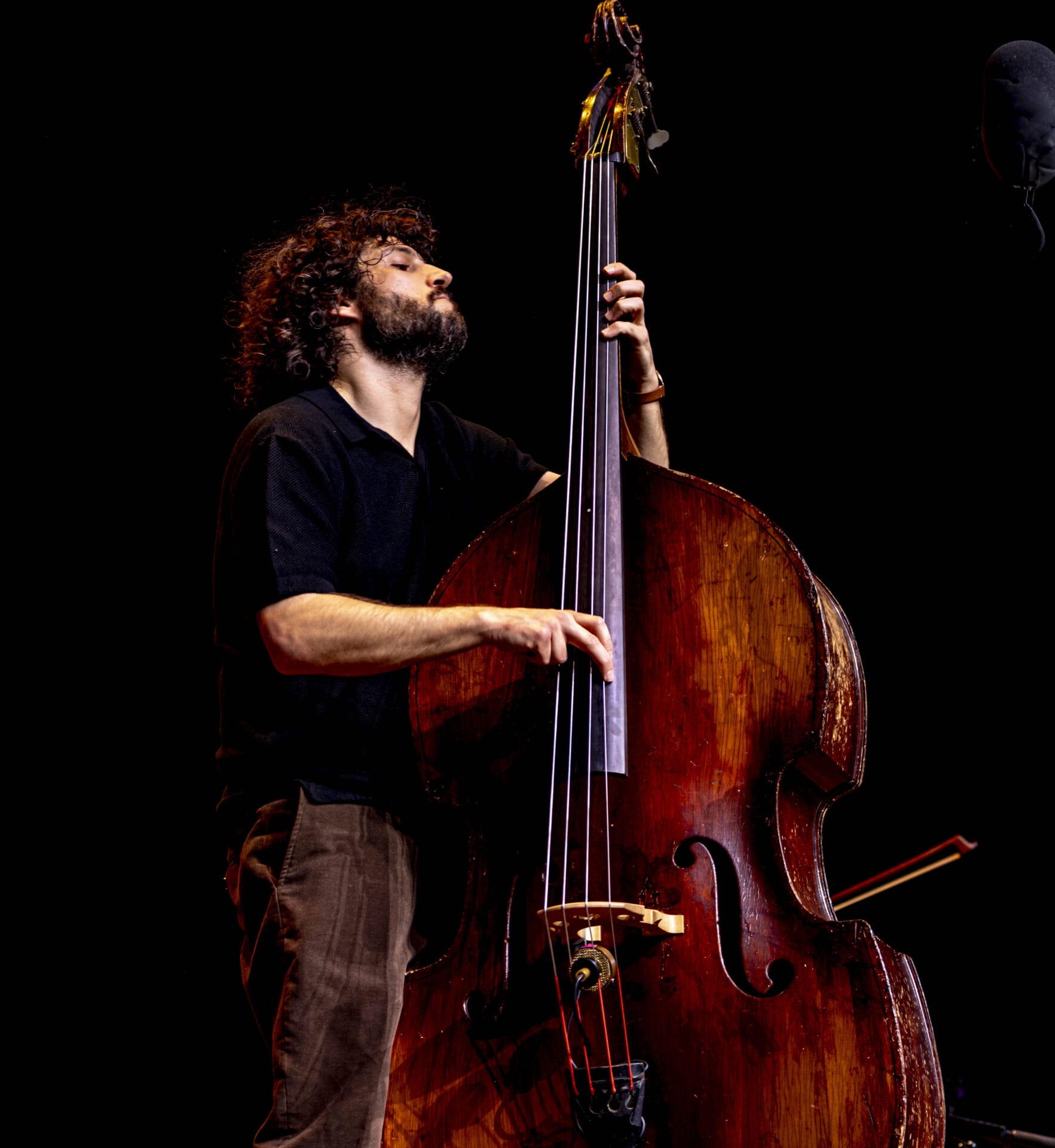

Sam Grisman: True Blue

Photo: Jean Frank

***

Most Grateful Dead fans never had the chance to see Jerry Garcia perform in their childhood living room. But then again, most Grateful Dead fans aren’t Sam Grisman.

If the last name doesn’t give it away, then a quick listen will: Sam’s the son of virtuoso mandolinist, composer and bluegrass innovator David “Dawg” Grisman.

There’s a likeness in their voices and a precision in their expressive instrumental articulation, but the most striking similarity is the music they play.

At 35, Grisman carries his father’s legacy by offering thoughtfully passionate renditions of his dad’s acoustic instrumentals. He accentuates bluegrass standards from Bill Monroe and John Hartford, positioned beside stripped-down takes on the Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan.

He does this with Sam Grisman Project, a confluence of bluegrass torchbearers and road dogs who, depending on the night, could be headlining a gig or touring in support of artists such as Bruce Hornsby, Kacey Musgraves and Molly Tuttle.

Grisman embraces a looser approach to the jam scene’s “and friends” concept. The core players—himself and percussive constant Chris “Hollywood” English—turn in over 100 gigs a year at marquee theaters and choice festivals. The pair is joined by a rotating lineup of coast-to-coast representatives who add guitar, clawhammer banjo, fiddle, mandolin and their own originals.

It’s not a foolproof concept to gain a following while performing acoustic music through condenser microphones. Yet, Grisman continues to sell out hushed rooms to multi-generational listeners, who stick around even after the show to say thanks and share a moment with the palm-pressed picker.

***

In two short years, Grisman went from his debut run to the Ryman Auditorium, sharing a bill with Peter Rowan and welcoming Sam Bush, Tim O’Brien, Jerry Douglas, Lindsay Lou, Ronnie and Rob McCoury, as well as unannounced guests Gillian Welch, David Rawlings and Billy Strings. He also completed a Northeastern duo tour in late January with Leftover Salmon’s Vince Herman, performing upright bass and guitar arrangements in the spirit of John Kahn and Garcia.

In March, Grisman will celebrate his father’s 80th birthday by conducting a retrospective of early Dawg tunes with support from Dominick Leslie, Ronnie McCoury, Alex Hargreaves and Strings.

“Being able to curate an evening of music or a show that honors somebody’s catalog, or a particular set of instrumentalists in the best possible way, is something that I strive to do,” Grisman imparts. “It’s not that we’re recreating the original recording necessarily, but it’s nice to be reverent to it.”

Grisman’s admiration for acoustic music is rooted both in his father’s playing and his constant exposure to Dawg’s roster of ‘90s contemporaries. During his first year as a bassist, and at his dad’s lead, he solely focused on the one-chord “Sally Goodin,’” a master class in groove and timing that informed years of practice.

“ I grew up learning from experience and getting a handful of really great private lessons from guys like Todd Phillips, Jim Kerwin and Edgar Meyer, who, you know, kicked my ass a couple of times,” Grisman says lightheartedly.

Like any kid with a musical curiosity prior to the turn of the millennium, Grisman sifted through his dad’s CD collection in search of something electric, feeling the growing pains of his acoustic regimen.

“There would be a lot of electric music and old records he played on in the ‘70s—American Beauty was in there. [Dawg contributed mandolin on ‘Friend of the Devil’ and ‘Ripple.’] But, the little Stealie and the cursive on the white spine of the record drew me in as a little person,” Grisman says. “That’s ultimately how I gravitated toward the Grateful Dead—because my dad had a copy of One From the Vault in the little section of his CD collection, in the stuff that he had either played on or had been given.”

He grins in recognition of the defining moment, then admits, “It wasn’t until I discovered that CD that I put it together that Uncle Jerry—who came over and just played folk-music tunes in the living room when I was a toddler—was a huge rock icon.”

Grisman continued his musical education under Dawg’s watch. Attending a handful of camps, he even crashed RockyGrass Academy, seeking opportunities to jam with fellow bassists Mark Schatz, Mike Bub and instructional precursor Phillips.

By his teen years, Grisman had proved to be a reliable sideman and earned a slot on tour with his dad, learning the ways of his elders and gaining the skills that would make him the latter-day figurehead of Dawg music. Yet, the joys of his adolescent discovery fueled another side of his interests that never seemed to dim.

“The significance of the music of Jerry and the Grateful Dead is so far-reaching and has its influence in the most unexpected places sometimes,” says Grisman. “That’s how we get shown the light.”

***

Just as Sam Grisman Project was gearing up for their first tour, Grisman received an opportunity to join Bobby Weir during Sweetwater Music Hall’s 50th anniversary concert, solidifying his status as a carrier of the songbook.

The pivotal moment reflected the payoff, and Grisman’s years of hard work and practice have since translated into captivating, sentimental acoustic performances night after night.

Grisman leads a lineup of more than a dozen musicians, who split their time between personal projects and supporting bluegrass giants, country songstresses and jam icons. “ I don’t want to keep anybody from doing what they truly love to do, which, hopefully, includes what we’re doing,” Grisman says, acknowledging his band’s varying commitments.

On the group’s regionally specific runs, Grisman invites somewhere between four or six available artists from a pool of friends that includes Logan Ledger, Max Flansberg, Matt Flinner, John Mailander, Victor Furtado, Nat Smith, Dominick Leslie, Sam Leslie and Phoebe Hunt.

Like Grisman, the other members of the Project approach the material with profound integrity. They never set out to reinvent the classics, but they have enriched the concept of paying homage.

“I don’t sing any songs I don’t connect with,” Grisman states. “ I have to have a personal connection with the singer, or the subject matter , or a particular performance to make me fall in love with the song. I’m not in this to do a better version of whatever turned me on to this song ‘cause that’s not possible.”

The band shares in the sentiment, and their feelings are elicited through heartfelt on-stage moments. The effect is a reciprocal experience for fans and musicians, who share in the gratitude of the songs performed in the moment.

Their magnitude of respect has led to a series of co-bills with Rowan. “We’ve been playing half as a normal SGP show, a set of some of everybody in the collective’s original music and some material that we all love so much—in the spirit of good music and friendship.”

The other half is centered around Old & in the Way, the short-lived bluegrass project and subsequent album that featured Rowan, Dawg, Garcia, Kahn and fiddler Vassar Clement. The group’s namesake record delivered adaptations of The Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses,” traditionals “Pig in a Pen” and “Knockin’ on Your Door,” Rowan’s “Midnight Moonlight,” “Panama Red” and “Land of the Navajo,” and Dawg’s only song to feature lyrics, “Old and in the Way;” these selections have all become setlists favorites for Rowan and Sam Grisman Project’s current outfit.

“ I already had a sketch of what I wanted to play with Peter because so much of his music is so beloved by me and my friends,” Grisman raves. “He made all these tremendous records in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s with Andy Statman and Tony Trischka. Doing tunes like ‘Moonshiner’ and ‘Thirsty in the Rain’ has been a blast. You can tell Peter is tickled. He brings the music’s essence and spirit to the stage when we’re playing that stuff. It transports us and him to that place.”

“ He’s kind of alluded to wanting to learn a couple of Garcia-Hunter tunes,” Grisman notes of the mutual musical experience. “We’ll play a whole set and get off stage, and he’ll be like, ‘Man, what’s that?’ He was really digging ‘Althea,’ and I had this vision of Peter Rowan singing the shit out of ‘Althea.’ It’s not out of the realm of possibility.”

***

In January, the ensemble took their potent dose of nostalgia to the Mother Church. The occasion represented a return for Rowan and a first for Grisman. “One of the most magical moments of the evening was the start of the second set when Gillian Welch and David Rawlings came and just played with Peter,” Grisman says. “Peter actually walked out first and sort of ad libbed a whole song about the experience of being at the Ryman again.

“All of these heroes of mine were super game and supportive and let me write a setlist and say who was playing on what,” Grisman continues, referencing an evening that started with Sam Grisman Project offering “Jack-A-Roe,” followed by Garcia’s “Loser,” the Dead-associated “Waiting for a Miracle,” English’s own “Alone (‘Alright’),” Dawg’s “Hartford’s Real” and others.

The guest musicians reflected the cascade of covers and originals by shuffling on and off stage at Grisman’s purposive cue. “It was just a challenge to weave all these friends in and out, people who I really want to hear play on everything,” the bassist says.

Despite the test of integrating nearly 20 artists into a three-hour performance, Grisman excelled in the role of musical director. He also made good use of the days leading up to the Ryman in the studio, capturing the energy on tape. “We’re working toward a full-length SGP record that should be out very soon.”

He describes its contents: “It will be like an SGP show normally is—a good mixture of all different kinds of loved material. [They’ll be] something from Hollywood and Max, some really great songs that we’ve been playing in this band for a long time.”

Grisman wrapped his Nashville activities by celebrating his birthday in a living room full of pickers and players. He followed up weeks later with a four stop duo run with Herman. “It was really cool to see where our mutual interests lie musically and write setlists that reflect his influences and mine. To play some of his original music in a stripped-down instrumentation, with just guitar and bass as sort of a nod to Jerry and John Kahn, was really fun and something we definitely both want to do again.”

With everything 2025 has already garnered, Grisman considers the prospect of what’s still to come, speaking a month out from Dawg 80. “Putting that show on is gonna be another one of the great honors of my life,” he says. “Creatively, [my dad] talked about wanting to play some newer Dawg music with a whole rotating cast of characters from his past. He told me that he would like to see me put together a band of younger dudes to play older Dawg music.”

He notes, “We’ll do a retrospective of early Dawg music.” The frame will feature Hargreaves, Leslie, Ronnie McCoury and Strings, who was not included in the initial announcement. It seems, to me, like he wants to see Dawg music in safe hands with the younger generation.”

Grisman’s status as the bloodline representative of Dawg music goes beyond the shared last name. It is the continuation of the acoustic spirit and bluegrass traditions he was raised on and lives by—a no-iPad approach, banking on the knowledge of firsthand experience and deep admiration.

“It’s really important that the overarching mission of this band is honoring our heroes,” he affirms. “[It’s about] getting to play music with the people whose songs shaped our path and giving them their flowers while we can.”