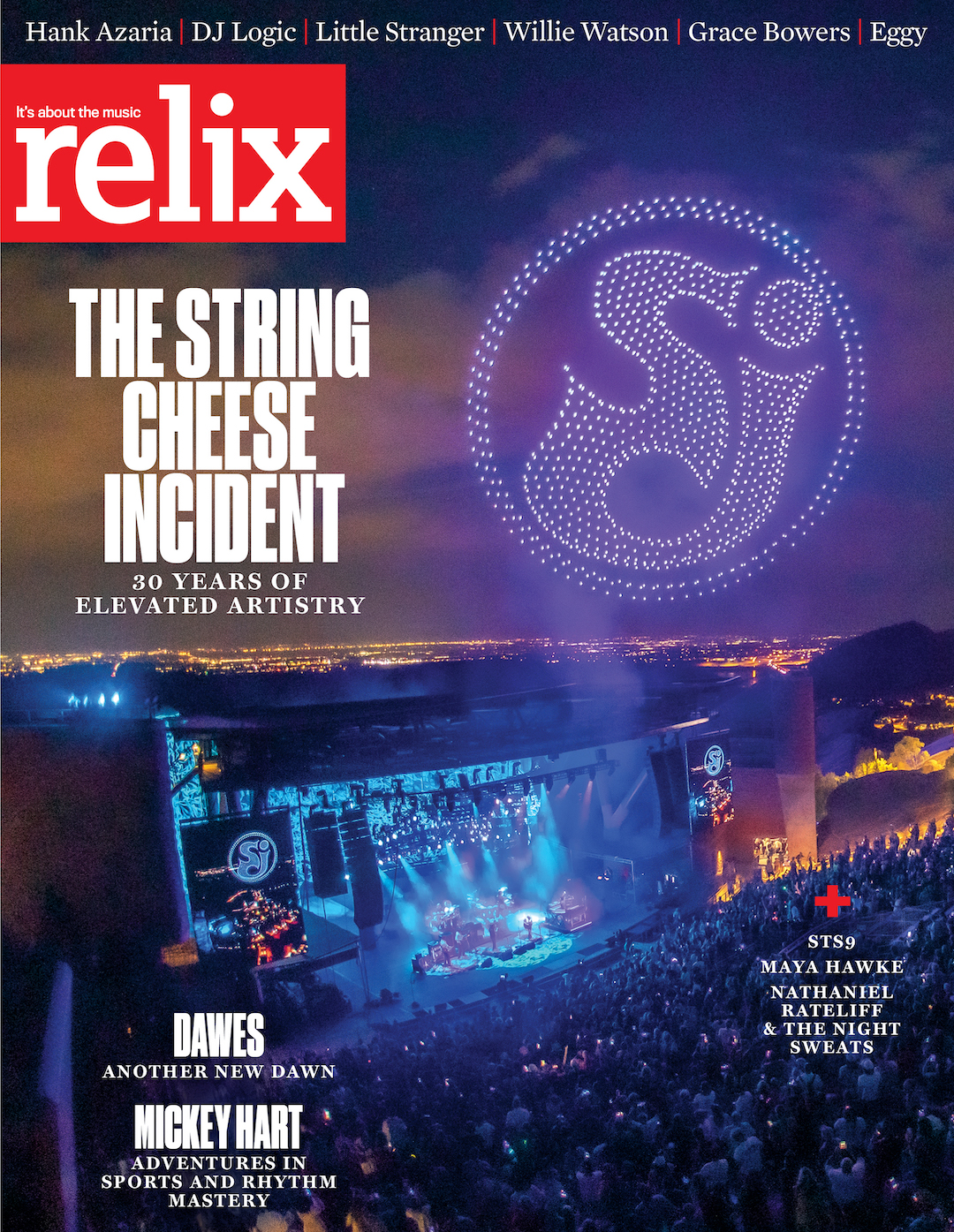

Ryan Adams: I Really, Truly Still Love You, New York (Excerpt)

This excerpt originally appears in the March issue of Relix. Click here to subscribe.

This excerpt originally appears in the March issue of Relix. Click here to subscribe.

Black & White is located in New York’s East Village, just south of Union Square’s mall-like glaze and a few avenues west of the long-gentrified squalor that gave birth to the city’s original DIY movement. In many ways, it’s one of Manhattan’s last old-school, TV-less rock-and-roll bars; the type of watering hole that hosts poet-friendly open-mic nights and where an indie darling can spin old soul records anonymously while the occasional art collective meets next to a portly barfly with equal cred. It’s also a place where authenticity trumps popularity, from punk to funk, and where Ryan Adams can still get gently scolded by a bartender, with a distinct Ronnie Wood quality, for breaking his “no Neil Young” rule by practicing “Cinnamon Girl” on his acoustic guitar.

The bar is an older-brother venue in a family of nightlife establishments run by Johnny T. Yerington—one of Adams’ closest friends and his occasional drummer—and, when he’s in New York, the Los Angeles-based Adams likes to hang around its basement. There’s something about playing with Yerington that allows Adams to access his rawest songwriting emotions, and though Prisoner— his first LP since his high-profile divorce from actress/singer Mandy Moore— was partially inspired by the ‘80s bangers he listens to when he runs, it also feels very punk rock.

“I could feel that it was going to happen when I saw Johnny,” Adams says of the November 2014 trip that laid the seeds for his 16th album. “I was in New York playing Carnegie Hall and, just being back here, I got really inspired.”

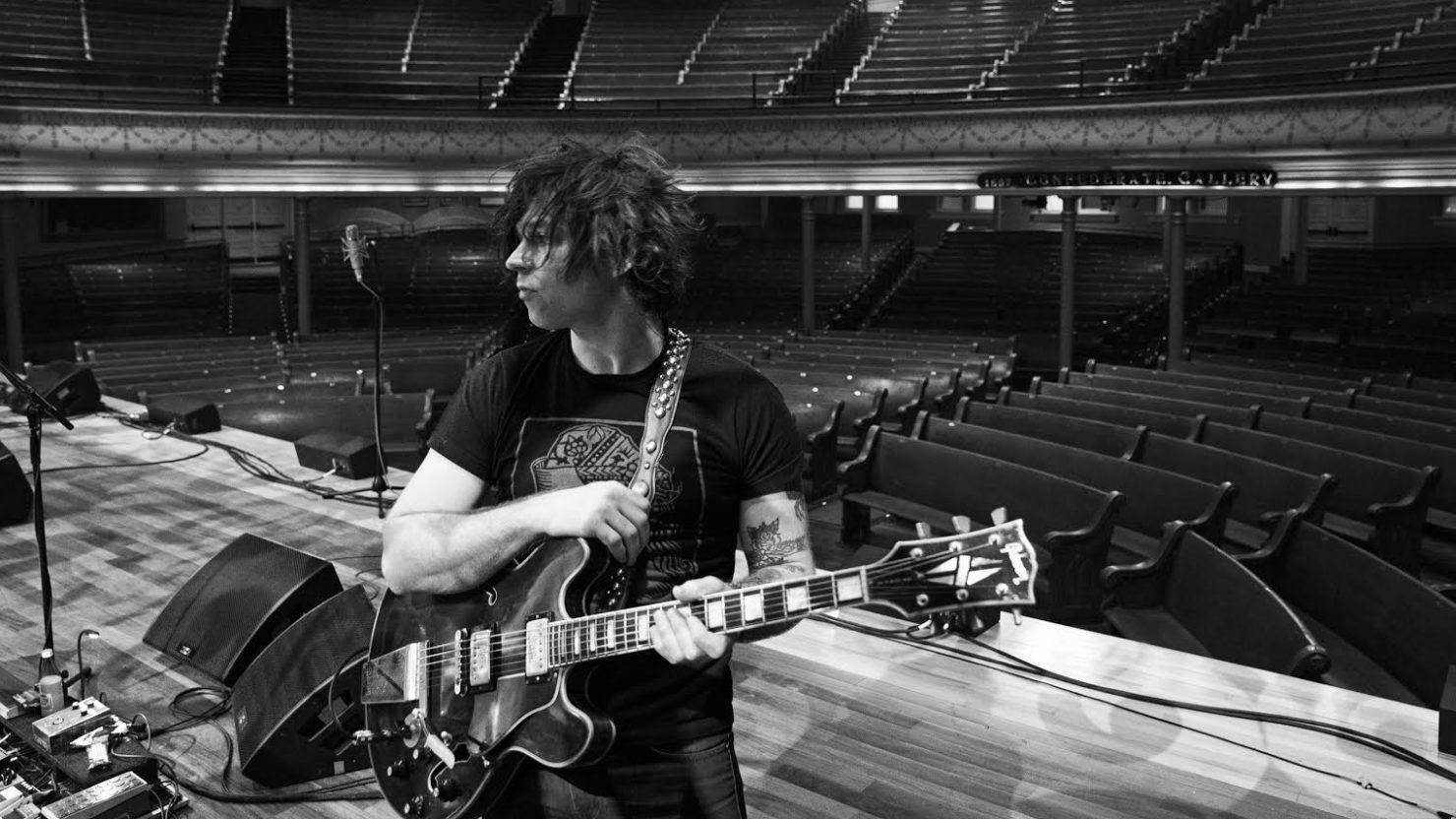

It’s a cold afternoon at the tail end of 2016, and Adams is currently camped out a few blocks from Black & White at Electric Lady Studios, between international dates with his new backing band and a quick trip to Pennsylvania for the holidays. Jimi Hendrix, who lived four blocks north when he died, originally envisioned Electric Lady as something of his urban garage, yet it’s Adams who has truly turned the now-iconic Greenwich Village studio into his sonic lab during his wild ride from North Carolina-bred folk wunderkind to New York indie icon and LA studio cat, and then back again.

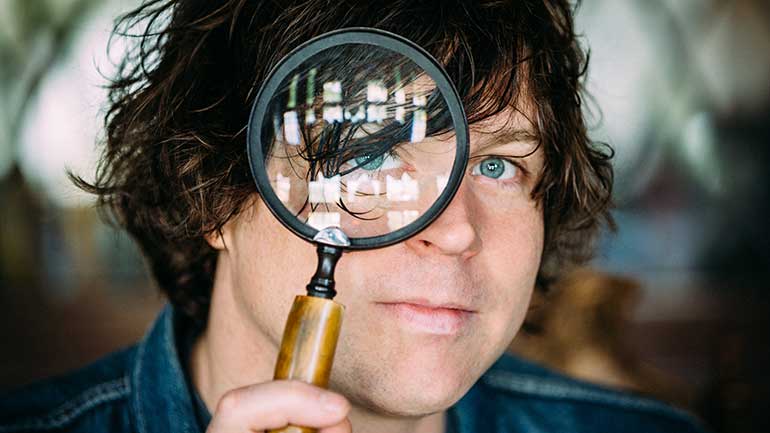

“I was inspired to get back here for a couple different reasons but, mainly, in that little bit of time I had in the city, I really felt alive,” Adams admits as he lounges in Electric Lady’s Studio A, wearing a Motörhead sweatshirt over a fitted Batman tee. “I was pretty down and not feeling it in my personal life, and then, all of a sudden, being around old friends, I started to light up. The energy of this place was really conducive to remembering who I was. I had been in LA for a long time before that, and it was fine— but it was a different life. There was a stress on me—not just from touring but from life— that I couldn’t have alleviated if I hadn’t had the experience of coming here when I did. Plus, there are a few legit modern pinball places nearby and I liked a girl here, so I was like, ‘Fuck it.’”

Prisoner, which was released in mid-February, is the emotional exclamation point at the end of Adams’ marriage to Moore and signals the start of his next phase as a songwriter and bandleader. In early 2009, around the time of his wedding, Adams broke up The Cardinals—the cosmic-cowboy group that made him an unexpected Deadhead favorite—and temporarily retired from the road while he battled Ménière’s disease (an inner-ear disorder that causes vertigo and can lead to tinnitus). He moved to Los Angeles and hunkered down at home—releasing the metal album Orion and two collections of poetry—but, for the first time since he helped popularize alt-country in the late ‘90s with Whiskeytown, Adams flew under the adar.

After an 18-month break that felt much longer at the time, he started dipping his toes back into the live arena in late 2010 and returned to the road the next year for a solo acoustic run supporting his then-new record, Ashes & Fire. By 2014, Adams finally felt healthy enough to put together The Shining—a full, electric band—and wrote and released a self-titled album with the help of his new guitarist, Mike Viola. But he continued to struggle with Ménière’s on the road.

“It happens after planes and stuff,” Adams says of his condition. “At some point on the last tour, I suffered a pretty horrific episode. Most of my energy is being spent just staying upright onstage for those two hours. I can exercise and do things to keep myself going at that pace and stay fine— stay level—but there are times when my adrenals just crap out. The stress of the tour… I was really enjoying the tour, but we were hitting it pretty hard. There was stuff in my life at the time—being in the stages leading up to a divorce—and, for more information on that stress level, watch any TBS movie. But all the clichés about divorce are real, whether you play guitar or not. So that stuff was all adding up, and I had a really bad Ménière’s episode. I’ve done a lot of hypnotherapy for it because I don’t want to regulate the pain. I just want to deal with it in a [Henry] Rollins way. But I couldn’t deal, so I needed a break.”

On Jan. 23, 2015, Adams and Moore announced the end of their marriage in a joint statement, and the couple legally parted ways the following year. While Adams has weathered his share of celebrity romances, the divorce and an alimony claim related to their pets dragged him deep into the gossip columns. He continued to write and record through the pain, releasing a complete, surprisingly sincere re-creation of Taylor Swift’s 1989 in late 2015, and working at both Electric Lady and his PAX-AM studio in LA whenever possible.

“It was the first break I’d had in a long time, where I’d seen a doctor and they said, ‘You’re fucking exhausted; you’re tense,’” Adams says of the period after his episode. “I wasn’t sleeping, I had severe compression in my ears and I just couldn’t alleviate it. I was still playing fine, so they gave me some medicine to try and relax and calm me, and told me to rest. It was the first minute I’d had to just chill the fuck out. I also got into PlayStation right around that time, and it’s the first time I actually got into edibles.”

Adams says that the video game Mad Max helped him manage his Ménière’s, but he still clearly had a lot on his mind; he’d been struggling to write on the road for a few album cycles. Eventually, he started seeing a hypnotherapist named Kerry Gaynor to help him stop smoking and figure out why he “felt so lost, trapped and disconnected” while making Ashes & Fire.

“I lost a lot of mojo at the end of The Cardinals, and then it remained lost for a long time out in LA until I worked with Kerry,” Adams says. “He figured out, through our conversations, that I had become disenchanted with the way music was going. I was so offended that people weren’t interested in records anymore that, on some really crazy, unconscious level, I felt like this thing that I risked my whole life to be involved in was somehow gonna go away.”

Though Adams is a fan of certain elements of the current wave of “adventurous pop music,” he still has a sense of humor about it. He sarcastically recounts hearing Rihanna’s robotic vocals— “screaming, ‘Having sex with me is amazing’”—blaring out of a jewelry store at an airport while he walked by. Suddenly, he says, he was nostalgic for the days when he’d complain about elevator music.

“So I couldn’t write anymore,” he continues. “I loved to play guitar, but it hurt my feelings to do it. So that bitter seed was growing this horrible thing in me. [Kerry] said to me: ‘You’re gonna pick up the guitar and you’re gonna remember what it was like when you were 15-16 years old, when it didn’t mean anything to you.’ It’s so hard to get back to that but I did and, ever since that happened, I’ve never felt so fucking good about something in my life. I just felt so optimistic.”

Finally, after struggling to scribble down ideas in his notebook for months, the floodgates opened. The spars , tender, saxophone-assisted “Tightrope” and the emotional shuffle “Outbound Train” poured out on the road; “Prisoner” was sparked on a bus ride while Viola was playing with a guitar riff in the front lounge.

“Then I was like, ‘Holy shit, I gotta go to the studio,’” Adams says. “So I did what any other person would never do. We had, like, two weeks off, and I called Johnny T. and I called this place [Electric Lady], and got on a plane and we started recording.”

Much of Prisoner was recorded live and, between takes, Adams and Yerington would run through hardcore and punk songs to take a breather from the “heartbreak material” they were producing. “We play for fun, but Ryan is always working toward a goal— it always means something,” Yerington says. “Ryan had a lot to say and a lot on his mind. I felt, from the first song, ‘Dive,’ that we were starting something that would be the next Ryan record.”

Adams popped into Electric Lady between tour dates throughout the next two years and threw his emotions into his songwriting. In total, he came up with a “business number” of 80-85 songs, 12 of which made it onto Prisoner, and a slew of ideas that are still boiling. “I wanted to come back here [to New York] and make music,” Adams says earnestly, noting how strange it feels to be at Electric Lady for a day of press instead of recording. “I met somebody that was cool as hell and I just wanted to hang out. The conveniences of what I had in LA didn’t match against ‘I’m going to jam with my best friend every day and go hang out and live my life—refuel and live.’ The parallels to Easy Tiger [released in 2007 as Adams was sobering up and stabilizing his life] are crazy because I used to live one block from [Electric Lady], and I just came here every day and basically stayed in the studio for a year. But in this situation, I was still on tour and started living here [in New York] out of a bag and one drawer. That’s what happens when I get into that environment.”

In the late ‘90s, Adams and Yerington met through fellow East Village musician and nightlife tastemaker Jesse Malin. Adams frequented their bar Niagara during the blurry period documented in his hit “New York, New York” and, after learning that Yerington had a rehearsal space nearby, they started jamming and making 4-track recordings. Though he says he has friends who still don’t believe him that he’s actually on Prisoner, Yerington has been involved in every one of Adams’ New York records in some way, including the manic Rock n Roll, an early version of Ashes & Fire and several side projects of varying levels of seriousness. He says they have “mountains of recorded stuff no one has ever heard,” like an unreleased album called Blackhole. “We always have a good time together and there is just a common trust between us. We have a certain telepathy when we play,” says Yerington. “We aren’t afraid to get stupid.”

Adams admits that writing and recording his past two records were such long, involved processes that he actually took a break from listening to music, except for when he was running. His self-curated playlists offer a mix of material—from Black Flag’s My War, Alice in Chains’ Dirt and Robert Plant’s “Big Log” to less expected ‘80s influence , like Bruce Hornsby’s polished work with The Range and Don Henley’s ubiquitous hit “The Boys of Summer.”

“The stuff I listen to when I run is the truth; that’s the shit that I love,” Adams says. Those sounds started to creep into his approach as well. As Adams worked through issues in his personal life, his sound started to morph.

“I started with this big, raw, rumbling, nasty, love machine, desire snowball rolling down fucking Divorce Mountain,” Adams says. “That’s who I was. That’s not a put-on. I’m a musician, a guitar player, a songwriter. I’ve never read a Bukowski book where he didn’t have something to say. There’s not a Henry Miller book called ‘Just Fuckin’ Around With the Typewriter.’ I have legitimate stuff to say because of what I have been through in my life. People have died around me. There’s a way of processing the world that can be beautiful and romantic, and I got to these songs and this process by starting in this way by necessity. If I were in a video game of my own life, then I leveled up so fast after those first songs.”

Despite any connotations associated with the word “prisoner,” Adams is adamant that the album’s title track—a lover’s lament protectively encased in a relatively chirpy pop song—captures his newfound feeling of freedom. “That’s just a love song that talks about how ridiculous it is to capture yourself in bullshit expectations—and unnecessary expectations about who you really are and what you really feel—but have an extraordinary amount of desire left in you for life and for things that are on the periphery. You’re basically only prisoner to yourself,” he says. “There’s a lot of concepts in Buddhism, Taoism, that we’re all mentally captive to the things that we think we want—those deeper, intrinsic pleasures. It could be love or sex or art or adventure.

“But for the most part, a lot of people will hold themselves captive, whether it’s to a job or their attitude. It’s that thing where people go, ‘I smoked pot and I had the worst panic attack and I’ll never smoke again!’ Once in a while, if you live long enough, you hear someone say that and you think, ‘Did you try sativa?’ or ‘Did you get a good look at yourself?’ Because imagine Mike Pence getting real fucking high and thinking about the shit that he says. He would go, ‘Oh, my God. I’m a living monster.’ And then he’d have to change. It’s like a mirror. That’s what that whole record, the entire body of tunes, is actually about.”

Prisoner is not a total departure from Adams’ previous work, but it does contain some unexpected flourishes. Lead track “Do You Still Love Me?” opens with an organ invocation, “Shiver and Shake” includes a wash of synths, and “Tightrope” fades into an outro that would fit snugly on a Range record. “Haunted House,” a number that Adams tried out during a few shows with jamgrass veterans The Infamous Stringdusters and Nicki Bluhm last summer, might be the album’s darkest selection— a spooky personal meditation that is more therapy session than Halloween spook.

A hallmark of 1980s recordings is the contrast between big, processed, synthetic production and dark Cold War-esque lyrical themes. Adams thought a lot about that approach while he was working through his own difficult period, and he absorbed some of the Reagan-era studio techniques Peter Wolf explored with Big Country and Jefferson Starship. He’s even discovered a newfound beauty in revisiting urgent songwriters like Bruce Springsteen and Tears for Fears in the confines of 1980s radio. (The 1990s is now where he feels production “gets weird.”) He’s also been listening to some of the Grateful Dead’s own more manicured late- ‘70s studio work, like Terrapin Station, and applauds their studio craftsmanship, apart from the “the MIDI stuff,” he says, “which makes me want to puke.”

“Skull & Roses, for me, is like reading The Hobbit; you don’t need to go any further than the black-typeface words on the white page to get yourself to that mountain,” he explains in Deadhead terms. “But sonically, by the time you get to Terrapin Station, I envision this physical space when I close my eyes.”

He scans the “live room” where he’s spent so many nights working on ideas and admits that he’s started to think of his diverse influences as his own “radio station, my own reference area.” The 1989 cover project wasn’t a direct link to Prisoner, however, Adams sees Swift as an ultimate example of a personal songwriter able to mesh over-the-top production and radio-ready pop hooks with incredibly unique arrangements. He decided to cover her album on a whim during one of countless PAX-AM recording sessions and the tribute was something of a low-pressure crossover for him; he’s still pumped that Swift was excited about it.

In addition to her own move from country to Top 40 at the height of her career, he thinks it was “super cool and ballsy” that the biggest pop star in the world released an album with a Polaroid of herself wearing a sweatshirt as the cover, with just a pair of initials listed instead of her name.

“Taylor Swift is really famous, but she’s also just a bro: She’ll write the hell out of a song,” he says. “Talk about somebody that can really get under someone’s nails in a song. We’re all just human beings and we’re all going through different levels of whatever relationships we have with each other. And they’re always gonna be complex, and there’s always gonna be tons of duplicity and mystery. That’s why songs that are political to songs that are personal are all interrelated and fun, and even sometimes funny to listen to.”

Along with Prisoner, Adams has marked this new stage of his career by putting together another group, featuring Grace Potter & The Nocturnals guitarist Benny Yurco, drummer Nate Lotz, bassist Charlie Stavish and keyboardist Ben Alleman, who Adams calls “Lieutenant Mahoney,” as if he were a “really spaced-out Vietnam veteran.” (Stavish, who worked with Adams as an engineer at Electric Lady a decade ago, is the only holdover from The Shining.) Adams had envisioned The Shining as “The Smiths meets Eddie & The Cruisers,” and says that “there was never any negative stuff in The Shining inter-band, but there were definitely bi-personalities that eclipsed each other.” He didn’t intend to form a new band, but he admits that “the truth about what it’s like to work with adults” is that you eventually lose your collaborators to steadier opportunities. And, last year, several members of The Shining, who have families and are hovering around middle age, decided to veer off the road.

“Though I was going through a divorce and was frantic, or some days just had upsetting things to deal with, I was trying to run that band and navigate that show,” Adams says. “There are aspects to divorce that go far beyond the emotional—that are fucking horrible, that cause major problems. And some of that stuff is just really upsetting, and you have to work through it, so I was really inundated with that. [The members of The Shining] were in their own worlds. We were bros, we were all fine—nobody ever really had a problem—but at the end of the day, those guys were getting up there and weren’t in a place where they really cared about crossing the globe to play. And I fucking live to play.”

Adams considers this latest ensemble a true, new band with their own arrangements of his extensive catalog—not “The Shining Part 2.” The Shining “basically got together by happenstance,” he says, through their work with Moore. The first time the trio of Adams, Viola and keyboardist Daniel Clarke wrote a song together, “White on Rice,” was by accident during an early backstage hang.

“[Mandy] called it. She was like, ‘You guys are gonna be in a band together one day,’” Adams says. “They also were really pretty bold, stepping into that role of me having a band again, and dealt with audiences expecting a certain sound and being compared to The Cardinals.”

Oddly enough, Adams spent his barnstorming years trying to shed his Whiskeytown tag in hopes of building a new project with its own identity, only to end up creating a band with a fanbase that’s just as hard to appease. “One out of every thousand people on my Instagram feed will say, ‘Bring back The Cardinals,’ and I don’t respond because my actual response would be like, ‘Which fucking version?’” he says. “I didn’t like any version of The Cardinals besides the first one. People go, ‘It’s not cool when you dislike the Neal Casal-era Cardinals!’ And I’m like, ‘Well, I only wrote all the fucking songs! So maybe I am actually [allowed] to say that they suck.’ And also, Brad [Pemberton, the drummer] and I, in The Cardinals, didn’t ever see eye-to-eye about how it’s supposed to sound. Brad played on Cold Roses, and the only reason he’s on it is because I made him play with brushes. I played the rest of the drums you hear on Cold Roses songs like ‘Life Is Beautiful.’

“Brad doesn’t listen to the Grateful Dead; he listens to The Clash,” he continues. “And what I love about that loose-sounding, groovy Dead sound or Black Flag or Sonic Youth is when the rhythm comes undone. I love that first Jerry solo record because so much of it is undone, and its tempo is weird. But by the end of The Cardinals, Brad and Chris [Feinstein, the bassist] had respectfully decided that they wanted to sound like a huge rhythm section, so parts got really flattened out, and it’s not what I wanted.”

Adams met Yurco through his former bassist Catherine Popper. A veteran of both The Cardinals and The Nocturnals, Popper suggested that Yurco reach out to Adams during this recent, trying period. Adams describes his current guitar foil as “the fuckin’ sweetest, coolest, Zen-est—just such a bro.”

Yurco called Adams “out of the blue,” and they had a “beautiful conversation full of musical distractions.” They quickly realized they shared a love and respect for the Grateful Dead and Black Sabbath, as well as iconic alternative artists like The Smiths and The Cure. They also bonded over pinball.

“If you want to understand how he plays guitar, watch him play pins—when he solos, he’s in total multi-ball mode,” Yurco says. “I actually acquired my very own pinball machine as part of my process of learning Ryan’s material. It is now a permanent fixture in the living room and, in between learning Ryan’s songs, I take a break to play a couple rounds of pins to give me perspective. That’s the PAX-AM way.”

To read the rest of this article as well as features on Robert Randolph & the Family Band, Greensky Bluegrass, Keller Williams, Real Estate, Holly Bowling and others, subscribe here.