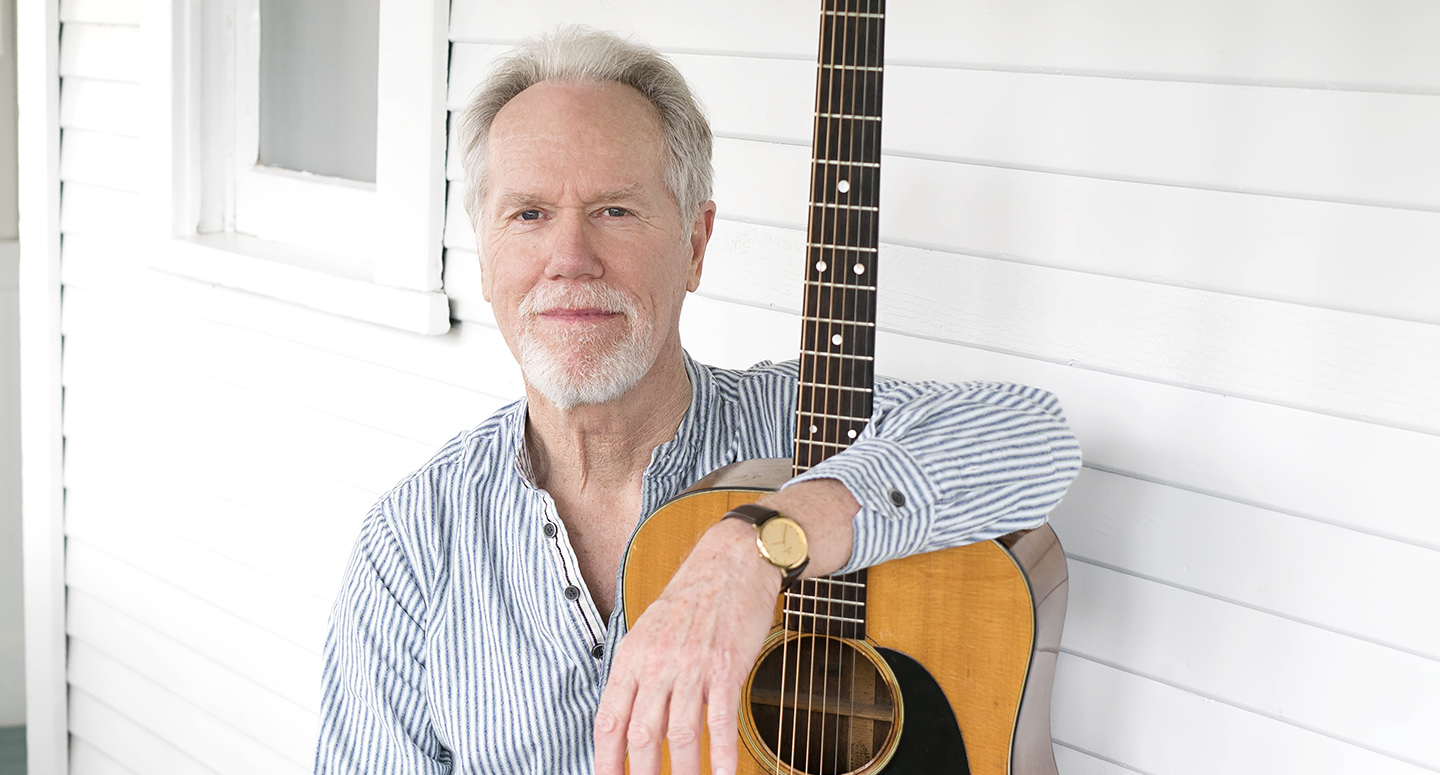

Reflections: Loudon Wainwright III

The old “New Bob Dylan” puts his life in order on a deeply personal, comfortably cluttered studio set and new Netflix special.

Sex and death figure prominently in Loudon Wainwright III’s 28-album discography. So do his children, his father issues, his mother issues, his drinking, his philandering, his life on the road, his thoughts on current events and his offhandedly stunning ruminations on life as it’s lived day-to-day and year-to-year. Loudon’s songs tend to naturally fall into such silos, and he has more of these categories than nearly any of his peers in the singer-songwriter pantheon.

The past two years have been a time of reflection and collection for the 73-year-old musician and father of talented siblings Martha Wainwright, Rufus Wainwright and Lucy Wainwright Roche. In 2017, he published his memoir, Liner Notes: On Parents & Children, Exes & Excess, Death & Decay, & a Few of My Other Favorite Things. In 2018, he released Years in the Making, a two-disc collection of musical odds-and-sods from his nearly five-decade long career. Most recently, Loudon dropped his one-man Netflix special, Surviving Twin, a “posthumous collaboration” with his own father. Loudon’s songs alternate with his dad’s essays, and the two ultimately merge when Loudon steps into his father’s pants, if not his shoes.

Lineage issues run thick in the Wainwright tribe. Loudon’s father was an editor and popular columnist for Life magazine at a time when magazines were mass-culture influencers, and the son was an admittedly “furtive” reader of his father’s famous column, “The View From Here.”

“I didn’t really like having a famous father with the same name,” Loudon says. “It wasn’t cool. He and I were not ‘close,’ to use that fun word people use, but we were kind of the same guy.”

They’ve become much closer since Loudon Jr. died in 1988 at the relatively young age of 63. After stumbling across “Another Sort of Love Story,” a column about having to put down the family dog in 1971, Loudon III was inspired to develop a one-man show around his father’s writing, which has “moved and affected” him since about the time he turned 63 himself. Loudon performs some music from his 2012 album, Older Than My Old Man Now, in the show, which debuted in 2013 and came to Netflix through producer Judd Apatow and director Christopher Guest, whose film and television projects Wainwright occasionally appears in.

“Loudon Wainwright III” is a constructed character, of course, and acting was one of his early passions. Although he dropped out of the Carnegie Institute of Technology’s drama program to “go to San Francisco and take drugs,” Loudon nonetheless snagged the role of singing surgeon Captain Calvin Spalding in three early-‘70s episodes of the hit TV show M*A*S*H. While he wrote and performed songs about General Douglas MacArthur and North Korea during his brief run, he often has to remind people that he did not write the show’s theme song. He’d be rich if he had. But the bleak, even Loudon-esque lyrics to composer Johnny Mandel’s “Suicide Is Painless” were, in fact, written by director Robert Altman’s 15-year-old son, Mike.

Loudon’s musical career has been a long autobiography. Which made interviewing him—holding forth in the enviably roomy and comfortably cat-inhabited prewar apartment he shares with New Yorker magazine editor Susan Morrison—a little weird. Nearly everything you’d want to know about him is in the songs, if not his eminently readable memoir.

He has always interspersed goofy novelty numbers like “Dead Skunk,” the throwaway track that earned him riches and fame in 1973, with more serious, even dire, ruminations.

Loudon acknowledges the existence of “camps and certain people who would prefer that I not goof around in song; or would prefer that I lighten it up a little bit, I’m sure, too. But what are ya gonna do? Fuck ‘em if they can’t take a joke.” More often his songs blend comedy and tragedy into something uniquely Loudon-ish. And once he found his footing as an essentially autobiographical songwriter with Album II, ‘twas ever thus.

Although Years in the Making has the feeling of a cluttered closet, its relative disorder has a purpose. Having survived into his 70s, Loudon finds himself “in the process of putting my life in order. So I was going through stuff anyway, organizing things.” He extracted reel-to-reel tapes, cassettes, CDs, club board mixes and other media from a room containing “loads of crap” in his house on eastern Long Island. The resulting laptop demos, bootlegs, studio recordings and live recordings were sequenced into “chapters” with the help of producer Dick Connette.

“I’ve written a lot of songs about my kids,” Loudon says, “and kids in general, so that was an obvious chapter. I’m not a folk musician, but the folk boom of the early ‘60s influenced me, and I play an acoustic guitar, so a folk section made sense. But I also dabbled in bands, with varying degrees of success, so we picked some things and created a ‘rocking out’ section. Then there were the topical songs. The ‘Big Picture’ chapter is about not just me, but us and the world.”

Like many of his peers, Loudon oscillates between reckless narcissism and expiatory self-effacement. When asked if any rediscovered material on Years particularly delighted him, he refuses to play along in a can’t-pick-a-favorite-child sort of way, adding, “I’m always delighted to listen to me, of course; I’m always delighted by me.” But he also feels that while the guy in the songs is, most definitely, a version of him, he’s singing about issues that pertain to everyone, hence his appeal.

“Other than the goofy novelty songs, or the topical songs, a lot of my songs are about my life and the people in my life. I don’t hide that. They’re the interesting people in my life, so why not write about them? But the songs are condensed, worked on and edited; stuff is left out and stuff is thrown in.”

The specificity can sometimes be overwhelming. During a fractious marriage to Canadian singer Kate McGarrigle, Rufus and Martha’s mother, Loudon and his wife jousted emotionally via their songs. When Loudon’s “Rufus Is a Tit Man” copped to jealous feelings about his nursing son, McGarrigle replied with “First Born.” “He’s his mother’s favorite and his grandmother’s too/ He’ll break their hearts, and he’ll break yours too.” (Much later, when daughter Martha recorded “Bloody Motherfucking Asshole,” Loudon didn’t realize he was the song’s subject until his daughter announced it onstage while opening for him.)

Many strands of the Wainwright saga entwine during Years in the Making’s highlight, “Meet the Wainwrights.” The family sang the sort-of-a-polka tune during a five-show Alaskan tour, when the clan traveled on a train, boat and bus with dozens of their fans. “They saw us in daylight!” recalls Loudon in mock horror. Rufus (“he’s more famous and much richer than the rest of us”), Martha (“happily is here/ Although there are some times Martha chooses to steer clear”) and Lucy’s mother, Suzzy Roche (“once upon a happy time I slept with Lucy’s dad”) all get their moment. But Dad gets the final word, clarifying that “if it were not for Loudon, none of you folks would be here.”

Loudon addresses his Oedipal issues regarding Loudon Jr. in songs like “Your Father’s Car” and “Surviving Twin.” Things get more uncomfortable in “White Winos,” where a few drinks with mom elicit the other side of the Oedipal equation. Rufus later joins in the fun with “Dinner at Eight,” in which he decries Loudon’s paternal failings and warns, “No matter how strong/ I’m gonna take you down.” As hard as their family shit may be to swallow, the Wainwrights, nonetheless, lay it all out on the table.

One might argue that Loudon adopted his father’s style early on. He made his first record in 1969 and, although he’d already dropped acid in San Francisco a few years earlier—“with long hair and all the accoutrements”— onstage, he assumed a straight appearance more familiar to his father’s generation. “I adopted my boarding-school look,” he explains, “kind of a preppie psycho killer. Everybody else had long hair and bell bottoms, and all of a sudden a guy walks up with a button-down shirt, gray flannel slacks and short hair. People thought: That’s different.”

Thanks to another conscious affectation, a tendency to gurn and thrust out his tongue spasmodically while singing, he came to resemble the Gene Simmons of folk music. “I once made a record at the Record Plant in LA, and KISS was next door,” he recalls fondly. “Wow, that was quite a week.” Now he chalks up the tongue wagging to early performance angst. “I am shocked by the grimacing and facial contortions when I look at YouTube videos of me at the beginning of my career,” he admits. “But I was terrified, and I think physicalizing the fear lessened it.” He currently thrusts out his clapper mostly, it seems, for old time’s sake.

When it comes to performing, Loudon has nearly always been a “one-man guy,” as he has put it. “Part of the reason people think of me as a solo singer-songwriter is the economics,” he explains. “I don’t have to pay the bass player. It’s self-contained.” But when the opportunity arises to play with other musicians, particularly great musicians, Loudon grabs the chance. After fleeing to England in the mid- ‘80s to escape a relationship gone south, he recorded a pair of fine albums with Richard Thompson. I’m Alright and More Love Songs set many of Loudon’s best songs to crafty, rocking and vintage arrangements jazzed up with Thompson’s mighty guitar. Mercurial jazz twanger Bill Frisell likewise drifts through most of 2005’s Here Come the Choppers, and he can also be heard live with his trio on Years’ heartbreaking divorce ode, “Your Mother and I.” Loudon’s own instrumental skills are usually underrated. He started playing guitar when he was 13 and still adheres mainly to the laid-back, flatpicking style of his “guitar hero,” Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. “I’m proficient, certainly,” he says, “but it’s just from playing the same five chords for 60 years.” He does a little finger-picking, blues, country, rock and jazz, too. “It’s not developed, but it is solid,” he says. And when it comes to the obligatory solo bit in the middle of a song, “I keep my instrumentals short. I know my limitations.” The old “new Bob Dylan” currently doesn’t emulate his elder’s touring style. Going to the airport, hauling his guitar through security, renting a car—it’s all a “slog” at this point. “I hate to bitch about it but, man, it’s tough when you get to be this age.” Once he’s onstage, though, Loudon lets the good as well as the bad times roll with as much pathos and humor as ever. Since he’s already written that it’s probably necessary to feel like shit in order to be creative (“unless you’re J. S. Bach”), Loudon Wainwright III shouldn’t have any shortage of material as time takes its toll.