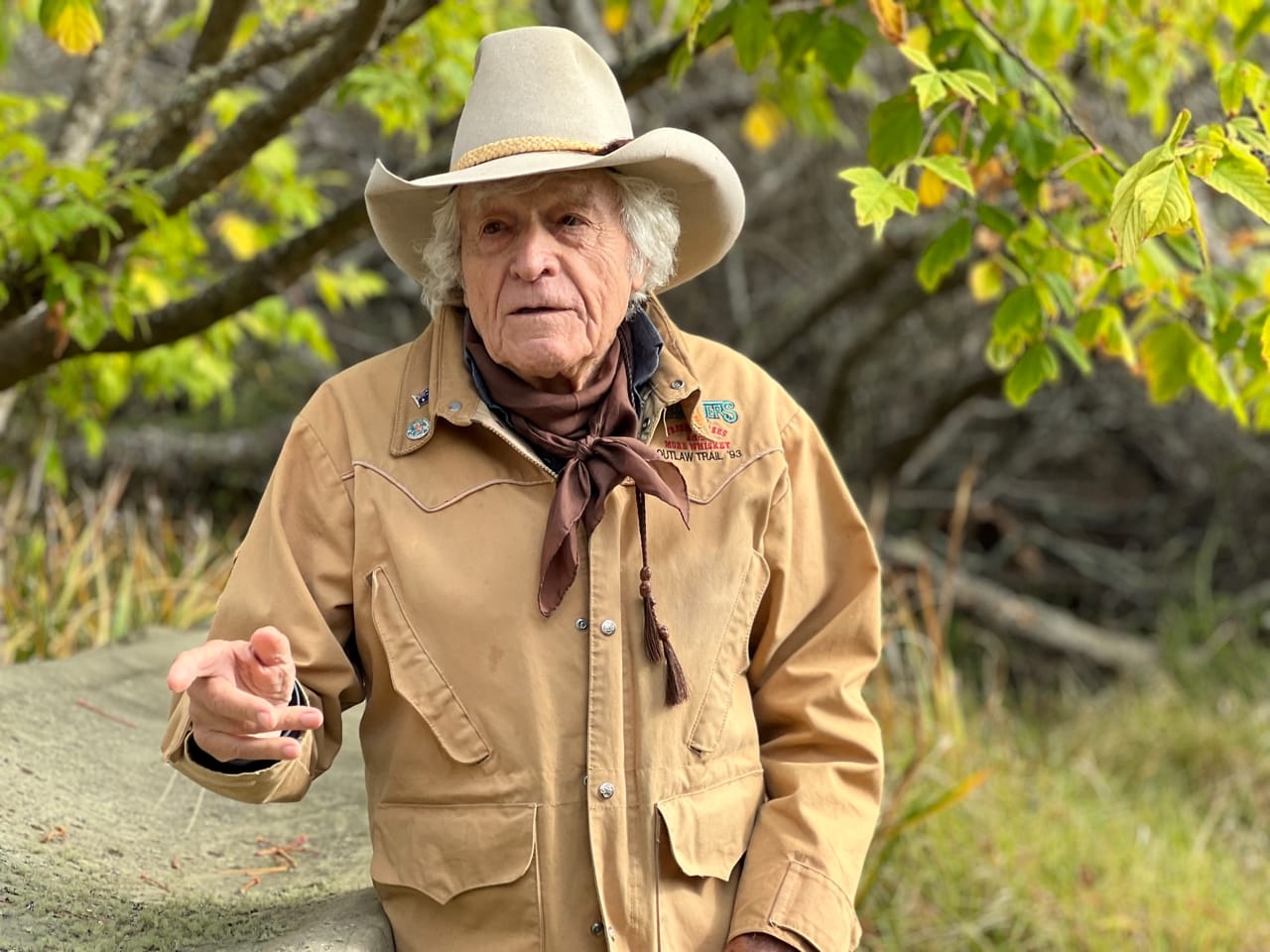

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott: The Eternal Troubadour

photo: Aiyana Partland

***

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott loves to tell the story of how he and Grateful Dead co-founder Bob Weir first met. In 1963, Elliott had just performed at the Cabale Creamery in Berkeley—it was an opening slot for blues legend Lightnin’ Hopkins. After the set, he returned to the green room to relax and tune his guitar.

“I looked up and saw this unknown person—a tall, good-looking young man—drop down from the skylight,” Elliott recalls. “Like God came down from the sky.”

Initially, he thought it might be someone connected to a motorcycle he had “borrowed” and was planning to drop off the following day.

“I asked him if he was Bill, the person with the motorcycle,” Elliott says. “‘No,’ he said. ‘I’m not Bill; I’m Bob.’ Then, he asked me if I had anything. He was looking for something or other, and I said, ‘No.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about.”

At the time, Weir was too young to get into the show, so he had shimmied his way up a drain pipe onto the roof of the Cabale during Elliott’s performance. He then pulled the lid off the skylight and dropped down into the building— specifically, the green room where Elliott had retreated when it was time for Hopkins to go on.

“Bob is generally a shy person,” Elliott says. “He was 16 years old, and I was 36. I don’t remember hitting it off at all.”

The meeting might have been somewhat anticlimactic, but it represents how people seem to fall into Elliott’s life—yet rarely does anyone fall out of his life. He wouldn’t meet Weir again until the Grateful Dead was in full force, but 60 years after the two first crossed paths, Elliott considers him “one of my closest friends in the world.”

As Weir walks onstage to join Elliott, drummer Jay Lane and bassist Paul Knight during a late-November 2022 show at his Mill Valley, Calif., joint, Sweetwater Music Hall, it’s evident that the sentiment is mutual.

“He’s uncompromising in his dreams and romantic notions,” Weir told Relix in 2016, citing Elliott as one of his heroes. “He was a Jewish kid born in Brooklyn who learned to be a bronc rider. And somewhere along the way, he picked up a guitar and became a troubadour.”

***

Ramblin’ Jack was burn Elliot Charles Adnopoz to Jewish, upper-middle class, Lithuanian immigrants in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood. His father, a respected surgeon, envisioned him attending a top university. But the open road—and the freedom it represented— beckoned Elliot from an early age. He was seduced once he got a whiff of the rodeos that came to Madison Square Garden and read about the American cowboy in novels by Will James. At 15, he left New York City and joined the J.E. Ranch Rodeo, where he experienced a singing cowboy and a rodeo clown first hand. Not long after skipping town, his parents found him and brought him home, but it wasn’t all for nothing. Elliott taught himself to play guitar shortly after, and his vision of who he was and where he wanted to go became clear.

Elliot reinvented himself and left his New York City roots behind; he was a mysterious cowboy without a backstory. He adopted the name Buck Elliott before transforming into Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and he rolled with the breeze like a tumbleweed, ending up wherever the gust took him. Along the way, Elliott discovered a lasting love for GMC and Peterbilt semi-trucks, everything nautical and picking on a $12 Collegiate guitar made out of cigar box wood. (Elliott’s mother bought him the guitar when he was 13 before he had any interest).

During his travels, interactions with new friends served as his true education. More important, these connections have led to an endless stream of content, propelling a limitless supply of stories. As The New York Times wrote, “He has covered, befriended and worked alongside American folk icons for so long that he’s become one.”

Elliott was 19 when he hooked up with Woody Guthrie.

“Woody didn’t teach me,” Elliott asserts. “He just said, ‘If you want to learn something, just steal it—that’s the way I learned from Lead Belly.’”

Guthrie’s guidance, as well as performances by the likes of Bessie Smith and Cisco Houston, helped Elliott develop his own style of fingerpicking. When Bob Dylan first arrived in New York from Minnesota, seeking direction from Guthrie, it was Elliott—who had just gotten back from Europe, where he spent several years busking with his wife June, logging thousands of miles on a motor scooter with his guitar slung over his shoulder—who took him under his wing and taught him everything he knew.

Photo courtesy of Jack Elliott

Elliott has always been in the right place at the right time and kept the company of extraordinary people. It’s like when Weir literally dropped into his life after the Berkeley show. People fall into Elliott’s company, or vice versa, and chance encounters become lifelong friendships—or, at the very least, unforgettable stories. That was certainly the case when Elliott and his then-girlfriend were invited to an unknown writer’s apartment to listen to him read the manuscript he had just finished, On the Road. (Jack Kerouac’s Beat classic wouldn’t be published for another four years.)

Another time, Elliott was invited to hang out with Mick Jagger in Toronto. The Rolling Stones frontman told Elliott that he remembered him performing for him and his school friends at a train station in Dartford Kent, England when Elliott was bumming around Europe.

“I saw the children waiting, so I got the guitar out and played a couple of cowboy songs,” Elliott says. “Of course, I always wore a cowboy hat. [Jagger] told me he went out the very next day and bought himself a guitar. He said he wanted to be like the guy with the cowboy hat and guitar.”

Johnny Cash included Elliott’s “Cup of Coffee,” which he dubbed the first trucking song ever, on his 1966 record, Everybody Loves a Nut. Elliott is featured on the recording, showing off his yodeling ability.

“Nobody I know, and I mean nobody, has covered more ground and made more friends and sung more songs than the fellow you’re about to meet right now,” Cash said before Elliott’s 1969 appearance on The Johnny Cash Television Show. “He’s got a song and a friend for every mile behind him.”

photo: Adam Joseph

Over the years, Elliott has performed with everyone from Nico to Steve Earle and John Prine. Last year, at 91 years old, Elliott joined Weir at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium to perform Prine’s “Great Rain” as part of an all-star celebration of his recently departed pal.

Meanwhile, depending on the day, Elliott would rather be on a boat or driving a truck than performing.

“I’ve driven about 40 semis over the last 50 years as a hitchhiker, a passenger and a part-time driver,” he says. “I had a long dream about riding in a truck with a guy, and we were pulling a strange trailer that was not securely hitched. It was sort of like pulling Yugo on the end of a rope. Sometimes, we look in the rearview mirror, and the trailer was in another way, which, of course, is extremely dangerous. So, it was kind of a dangerous dream. But the truck I was riding in was a beauty. And the driver was about to let me drive it toward the end of the dream. Perhaps I was fortunate that the dream ended before I took the wheel.”

***

“Jack never tries to be anything but who he is,” says actor/author/artist Peter Coyote, who first met Elliott as a teenager on Martha’s Vineyard. “It’s that authenticity that just surrounds him like a glow. He’s charming and a great fucking storyteller. Jack was, and remains, a true touchstone for a kind of Bohemian authentic raconteur. Jack is one of the last throwbacks to the pure strain of the Beats. We forget Jack loves cocaine and fucking. He’s not a simple folksy dude.”

Money and fame have never been motivators for Elliott. That would be too simple—boats, diesel semi-trucks, ranching, friendships and the freedom to live as he sees fit are more important. They’re also the traits that Norwegian-born Americana singer-songwriter Irena Eide, a.k.a. Rainy Eyes, values most about Elliott. She’s toured with him several times over the last 15 years.

“He appreciates hard work like farming and ranching, and he loves boats and how they’re built and all the different parts,” Eide says. “He has so much knowledge and an incredible memory. I’ve learned so much from him. He makes me think about things differently, too. He’s taught me a lot about performing, connecting stories and songs—and how to do it in a way where it becomes just one big song. I love listening to him talk, tell stories and show his appreciation of boats, how they’re built and all the different parts.”

“912 Greens,” one of two songs Elliott is credited with writing—“Cup of Coffee” being the other—beautifully captures his capacity to blend story and song into one seamless and enchanting entity. As he delivers an airy backdrop of his trademark flat-picking, Elliott unleashes booze-soaked prose to sculpt a humid summer night in New Orleans from a bygone era. The simple details equate to expressive brushstrokes as Elliott talks his way through the tune: “And a gray cat with three legs named Grey that used to lope along and fall down/ ‘Cause Grey he had a stroke, couldn’t run too good on them three legs no how.”

Revered by Jackson Browne as a “time-traveling, spoken-word masterpiece,” “912 Greens” closes with a single line of singing: “Did you ever stand and shiver, just because you were lookin’ at a river?” The open-ended question doesn’t solicit an answer. However, it resonates with listeners and has led to some lofty awards.

He’s won a pair of Grammys and a Folk Alliance Lifetime Achievement Award, and is a National Medal of Arts recipient. Elliott is also featured in Martin Scorsese’s film Rolling Thunder Revue and the PBS release of Woody Guthrie All-Star Tribute Concert. He even has a coveted seat at the Woody Guthrie Center Theater in Tulsa, Okla., alongside icons like Pete Seeger and Lead Belly.

Additionally, his daughter Aiyana Partland’s 2000 documentary, The Ballad of Ramblin’ Jack, earned a Special Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival. The Austin Film Society recently screened the movie, with Elliott and Partland in attendance, last April.

While Elliott’s wild days might be over, the folk musician is still most content when he’s on the road, touring, rambling, doing what he loves most. He’s been doing so nonstop for over 70 years and is the last of the 1950s folk revivalists. Elliott recently turned 92 and has no plans to retire. In September, alongside a lineup that included both Chuck D and Anders Osborne, Elliott participated in the Park City Song Summit in Utah, followed by shows scheduled through December, including an appearance at the Brooklyn Folk Festival that will celebrate 75 years of Folkways Records.

Looking back on everything, Elliott has only one regret and it has nothing to do with music: “I regret that I never sailed around Cape Horn when I was young enough to do it.”