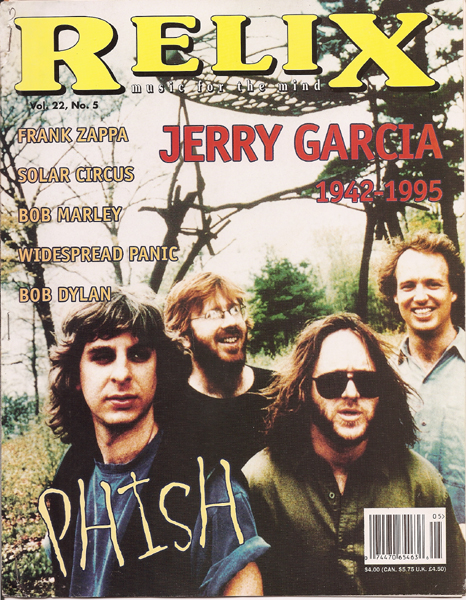

Phish, No Fear Of Flying: An Interview with Mike Gordon (Relix Revisited)

Here is part one of an extended conversation with Phish bassist Mike Gordon, conducted by former Relix editor Toni Brown for the October 1995 issue of the magazine.

You’ll have to forgive me – much of my reference is going to come from the Grateful Dead. But I see you as being the next progression, except that I can’t compare the music, which has transgressed to a more complex level. The Grateful Dead has always been a jamming band. A lot of the bands that have been influenced by the Grateful Dead jam. Other bands out of the ‘60s era jam. But you guys take it to another level.

Mike Gordon: Yeah, it’s different. I think it’s exactly what you say. It borrows on some of the same philosophies as well as philosophies from other groups. You know, there’s the Frank Zappa influence and groups not found in pop music, but in other styles. But it takes a certain philosophy of jamming, in allowing the music to be, allowing the group mind to develop and the music to take on its own thing where the individuals aren’t controlling it, which the Dead definitely believe in. It adds a consciousness where some of the jamming is on more of a conscious level, and we’re making decisions, as a band, to suddenly switch the jam in a different direction.

We actually practice jamming exercises, and I think it’s the sort of thing that the Dead have never believed in – to practice jamming. But, with us, we’ve found that it’s listening exercises because, if a gig is good, it’s always that we’re hooked up as a unit and we’re listening to each other and are very aware. If it’s ever a bad gig, it tends to be when different band members are in their own worlds and aren’t aware of each other. So we do exercises in our practice room at home to make sure that we can hook up and that each person can hear each band member and react to each other. As a result, if we’re jamming, it’s possible that we’ll suddenly change the tempo to three times the speed, switch keys, and go off on a different… someone once described it as a herd of buffaloes that were going fast through a field and suddenly took a left turn together. But there are other people who actually described it, this sort of new direction in improvised music that we’re taking, as being sort of the coming together of a Dionysian and Apollonian values where the ecstasy of the Dionysian ritual is combined with the consciousness and thoughtfulness of the Apollonian ethic and combined into a new art form. In terms of modern music, some people have said that’s what’s happening with us.

There’s an intense intellect, a complexity to your music.

Gordon: Yeah. There are sections of songs that are written out that are fugues. Trey, who writes a lot of our music, worked with a composer, his mentor, for six years. For one or two years, he worked on an atonal fugue. And then, when it was done, it was plopped in the middle of a song that we do, so one section would be memorized. Now that we have six albums out and a lot of songs that aren’t on albums, before we go out on a tour, not only do we practice jamming and get our mind sets in gear and write new songs, but we each have to take the six albums and relearn all the worked-out passages. So we try to stretch as many limits as we can. One limit is the limit of improvisation where it’s completely free form or into the other end of the range, where it’s completely memorized and not a single note improvised first.

So you basically start something and have the skeletal idea of what you want to do, and then you’ll just take it to whatever level is comfortable for that moment.

Gordon: There are different situations for each song and for different parts of songs. The idea of taking the skeleton and building on it would apply to most of the songs, but the situation would range from chord progression where there would be maybe a solo or us jamming on a chord progression, and we’ll see where that goes. That’s kind of in the middle where there’s structure with improvisation together. But there are situations where there are jams where we start them, knowing it or not, and even the building block itself is improvised. Someone will just start doing something, someone will play a riff, let’s say, as soon as a song’s over, maybe, or in the middle section of a [song], and we’ll realize that this doesn’t normally happen in this song and that the cosmos are pulling us toward complete spontaneity, towards something new. The other band members will go along with that, and it’s really tricky.

Not to get too philosophical all at once, but one question that came up recently is that, if we’re in a song and something’s gonna happen that’s never happened before in a radically different way, what is it that’s going on in my mind, and in our minds, that makes us decide to take that different route? In that situation, that sort of thing could happen where we’re gonna go on a tangent that’s completely unplanned. Like a song that’s normally five minutes is now gonna be half an hour or however long it wants to be, and it’s not gonna be that song anymore. It’s not just gonna be noodling where we’re throwing out notes meaninglessly to make a disconnected wall of sound, unless that’s the specific goal. Unless we want to have a big wash of sound, which is cool, but whatever it is, ideally it will be deliberate where we are together. That tangent, whatever it is and however demented or however pretty it is, is a group mind sort of thing.

“What puts us in a certain direction?” If I’m standing on-stage and I’ve forgotten to swallow for five minutes because I’m so absorbed in the music – sometimes I believe in this egoless thing of playing two bass notes for twenty minutes and not trying to make up a cool bass line, but just letting it be a meditation. But then, if I add a third bass note within the bass line after twenty minutes, where did that come from? I came up with a sort of spiritual theory of where that comes from. There’s this book called Stopping The Wild Pendulum that my mother gave me. Kind of a metaphysical book. This guy never went to school past kindergarten, but he became a practicing medical doctor and a real one of those wizard-type people, and he makes all these postulates in the book. Some were sort of disproved later because they’re so crazy and others still hold, as crazy as they were. He has this theory, which can be modeled with a pendulum, that everything is waves, and that’s not a very uncommon metaphysical thought. A lot of people think in that way. But to look at a pendulum, the pendulum’s going at its fastest velocity when it’s in the middle of its swing. Its kinetic energy is the most, and its potential energy is the least. When the pendulum gets to the end of its swing, there’s a split second in time where it’s sitting there and it’s stopped. It’s about to go back in the other direction. The theory is that when the pendulum is up in that split or infinitesimally small moment where it’s waiting to come back in the other direction, that the kinetic energy is zero and the potential energy is infinite. I guess that’s the way people would look at it. His theory was that right at that moment, all the energy of the universe comes to that pendulum ball or it sort of stretches out. With its kinetic energy being zero, its other form of energy stretches out to the edge of the universe and makes contact with all of the other wave forms in the universe that are experiencing that moment of pendulum, or whatever you would call it. And then it comes back and returns to its normal swing.

My theory is that ideally, if music is a meditation, and if everyone is accepting the moment and has faith in the moment and in the music as carrying us without letting the ego get involved too much, that there will be those moments when I’ll be standing there and another note will appear in the bass line, if it’s a pattern, and it will have come from somewhere else. Music will sort of metamorphosize, and the other people will hear it.

People would have to be attuned to the moment to hear it. The stranger, the looser, the more intense and the more intricate that your improvisation gets, the more your audience seems to respond to it. I think that the last generation would get a little bored, sort of drift off. Talking to you right here and now, I sense that you could have been an astro-physicist or any technical thing you’d have wanted to be, but you’re a musician.

Gordon: I was actually an electrical engineering student for two-and-a-half years. [I have] the technical sensibility. Actually, the head of the electrical engineering department said that there were a lot of engineers that were bass players, according to what he had found. The funny thing about being a bass player also is the role that you’re filling is so functional. In a way, it’s the hardest to improvise on the bass because there are things you have to do. You’re the link between the rhythm and the harmony, so to be functional and to be so free that the music can go in any direction at the same time ends up being a big challenge.

Lately, I’ve been in a really good frame of mind. The beginning of the tour I was a little bit frazzled thinking about equipment too much, changing instruments a lot. At one point Trey said, “The whole organization is suffering because of your trying out these new basses and switching them. Paul can’t get the sound right because he cues in on one and then you change.” And I decided I better just think about music. I better just think about nothing and allow this other stuff to happen and free that left side of the brain which, in my case, keeps going on and on. But lately, I’ve been really just allowing the beat to be, even if it’s a beat we’ve played before, not worrying about having it be something new necessarily. Not worrying if it’s too new, or whatever weird thought come into my mind, and hooking up with Fish, the drummer. For years we had a loose low end, and he always considered himself to be a jazz drummer more than a rock drummer, which is hard for a bass player who’s trying to be a rock bass player ‘cause the role is so different. But lately, it’s a great feeling for me to be hooked up with the kit drums and having my mind be attached to this musical machine of sound from the underneath, sort of from the engine room. It’s that kind of technical engineering thought process – being the helmsman of the ship – whereas Trey would probably be the person steering in front or on top, doing the guitar lines that sit on top. I kind of like being on the bottom, in a way.

Your improvisation links you strongly to jazz.

Gordon: We did try to play jazz. We actually had a jazz ensemble with local horn players from Burlington, our home town. Every week we would play at the café just to try to learn some things from the horn players. We’ve listened to a lot of different jazz from different areas. We listen to a wide variety of music. There was a period where we tried to learn the style of certain eras of jazz. I think that what ends up happening is the sound is a more rock ‘n’ roll sort of sound and some of the ideas of improvisation might come from jazz. Jazz is such a wide spectrum that it’s hard to generalize, but often a jazz band will jam over changes – a certain structure. They’ll play the melody, they’ll play the head and then they’ll jam and then they’ll come back and play. Maybe they won’t have any changes. Like modal jazz. Miles Davis will just jam on one chord for an hour.

What we try to do that doesn’t often happen in jazz, or in any kind of music, is not only to improvise on top if the structure or instead of the structure, but actually to improvise the structure itself. It’s like spontaneous songwriting in a way. It’s not often that verses and choruses will come together entirely unstaged, but a chord progression might develop and textures might sort of move in sections and some words might be sung spontaneously. So that’s not exactly like jazz, that’s something different. I don’t know what it is.

Your music is very elaborate, but many of your lyrics are somewhat repetitive. Is it fair to say that you put more focus on the musicianship than you do on the actual structure of the lyrics? In the lyrics, it seems like you’re going for the sounds and textures of the words as opposed to the actual meanings of the words.

Gordon: The lyrics have gone through changes over the last few years. Most of our lyrics are written by Tom Marshall, a friend of Trey’s from before high school. I’ve written maybe ten of our songs, and Trey himself has written a bunch. But most of them have come from Tom and Trey working with Tom. The words came from the wordplay where the syllables and the way they sound are as important as what they mean – little phrases that might be a little intellectual and emotional triggers, but the way they connect together is real up-in-the-air for interpretation. Our albums, especially our first three albums, reflect that. If you can make sense of the lyrics then it’s a real fantasy world with strange characters. At a certain point, we really wanted to sing about something, things that we could sink our hearts into and really believe. I think when you say the musicianship has been more significant in our career than our singing, we’ve actually worked with singing teachers and we had a barbershop quartet teacher for a while, different people and different concepts. We’ve read things about singing, and it’s been an effort to try to catch up the singing to the musical side of things.

In a 20-minute song which has five words, those five words are much more meaningful than are some with a hundred words. A few albums ago, we wanted to sing music that we could feel more, and there was an effort to write things that were a little bit simples and easier to grasp onto and about real, serious subjects. If there was a turning point, it might have been Rift, which is loosely a concept album about someone sleeping at night dreaming about his girlfriend, and the rift is a rift in a relationship as much as anything. Ideally, lyrics will have meanings on different levels, but that was roughly the concept. And all the songs fit together in that scheme. Actually, on the cover, there was a huge oil painting done by a guy with all the songs reflected, drawn into the painting symbolically. It was kind of a heavy and dark album. After it was over, we decided that we still liked the idea of lyrics having meaning that you could grasp onto, but we wanted to make an album with shorter, songier songs.

Well, Junta was that. It was actually your first recorded project, though it wasn’t released until later by your label, Elektra.

Gordon: We really feel like there’s something nice about that stage. In some ways, some people like it the best. It has more of a youthful innocence in the way that the songs are patched together, different clumps sort of shoved together almost randomly. Like “You Enjoy Myself” has 20 different sections, and there is a flow in the song, but it’s not very maturely put together. A lot of the lyrics are, I think, the old style lyrics for us where it’s just word play, maybe with a couple of exceptions. But then we did Hoist, our fifth album, and again, you can much more easily listen to the lyrics.

The name Phish conjures up the image of water. There’s a lot of imagery in your lyrics. But water seems to be pervasive.

Gordon: Well, Trey is the main songwriter, and I know with him, that he fantasizes a lot about floating, whether it’s in the air or in the water. I think it’s that kind of motion. Even when we’re not singing, I think maybe the improvisation has an underwater sort of feeling to it sometimes. A lot of times on-stage I have these feelings of motion. If the groove is really happening, it can feel like flying through the air. My theory about that is if you were really flying through the air, if [your] hang glider or whatever was actually bringing you through the air, the feeling of that, well, it’s physical but it comes into the brain as perceptions. So why not argue that you can be standing perfectly still and somehow have those same perceptions? That’s been a theme in my dreams, too. In dreams, I’ve been flying a lot, but I’ve been doing this new thing where I try to convince myself that it’s okay to fly up even though gravity is going on because gravity isn’t real in the dream. So I’ll fly up and look over the whole neighborhood and then go higher and look over the whole city and then swoop down and crash into a building and talk to people and go back up. But I think that we sort of fantasize about motion, and it’s real interesting to me the way that motion will change when the bass line changes.

Technically, if you look at a rhythmic pattern, we do a lot with rhythmic patterns, changing one accent or one syncopation will make the feeling of motion very different.

A bass is like and anchor, so it’s going to change the feel of movement.

Gordon: It changes the feel of movement, and it does it in different ways. There’s a way of playing where you can forget about scales, just think about going up and down or fast and slow. We do our listening exercises sometimes where we just improvise on tempo or texture. With the bass, for me, it’s an ongoing experiment. If I’m playing, I’ll play another note and just see what it does emotionally in terms of the group.

But what we were talking about is the underwater thing. I think that’s what it is. It’s probably a fantasy. Trey actually does a lot of diving and scuba diving, which I’ve never done before. He knows what it actually feels like to be under there. I would actually like to try hang gliding, but I know it’s very dangerous.

All these ideas that I’ve been thinking about are sort of popping into my head, and I feel another tangent coming on. I’m good at going off on a tangent and remembering where I came from. Sometimes I talk about my peak experience in November of ‘85. We were playing for [a few] people in the middle of nowhere at Goddard College, and I’ve definitely grown since then and I’ve learned how to achieve those levels of consciousness in music and new musical levels since then. But I still consider that to be my peak experience. How transcendent it was.

So when I think about growth, there’s change and there’s continuity. I think that for me it’s important to remember that there is an underlying, universal thing that stays the same, and that there’s goal to return to it. In terms of growth and change, it’s an argument that comes up between me and Trey and it has for the whole 12 years. He and Fish especially say their philosophy is originality and innovation. That’s important to me, but the way that I define the musical experience is that it’s not actually an artistic experience for me. It’s not art that’s driving me forward, and [it’s not] being creative and innovating and trying to be new and original, which are artistic values. For me, it’s more of a religious thing, where surrendering to the moment, meditating, are the supreme ideals for me.

Recently, on the bus, [Trey and I] had what was actually a fierce [discussion]. I say fierce because we were raising our voices. We [usually] communicate really well, which has been one of our keys to success. But what the argument was about, and this will tie things together, I think, is Trey said, “You know, in some ways we’re a popular, happening, improvisational band in the ‘90s right now. It’s good timing for us – people are interested in improvised music and we’re selling out some good places and word has spread about Phish. And inevitably, what’s gonna happen is that another band’s gonna come along and despite all the ways we try to stretch limits with improvisation and the listening exercises and everything that we do, jamming in new ways, another younger band’s gonna come, and they’re going to do things that we have never even thought of doing. And we should accept that that will be another step in the evolution.”

Trey said it could take one year or it could take twenty years. He likes to say that because he likes us to be on our toes in terms of innovating. He said it there were an era where we weren’t writing new songs, weren’t trying new things, he would quit.

So we were having this argument about innovation and Trey, like I said, he wants us to be constantly innovating and constantly original. What my argument was is this thing about growth and even art. I’m on shaky grounds when I talk about the philosophy of art, but ultimately the argument gets to the point where I say my main reason for doing this isn’t artistic. I don’t even consider myself an artist in the truest sense because there are these things that supposedly make art higher – originality, art being for art’s sake and the fact that you can objectify it to be able to analyze it, and timelessness, the fact that it will stand the test of time. My favorite musical experiences are very timeful. They’re just the moment, and you couldn’t listen to a tape later and have the same experience necessarily. You might have a different experience that would be new to its own time. For me, it’s more of a religious thing and a meditation, and I was making this example. If you take a Zen Buddhist or someone who meditates, is the goal to meditate in a new way that people have never meditated before? Is that gonna be the best thing that that meditator can do? Probably not. The goal is to go down the path. Maybe they’ll discover their own path, but it’s a tradition and when they finally reach Nirvana, it’ll be the emptiness place where the individual is so gone from the equation that they couldn’t be called an artist really. They’re so one with the art.

Let’s say there is someone who invented a new hang glider and they got to be famous for that, and they invented a new way of hang gliding where they could do a certain kind of spin. And then later they got to be famous for that. Then they got to a certain age where they said, “This has been great, all this notoriety, but I love to hang glide and now I’m gonna do it the same way from now on. I have a house with a mountainside and I’m gonna just jump off that mountainside and maybe I’ll go a little but differently, I’ll twist a little bit differently one day, but really I’m just gonna head down to the pond in the same direction every day and this is gonna be my meditation. I might not make it into the papers as often ‘cause I’m not breaking world records and inventing new hang gliders, but it’s what I’m gonna do.” And then maybe there’s another hang glider that, until the age of 80, like Picasso, is inventing new ways of doing it, breaking new records, using new mediums, and let’s say that they’re both happy. Is the guy that’s changing constantly till the end of his life any happier or more righteous than the guy who at the age of 48 decides that he’s gonna do it the same way from then on?

I also made the example of my mother who’s a painter. She does art backdrops. Over the years, she has changed her medium. Now she paints on plastic. What if at one point she said, “I like painting on plastic, and I don’t think I’m gonna change from now on. Each painting will be a little bit different, like a snowflake, so I’ll still be exploring, in a sense, but I won’t be changing, I won’t be as radical but I’ll go through life still loving what I do.” Is that a crime? So this argument that’s been happening for 12 years, right about that point, we had to go and do sound check. We started to come to the conclusion that we agreed with each other. That what we were saying is the same thing from different angles, parallax I guess you’d call it. And that really, without any change, I might not be happy. That to me, change is important. To Trey, continuity is important even though we’re taking the opposite stance.

What if we had to be so original that we would never play the same song more than once? We’d write it, play it and it’d be gone. What if each night had to be so different that there would be no building blocks that would got from one night to the next? And he agreed that that would be the extreme. [What if] innovation was so important that every second had to be an artistic creation that had never been made before, which is the way that Fish used to make up drum beats. He always used to think that each song had to have a beat that was very different from any other song that we had. And over the years, now he’ll actually play a solid beat for a while and be happy with it.

After sound check, we got back together and we said that we both realized that continuity and change sort of travel together and they both are important and that both philosophies, and the fact that we take opposite stances, adds richness to the band. We look at things from different angles.

I took the whole question one step further by wondering why we took opposite sides, maybe just for the fun of arguing. I realized that I like to innovate. I’ll be on-stage and I’ll think, “Oh no. We’ve played this beat so many times before. It’s like this incessant babbling of rhythm that I’ve heard before. I want it to be something new.” And when I’m really meditating, when it really becomes the Zen thing for me, those are the times when I accept the beat how it is, even if it’s something I’ve heard before or even if it’s been going on without changing. So the idea of staying the same… I have so many inhibitions and things I worry about – does the bass sound good, do I look stupid up here (laughter) and sometimes I have these peak experiences and I realize how many of them go away. I never realized how many inhibitions were there that I never even thought about, worrying about [and it] suddenly slips away and I see that they were there and I get to one with the moment and just accept the beat, and so it becomes an acceptance of the continuity. It all kind of ties together, change and continuity.