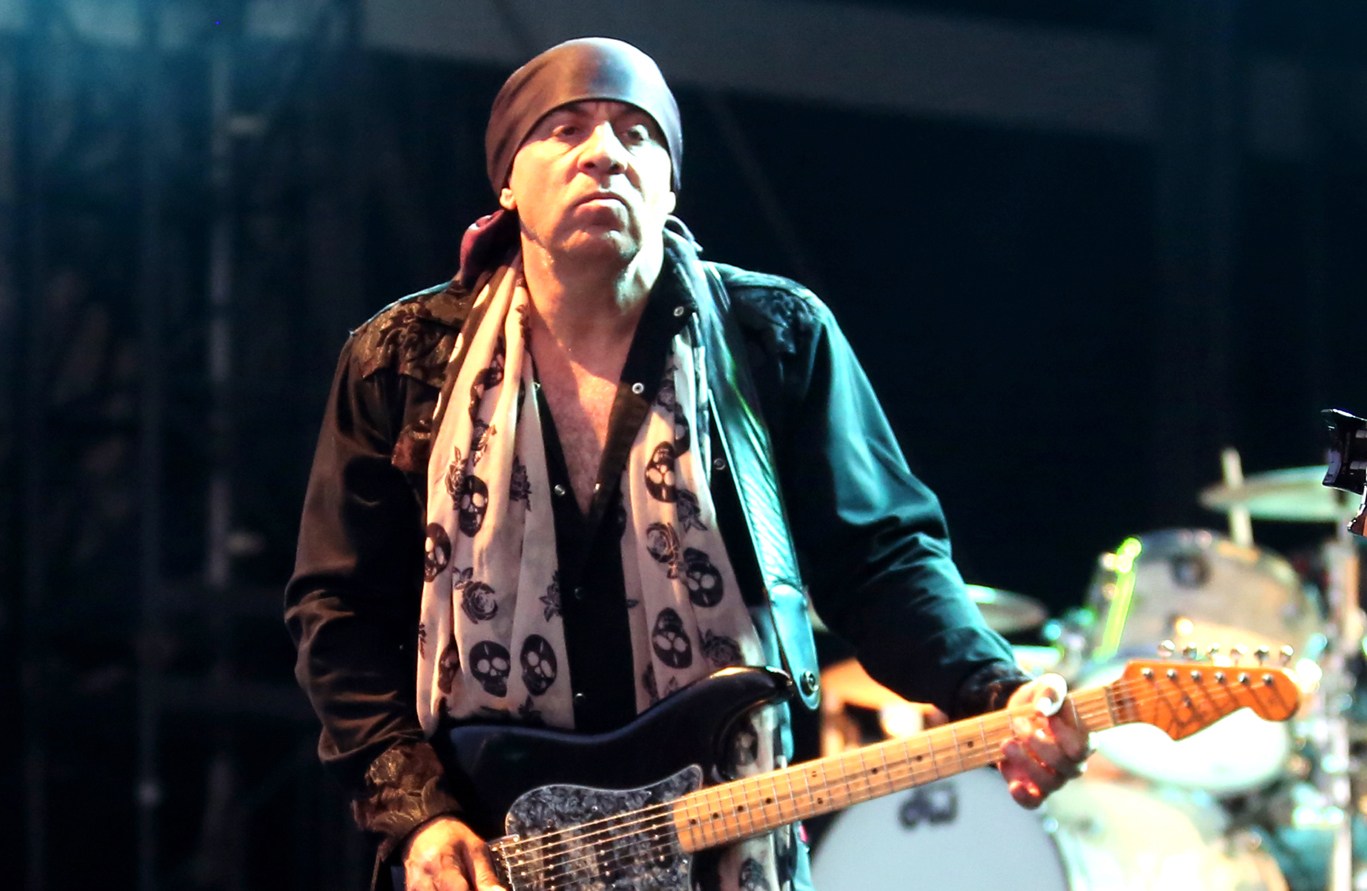

Parting Shots: Steven Van Zandt

Steven Van Zandt is a Renaissance man. This term is particularly appropriate because, as he states, “I don’t have much interest in the modern world, and I don’t pretend to.” Nonetheless, he remains an active contributor to contemporary American culture as the host of SiriusXM’s “Little Steven’s Underground Garage,” the co-writer and star of the Lilyhammer television series (following his extended run in The Sopranos) and his longtime post in the E Street Band, as well as his work with other artists (most recently The Rascals’ Eddie Brigati). He also just completed the new studio album Soulfire and will return to the road with his own 15-piece band, Little Steven & The Disciples of Soul, following the record’s release.

In describing Soulfire, you’ve said that you are now your own genre.

It’s important to find your own identity, and what I did was I created this thing between rock music and soul music. It was an interesting combination, and we did it with Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes, and I did it on my first album. Then, I got more focused on what I was doing, in terms of my political research and awareness. So the records continued to be conceptual and thematic but, musically, they varied according to what I was into at the time. They became artistic adventures, separate from each other while complementing the overall path. Now, this was very satisfying artistically but, career-wise, it was a disaster, and it was not something I’d ever allow anyone else to do if they were my friend. [Laughs.] You can’t have five different albums in five different musical genres. It’s not smart!

So, basically, I said, “I’m gonna make a new album. Who do I want to be? Who am I here?” I’m a lot of different people, and I decided to go back to what I feel is my single most identifying genre, which was rock meets soul—rock guitar with horns. And that was the way I decided to go and reintroduce myself to me, as well as whoever else was interested. [Laughs.]

You’re opening your tour in Europe. To what extent do European audiences respond differently to your music than American audiences?

We’re luckier than most—this includes my solo thing as well as working with Bruce and the E Street Band—in that our audience in America or Europe or Australia or anywhere else seems to be particular in their expectations and their dedication to what we do. It doesn’t seem like a casual relationship. Maybe it’s because we’re not casual guys. [Laughs.]

But, there are cultural differences. First of all, Americans tend to come to observe, and Europeans come to the show expecting to participate. That’s a very big difference in terms of how it looks, in terms of the basic optics. Now, it doesn’t mean one audience member is less into it than another; it doesn’t have anything to do with their passion or their love for the band or the music. It’s a cultural difference. Europeans are just into participating. So, you have 50,000-70,000 people in an audience in Europe, singing every single word, not only of the old stuff, but the new stuff as well.

There’s also a more integrated political awareness. The rock journalists in Europe are as politically conscious and politically aware as the political journalists in America. It’s in their DNA. It’s in their everyday lives because of their proximity to the other countries, the basic geographic circumstances, plus the history of the World Wars being fought there. Politics is very much a part of everyday life over there and, in America, it’s just not—although that may be changing now, a little bit. [Laughs.]

Your song “I Am a Patriot” continues to resonate, perhaps now more than ever.

That’s one of the most difficult songs I’ve ever written, first of all. So it’s particularly rewarding to me that people have accepted it and embraced it. I stared at that title for a good year before I was able to write it. I knew I had to say it because I was being very critical of the United States and our foreign and domestic policies, but I was being very critical of the country from a point of view of a patriot—as opposed to just doing it to get attention, or doing it just to be a contrarian or whatever. I wanted to make sure I was making it very clear that my criticism was coming from a patriotic point of view, and the country is bigger than individual political parties. For 30-40 years now, I’ve been talking about how they’re football teams, and all that matters to them is that their football team wins. But no matter which football team wins, the American people lose.

Beyond “Little Steven’s Underground Garage,” you also created the Outlaw Country format on SiriusXM. How did that come about?

I don’t have much interest in the modern world, and I don’t pretend to. I live in my own world. Many years ago, I was asked by a mutual friend associated with Billy Ray Cyrus if I could help him out and maybe write something with him, or for him. So I tuned in to country radio for a minute, and I started asking my country friends: “Whatever happened to Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Hank Williams? What about those guys?” And they said, “They’re completely out of fashion now.” So I thought, “Maybe it’s time for a new format.”

So, as I researched it further, I decided it would be all three generations of Hank Williams— all the traditional guys and all of the alt-country people coming from the rock world that have no place to go. So, when Sirius Satellite came along, a friend of mine became an advisor there and asked me for some suggestions. That’s what led to it becoming a format.

You also directed and produced “Eddie Brigati: After The Rascals,” which debuted in April. What led to that?

I was called in to reunite The Rascals in the early ‘80s, and that eventually led to me writing and producing the Broadway show Once Upon a Dream [after it premiered at Port Chester, N.Y.’s Capitol Theatre], and then it ran around the country. About 100,000 people saw it, but three out of four of The Rascals started to become flaky, while Eddie Brigati—the guy they had blamed for breaking up The Rascals and was supposed to be the problem guy—turned out the exact opposite.

So when that ended so unceremoniously—and tragically, because it was the best work I had ever done— I said, “I want to do something with Eddie and have him be able to work without the other Rascals.” It’s more of a cabaret act; we’re bringing Broadway songs into it, and he does different interpretations of Rascals songs. Eventually, I’d like it to go to Vegas and, hopefully, everywhere else. I’ve got a lot of problems, but thinking small isn’t one of them.