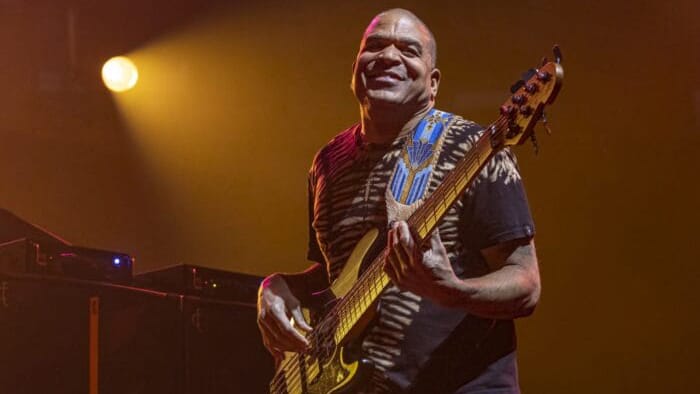

Oteil Burbridge: The Same Ethos If Not The Same History

photo: Bill Kelly

***

On September 23, 2018, Oteil Burbridge brought a version of his solo group to the Borderland Festival in East Aurora, NY. The bassist’s band for this appearance included guitarists John Kadlecik and Scott Metzger, drummer John Kimock and Oteil’s older brother Kofi on keyboards and flute. The five musicians delivered a set of Jerry Garcia/Grateful Dead-themed material that was memorable in the moment and carried additional resonance because Kofi Burbridge passed away five months later.

The Oteil & Friends performance has just been released as a limited edition two-LP set. This was not just the final time that the Burbridge brothers performed together, it also was only the second occasion in which Kofi explored the Garcia catalog with Oteil (with the previous instance occurring one day earlier on Kofi’s 57th birthday at the Santa Cruz Mountain Sol Festival in Felton, California).

The Live From Borderland Festival announcement came in the middle of a stacked summer for the bass player. On June 21, Burbridge took the stage at the Telluride Bluegrass Festival with the Toy Factory Project—a long-gestating, all-star collective helmed by former Marshall Tucker Band drummer Paul T. Riddle to honor the group’s catalog, that also features Marcus King, Charlie Starr, Josh Shilling and Billy Contreras. Telluride titans Sam Bush and Béla Fleck joined the action-packed debut as well.

This Sunday, July 6, Oteil will perform at Red Rocks with the Colorado Symphony to celebrate the music of Jerry Garcia. This follows two nights with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in early June.

On August 1-3, Burbridge will appear with the mighty Dead & Company for three highly anticipated shows in Golden Gate Park.

Beyond all of this, his recent and ongoing endeavors include gigs with fellow Allman Brothers Band alums as The Brothers, performances with Grahame Lesh, an Oteil & Friends tour and other tantalizing creative explorations.

Moments before speaking about these projects, Burbridge received a special delivery. His new Dire Wolf bass had arrived. Inspired by Jerry Garcia’s Wolf guitar, it utilizes the same wood and electronics with the goal of replicating that instrument as much as feasible in the bass format. Asher Guitars realized Oteil’s vision, which was certified by original luthier Doug Irwin and facilitated by the Grateful Guitars Foundation (which accompanied this gift with a $5000 donation to Can’d Aid in support of music and arts education). Oteil will bring the new bass out to Red Rocks for the Jerry Garcia Symphonic Celebration and then it’s on to Golden Gate for an experience that he pledges will be equally stirring and surreal.

**

The release of Live From Borderland was prompted by your brother’s participation in that show. As I understand it, he also played a role in the Toy Factory Project by introducing you to the music of the Marshall Tucker Band back in the day.

The first time I ever heard of them was through Kofi. We grew up in Washington, DC, then Kofi left home at 14 years old and went to the North Carolina School of the Arts because he was a child prodigy. When he was down there in North Carolina, that’s where he was exposed to their music.

He might have first heard about them at the Potomac School where we went but it wasn’t on my radar. I know for sure that after he was down in North Carolina, I remember hearing about Marshall Tucker Band for the first time, along with Mother’s Finest—Wyzard was one of my really big heroes and is a friend now. Then I heard the Dixie Dregs on Midnight Special and went and bought their record because to me it was like Southern fusion. It’s like classical rock from the south. That was also the first time Capricorn Records got on my radar.

I wouldn’t have guessed that Kofi was an MTB fan.

Well, Kofi was into all music. He loved sounds and patterns and all different styles. I never heard him really dog out anything. There’s plenty of stuff he didn’t buy, but I never heard him say, “Oh God, that’s awful.” He would just move on to something different. He was discerning but not judgmental.

But I understand what you’re saying. You thought it wouldn’t be his style. That was the same for me. I wasn’t into rock-and-roll at all. I had one rock record and that was Axis: Bold as Love.

I liked distorted guitar, but I eventually came to realize that for me, that really meant the blues, which is the grandfather of rock-and-roll. My favorite screaming guitarists are Hubert Sumlin, the three Kings and Albert Collins. But I have a great appreciation for rock now because I can see the connection. All these guys—the Allman Brothers, Marshall Tucker Band and a lot of the other southern rock bands that I’ve never really listened to like Skynyrd—they all had a deep appreciation for the blues. So did the old school country artists.

Since you just mentioned Hubert Sumlin, can we pause and talk about him for a moment? While plenty of music fans are familiar with Albert, B.B. and Freddie King, as well as Albert Collins, I sometimes wonder if Hubert gets his due these days. What are your thoughts?

Well, here’s how that works, and I see this now that I’m older. It was never about his due. He got screwed so bad in so many ways just being black in America at the time that he came up. But people are hearing Hubert through all kinds of other guitarists and don’t even know it.

For instance, here’s another similar example—there’s a young drummer out of Atlanta, who I was trying to turn onto Zig Modeliste from the Meters. I was listening to one of the records he was into and it was a hip hop record where they had sampled a bit of the Meters. I was like, “Dude, that’s Zig right there!” Then he goes, “Oh, I know that beat!” He was already playing Zig although he didn’t know it and he was playing it very well.

So Hubert gets his due through all these other musicians who are acclaimed and get their due. They know who Hubert Sumlin is and they give Hubert his due because he inspired them.

Some people are just a light and Hubert was a light that has just shone down decade after decade and continues to be passed along.

Even from me, though this interview, I’d encourage people to go listen to “I’ll Be Around” by Howlin’ Wolf. If you were to ask Keith Richards, Clapton or a lot of other iconic guitarists, they’d say, “Oh my God, that’s the most insane guitar! Hubert Sumlin is a God!”

Moving to Paul Riddle, you first met him during your initial tour with the ABB in the summer of ’97?

Yes, that’s when we must have met because I can’t imagine Paul didn’t come out. We were doing the full round of amphitheaters, so we went to North Carolina. Is Walnut Creek the one in North Carolina? I’m going by the old names.

Yes it is. And for the record, I hear you there—it’s always Great Woods and Deer Creek to me.

Exactly! [Laughs.] So when we would come through North Carolina, he’d come out and sit in. He would always jump up on Jaimoe’s kit and play something. Of course you fall in love with Paul in about 15 seconds. Then, at some point—I mean well over a decade later—we started talking about doing something together. I was like, “Man, I’d really like to play with you on your turf and do some Marshall Tucker stuff where you’re the ring general!”

He thought it would be great to have me and Kofi because he said, “My favorite thing is country funk.” So he wanted me and Kofi to put some more funk on the music. He called it the Oakland stroke. He was thinking of this band from Oakland called Cold Blood. I had heard of them, but I wasn’t really familiar with them until Paul said it. That’s when I realized how seriously funky they were.

Then Kofi passed away and the pandemic happened, along with all this other stuff. Life was just lifing us, but Paul never gave up on it. I said to him, “If you’re still up for it, I’m still up for it. We’re both still alive and we can both still make it to the stage. So if we can get it together, let’s do it.” Well he just wouldn’t turn it loose, and here we are. It’s been even better than we thought, and we had super high expectations.

You mentioned Jaimoe. As I understand it, he’s been friends with Paul for quite some time, going back to when Paul was still a 16-year old, starting out with the Marshall Tucker Band.

Jaimoe not only had a special relationship with Paul, but also with Paul’s parents. Jaimoe promised Paul’s dad that he would not let him get involved in all the rock-and-roll nonsense, and he was true to that. I think Paul was the least involved in all of that stuff out of everyone in the Allman Brothers and Marshall Tucker Band, which is why he’s doing well today. He’s not broke and he’s been teaching drums to little kids for decades and decades, passing on his beautiful spirit and his drumming knowledge. He’s been doing the give-back and waiting for this day to happen. It’s been a long time coming.

[Note: Riddle left Marshall Tucker Band in the early 80s. Before Oteil joined the Allman Brothers Band in 1997, Riddle performed some shows with the ABB, particularly during their 1994 and 1996 summer tours when Jaimoe was sidelined due to a back injury.]

In terms of the Toy Factory Project show, I imagine it was tricky to pull together given everyone’s schedules. With that in mind, do you think there will be more in the works, whether it’s a one-off or possibly even a tour?

Yeah it was super tricky to make that happen. Bobby Cudd, who’s one of the most legendary booking agents in Nashville pulled it all together. We all had the date or made the date available. Then we slipped in there like a SEAL team in the dead of night. [Laughs.]

But we’re definitely going to do some more dates. It’s too good not to keep it going. It’s just a scheduling thing. I don’t think that with all our schedules we’ll be able to do a whole tour, but honestly, I don’t really want to do that kind of thing anymore. It’s really tiring and it takes a lot out of you. I was glad when we started doing residencies with Dead & Company.

The Brothers are probably just going to do short residencies. I don’t know how many in a row Jaimoe can do, and I would rather do that anyway. Let’s just go out for the weekend, do two or three nights and come back home. It can sometimes feel like a war campaign when you do 30 dates.

But Paul’s 71, I’m 61. We’re like, “Alright, for these next 10 years, let’s do some dates. We’ll see where we’re at.” [Laughs.]

It sounds like the record that all of you made with Paul is done. Do you have a sense of when it’ll be released?

I believe it’s mixed, mastered the whole thing. But at this point I have zero idea when it’s coming out. Since we’ve been waiting so long, it’s sort of hilarious to me that we’re finally talking about this. It’ll be worth the wait for all of us, though, I promise. [Laughs.]

In terms of the personnel in the Toy Factory Project, how did everyone come together?

Paul T. Riddle is the nexus for everyone. That’s even true for the studio—Peter Frampton lent us his studio. Peter had never met Paul but he was such a huge fan of Marshall Tucker Band, and he works with Paul’s producer, Chuck Ainlay, who might be the top producer in Nashville. As I understand it, Peter got on the phone with Paul and he was so enamored with him—the way anyone would be—that he offered up the studio.

When we were sitting in there in Peter Frampton’s studio, he’s got this wall in the lounge that’s like the sickest wall of fame wall you’ve ever seen in your entire life. It’s pretty much got every rock star you can imagine, all icons. I mean it’s nothing but icon after icon after icon and they’re all really young—The Beatles, Elton John, everybody.

Of course Peter Frampton himself looks like a teenager in lots of them. I’m like, “Did he do all this by the time he was 20? Are you kidding me?” My mind was just blown standing there looking at the wall. The whole thing was like a dream and Paul’s the nexus for all of it. Good things come to that man.

Of course Paul was also quite young when he started out. Not only that but at the outset of their career, the Marshall Tucker Band released a lot of albums in a short period of time.

When I was at Paul’s house, I counted 26 gold and platinum records. I was like, “Damn dude!” [Laughs.]

I was a Grateful Dead fan long before I became familiar with the Marshall Tucker Band. I can remember noticing that MTB performed “Fire on the Mountain” and wrongly assumed it was a cover. The Toy Factory Project played those songs back-to-back in Telluride. Was that your idea?

I was the one who pitched it, but Paul told me that Marcus had already done it at one of his own gigs. I sang the one that we did but since Marcus had already done it, I felt, “Cool, we’re good.” It was a great crowd pop. Now I’ve got the Marshall Tucker “Fire on the Mountain,” totally stuck in my head and I cannot get it out. [Laughs.]

Thinking back on the set, is there something that really stands out to you from the performance?

The whole thing! People should watch it on Nugs.

I was sick as a dog, though. I got the worst altitude sickness. I don’t let my manager book me above 7,000 feet anymore. Red Rocks is the highest I can go. I don’t think I’ve done anything in a few years higher than Red Rocks but Paul was so excited about this gig that I couldn’t say no. I kept it from my manager for a little while and then he was like, “What? You’re going to Telluride? Are you serious?” I was like, “Man, if it wasn’t for Paul Riddle, there’s no way I would do it.”

I came up two days early and the first two days I was fine. Then show day around 4:00, it was like emergency room level. When it was really bad right before the show, they said, “We can give you this IV.” I was like, “Yeah, but we have a 90 minute set and I’m going to have to pee three times. I can’t shoot all that liquid in me and then go on stage.” So it ended up being the first time I ever played with tubes up my nose. I had to just gut through it. I was really bummed because it was on Nugs and I looked like I need to be in a stretcher. But I got through it and I was even able to sing “Fire on the Mountain.” So we did it. We’re carnies, man.

The first morning in Telluride is always fine for me but I’ll often wake up with a pretty brutal headache a day or two later no matter how much I hydrate.

Now I know how to do it. You need to get the IV before you even go, and then get one when you’re there—mine had extra magnesium and zinc. Make sure you have an oxygen tank in your room and not just the little canned things. I’ve also learned there’s a shot you can get—I think they shoot it in your thigh—that will oxygenate you.

Béla and Sam and those guys, they’re like the kings of the Telluride Bluegrass Festival, so they’re there every year. Béla was telling me what he and Abigail take to help them deal with the altitude. I said to him, “Well, now I know, but I’m still going to try to avoid it.” It’s an amazing event, though, and we had an incredible show.

Béla and Sam added so much to that set and really helped to underscore the range and scope of the music. At what point did you know that they were going to participate?

I don’t think I found out until show day and I was so psyched. Standing on stage with those two guys, given my history with Matt Mundy and all my other friends who play bluegrass, that was so special. They’re also the sweetest guys on earth. Béla sat next to me in the dressing room. I got in there and I was so bad that everybody cleared out. I was like, “Hey, you don’t have to leave!” [Laughs.]

But Béla just sat on the couch with me and he was just so gentle and sweet. It was like he was at my bedside in the hospital. He’s a beautiful cat and so is Sam. Of course, they played their butts off and there’s so much stuff in that music for banjo and mandolin. It was just perfect. And, man, Billy Contreras, the fiddle player—holy crap, he is something!. The whole band is just amazing.

There’s banjo on a lot of the original stuff and Charlie Daniels was doing the fiddle parts. So it’s very, very harmonious with bluegrass and country, but also funk and jazz and Latin music and everything. It’s all in there, sort of like Col. Bruce and the Brothers and the Dead. It’s everything and the base of the gumbo is country and blues. It’s really great.

It’s always fascinating for me to think about your personal path and how much of the music you’re creating today you discovered later in life. I think there’s a real value in how you came at it the way you did.

I think so too. There’s almost no other way to come at it. I was lucky in that my dad had country and bluegrass records. He also had classical Indian music, he had folk and he had blues. The only blind spot he had that I later got him with, was I turned him on to Howlin’ Wolf. He knew about Robert Johnson and Son House and all that, but that was the one blind spot. I was so psyched to be able to turn him on to something for the first time. I didn’t think it could be done. [Laughs.] So because of my dad, I grew up open to all styles. Whatever culture on this earth makes music, I want to hear what it sounds like. I probably want to eat their food too, because that’s how you really learn about people.

Then Col. Bruce gave me all those things that were outside of my preferences and really educated me by showing me what I was missing. That’s why I was ready at that point to play with the Allman Brothers or the Grateful Dead or the Marshall Tucker Band. Pre-Col. Bruce, I wouldn’t have been ready to do it.

You mentioned that the entirety of the Toy Factory Project show felt good. Having said that, was there a particular song that surprised you or knocked you on your butt?

Well, the one that I would have thought I’d be telling you we didn’t get to do because we ran out of time—those jams just got so good. But in the studio we did an amazing version of “Heard It in a Love Song,” which is mostly vocals, but we didn’t do it that night.

What I can say is that after playing the show, those songs are stuck in my head. That “Fire on the Mountain” is super stuck in my head. “Can’t You See” and their big hits? Super stuck. That’s when you realize the power of those songs. All these years later, we could stop playing any of those songs and the crowd would finish them. It’s been a long time but it makes you realize how much of an impact they had.

While that’s true, I also suspect that a number of younger people—like the folks who have started coming out to Dead & Company—might not be altogether familiar with the music. I imagine the glory of the gig to some degree is introducing a new audience to Paul and MTB.

Yeah, it’s interesting. A friend of mine teaches film at a university—shout out to Eric Limarenko, he’s a producer of my podcast. He asked his students, “How many of you have heard of the Grateful Dead?” More than three quarters raised their hands. Then he said, “How many of you have heard of the Allman Brothers Band?” It was only a third of them. I was like, “We have to change that.” I want to make sure that’s not the case for Marshall Tucker Band as well.

Let’s talk about the new vinyl, which presents your final performance with Kofi at the Borderland Festival in 2018. When we were discussing A Lovely View of Heaven you told me about the show and mentioned his incredible flute solo during “High Time,” which appears on the record. How did this double album come to be released?

First off, thanks to Phil Harris who recorded it, although we certainly didn’t know it was going to be my last gig with Kofi. I think someone heard about it and was like, “Hey, that was Kofi and Oteil’s last gig together. Is it on tape anywhere?” I don’t remember whose idea it was to put it out on vinyl—maybe my manager, Ben Baruch—but I remember getting the email from Ben telling me, “They want to put Borderland out on vinyl.” I was like, “Wow, that’s cool. Especially now that I have a turntable again, I’d love to listen to that.”

That “High Time” flute solo is on there and it’s so good. I remember people were just screaming after Kofi ripped that beautiful solo. The whole thing is worth it just for the solo alone.

You just never know when your last gig is going to be with a person. You can’t know when you’re doing it. Then you look back and you’re like, “Damn, if I had any idea that was going to be the last time, it would’ve blown my mind.” I was in bed last night listening to it and just grooving. I had to remember to be kind of quiet. [Laughs.] I hadn’t heard it in a while and I was just reflecting on that night, and the night before as well—getting to spend his birthday with him.

I don’t think Kofi had previously played a full set of Grateful Dead and Jerry Band music. That’s really special too, because at least he did it before he left us and now we’ve got it on vinyl.

Do you recall how much rehearsal you had for either of those gigs?

There wasn’t any. I think I sent the song list around but I didn’t have the set written out with what order the songs were going to be. I just had which songs I wanted to make the set from. In that situation, everybody pretty much knew the songs except for Kofi, who had perfect pitch. He had a five hour drive to the gig and he’d listen to the tape on the way. Then by the time he got there, he knew the whole gig. I was like, “Damn, dude!” [Laughs.] But when you’re a Jedi, you’re a Jedi. So I knew he could do it. We literally were going through a couple things in the dressing room—just form endings and segues.

In looking at the two shows, while there are a couple songs in common, the setlists are not the same. You played the gig in Santa Cruz on Kofi’s birthday then flew across the country to appear at the Borderland Festival in New York the next day. There are plenty of folks who would just repeat the setlist for convenience’s sake. To your credit, that’s not the sort of thing you’d consider.

If I’m going to do a set of mostly Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia Band stuff, I’m definitely not going to do the exact same set. We didn’t even do original songs, other than a John Kadlecik tune [“What’s Become of Mary”]. We definitely were going to mix it up.

I still think it’s something you take for granted that’s second nature to you. Of course, maybe it’s just how you approach life more broadly.

Exactly. It’s a philosophy of living. I think that’s why even though I didn’t grow up with that music and it wasn’t in my background, the philosophy was in my background. Plus, the musical philosophy of being open to all these different styles of music was definitely in my background. We had the same ethos, I just didn’t have the same history. But it all works together today.

Is there a song that really struck you when you were listening back the other night?

I’ve always liked when he’s playing flute. That’s also something I never hear in Dead music. So when Kofi picked up the flute, it’s like, “Oh man, here we go!” It’s great to hear the crowd respond to that because they’re not used to it either. Of course Kofi was always really great at whatever. He’d just put that Kofi thing on it.

I’m really glad that we got to do that because I’m never going to get to do it again. I think everybody’s probably going to like a different one the best because it was just that kind of night. He killed it, man.

On Sunday you’ll appear at Red Rocks with the Colorado Symphony. A few weeks ago you performed two nights with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. What were your goals or expectations going into those performances?

Well, I don’t have expectations. I’ve said this a lot recently that expectations are premeditated resentment. I heard that from a TV preacher and I was like, “That is some serious truth right there.”

Was there a song you really wanted to hear in that context with the BSO?

Well, I’d always wanted to do the long “Terrapin”—the whole thing, because it’s all orchestrated on the record. I think Bob just did it at Royal Albert Hall

All the charts are there and they’re beautiful, with the violin parts. Different people did the arrangements, but everybody did such a good job. Getting to sing “Morning Dew” with the Boston Symphony behind me, oh my God! I was just like, “Don’t get choked up, man! Look forward, go forward!” It was so emotional.

I know it’s going to be the same way in Colorado.

What were the greatest challenges for you in that setting? I’ve heard from other people who have performed with symphonies that decibel levels are very important to classical musicians, who are protected contractually from things getting too loud for fear of damaging their hearing.

Yes, that’s a real thing. You’re made aware of it in advance but that wasn’t an issue for me. I’m not trying to blow out anybody. I’m a jazz guy. I can play where the drums are not miked and just play to the bass drum. That’s plenty loud.

At Symphony Hall, I was on inner ear monitors and that’s how it is with Dead & Company. So my amp can be all the way off. It’s all the way off with Dead & Company, so I’m used to that already. It’s getting to turn it on that throws me. [Laughs.]

I would imagine I’m going to be able to turn my amp up at Red Rocks more than at Symphony Hall. It was pretty much all the way off, and then I think the second night they were like, “Hey man, we could really use some more bass, you can turn it up if you want to.” So I did. [Laughs.]

It was a big thing for Tom [Hamilton]. He was like, “I need more bass, dude.” He’s used to having my real bass with JRAD.

What did the orchestra sound like from your vantage point?

I had to be careful because if I get too much of the orchestra, it drowns everything out. That would be a problem because you can’t get one bar off with an orchestra. It’s the exact opposite of the Grateful Dead. There you have jam parts where the part is however long we want it to be, but as soon as the orchestra is involved it’s down to the bar.

So if I can’t hear the time well enough, I’ll get off and I can’t afford to be off, not even one beat of one bar. It happened to me the first night doing “Morning Dew.” Thankfully the next night we played that again and I was able to really do it properly. That’s why mistakes are the greatest teachers because you may make a different mistake, but you’re not going to make that one you did the night before because it kept you up all night.

So I couldn’t put too much of the orchestra in my ears, but then when I heard it afterwards, I was like, “Wow, man! Wow!”

Do you know if anyone in the orchestra was a Deadhead?

I didn’t speak with any of them about that, so I don’t know. I imagine they have different tastes across the board like all of us, but they can appreciate good musicianship. My friends were laughing because they said they could see some people in the orchestra who weren’t really into it at first, but then they got into it after a while because regardless of style, you can appreciate if someone has mastered their instrument and you can also appreciate someone’s intention.

Well, there’s a lot of joy up there. It’s pretty infectious. You’d need a very large stick up your ass to resist all that joy. I mean if you put me and Melvin together and we don’t get you, you need to pick out a casket. [Laughs.] I’m sorry, I’m not bragging, I’m just saying, “Come on, man!”

Last November you returned to Floki Studios in Iceland to work on another album. What is the state of that project?

It’s recorded. I think we have some keyboard parts to finish and then we can finish the mixing. We’ve done preliminary mixing, but it’s been quite a busy year. I want to get it out for the sake of the label, but there are so many things going on, between Dead & Co., the Brothers, Oteil & Friends and the Toy Factory Project. I’m also doing all this stuff with Grahame Lesh. Of course, there are all these other things as well, with my seven and 10 year olds.

But I think we’re about to start getting back to the mixing because Soulive just went out there and also did a record in Iceland. Al [Evans] the drummer was producing our record there.

As you referenced, this has been quite a busy stretch for you. We didn’t touch on everything you’ve done over the past few months and I know there’s more to come.

The Unbroken Chain stuff at the Cap Theater was so moving, man. I got to spend time with Phil before he passed when I went out there to do the Darkstarathon. So doing that at the Cap Theater really meant something special.

They’re also talking about some Q gigs. I’ve never played this music with Jimmy Herring, which is insane. A long time ago, when he first got the gig with Phil & Friends, I remember him telling me, “You would love ‘King Solomon’s Marbles.’ I would love to play that tune with you.” It was “King Solomon’s Marbles” and “Unbroken Chain” in particular. He thought that I would really love those tunes, and he was exactly right. So thank you, Mr. Herring. He called that many, many years ago.

People would be disappointed if I let you go without asking you to share your thoughts on the upcoming Dead & Company shows in Golden Gate.

It’s so crazy because Bill Kreutzmann flew us out to Grateful Dead 50. Me and my wife were standing there looking out at the stadium crowd and I asked her, “Can you imagine this being our life?” She said, “No, I honestly can’t.” Then I was like, “Me neither. This is next level.”

Well here we are 10 years later. Nigel’s 10 years old, and we’re rolling into Golden Gate Park for three days to celebrate 60 years of the Grateful Dead. It’s very surreal, man. Very, very surreal. And I’m going to be playing it with this Dire Wolf bass. Oh my God!

I heard someone say that they were going to cap the audience at 60,000. Then the next day my Instagram feed showed a picture of the Dead playing there with 300,000 people. I was like, “I hope you’re planning on sealing all the manholes, because I don’t think you’re going to be able to cap this thing. People are going to be burying supplies in the park!” [Laughs.]

It’s going to be a lot, but it’s going to be so cool. I’m psyched that Sturgill, Billy Strings and Trey will also be playing. It’s going to be so great! I mean, come on!