moe.: The Land of Guts and Glory

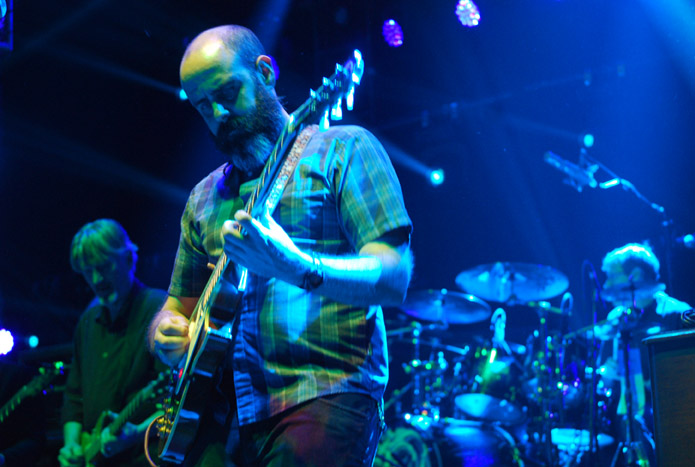

Photo: Jay Blakesberg

“I honestly don’t have a great grasp on why any records sell or don’t sell,” moe. bassist Rob Derhak admits. A founding member of the group, which is approaching its 25th anniversary, and one of the band’s three principal singers and songwriters—along with guitarists Al Schnier and Chuck Garvey— Derhak is quietly celebrating the success of moe.’s most recent album, No Guts, No Glory (Sugar Hill). Since its release this past spring, the record has garnered good reviews in the music press, even better ones from the group’s hardcore fan base and is well on its way to becoming one of their best-selling discs ever. This in an era when nearly every artist laments, “Nobody buys albums any more.”

“Maybe this one’s doing well because our fan base has expanded. Maybe it’s because the record company is doing something right. Maybe it’s because the album’s good. I don’t know,” he laughs. “Maybe we had no competition that week.”

Derhak is enjoying a relaxing day between tours, hanging out on the back porch of his rural Maine home, which looks out on the peaceful scene that partly inspired his lilting song “The Pines and the Apple Tree” on No Guts, No Glory.

“We still like recording,” he adds. “We still want to put out albums because we were kids in the ‘70s and the early ‘80s, and we were all into getting that new album from the bands we loved. Even if albums aren’t as big of a deal as they were when we were kids, it’s one of the ways we make our art. It’s also sometimes fun to make something with somebody else—to have them produce and to get their input. That was definitely the case with this one.”

On No Guts, No Glory, that “somebody” was producer/engineer/ mixer Dave Aron, who is best known for the many hip-hop projects he’s worked on with Snoop Dogg. Aron’s résumé also includes work with R. Kelly, Sublime, Lil’ Kim, Prince and Tupac—not exactly a cavalcade of jamband stars, to say the least. But here’s the thing: He’s been a serious moe. fan and friend of the band for many years, and his jamband bona fides also include going to dozens of Grateful Dead shows back in the day, so he definitely “gets” the jam aesthetic and also what makes moe. so unique and engrossing.

“I’ve known these guys for 15 years now,” Aron says from his LA studio, Hollywood Way. “I met them in 1999. Banyan—Stephen Perkins’ band, who were friends of mine—was opening up for moe. at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York, and I was playing [clarinet] with them. So I saw them that night and I’ve seen them a bunch of times since, too. I love those guys, and we’ve been waiting for an opportunity to get in the studio. And actually, about 10 years ago, I got them to come to my house, and we jammed and made an impromptu track up there. But I’m not sure they felt it fit on their album or what they were trying to do at that point. There was one section they did where I said it would make a great rap loop, so I actually made a rap beat out of it and gave it to Kurupt Tha Kingpin to rap over, and we made a little song for his mixtape out of that. But this album was the first time we worked together seriously in the studio.”

Truth be told, if moe.’s original concept for the album had come to pass, then Aron would not have been involved. The group had made their previous album, 2012’s What Happened to the La Las, with a producer, John Travis, and though the band members liked him personally and appreciated his viewpoint and his ability to act as a musical mediator, they hoped to go in a different direction this time around.

“I think with that album, we sort of peaked out with having a producer who was really into the arrangement of songs and trying to bring his own take on what we do,” Derhak offers. “So when we decided to make a new album and we had our usual brainstorming sessions that are part of our process, we came up with the idea of doing something really different. Part of it was wanting to get away from what we’d just done, and the biggest thing we could think of was: ‘Let’s make an all-acoustic album.’ Or if not all acoustic, at least immersed in acoustic instruments, with maybe some tasteful electric guitar and maybe a Hammond on there.

“So it started like that, and then we thought, ‘How can we embrace those cool, ‘70s Eagles or acoustic-y Zeppelin things?’ So we said, ‘Let’s go back and record the whole thing on two-inch tape and make it all analog like we did when we first started recording. We’ll do that, and we’ll go to Levon Helm’s barn because how cool would that be?’”

However, that’s not quite what transpired. The band lined up multi-instrumentalist and longtime Helm associate Larry Campbell to produce the album at The Band drummer’s studio, only to see these plans gradually fall apart. First, they learned that Helm’s barn would not be available throughout the recording period they had targeted. Then, Campbell informed the group that he would be away for portions of the recording process.

“Basically, our great plan completely fell apart,” Derhak recalls. “It was like a comedy of errors. So then, we were left with, ‘Well, now what do we want to do?’ Well, we still want to stick with our time frame, and we’d always talked about doing something with Dave, so we just called him up.

“We were originally supposed to go to LA to his studio,” he continues, “but for personal reasons, for some of the guys in the band, they couldn’t be that far away from home, so Dave agreed to come out to Connecticut. But right before we were scheduled to start recording, I think it was Al who said, ‘You know what? I’m not really feeling this acoustic thing.’”

Aron adds, “When they came to me and said they maybe wanted to do this acoustic album, I said, ‘I’m sure it will come out great and be really cool. But for our first project together—I’m so good with drums and bass, and getting live instruments down is my thing—for us not to go that route, it seems like…huh?’ What I said to them is: ‘I want to make the most moe. album we can possibly make.’ I wanted to capture the essence of what they do live and what people really love about them. I didn’t want to experiment with something. I didn’t think doing the acoustic album would be using me to the fullest potential, and they seemed to agree with that.”

Derhak completes the story: “So after all this planning and going through all this, maybe five days before we started recording, we said, ‘Let’s go in and record our stuff and do it electric and make it as big and cool as we can.’ And that’s what happened. It was the typical moe. thing where no matter how we try to do something else, we end up still doing it the moe. way.”

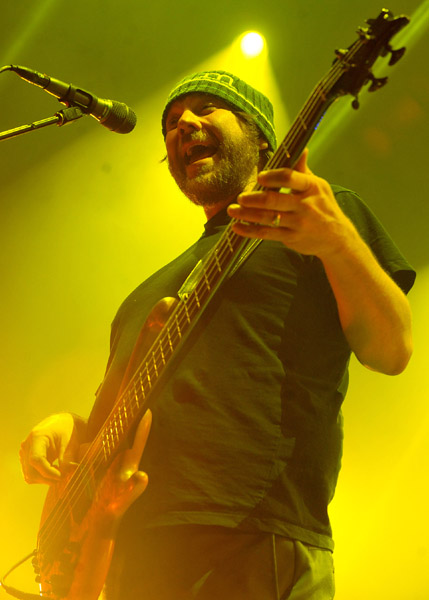

Photo: Stuart Levine

There is still a prominent acoustic thread going through much of the album, but moving from the mostly acoustic orientation to good ol’ moe. allowed the band to bring in a few songs that probably would not have fit the original approach, including Schnier’s lusciously psychedelic, Pink Floydian “Silver Sun,” and Derhak’s complex nine-and-a-half minute “Billy Goat,” which he says he wrote about his father after he died three years ago. The latter is quintessential moe. with its deft and dizzying blend of prog-rhythmic changes, tough rock riffing, bright harmonies and a circuitous middle jam that builds to several fiery climaxes, as Schnier and Garvey duel and also spit out unison lines, shift tempos numerous times and still magically arrive at a pretty, melodic vocal coda.

Surprisingly, though, the most raging and intense rocker on the album, Garvey’s “Annihilation Blues,” which kicks off No Guts, No Glory with a hard-rock flash, started life as an acoustic guitar-and- voice demo.

“It was a grim country-blues song,” Garvey says by phone during one of his days off. He’s out doing errands with his wife about an hour outside of Cincinnati, where he’s lived for the past 16 years. “It was actually one of the few songs where everyone in the band said, ‘You know, that’s pretty good as is,’ but then we did change the arrangement a bit. It got pretty…electric,” he says while chuckling. “It has this pulse that builds to this sinister pile-driving thing at the end—it’s really fun to play live.”

When it came time to record those tunes and the other eight that make up No Guts, No Glory, the band and Aron convened at Carriage House Studios in Stamford, Conn., and cut the album essentially live with all five musicians playing at once, then added various textural overdubs later. In addition to Derhak, Schnier and Garvey, the group includes their powerhouse, turns-on-a-dime dummer Vinnie Amico and percussionist Jim Loughlin, who, these days, concentrates heavily on mallet instruments—vibraphone, marimba and xylophone, which are interesting tonal colors for moe.’s sound.

“Those instruments sort of fill the spot where moe. always had an empty place to fill, like a keyboardist would,” Derhak says. “It’s nice to have parts that stand out and are a little different, as opposed to other jambands that would have a Rhodes or a Hammond or some other keyboard there.”

As Garvey explains, “We wanted this album to feel like a band playing. We tried to track everything with all of us playing together, and that’s actually a really big part of why the album sounds the way it does. Dave wasn’t totally convinced about everyone playing live all the time, but he was adamant that we not get too clinical about what we were doing. He had seen us a bunch of times and really knew what the band was about and what our live audience is about, so he was saying, ‘Keep it raw, maybe leave some of the mistakes in. As long as the energy is good and it speaks well, that’s what you need.’ There’s always this desire to fix things in the studio because you have the ability to do it technically, but it’s not always necessarily the right move. A lot of people still operate in that fashion, but we don’t get down to that microscopic level and stitch everything together in a non-organic way. Sometimes it can sound good when you do that, but you can also realize the thrill is gone.”

While most people likely won’t hear any mistakes on No Guts, No Glory, Garvey reveals that he does. “There’s intention, and there’s the final product, and you know what your intent was. But if you’re not part of the process of actually trying to create it, you don’t have any preconceived notions of what it should sound like. All you get is the end result. I’ve heard, through the years, that there are weird things all over Beatles recordings—out of tune vocals and this and that mistake. That’s hardly a good comparison—to say moe. and The Beatles. The mistakes of the two bands are not equally charming,” he laughs. “But in both cases, at least you can tell that real people are playing it and singing it—there is a life to it and it really doesn’t matter that it’s not ‘perfect.’”

From Aron’s perspective, “everything fell together perfectly. I did what I usually do. I don’t try to guide a project too much in a direction I feel is going to be right. I let it unfold into what it is. Like with Chuck and Al’s guitars— those guys have been playing so long together, they know how to make it work and when to come in and out. I’m not stepping in to change that up. I figured they’re going to stay out of each other’s way or complement each other where they need to, and then, if there’s a problem, I’m going to say, ‘Do you think these two guitar parts work together, or should you maybe go in two different places?’ But they usually have it down. This album was really a whole group effort. I was there to guide it and make it musically proper so everything fits together, but I didn’t want to impose on them too much and get them off-track from what they do so well naturally.”

The result of the months recording at Carriage House and Aron’s subsequent mixing sessions at his Hollywood Way facility, No Guts, No Glory stands with the best of moe.’s 10 other studio efforts, including Tin Cans and Car Tires (1998), Wormwood (2003) and Sticks And Stones (2008). Several of these songs are destined to become fan favorites for years to come. Besides the aforementioned three, there’s Derhak’s catchy “Blond Hair and Blue Eyes” (which includes what Aron calls “a Van Morrison-style horn part,” featuring trumpet, trombone and himself on clarinet); the Chili Peppers-ish “Calyphornya;” and Schnier’s wonderful “Little Miss Cup Half Empty,” which sounds like a meld of early Elvis Costello, chunky, rock guitar riffs and country-reggae. In other words, the album is typically eclectic and impossible-to-pigeonhole moe. This band has always kept its fans off-balance and guessing. It’s part of the group’s collective DNA.

It’s also a major reason why their fans keep coming back year after year. These are good days for moe. The venerable Northeast jamband is enjoying one of their best years ever. Touring workhorses even in their leanest times, they’ve really outdone themselves in 2014, hitting Europe twice and Japan for a single festival gig in mid- summer, in addition to their usual bounty of U.S. club, brewery, theater and festival dates. (This year, the list has already included Wanee, Summer Camp, the Great South Bay Music Festival and Gathering of the Vibes in Connecticut, with more to come in the late summer and fall, such as the 15th edition of their own moe.down fest in Upstate New York and Railroad Earth’s ever-growing Hangtown Halloween Ball in California’s Gold Country.)

Photo: Dean Budnick

The quintet is still actively courting new supporters all over the globe. And the group relishes the challenge of conquering new territories and moe. virgins. “Going to Europe this year was like going back to our roots,” Derhak says. “We cruised around in a Sprinter van, which is sort of like an airport shuttle, and we played to small crowds—I think we played to like 75 people at one place, up to about 500 people, which is like our bar crowd [in the U.S.]. But it was really fun.”

Unfortunately, the new album has not had any formal European distribution, yet everywhere they went, they encountered folks with some familiarity of the band.

“I guess there are people who know us through the Internet,” Derhak continues, “and there are people who have traveled to see us and brought the music back to their friends. Playing at Jam in the Dam [in Holland] probably helped, and there are a lot of people who have come to the U.S. and seen us at festivals. A lot of them seem to be older people who were flower people, so they’re older than us and were probably into the Grateful Dead or some European prog-rock scene. The Allmans are still big with a lot of people over there. We’re sort of on some of those people’s periphery. It’s a very old-school, word-of-mouth kind of thing.”

Germany, especially, seems poised to grow into a moe. stronghold. “The crowds there have reacted really well,” Garvey says, “so the last tour and in the near future, we’re going to be concentrating on Germany. It’s so big—and there are so many people there— that if something substantial grows, maybe it can be a home base from which it can spread in other directions.”

That’s not to suggest that the guys in moe. spend every waking minute plotting world domination. As a quirky and idiosyncratic mid-level touring band in America, they still have a long way to go before they are a household name here, too.

“Basically, anyone who’s going to give us a good festival slot—we’ll take it,” Derhak says. “When you play festivals, you’re always playing for a decent number of people who have never seen you before—unless it’s your own festival. So at moe.down, I’d say there are a huge number of people who have seen us before. But we just played at Pete Seeger’s festival [Clearwater’s Great Hudson River Revival] and I’d say probably 75 percent of the people there were a new crowd for us because it was a lot of elderly folk music fans. We were booked as an acoustic band for that one and it seemed to go over pretty well. But when we go play Gathering of the Vibes, there’s always going to be those people who say: ‘You know, I’ve been meaning to check them out.’ But there, they are seeing a lot of bands, instead of us playing at a club, which is for fewer people but most of them are there specifically for our music.”

This contrasts with moe.down, the group’s annual Labor Day weekend festival at the scenic Snow Ridge Ski Resort in Turin, N.Y. This year’s three-day event—a 15th anniversary celebration—boasts a typically cool and varied lineup, including O.A.R., Rich Robinson Band, Lotus, Soulive, Les Claypool’s Duo de Twang and, of course, heaping helpings of moe.

“It’s been different every year, and the lineup changes a little bit how the audience is, which is interesting,” Garvey says. “Some years, we’ve wanted to have a very jamband-centric festival, so the core jam scene people will be there, and other years, we’ve had some rap stuff or other kinds of bands. We were lucky enough to get The Black Keys one year. We’ve had the Presidents of the United States, Cracker, Flaming Lips and also bluegrass people— we had Del McCoury; we’ve had David Grisman. I think there are a lot of people who go every year, regardless of who’s playing, because they know it’s always going to be really good. The whole process of doing it has been fun for us—trying to curate our wish list of bands we want to come there. Hopefully, always mixing it up like this keeps everybody interested as much as it keeps us interested.”

Derhak adds, “It’s become more of a family event as we’ve gotten older and had kids of our own. Some of our kids are in high school and some of us still have littler kids, so the backstage ends up looking more like a family picnic than a rock show, which is basically what it was at the beginning. The first few years were debauchery and crazy rock ‘n’ roll. Now, it’s like a family get- together where you see everyone’s cousins together and everyone is sitting around drinking a beer. There are definitely still parts of the camping area that are the kids who want to party. And some of the older folks rent RVs and stay in the RV section and want to be more comfortable.

“There are a lot of fans I’ve been seeing forever, and I know them personally. They have their own thing and they’re not super impressed by me. They’re not starstruck in any way. They just love the music. And I try to be accessible. But, I’ve also had situations where I’ve been accessible, and it’s around way too many fucked-up people, and they just assume I’m as fucked-up as they are, and it becomes uncomfortable. But that’s not stopping me from going out in the crowd and talking to people. I like to take my sons with me, and my daughter sometimes. At moe.down, we’ll drive around in a golf cart and go through the camping areas and talk to people.”

“We’re so lucky to have the fans we have,” Garvey concludes. “We know that we’re very fortunate to do what we do, and we’ve always tried to remain humble about it and tried to enjoy it, and not look at it as too much of a job or a too insane or surrealist way to go through life. It’s been really fulfilling to be able to do this as a job and be able to have the experiences we’ve had—the good experiences and the really bad ones. We’re never going to be Jay-Z-type super- stars, by any stretch of the imagination, and that’s fine. I don’t think I’d be as happy in my life if I had to have a security team around me at all times—even when I’m shopping for shoes.”