Mick Fleetwood: And The Band Played On

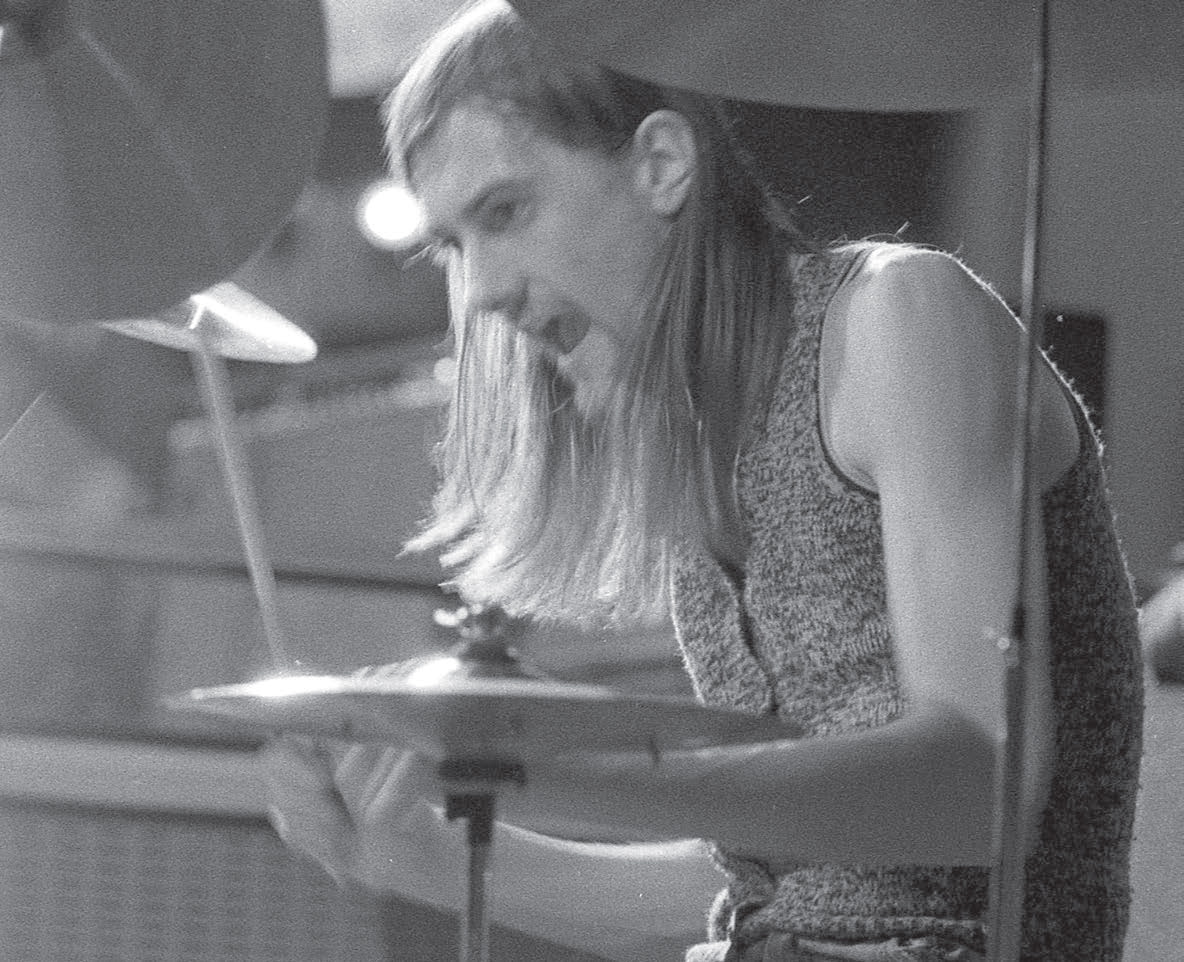

Mick Fleetwood during the Peter Green era of Fleetwood Mac (photo credit: Barry Plumber)

As he celebrates the life and legacy of Fleetwood Mac’s original driving force, Peter Green, Mick Fleetwood looks back on his band’s blues-based origins.

“Fleetwood Mac is a very odd story of survival,” drummer Mick Fleetwood says, as he thinks back on his decision to stage a big name, multigenerational tribute to his band’s original guiding light, Peter Green, this past February. “It’s probably almost fairly unique, with all the components and relationships and ladies and men and the whole caboodle.”

It’s a gorgeous October day, and the drummer is calling from his home in Maui, Hawaii. While he remains acutely aware of the global pandemic that has crippled the live-music world around him, Fleetwood is trying to stay as optimistic as possible— while still hunkering down as he prepares for COVID-19’s seemingly inevitable second wave in the U.S. But he does have some things to celebrate: He’s recently reconnected with singer/guitarist Lindsey Buckingham, who was pushed out of the band in 2018; he’s gearing up to release his recent tribute show as Mick Fleetwood & Friends—Celebrate the Music of Peter Green and the Early Years of Fleetwood Mac, and his group’s 1977 soulful slow-jam “Dreams” has returned to the charts, thanks to TikTok.

And, during the past 15 years, Fleetwood Mac have also emerged as unlikely indie-rock forefathers.

“The first time I heard ‘Dreams,’ in my mom’s car as a child, I remember thinking, ‘What is this music? I want to hear more of it,’” says The National drummer Bryan Devendorf, who released his own take on the song, recorded years ago, under the moniker Royal Green this past summer. “It was such a bolt out of the blue. Suddenly, the drums were noticeably louder, and you could feel the bass. And that voice—I was so enchanted with it.”

While most fans associate Fleetwood Mac with their stadium-sized, folk and pop-rock-leaning Rumours-era lineup— Fleetwood, Buckingham, singer Stevie Nicks, singer/keyboardist Christine McVie and bassist John McVie—the ensemble actually grew out of the blues world and have always retained a bit of their original improvisational spirit.

Before striking out on their own, Green, Fleetwood and John McVie had all performed with guitarist John Mayall in his seminal Bluesbreakers—the same group that helped launch Eric Clapton’s career. Using some recording time Mayall gifted him, Green laid down a few songs with Fleetwood and McVie, including the instrumental “Fleetwood Mac,” which he named after his rhythm section. He eventually decided to split off from Mayall and form his own project, calling it Fleetwood Mac in hopes of persuading the drummer and bassist to join him. The move worked—Fleetwood committed right away and, though he decided to stick with the Bluesbreakers for a bit, McVie signed on soon after. (Bassist Bob Brunning played on their first single, making Fleetwood the only truly consistent member of the band’s lineup.)

The original Fleetwood Mac, which ncluded second guitarist Jeremy Spencer, was an instrumental force that has long left its mark on the early improvisational[1]rock scene. Santana covered Green’s “Black Magic Woman,” members of the group jammed with representatives the Grateful Dead and Allman Brothers during a famed 1970 summit, and Green’s guitar work inspired a legion of young musicians across the pond.

“I was aware of Fleetwood Mac from the first record,” says Heartbreakers guitarist Mike Campbell, who joined the group after Buckingham’s departure a few years ago. “My first band with Tom [Petty] particularly loved the Kiln House album. ‘Tell Me All the Things You Do’ was a favorite.”

Fleetwood had considered staging a Green tribute show for years, but he admits that the plans kept getting pushed off due to his busy schedule. However, he did tip his hat to the original Mac lineup on the group’s 2018-2019 world tour, which included a number of early favorites that had been out of rotation for decades. “I was also glad they wanted to do ‘Oh Well’ on our tour,” Campbell adds of the stretched-out tune. “It’s a great guitar song and I got to ‘play out’ on it. It was also a pleasure to sing it with them.”

When Fleetwood was able to put the show together at the London Palladium on Feb. 25, 2020, an all-star mix of musicians rallied behind the cause, including Spencer, Mayall, Christine McVie, Neil Finn, Noel Gallagher, Billy Gibbons, David Gilmour, Kirk Hammett, Zak Starkey, Pete Townshend, Steven Tyler, Bill Wyman, Jonny Lang and Andy Fairweather Low, among others. The night turned out to be an unexpected final hurrah for numerous reasons, taking place right before the pandemic paused the music industry and a few months before Green’s sudden passing.

“The lovely part is that Fleetwood Mac still survives today and is really quite present in many ways, with people loving and hearing our music,” Fleetwood says. “But the beginnings of it were also eclipsed and, to some real extent, quietly forgotten. And I was driven—selfishly for me and also because of my regard for Peter and the beginnings of Fleetwood Mac—to do something of this nature.”

You staged your Peter Green celebration in February, unaware that he was going to pass away a few months later. What initially inspired you to pay tribute to Peter’s music, and the early years of Fleetwood Mac, at this point in your career?

The desire to do it was pretty simple. As the years crept by and Fleetwood Mac became more enormous—which is great, we’re all blessed—the divide from where we started became even greater. People, especially in America, don’t really know a hell of a lot about early Fleetwood Mac. In Europe and Australia, they do, but it was so long ago that it’s almost a separate part of history, so it’s nice to remind them. The music was important, and people will sometimes go to me and John—but probably more so me—and say, “Well, you started the band.” And I’ll go, “That’s not true—Peter did.” So it’s really giving kudos to the history of the band—before the beginning. It’s all about taking a musical hat off. None of this would have happened if there hadn’t initially been four crazy, young English chaps, with Peter in the driver’s seat, creating all that lovely music.

Peter was a gunslinger guitar player; he could’ve fallen into that Jimmy Page-Eric Clapton league. But he very much wanted to be part of a band—so much so that he called it Fleetwood Mac and gave the whole thing to me and John. So he was very generous.

The concert featured a mix of Peter’s contemporaries and younger musicians who were inspired by the early version of Fleetwood Mac. What was your initial vision for the show’s all-star lineup?

Every person on this list had a very driven musical and personal reason why they were on that stage [that relates to] Peter Green. It wasn’t a prerequisite, but it turned out that way. And they all have these incredible stories—like Noel Gallagher. You wouldn’t associate Oasis with Fleetwood Mac, or blues playing, but he said, “Way back when we first started, we would often play one of Peter’s old songs during the soundcheck.” He came out and really put his nuts on the line.

I had Christine’s support, and John Mayall from two years before; I had Zak on drums. I went to see Townshend and The Who and spent the whole afternoon while Zak was waiting to go on stage talking to him about Fleetwood Mac. I said, “Well, I’m hoping to do this show one day.” And he said, “Well, whenever it happens, you’ve gotta ask me to do it.”

Steven Tyler is a dear friend of mine and a huge advocate. About 12-15 years ago, I got to know him and I spent some time with him in Hawaii. And he said, “I don’t think there would’ve been an Aerosmith if it hadn’t had been for Fleetwood Mac.” Joe Perry had been asking him to play, on and off, for years. And, as the well-worn story goes, while he was walking toward the garage or the shed where they were practicing, he heard them playing “Rattlesnake Shake.” And he said to himself: “If this is the sort of shit that they’re playing, I think I’ll join the band”

And then, sadly, we lost Peter [this summer]. When the phone rang, I couldn’t believe it. He wasn’t ill or anything; though, he wasn’t super healthy. He just went to sleep. It was very sad losing him. Peter had no ego. He was aware of what we were doing. He didn’t come to the show—he was thinking about it but, ultimately, said, “I’ll see it when you’ve done it.” And, of course, he won’t. It’s one of the many twists and turns. We were lucky to even do this concert. If it [were scheduled for] four days later, then none of these people would’ve turned up [due to COVID-19]. A chunk of these people came from overseas—it makes me almost feel sick when I think about it, but we were all so lucky. This was probably one of the last shows on the planet.

Though you knew John was unable to participate, you were able to recruit the fourth founding member of the band, Jeremy Spencer, for the tribute. At what point did he decide to join?

I didn’t know Jeremy was going to be there until near the end; he was very withdrawn and just said, “I don’t know if I can do it.” And I said, “Jeremy, I’m actually not asking; I’m telling you.”

He said, “I don’t want to let you down.” I said, “Well, don’t. Sleep on it, and phone me up in the morning.” No one knew he was coming; we didn’t even have him billed. He blew everyone’s mind. Being onstage with Jeremy again was very apropos; he was the star of our show back then. The first album was heavily Jeremy Spencer. All the Elmore James stuff—that’s all Jeremy. It’s the same thing with the last album Peter made with us, Then Play On. He gave sweet Danny Kirwan—who also gets forgotten—a shot. And Danny was amazing—he used to come sit in the front row and watch Peter and the band play. Sometimes we’d give him a ride home in our van, and he’d go, “That was a good one tonight, boys.” Eventually, me and Peter tried to help him put together a band. But, we both just said, “I can’t think of anyone good enough to put in a band with him.” We sort of, simultaneously, turned around and said the same thing. At that point, Peter was starting to get a little bit itchy creatively. Jeremy was a thoroughbred and he had no real interest in doing something different, which was not a bad thing. But Peter was looking for a creative partner to explore some other musical things. So it worked out really well. Jeremy, of course, stayed in the band, but we added a third guitar player, which was entirely unique. So we were able to at least capture a few more moments with Peter before he made that journey, emotionally.

Peter suffered from metal health issues for decades. When was the last time you saw him?

Peter was very reclusive. On the last tour, I went out to his house and just sat with him. He liked painting in the kitchen; he was very quiet. He’d talk and then he’d get bored with talking. It was just about being there and sitting with him. I always thought that he would be OK again—and some part of him was OK. He was very objective about what had happened to him, emotionally.

Back in the day, I used to go on like, “He’s OK again!” I’d have these long conversations with him, and he’d be totally engaged and then he’d say something, and I’d go, “Ah, shit, he’s not back.” He’d say something completely esoterically fascinating, and always very truthful.

And so I just stopped being the cheerleader. As you can tell, I talk a lot and that used to tire him out. So I would just keep my mouth shut and keep at an arm’s length. There was a chap that looked after him—there was this neighbor who used to go and play guitar with him two or three times a week or just sit with him. They’d go fishing together. Sometimes I would be on the phone with him, and Pete would mumble something in the back like, “Hey, Mick, how ya doin’!?” That was Peter’s life.

But me and Peter, in terms of our dynamic, were always extremely close as friends. And I, not to get overly dramatic, had to sort of withdraw—like when you want to be in a relationship and the relationship isn’t working. Sometimes it’s mutual and sometimes there’s one person going, “I wish it was like it used to be.” And I was that person for years and years. Back then, I felt more of a sense of loss than I do now. Obviously, there’s loss in knowing Peter’s no longer here, but I had made my amends years ago. I knew I had to—it wasn’t even a question of giving up. It was just accepting something.

On Fleetwood Mac’s 2018-2019 world tour, you included a few selections from Peter’s era of the band in your setlists. It had been years, and in some cases decades, since you played those early tunes with Fleetwood Mac. How did they mesh with the rest of the show?

Neil Finn, [who joined Fleetwood Mac at the same time as Campbell,] did “Man of the World” on most of the tour, and we had “Black Magic Woman” back in the show. Stevie and Neil had fun doing that, and Campbell played the hell out of it on guitar. When we were rehearsing for the tour, Mike and Neil loved the old stuff. We did “Oh Well” [the rare song from Green’s time in the band that was part of Fleetwood Mac’s setlists for a period in the 2000s]. We even had some Bob Welch songs in there, until we realized that no one’s gonna know the songs! So, one by one, we knocked them on the head and only kept two or three in the show. But the enthusiasm to do all the old songs was very much alive and well. We got carried away—we rehearsed “Hypnotize” and had that in the show, and it sounded great. But as we got closer to going on the road, and even after we did a few shows, we felt it was too much information. And one thing we don’t have is a shortage of songs, my God!

It was pretty sweet to do a slow blues song during the show and it was hugely emotional. We didn’t know how much trouble Peter was in as young chaps. We weren’t equipped to know that he was struggling for probably a year or so before he decided that he couldn’t do this anymore. It’s the woulda-coulda[1]shoulda thing, but “Man of the World” is a crucifyingly sad song if you listen to the words. Every night on the last tour, that was a really heartfelt moment for me and John. It’s one of those songs where, it’s fair to say, it didn’t matter that most people didn’t have a clue what song we were playing when we did it. That song does something to everyone, even to people who don’t know what song they are hearing.

I noticed that years ago when Stevie was doing background vocals for Tom Petty; she would sing a couple of songs with him. Of course, Campbell was there too, and I saw them at the Hollywood Bowl. She hadn’t said anything and, in the middle of the show, Tom says, “We want to give you something by one of the people whose songs we loved playing when we were rehearsing as a young startup band.” And, low and behold, they did two Fleetwood Mac songs. I had never heard Petty do them before, and one of them was “Oh Well.” And the audience went fuckin’ apeshit. And I was quietly going, “I know they don’t know the song, but it’s OK.” There are certain things—the aesthetics, the tone—about that song that just connect. So we had the same experience, really. When you’re playing something that’s slightly estranged—and it fits in with the show and it’s received in a way where you know that you’re connecting—it’s sort of the extra magic in your evening.

You staged your Peter Green tribute right before COVID-19 paused live music around the globe. How have you spent the past few months, both personally and professionally?

Everyone has their own story. It’s like in “American Pie”—the day the music died. And it certainly goes right down through the ranks. We are in a band that is, like many others, blessed to have had continued success. We have lived out our dream and made more than a good living doing it. But take one short breath and there are hundreds of thousands of folks who were like us when we started who are now going, “What happened?” We’re all working players and being a working player—when you aren’t necessarily attached to success—is incredibly daunting at this moment in time.

Speaking personally, I live in Hawaii. I spent a little bit of time in LA to be near my ex-wife and children, and then I just thought I’d better go home. And then I took a breath. As I said, there are a lot of people who are in a terrible situation, and they don’t have even half of the luxury of sitting back and saying, “Well now I can do X, Y and Z” or “Now I can learn to paint or think about things that I should’ve thought about over the last many years.” I’ll say, mercifully and with great gratitude, I’ve done a lot of thinking and also stayed active by doing a lot of online stuff. I missed the editing of [the concert film] but now we are going to be doing a really interesting long-form documentary to go along with it.

I just talked to John McVie, the consulate road dog. I’ll often do a lot of the hustling around with Fleetwood Mac, making sure everyone’s wanting to do something and that their needs are being met. But I can’t do that anymore. John will occasionally phone up and ask me: “Do you think we’ll ever go onstage again?” And I went, “I don’t know,” and it’s pretty heavy to say that. But I don’t know.

The island is opening up—I have a great, funky restaurant here [Fleetwood’s on Front St.] that’s been closed like all of the other restaurants on the planet. But I often play there, and I have a great fraternity of incredible players on the island. So, musically, I know I’m not gonna be completely without that. I’m trying to be careful—a lot of us have been careful about what we do and how to do it. And then, as things open up again, you have to remind yourself not to be selfish about how you feel and advocate for the right things because it’s gonna be, by all accounts, a rough winter. And it is thought-provoking. I know people who have come in and out of it. And though no one directly connected to me, thank God, [has passed away due to COVID-19], I know people that know people who are no longer here. And not to be maudlin, but I’m feeling all of that. I’m just trying to gather a support team.

I’ve got a funny old barn that was full of stuff, and now we’re building out a proper studio there. It’s taking forever but that, to me, is really exciting because I know it will be my creative den. I’ve got other places to do that, but nothing so focused. Also, I’ve been plugging away online; I did something with Dave Mason a few weeks ago, where we did “Feelin’ Alright” with Sammy Hagar, Mike McDonald and all of the guys from the Doobies.

During the quarantine, Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” unexpectedly climbed back into the charts, bringing Rumours into the Top 10 again, thanks to a TikTok video where Nathan Apodaca longboards to the song. You also posted your own TikTik clip in response. That must have been one of the most surprising parts of the past few months.

No kidding! I had a lot of fun doing it. And Nathan is the sweetest man, and he’s been doing bits and pieces like that for years. There was a charm to it, and it was not all super slick or preconceived or anything. It’s just about doing it, and we had fun. I’ve done loads of interviews with him, and the end result is that the Fleetwood Mac audience lit up with all these 10-15 year olds. And that can’t be bad! It all has its lifespan, but it’s not going away any time soon. I’ve even got a new fan club in China. And certainly TikTok, as a format, should not be politicized, and it’s not MICK FLEETWOOD cynical. It’s just a whole bunch of people having kooky, nutty fun. And it wasn’t a moment too soon—being connected to something that’s a moment in time is just fun for people. So I’m a huge TikTok advocate at the moment.

I jokingly said to someone that works with Stevie: “I’m hoping Stevie is really happy right now because her song is blowing up.” The album is blowing up too, but “Dreams” has got a whole new life that is beyond belief. So I’m presupposing she’s a happy camper.

You mentioned earlier that you are uncertain, given the state of the world, when Fleetwood Mac would be able to return to the road. But do you think the band will try to convene in other ways while the pandemic continues?

You’re talking to the cheerleader here, so I’m never gonna say, “never ever,” with regard to either touring or the thought of making music. Of course, for me, it’s always something that you hope happens. But in the meantime, Stevie has a live show coming out so she’s been really busy. Neil Finn and Crowded House have made an album. Both Stevie and Neil were supposed to be touring this year, doing their own things. By nature, we did not plan to do anything as a band for a bit. So I was able to do this [film], and it was really nice.

I also reconnected with Lindsey Buckingham, and that’s been a nice connection to have. [Some of the animosity] has definitely gone away, and he actually reconnected with me when he heard that Peter had passed away. And we’ve had some really enjoyable, philosophically a-OK conversations. We know there were things that weren’t going right, and that were going right, and I get quietly reminded about that. That’s why, no matter what we were unhappy about, the reconnect is great. And also, when I’m doing interviews—as I am doing now—I will never fail to say that Lindsey Buckingham is a hugely important part of the Fleetwood Mac story. And I never fail to mention the importance of what he did and how important he will always be—his input helped perpetuate the whole creative process within the ranks of Fleetwood Mac. It’s a story that should never go away—just like Peter’s story. I still hold him in high regard. Both he and I are able to talk about all these things— these memories—as two people. It’s no secret that he and Stevie are like chalk and cheese; it’s just too much for them to coexist. But it’s nice to be through that period and to know that we’re talking and philosophically OK with everything.