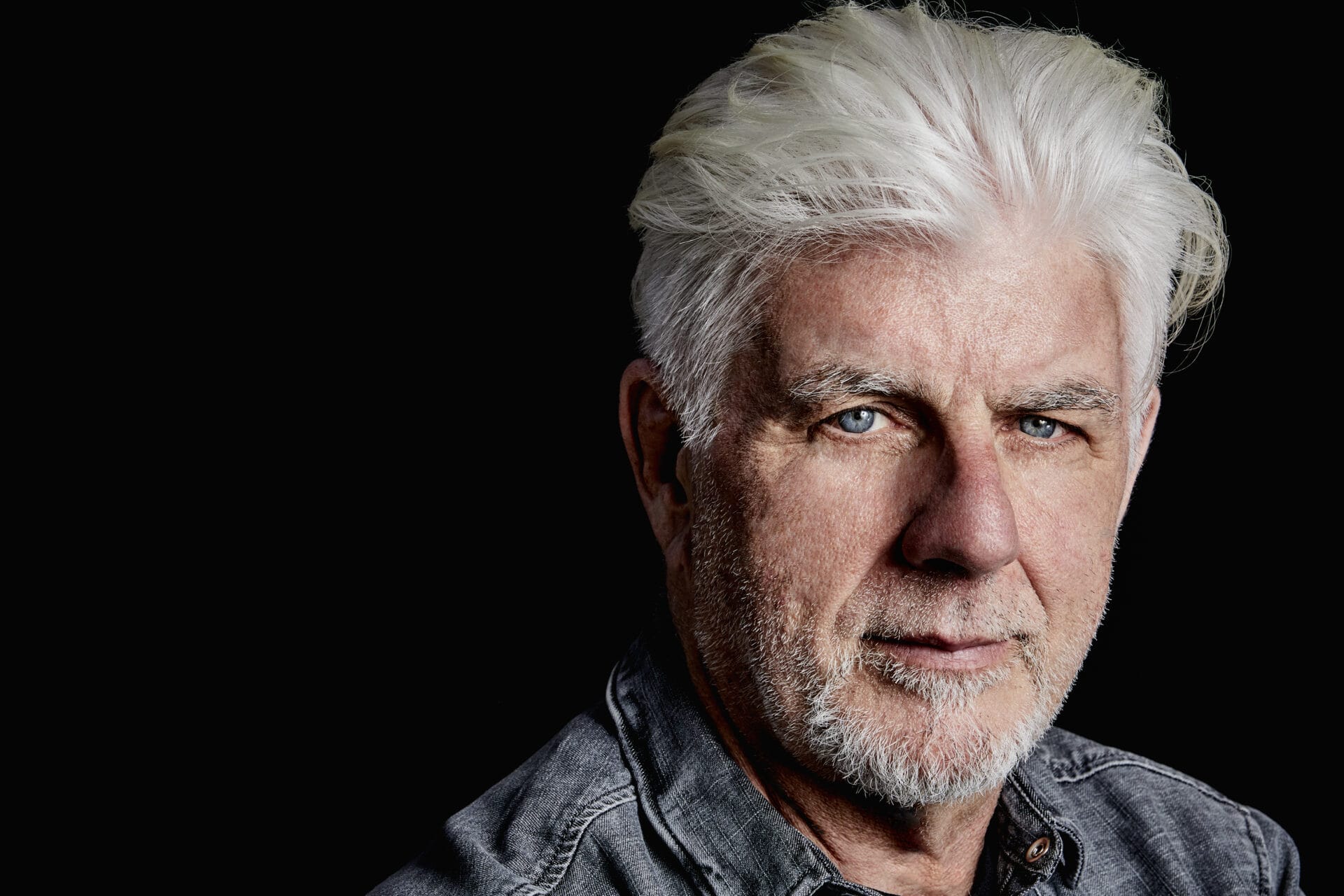

Michael McDonald: Minute By Minute

photo: Timothy White

***

“When I look back today, sometimes my life seems to be the result of a million random events—good and bad,” Michael McDonald writes in his new memoir, What a Fool Believes. “But I’ve come to see them all as pieces of the puzzle that ultimately is my story. Some pieces are smooth-edged moments of well-intentioned—if not always successful—efforts that are easy enough for me to claim, while other pieces are jagged and hard for me to even admit to myself, pieces that have taken me years to comes to terms with—much less recognize how they also fit. Those dark secrets, some of which I’m still wrestling with, represent a person that I was, but hopefully not who I am today.

“I’ve come to understand that those pieces all had to fall exactly as they did for me to be exactly where I am at this moment and that I’d likely never have gotten here any other way. I’ve discovered that it’s not necessarily life’s biggest achievements that most directly impact who we become, but rather the smaller, seemingly insignificant—yet vivid— memories that often conceal their importance.”

These eloquent words reflect the spirit of the work, co-authored by McDonald’s friend, comedian Paul Reiser. Still, there are plenty of lively, engaging anecdotes that chronicle McDonald’s time with Steely Dan and The Doobie Brothers, as well as his solo career. What a Fool Believes also vividly depicts the eras in which he grew up and then became part of the musical firmament.

McDonald further explains, “I wanted the book to have some kind of universality. I wanted it to be experiences that I thought other people could relate to. I thought that’s pretty much all I have to offer because how exciting is my story, really? But I also thought that I could lean into the randomness of how life is and how, throughout most of my career, my m.o. was that if there was a good way to screw something up, I would find it. In spite of that, doors would open, and in a moment of whatever cognizance I had, I would say yes instead of thinking about it too long or say no for whatever reason—I did plenty of that, but there were a few moments where I didn’t. I just kind of dove in and didn’t project too much about the outcome. Those seemed to be the times when I did myself a favor without realizing it at the moment.”

Did you have a particular goal in mind when you set out to write the book?

I was just hoping that the muse would hit us. Paul was the one who suggested it to me. We’ve been friends for about 20 years and he’s always had a fascination with ‘70s music. He would ask me a lot of questions about Steely Dan and The Doobies, and jokingly, one day, he said, “Why don’t you write a book so I can quit pestering you?”

I told him that people had mentioned it before, but I didn’t know how to go about it. I was afraid it would be something I would start and not finish.

Then he said, “I’ll help you.”

How lucky am I for this guy? He’s not just talented, but his discipline as a comic writer, a script writer and an actor—he really knows how to start something like this and get it done. So that was a real plus for me, but mostly it was his skills in this world that I leaned heavily on.

The way we started was he interviewed me and then we transcribed it.

We did it that way because we both wanted it to have the timing and the patter that it has when you’re telling a story. We knew it was better to start that way rather than writing the story because you can get redundant and overwrite things. I can write a short article like that, but in writing a book, it was nice to have those transcripts from the interviews.

We wanted it to be me telling the stories in my voice, and Paul did a great job of cutting, pasting and editing as we went.

After the interviews, I’d go off and write something for a couple of days that I’d send to him. Probably less than a third of that he felt was the real story, and he really saved me from a lot of mediocre details. He would say, “This is great, but this part right here, this is your story.” At first I would kind of bristle and go, “I don’t know man…” Then I would make myself read it a second time. Eventually, it got to where I didn’t even protest anymore because I knew if I read it twice, I would agree with him. So that kind of became our relationship. I would write a bit, send it to him, he would pare it down, and I would think, “Oh man, he just trashed my whole thing,” and then I’d read it the second time and go, “He’s absolutely right. Most of that was bullshit.” [Laughs.]

I have to say, he’s probably the person most responsible for this thing getting done. By the time we handed it in, the publisher said, “We’re going to kind of touch this up, but we don’t normally get something so finished.” I have to give Paul credit for that because he was editing the whole time as we went.

I just heard an interview with the actor Daniel Stern, who was talking about being on the set of Diner, and he mentioned that Paul had the quickest, sharpest wit. This book has a consistent voice to it, but when you were writing, were you tempted to have him chime in with a line here and there?

There were many times I wanted to steal his jokes but he would say, “No, you can’t do that.” It would happen when he would cut and paste something and I needed to come up with some kind of connecting thread. But we were able to keep it in my voice.

It was fun working with him. He was kind of a cheerleader and a truant officer at the same time. If I didn’t get back to him, he’d come looking for me on Zoom and start dropping me messages—“Let’s get back to it.” I appreciated that as much as anything that he brought to it. But again, all credit to him and his skills in writing a myriad of books. I was very fortunate to have someone with his skill set helping me do this.

When you finished the book and went through it from start to finish, did anything strike you or surprise you about the narrative?

When I did the audio book, that was the first time I read the whole thing through. We were so intent on getting it done, we were working section by section and pretty much focused on whatever part of it we were writing. So I never got the chance to go back to the beginning and read it all the way through until we did the audio book. That’s when I started to appreciate what Paul had brought to it with the form and shape of it, helping me put it all together. I was surprised at how well it read as a story. I had been worried about that all the way up to that point.

When I was recording the audio, more than anything, I was surprised at how tongue-tied I was with a lot of it. It’s like that joke on 30 Rock when the gal finally gets a movie part, and it’s in this film called Rural Juror—nobody can say the title, so it’s doomed to fail. [Laughs.] There were times when I was reading it that I couldn’t seem to get my tongue around a sentence the way I had written it.

I kind of started to panic a little bit as I read it, but Paul directed the whole thing, along with this guy that the publisher had as kind of a director for the reading. It was a week’s worth of reading, six hours a day, but Paul was great at that because that’s his forte. He’s an actor at heart and he helped with the lines in the book that were part of the story because I had forgotten how to say some of them conversationally. I was kind of emphasizing in all the wrong places, almost to where a simple sentence didn’t make that much sense anymore. So he helped me at that juncture and hung in there for the whole thing. That was a lot of hours to put in after the fact. He didn’t have to do that.

Since you mentioned Rural Juror, I should point out you have a much better title with What a Fool Believes. It almost feels inevitable. At what point in the process did you come up with it?

From the beginning, when we first started to write the book, Paul had suggested that as a title, and I said, “No, that’s just so obvious. We should come up with something more thought-provoking.” [Laughs.] I had no idea what that would be, but I thought it should be something that sounded a little more abstract.

However, the more we wrote the story, the more the title really seemed to really fit. Two-thirds through the book, as we were writing, I started to see the logic of the title, and it seemed to be a much better idea than I had previously thought.

It was like we couldn’t get rid of it. I tried to come up with something else and had any number of ill-fated ideas. At one point, I wanted to call it I’d Rather Be Lucky. He didn’t like that, and he said, “What a Fool Believes is unmistakably your story, and there’s a certain aspect to it that’s going to make the book. People are going to know what it’s about immediately.” In the end, he was right. The more we wrote, the more that story started to emerge.

Your career was well underway before you were 20 years old. When you were 15, you recorded with Steve Cropper and the Memphis Horns. Three years later, you were in the studio with Elvis’ TCB band. Do you think that was a factor of how the industry operated at that time? Or was it happenstance coupled with your gift as a vocalist?

I’m not really sure because, looking back, I wouldn’t bet that I had all that much to offer at the time. It wasn’t like I played piano that well. I played in bands and I sang—people seemed to like my voice—but it was a different thing back then. I don’t think I really had any idea who I wanted to be. When I made those records, I wanted to be Burt Bacharach and Tom Jones wrapped up in one, and I wasn’t nearly as good as either one of those guys.

But where I think I got lucky was that the guy I met who brought me to California, Rick Jarrard, was hustling too, trying to get his footing as an independent producer. He had been part of the RCA group and he’d done some albums for them and had pretty good success with Harry Nilsson, Jefferson Airplane and José Feliciano.

So I was kind of caught up in his wake, and when I came out there, we did a demo of an Elton John-Bernie Taupin song [“Take Me to the Pilot”] and got the deal with RCA. But what was the most fortunate thing for me was that he started hiring me to play sessions to keep me alive, really. There wasn’t a lot of advance on my record deal—about $3,000 that I received as a signing bonus. So that got me to California and into an apartment. And from there, he kept me working and it was an amazing amount of great experience that I did not deserve.

There’s a point in your book where you talk about your evolution as a songwriter and how, early on, you were more comfortable with writing in the third person and not being too self-revelatory. It reminded me of Walter Becker, who pointed out that he and Donald Fagen enjoyed writing songs in character because it allowed them to express certain sentiments that otherwise made them uncomfortable.

I think probably what appeals to most songwriters is the fact that they feel a certain freedom to say things that they may have difficulty saying themselves. Especially when guys write love songs or sad songs, it’s a place to go with those feelings that you don’t really find the opportunity to express in normal day[1]to-day life. A lot of us aren’t that good at talking about how we feel. It goes along with living in the real world.

Sticking with Steely Dan, you contributed iconic background vocals to some of their songs, including “Hey Nineteen” [“The Cuervo Gold/ The fine Colombian/ Make tonight a wonderful thing”]. I’m curious what went through your head as you were singing that.

To me, what I took from that song was it was the classic guy who’s getting too old to date young girls and doesn’t really know how to come to terms with that. He’s still trying to date young girls, only to realize that it’s an ever-widening gap, especially socially.

There’s a moment where you describe touring on planes with The Doobie Brothers in the mid ’70s and everyone is listening to the prior night’s show. How common was that practice?

We did it pretty much every day. I mean, for us, when we were on the road, we found that the show was an ever-changing, malleable thing. We would leave town with some idea of what we were going to do as far as a list of songs and a sequence of songs and the arrangements. But along the way, we got in the habit of boarding the plane the next day, putting on headphones and listening to the show from the night before.

It was always very telling. I think what created the habit for us was the things that we were starting to play in songs. You get out there, your parts are starting to change a little bit, and you’re thinking, “Oh, yeah, this is great.” Then you listen to the live show and, as many times as not, you go, “Oh, that’s not so great. I thought that was a cool part and, after listening to it from more of an overview perspective, maybe it’s not as great as I had thought it was.”

It was important for that reason. But we also would find that certain things would come up—somebody would play something and we’d realize that if we orchestrated it a little more with a few of us, it would be a cool section or a line or a theme to incorporate into the arrangement. So things kind of evolved out there by virtue of the fact that we didn’t seem to be able to stop listening to ourselves. We would play the show, we’d listen to it the next day, and then by soundcheck, some aspect of listening to that tape on the plane would rear its ugly head. [Laughs.] So we would kind of morph the show as we went, by virtue of just getting a little bit more perspective on it once we were out there.

You’ve done a lot of collaborative songwriting in your career. In Kenny Loggins’ memoir, he describes his experience of knocking on your door while you’re playing what will become “What a Fool Believes.” In your book, you complete the picture from your perspective. Can you describe how you approached that songwriting session, as well as the process that yielded the Van Halen song “I’ll Wait?”

I think the one thing about both of those situations that I take away is that they almost didn’t happen, or the randomness by which that they happened. With Kenny, that had been a germ of an idea and every time I played it for Ted Templeman, he would say, “You’ve got to finish that song, man. That’s a hit. I’m telling you, that’s a hit.” I was just playing the little piano intro thing and some of the words I had in the first verse. I would promise him that I was going to finish it, but for the better part of a year, I never did.

Then I was just kind of running through ideas before Kenny got there. I played that one for my sister, remembering how Teddy liked it, and I said, “What do you think about if I played this for Kenny?” She kind of shrugged her shoulders and was non-committal. It only happened because at that very moment, the doorbell rang. I probably wouldn’t have played it for him, given her reaction, if he hadn’t heard me playing it through the door. But when I went to the door and I started to help him come in with his stuff, before I said anything, he goes, “You were just playing something on the piano. Is that something new?” I said, “Well, yeah, I was actually maybe going to play that for you.” He goes, “Perfect, that’s what I want to work on first.” At that moment in time, it could have been a song we never wrote. But because he heard me singing and playing the verse melody, he had already written the melody that follows the verse—his mind had already gone to that. So he was actively writing the song with me before I even answered the door.

With the other one, Ted Templeman had sent me this track that Van Halen had cut, and they didn’t have a melody or lyrics for it. He said, “I mentioned to those guys that maybe you could come up with a melody and lyrics for this track.” It was a track the guys recorded that Eddie wrote the music to—kind of a chord progression and a form, but there wasn’t any real melody to it. It was just Eddie playing the guitar parts with the drums and bass.

So I got together at Ted’s office with David Lee Roth. I had written some lyrics, and the melody, then recorded it against the cassette that Ted gave me. I played this idea for David Lee Roth, but I really couldn’t tell whether he liked it or didn’t like it or what the deal was. I left it with them, though, and they cut it, which was one of the luckiest moments in my life as a songwriter because that album [1984] was huge.

Now that the book has been out for a little while, what has been the most surprising or gratifying feedback you’ve received?

For this thing to actually hit The New York Times best-sellers list, even for a short time, is not something I saw coming. Paul and I were both like, “Wow!” All of a sudden, I realized that the way I spent my pandemic was more than worthwhile. We both had realized we were out of work for a while, so we hadn’t approached it like we were hoping to write a best seller. We were just looking for something to do in our spare time, more or less. We were not really thinking that much about it and figured we could always pull the plug if it really wasn’t going anywhere.

So it was amazing to get good reviews and find ourselves on the list. It was kind of surreal, really. For somebody who suffers from imposter syndrome, that only complicated things for me. I don’t see myself as a bestselling author of any kind, but I’ll take it. [Laughs.]