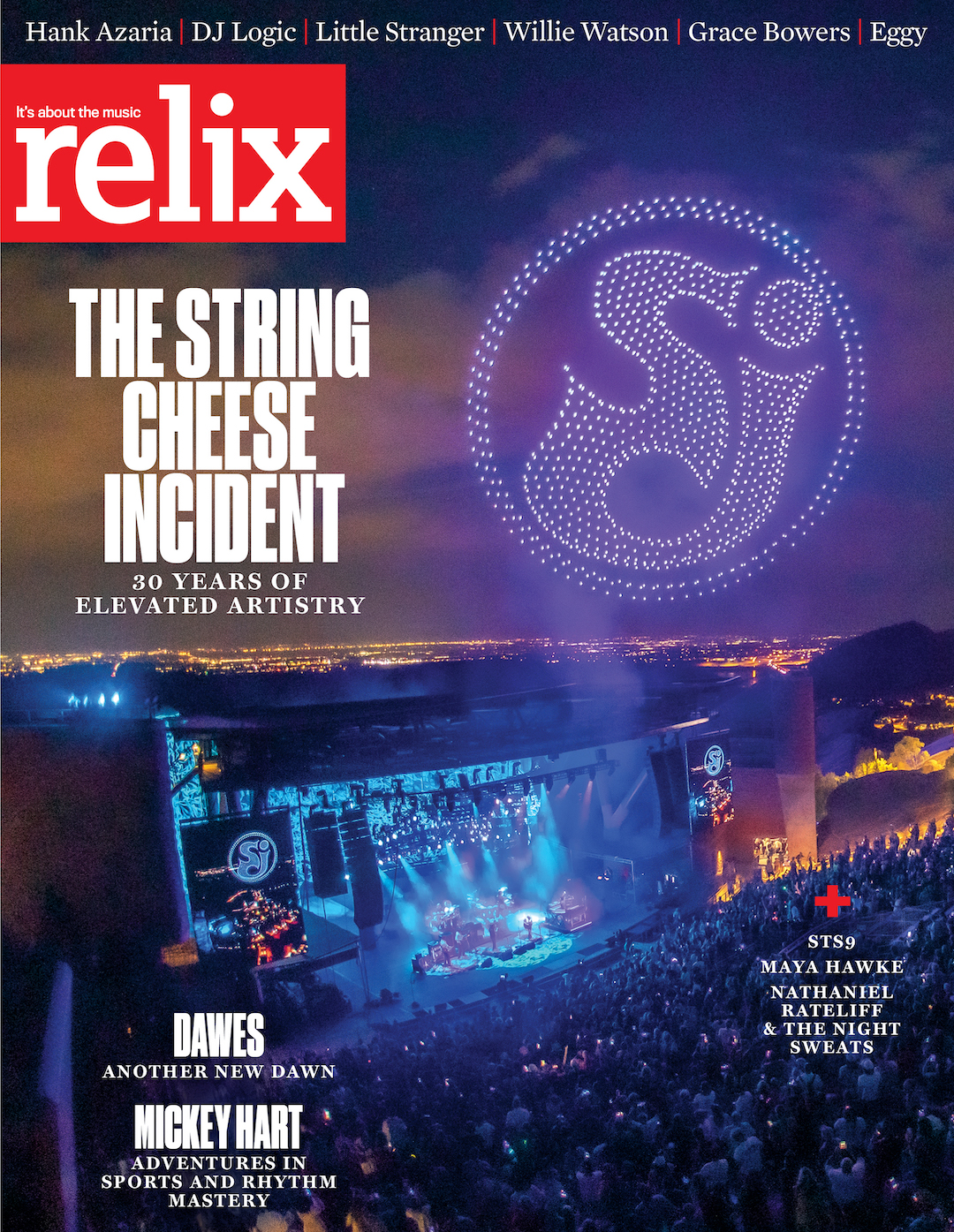

Margo Price: Freedom Fighter

photo: Alysse Gafkjen

***

As a little girl, I was plagued by rebellion. My straight blond hair grew long and unruly, into jagged corkscrews curls that turned light auburn. Elusive dreams beckoned me. My lust for life had me chasing after intangible things from the very start. I moved recklessly, running full speed ahead to what, I did not know. But I was always driven to do whatever I set my mind to, even if it meant burning some bridges along the way.

This evocative early passage from Margo Price’s new memoir, Maybe We’ll Make It touches on the poignant themes that inform the work. Price was an iconoclast from an early age, overwhelmed by emotion at times, as she pursued a personal creative vision that she was not always able to define or direct.

The book is lyrical, which should come as no surprise because Price is a gifted lyricist, adept at capturing small moments that feel large and revelatory.

Maybe We’ll Make It opens with an account of Price’s rural Illinois childhood, then goes on to chronicle the personal and professional challenges that ensued as she pursued the life of an artist—dropping out of college in 2003 at age 19 and relocating to Nashville.

Price struggled economically over the years to follow and experienced stretches of inner turmoil.

She also grappled with a country-music industry that imposed gender-based restrictions. Price now decries “this kind of false scarcity where if you’re a woman in this business, you’re made to believe that there’s only room for one of us.”

At times Maybe We’ll Make It is heart-wrenching, such as when the narrative focuses on her 2010 pregnancy, during which she learned that one of the twin boys she was carrying had a congenital heart condition that would prove fatal shortly after birth.

On other occasions, she paints an unflattering self-portrait that depicts marital infidelity and periods of alcohol-fueled dissipation.

Still, Price is a forthright and spirited raconteur with a quick turn of phrase. Her affable, earnest nature draws in the reader, despite her occasional transgressions (and, at times, maybe even because of them).

She remains committed to her craft and gradually gains traction—first through her band Buffalo Clover and then while fronting her group the Pricetags, both of which feature her husband, Jeremy Ivey. An indefatigable musician with an unfettered creative spark, Price eventually finds a match with Jack White’s Third Man Records. The label issues her acclaimed 2016 album, Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, which would be hailed as one of the year’s best albums by outlets like Entertainment Weekly, NME and NPR.

In the first chapter of Maybe We’ll Make It, Price describes a moment from her youth when Indiana Jones, a rescue horse she has adopted, unexpectedly breaks into a sprint while she is riding him. Price recalls, “Indiana jumped over ditches and rocks, rushed under trees. I was sure it was my time to die.” She eventually rolls off and lands beneath a barbed wire fence.

This incident supplies the name for her new podcast, Runaway Horses, which features conversations with fellow artists such as Emmylou Harris, Bettye LaVette and Bob Weir.

In the initial episode, Price acknowledges that while the experience with Indiana Jones was terrifying, it also left her with a “longing to feel that same unbridled freedom.” She adds that “freedom is exactly what I crave when I’m playing and when I’m listening to music. I just want a complete and total release.” She then invites her listeners “to sit right alongside me and some of my musical heroes as we talk about the search for freedom through our art.”

Price has continued to conduct that search throughout the albums that have followed Midwest Farmer’s Daughter. While 2017’s All American Made hewed somewhat closely to the traditional country idiom, it did so with a contemporary sensibility. 2020’s That’s How Rumors Get Started, produced by Pricetag alum Sturgill Simpson, pushed Price deeper into the rock realm. Her forthcoming album, Strays, which she recorded with Jonathan Wilson at his Topanga Canyon studio and will be released in January, is a kaleidoscopic achievement that incorporates elements of psychedelia.

While Price was writing the material for Strays, she was also working on Maybe We’ll Make It, and she explains, “I think that they started to mirror each other in a lot of ways. It’s funny because when I wrote the book, I did it kind of Jack Kerouac style, so it was like 500 pages of word vomit. There were no chapters. I didn’t know what was going on as far as the structure. It was just one big, long rambling story.

“Then, as I was going back through it and making chapter names, I was also naming songs. A lot of the songs were about that time in my past. I have found that the book and the album are both incredibly personal, and there’s a lot of vulnerability in both of them. But what I’m starting to understand is that there’s strength in vulnerability. I hope that both of them can convey that properly.”

You’ve mentioned that the book was prompted by your recent pregnancy. [Price’s daughter was born in June 2019]. Is there anything else that set it in motion?

I was going through this reckoning in my life around that time. It felt like I’d been moving at such a fast pace when everything took off.

It started as a way to keep my mind occupied and to keep myself busy. As I began writing it though, it really became this huge exercise in looking very deeply into my psyche to think about who I am and where I want to go from here.

I figured a lot of things out through the process of writing about my personality— my weaknesses, my flaws and my strengths. Going through it with my editor, some of it was embarrassing, some of it was painful, some of it was funny and lighthearted.

I feel like had I not written that book, I wouldn’t have seen a lot of things about myself. It kind of set the wheels in motion because at the time, I didn’t know who I wanted to be and where my career was going.

I really felt when I got pregnant, that things were over for me. I was in my late thirties, I had just gotten my career to take off and then I had to take all this time off because I had a baby—and then because of COVID.

I always had this joke that was like, “If I ever get my career off the ground, there’s going to be an apocalypse.” I felt like I could never be that lucky. Then, when COVID hit, I was like, “Damn, I hate that I was right about that. The world is going to hell in a handbasket.” [Laughs.]

As an artist, I feel like we’re going extinct because it’s really hard to tour. It’s hard to sell records now that streaming has come around and changed things.

So, it’s been a scary time. I just hope that I can continue to put food on the table. I don’t want to have to go back to waitressing again because I just don’t have it in me.

I don’t mean to be glib about this, but I have to say, you’re doing just fine. I wouldn’t worry about that.

Well, it’s like people who have body dysmorphia—no matter how skinny you are, you’re never going see yourself that way. I’m kind of like that because I felt like I was a loser for decades, so it’s hard for me to say, “Oh yeah, everything’s going to be fine now.” I have this thing in the back of my head that maybe is always going to be there.

On Runaway Horses, you speak with Amythyst Kiah, who is finding new sources of songwriting material now that she has eliminated some of her strife. Have you ever worried that personal contentment might impact your own music?

I definitely used to live and die by the belief that in order to make good art, you had to struggle because all I’d ever known was the struggling. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that’s not true.

I think getting rid of the booze was eye-opening for me in that way.

I have given up the self-destructive behavior that I was running with for so long and that said I needed to have sadness and pain.

I am getting to the point now where I would like to find more peace in my life because it’s hard to live in this world and be a highly sensitive, highly emotional person. I’m realizing that it comes from within myself, and I’m trying not to beat myself up all the time.

Was it your intent to share that message through the book?

I had been looking for a more peaceful way to live for a very long time. I’m still looking for that. I wanted to share just my little, tiny window of human existence because I felt like I had been going through my life feeling things too intensely, too deeply at times and knowing that other people feel that way too.

But I didn’t want this to be some kind of self-help book in any way. I hope it doesn’t come off like that because I am still very much floating through life not knowing the answers. But I think that once I was able to eradicate the booze from my life, it was such a key thing.

It was incredible, and I had this high from it. I had what they call “the pink cloud,” where you’re feeling a high from the absence of the substance.

All these other times when I had wanted to give up the booze, I had thought that my identity was just too wrapped up in it. I was like, “Well, I’m the bad girl. I’m the party girl, I’m the fun girl.” I thought I couldn’t take that away from my personality or demeanor because people were going to think that I’m not cool, I’m a fraud or I’m weak.

Then I kind of realized that it was the exact opposite, that it was the most rebellious thing that I could do. It was like, “Hey, I’m doing what everybody else is not doing.” So, I was able to share that and not feel self-conscious about it. I hope that other people can maybe pause and say, “Hey, maybe I can try that too. Maybe it’s not so scary or uncool.”

It’s different for everyone, but the way I quit drinking almost happened completely by accident. That might sound crazy, but I read a couple of books and they completely changed my mind. It took away my want for it.

Mushrooms had this profound impact in that way, too. I think it’s important to destigmatize psychedelics because they’ve helped me. If we use these plant medicines that were put on this earth by God, I think that we could absolutely change the world. Look at what they do to the brain, opening up new neural pathways and new ways of thinking, just new ideas in general.

But everybody is stuck in this path of drinking alcohol, which is the lowest vibrating frequency. And then you just pass out. I don’t understand why I was even hung up on it for so long and felt that it was something I had to do, because half the time I was doing it, I didn’t even like it.

I don’t want to sound like a teetotaler or anything, and hopefully, I don’t because I’ve just given up the booze. I am not sober. I’m still using cannabis and psilocybin.

I’m now going to pose a few of the New York Times Book Review’s standard “By The Book” author questions. What is your ideal experience in terms of where, when, what and how you prefer to read?

I like to read at night because it puts me in that place where I’m lucid. I have a lot of good writing ideas at night before bed and in the morning when I wake up. I’ve been trying to stay off the internet in the morning if I can. Right when I wake up, I either go out and do a two-to-three-mile hike with my dogs, or I sit outside, drink coffee and read a book.

As far as what I have been reading recently, I just read Positively 4th Street about Mimi Fariña, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. That was incredible. I had decided to read it because I have been writing more folky, acoustic-y songs again. So I would read that in the morning and I would be transported back to The Village. I loved reading about the Baez sisters growing up because I have two sisters as well. I felt like it fueled the kind of songs that I wanted to write.

David Hadju’s discussion of Richard Fariña, who is somewhat lost to history, is fascinating as well.

I never quite realized how much Bob Dylan took from Richard Fariña. I’m also getting chills all over my arms just thinking about how he died right after the publication of his book. [Fariña lost his life in a motorcycle accident following the book-signing party for Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me]. It makes me really emotional.

I just went to the Bob Dylan Museum in Tulsa. And granted, I could have stayed there for two or three more hours and looked, but I did not see any mention of Richard Fariña. I wished that I did. He was such a special artist and a phenomenal writer.

What else did you take away from your visit?

It was such a moving experience. I highly recommend both the Bob Dylan Center and the Woody Guthrie Center for anyone who’s visiting Tulsa. I had never seen an exhibit so artfully done. At the very beginning, when you walk in, there are all these different videos projected on the wall from these different eras and different interviews. From the moment I walked in, I just started bawling. I’ve been a Dylan fan—really a Dylan freak—for a long time.

Walking around there, I just felt so inspired and so moved by his drive to keep searching and to never get stuck with making the same things. He was always trying to find a way to get to a place of pure creativity.

I’m in New York right now, and I’ve been walking around Bleecker Street and I went up to Cafe Wha? and the MacDougal Street Ale House. It was really inspiring to be there, just kind of picking up the vibes.

Back to books, do you have a favorite memoir or a recent one that might have informed your own approach?

Patti Smith, Just Kids is my number one. That book made me feel things that I never had expected. [Laughs.] I’ve read that book at least five times, and I’ve listened to the Audible twice. I already knew her music but, after I read that book, I became a huge Patti Smith fan.

I also really love Willie Nelson’s memoir, My Life: It’s a Long Story, Ronnie Spector’s Be My Baby and Carrie Brownstein’s Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl. Flea’s Acid for the Children is so beautifully done.

Your book is so honest and direct about some difficult subjects. Did you anticipate that from the start or was there a moment of breakthrough?

The first draft of the book looked different from where it ended up. The first draft did not have my affair with my guitar player in it. The first draft did not have anything about my eating disorder. There was a lot that I was not divulging.

I think there was a breakthrough that happened after getting some feedback on that draft. I have a friend who’s a filmmaker named Joshua Weinstein. He wasn’t even my editor, I just gave it to him because he wanted to check it out. Then he was like, “I feel like there are things that you’re not saying.” There was also some anonymous feedback that we received from other people who read it, too.

So I sat down and had a talk with my husband, and we both decided that it was part of our story—what we had been through in our marriage and with losing the baby and how we both coped. I wanted to be transparent about what all of that looked like. A lot of the truth is ugly and a lot of my mistakes are hard to look at. But in the end, I’m glad; it felt like a weight off my chest.

I knew that some people were going to call me names and say, “You’re a bad mom, you’re an adulterer” or “You’re going to hell.” They will still potentially say that, but I’m owning my truth. I’m not going to sit here and worry about being judged. I’ve judged myself enough.

Both you and your husband are songwriters, and it seems like that’s helped each of you process certain events. I can imagine how that might serve as a mode of communication as well as expression. Do you ever impose limits?

We decided a long time ago that we were not going to limit what the other person wrote about. You might find some cryptic stuff in there and wonder, “Is that line about me?” I would ask my husband, “Is that line about your ex-wife? Who are you talking about here?” [Laughs.]

But we both agreed that we’re not going to judge each other for what we write, because so often as you’re writing, it’s a way to work through things in your own mind and a way to process your emotions.

If I didn’t have the outlet of writing or making music or creating art, then I wouldn’t be as healthy.

I think that everybody should write. There are times when something will really be weighing on me and where I will feel kind of stuck. Then, if I go on a walk in the woods, I’ll start processing things, and I’ll either get out my phone and make a voice message or I’ll come home, get out a pen and paper and just write. I won’t necessarily write a song, sometimes I’ll write a letter to someone but I won’t send it.

Being able to process my feelings through words and music has probably saved my life. That might sound cliché, but it’s been helpful for me and Jeremy.

These days, you’re also reaching people through your podcast. How did Runaway Horses originate?

The podcast kind of started accidentally. During the pandemic, I was doing something that copied Bob Dylan with his Theme Time Radio Hour. I did a bunch of episodes with various themes.

Then Sonos approached me and said, “Do you want to do a season of Runaway Horses with us?” I was like, “Yeah, of course.”

They had the idea for me to interview people. I was a little nervous because I’m not a professional interviewer, but it was so easy and so great to be able to talk to Bettye and Swamp Dogg and, of course, Bob Weir, along with so many of my heroes. It was crazy.

I imagine that the interviewing pressure was eased slightly because you already knew these people, which adds an intimacy for the listener. In the Bettye LaVette episode, you touch on some of her struggles but there is also such warmth, not to mention a post-credits vaping moment I’d encourage folks to stick around and hear.

She’s one of a kind. [Laughs.] Yes, it broke down some walls that I wasn’t going into an interview with people I had never had conversations with. In fact, Bettye LaVette called me on the phone the other day when my bus was broken down. We sat and talked for an hour—just shooting the shit—and then said, “Let’s maybe do a duet together.” She’s become my buddy. There were times when I was speaking with her for the podcast where we both kind of forgot that we were even being recorded.

What she had to go through breaks my heart. I know how difficult it’s been as a white woman coming up in the 2000s and 2010s. I hate to hear that she has struggled and, at times, continues to struggle given her caliber of talent. I value her friendship and admire her a lot for sticking to it because, as someone can read in her book [A Woman Like Me], Bettye has been through so much and she’s brilliant.

You’re a self-identified Deadhead. When did you first meet Bob and as you’ve come to spend time with him, has he had any impact on your own music?

I first met him at LOCKN’ Festival in 2017. I didn’t perform with him or anything. My booking agent, Jonathan Levine, has been working with Bob and the members of the Dead for years, and he wanted to connect us. I wasn’t going to be like, “Hey, can you introduce me to Bob Weir?” He said to me: “I really want you to meet Bob.” So he set it up and Bob took a photo with my mother and with my son, who was very young at the time.

I think what happened next was that he invited me to come sing with him at the Ryman. We did “Me and Bobby McGee.” We spoke about Janis Joplin and how he worked with her on that yodel part. They kind of figured that out together.

I love getting to spend time with him and hear his stories. He’s also led some incredible group meditations when I’ve come out to perform with him and his band. He’ll get singing bowls and we’ll all “Om” together. It’s such a cool way to start your show. The way that me and my band would have a moment of camaraderie before the set was shots of tequila or whiskey. Then I realized it kind of dried out my voice. So now we get together, we all put our arms around each other and we pray in a little circle before we go on. But Bob’s one level higher where his whole band is meditating together and getting on this vibration before they go out. Don Was and everybody are back there sitting on the ground with their shoes off.

By now, I have performed so much of Bob’s work, and we’ve covered Dylan together. We’ve done “Hard Rain” several times.

There were all these different minds that made the Dead what it is, but I love that he was really focused on the song, and how he rehearses ahead of time.

We performed at a Dwight Yoakam event at BMI and we did a song there where I was really having trouble with the key because it was low for me. Then, Bob was like, “You should just sing a seventh. That’s what Aretha Franklin did. Make up your own melody and just sing wherever you want.” It opened my mind in a way, and I use that trick all the time because there’s always times where I’m singing with dudes and the song’s too low for me. So I’m like, “Well, I’m just going to hop up there and make up some harmony melody.”

Let me ask you a question that you asked Emmylou Harris—in this instance it’s relative to Strays. What’s your process of choosing songs and determining the direction that your album is going to go?

I write songs in between album cycles. I’ll end up playing songs to audiences that I’ve written but haven’t recorded. That’s a great way to gauge if a song is good or not, by kind of test driving them on the audience.

Of course, I’m also bringing them to the band and seeing how they come to life there. I usually like to start with a theme or a direction, like genre. Even before Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, I had made a number of records. For instance, I had made a straight folk record that was called Bird in the Thorn. So it would be like, “OK, we’re going to make a soul record this time.” Or maybe Brit-rock or whatever.

This time for Strays, we took a big handful of mushrooms. Jeremy and I also listened to tons of records. We listened to Hypnotic Eye by Tom Petty. We listened to some Big Brother & the Holding Company. Of course, I was listening to Horses. I was listening to Bob Dylan records like Bringing It All Back Home. We let these different things seep into our subconscious the night before we started our writing process.

So from the very outset, long before you entered the studio, you had the sense that you would be adding some new colors to the sound?

I knew going into the writing process that we wanted it to be wildly psychedelic and push more into the rock territory that we had brought about on my third album—the one I did with Sturgill.

I’ve made two very straightforward country albums. Actually, I made three—one of them that I didn’t release was called Good and Evil. It’s a psychedelic country record that I recorded with a bunch of Nashville session players. Actually, I’ll call it a psychedelic gospel record, where basically the whole theme was that somebody takes acid and then realizes that all religions are one religion. [Laughs.]

But that album hasn’t come out. Then, with That’s How Rumors Get Started, I wanted to pivot a little bit more toward rock-and-roll and classic rock. With this album, I definitely did not want it to sound country; although, there’s definitely going to be people who will classify it as that. Then again, there is still a pedal steel, it is still the same band that made Midwest Farmer’s Daughter, and we’re all playing live. So we’re not completely reinventing the wheel, but we are moving in a new direction.

I feel really encouraged that this single that I’ve put out, “Change of Heart,” has been the most added song on Triple A Radio for the past two weeks. I think that the country music industry is unkind to women, so I needed to get away from it for a minute. I’m sure that I’ll go back to it at some point, but right now, I just need some space.

Just to pause on the psychedelic gospel record for a brief moment, do you think it will see the light of day?

I’ve been thinking about it. At first, the idea was that we were going to do a Neil Young-type thing and shelve it for a long time. But I don’t think that that’s going to be the case. Hopefully in the next three to five years we can release it.

What led you to work with Jonathan Wilson? Did he connect with these songs in a particular way?

I’ve always been a big fan of Jonathan Wilson’s production. I’ve also been a big fan of his solo work. I never had the chance to meet him, but as I started talking on the phone with a bunch of different producers—this was deep into COVID—I immediately felt a really calming spirit from Jonathan and so much enthusiasm about the songs. I sent him some pre-production demos. He also sent me photos of the studio that he just built in Topanga Canyon, and I wanted to be able to go out there and feel the vibe of that area.

The band and I had a spiritual experience making that record. I used session players on my last album. Then, as COVID was coming around, I felt like I needed to get back in the studio with my band because we had not been able to play music together in so long.

He saw the best in my players and was able to get the best out of us as a band. It was a lot of fun. We worked hard, but we also got to bond and be together. It was right after we’d gotten our vaccines so we were joking that it was like “hot vax summer” before the other variants showed up.

We were passing joints and just hanging out in the canyon. When you walked out of the studio you could go hike up in the woods. When you’re in a Nashville studio, it’s dark in there and then you come out and you’re in a parking lot. This was a whole different vibe. David Briggs’ old house was right across the street, and I would go wander off into the canyon and see rattlesnakes and all sorts of things out there.

Beyond the singles you’ve released, one of the songs that really struck me was “Light Me Up” with Mike Campbell. It starts out on acoustic and then, at one point, it just takes off. Can you talk about that arrangement?

When Jeremy and I first sat down to write that, it was one of the first songs that we knew was going to be for this album. We wanted to write something that was very Zeppelin—that was acoustic, but then just explodes. I knew my band could really pull that off.

So we started writing it and then we had all these different sections, all different chord changes and ideas. When we brought it to the band, they were able to solidify where everything goes because they’re such a huge part of the writing and arranging of my songs.

When we started writing that song, Jeremy was just doing this kind of fingerpick-y thing that sounds like the Grateful Dead’s “Friend of the Devil.” We were like, “What should we write the song about?” I said, “We should write a song that’s about making love. We need to write a song about sex. I feel like there’s just not enough women singing about their orgasms.” So that’s how that came about. We’ve been playing it live for about a year, and it really slays.

You’ve mentioned the role that live crowds have played in assessing some of your new material. Early on, you’d be playing to folks who had limited to no familiarity with your music. That’s changed over time; although, you’ve also done some opening gigs, where you’ve had to win over new ears. In January, you’ll be heading out on your first major headlining tour in a couple of years. Can you talk about your evolving relationship with your audiences?

I have some fans that I will meet, and they will be like, “I saw a Buffalo Clover show.” I’ll meet fans in England who knew who that band was and had bought those albums. I’ve had other people be like, “I saw you in 2014 when you opened for Old Crow, and I absolutely loved you.” When I was at my book signing last night, I had some people who had driven from very far and had been following me for a long time.

Of course, as the stages get bigger and as I am opening for people in larger rooms, sometimes I feel like I have to do so much to try to reach the audience. Especially if I’m opening for a larger artist, it’s a challenge to get up there every single night. At the beginning, they’re kind of cold or they’re not really listening, so I keep asking myself: “What trick can I pull out here? What song do I have that’s gonna connect?” I’m trying to read the room.

So I cannot wait to do these headlining shows because it has been a few years since I’ve really gotten out there and had a chance to play. I keep having this frantic paranoia and telling the people who work with me that I have to get out and tour because people are going to forget about me. But they’ve encouraged me to hold off on this sort of tour until this album comes out because my last one came out at the beginning of the pandemic, so those songs might feel old.

It’s been eating me up because I miss that feeling of playing headlining shows. I’ve done it sporadically. I played one headlining show in Montana at this dive bar a couple of months ago. It was incredible to have people in the crowd who were singing along to the songs. You can tell that it means a lot to them, and it means a lot to me.

I have been missing that connection with the fans onstage, because when I am just at home and living my career through the internet as many of us do, that’s not what fulfills me. Before the pandemic, I would always walk out into the crowd. It was something that I saw Charles Bradley do at the very end of his show. He hopped off the stage and went down in the crowd with everybody. He was hugging everyone and giving them roses. I was so moved by that. I can’t wait to get back out there and feed my fans in the same way that my fans feed me.