‘Love’ Stories: Chris Frantz Reflects on Talking Heads, Tom Tom Club, the Dead and the Power of Live

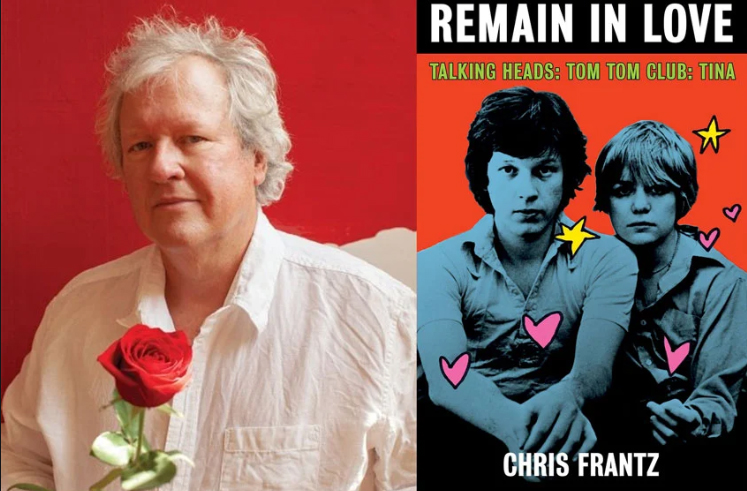

You’ll hear a lot of artists say, ‘I don’t like to dwell on the past. I just like to move forward and think of the future,’” Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club co-founder Chris Frantz observes while discussing the origins of his new memoir, Remain in Love. “And that’s fine—I think of the future— but I also like to remember the past, especially the parts that I feel were important. And, to me, Talking Heads was important.”

The book traces Frantz’s own development as a young drummer and art student. Eventually, he attends the Rhode Island School of Design where he meets Tina Weymouth, who not only would join him on bass in Talking Heads and later Tom Tom Club, but also would join him in marriage. Throughout Remain in Love, the drummer offers a refreshingly upbeat account of his journey. And, although he suggests that fellow RISD student David Byrne was not always empathetic or forthright, the book focuses on their collective triumphs rather than personal failings.

Frantz divulges another motivation in scripting the memoir: “There have been a number of books written about Talking Heads. None of them are any good, and the most recent one—which was some time ago now—was full of misinformation and, frankly, lies. So I thought, ‘I’ve got to do a book for no other reason than to set the record straight or tell my point of view for the fans.’ I started thinking about it back then, but I didn’t actually sit down and do the work until about two years ago. And it is work. Some writing days are better than others. You can’t wait for inspiration to strike. You have to sit down and do it, and sometimes the inspiration doesn’t come until after you’ve written a few words. Fortunately, I had enough time and a very patient editor who really encouraged me to be myself on the page.”

As you were writing Remain in Love, did you proceed chronologically or did you just set out anecdotes and then assemble them in some shape or form?

I did not work completely chronologically. The first chapters I wrote were about touring with The Ramones in Europe during the spring of 1977. We have a second home in France—Tina’s mother’s family home—though, unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like we will be able to go there this year. If I was in France, then I wrote about things that happened in France. If I was in the Bahamas, where we still have a little apartment, then I wrote about Compass Point Studios. If I was in New York, then I wrote about New York. Then, I assembled it in an order that made sense.

Speaking of your old New York haunts, what are your impressions of those same areas 45 years later?

Some parts of New York are just the same as they were, but most have really changed. They’re actually tearing down 195 Chrystie Street, the first building we lived in. We spent a lot of time in various lofts in SoHo and the East Village—the areas where our friends lived. And both of those areas are, in some ways, unrecognizable from what they once were. I love SoHo, but it’s a big outdoor shopping mall now. And very few people who lived in the East Village back then can even afford to live there now, unless they were lucky enough to get rent control, like Richard Hell. He’s in the same apartment on East 10TH Street where he was living in 1976.

In the book, you describe growing up as a suburban kid, which is quite a striking contrast from what you experienced while living in the loft on Chrystie Street.

We just had to be really strong. I always believed that we were going to be successful and that, one day, I would be able to live in a nice place that we could rehearse in—and that had heat. Fortunately, it happened very quickly for us. By 1976, we had a record deal and, by 1977, we were touring the world—and we only started in 1975.

CBGB quickly became Talking Heads’ home venue. You describe approaching Hilly Kristal to secure your first gig there. He allowed you to audition by opening for The Ramones on a Thursday at a time when the club only offered live music a couple of days a week. What do you think people might fail to understand about the venue during this era?

People fail to recognize how much of a dive it really was— in the early days at least—and how bad of a location it was in. For example, you couldn’t get record company people to come down and see you there. I couldn’t even get some of my friends from the Upper East Side to come down and see us there. It was too rough of a neighborhood.

I remember when we would play with The Ramones there, not that many people would show up. In the early days, there were maybe 30 people there for both bands combined. And I’d say to Dee Dee Ramone: “How come more of your friends don’t come down to see you?” And he said, “It’s too long of a subway ride. They don’t want to come to a dump like this.” It was a very challenging location to do business.

When people think of the music genres that thrived at CBGB, punk and new wave typically come to mind, even though the name of the club is an acronym for country, bluegrass and blues. Do you think that bothered Hilly?

Hilly was hoping to get country, bluegrass and blues people down because, though a lot of people don’t know it, Hilly was a singer. In fact, he had sung in a choir at Radio City Music Hall. He loved country music and he grew up in the tomato farms of New Jersey. It was wishful thinking on his part—nobody was really playing country music in the East or West Village at that particular point in time.

Richard Lloyd told me a story about walking down the Bowery with the rest of Television when they were looking for a place to play. They saw Hilly up on a ladder, hanging the CBGB’s awning in front of the club. They said, “CBGB, what’s that stand for?” He said, “Country, Bluegrass and Blues.” And they said, “We can play that.” And he went for it. Of course, they didn’t play any country, bluegrass or blues. But they did establish a residency there and they did build the first stage in the back corner.

Hilly wanted to have the bands in the front of the club, by the front door. And Television told him, “That won’t work. People will have to walk past the band to go in and out of the club and you don’t want that.” So they built the stage in the back. It was just a little tiny stage, barely big enough for a quartet. And it stayed that way until business started to improve for CBGB, around 1976-early ‘77. And then he built a proper big stage with a quite substantial PA system that sounded great. That’s when the crowds really started to come.

Prior to forming Talking Heads, while you were still at RISD, you founded the Artistics with David Byrne. In Remain in Love, you describe the music you played as “prototypical punk” and the setlist that you provide includes a number of raw rock covers. One exception is Al Green’s “Love and Happiness.” You’d later cover “Take Me to the River” with Talking Heads. What initially drew you to Al Green’s music and have you ever crossed paths with him?

I’ve never met Al Green in person. I’ve seen him perform, memorably at Jazz Fest in New Orleans about 15 years ago. It was on a Sunday morning, and he was one of the first people to play on the big stage. He had a white suit on and handed out roses to every lady in the front row; he was fantastic. This was the mature Al Green, not the young Al Green of 1974.

We all loved Al Green from the get-go. The way we would perform Al Green wasn’t quite punk, but it was definitely that cool, funky Memphis sound. We tried to get there but—even when we did “Take Me to the River” in our later years—we never had the same vibe as Al Green. As hard as we tried, it was still a bit of a reach for us to get there. But we loved the way he would get everything all mixed up—love and sex and marriage and cigarettes and money and God. It’s all rolled into one big Al Green spliff.

In your book, you quote a few lines of Julie Burchill’s review of a show from the 1977 European tour where you opened for The Ramones. She says that Talking Heads sounded like they’ve been locked in a closet with their Sam & Dave records for too long. Do you think that was a fair criticism?

I still laugh when I think of the image it conjures up, and I think she was right. We were such fans of soul music—we listened to soul music more than we listened to Roxy Music or David Bowie or anything like that when we were relaxing or making dinner. So I don’t think Julie was too far off there. As we grew older and more mature, we got better at playing our instruments; our technical abilities improved. But it was still a stretch to reach that gospel feel. We got there though.

Over the course of the band’s career, you also drew on a range of influences and reference points that often shifted from album to album.

It’s safe to say that we did not underestimate our audiences. They really rose to the occasion and were accepting of us. With Talking Heads, we often made a record that didn’t sound anything like the record that came before it. If you study popular music, then you know that you’re not supposed to do that. You’re supposed to be consistent. Basically, you’re supposed to get a sound and stick with it. Thanks to our fans, we were able to make some pretty challenging changes, and they came with us.

Jumping back to your RISD days for a moment, you describe seeing the Grateful Dead in a Quonset hut somewhere outside of Providence and being impressed with their sound system. Did you continue to see them on and off over the years?

No, although Tom Tom Club opened for the Grateful Dead on New Year’s Eve 1988-1989 at the Oakland Coliseum in Oakland, Calif. I had previously met Jerry Garcia in Montego Bay, Jamaica, at the One Word Festival in 1982. He was in really rough shape, but he was a nice guy.

Then, in 1988, Tom Tom Club did a run at CBGB, five nights a week for three weeks. The Dead were doing an extended run at Madison Square Garden at the same time, and Bob Weir would come down and see us. He’s a very nice guy and I’m pretty sure that’s how we got invited to open for the Dead.

After we played our set that night, one of their crew members came to our little dressing room and said, “The Dead would like for you to sit onstage with them while they perform.” We were like, “What?!” So we said, “OK.” They had a couch set up on the side of the stage, in full view of the audience, and we sat on that couch for their first few songs. Then, we had to split because we had two more shows to do that night. It was New Year’s Eve, and we were working hard at The Warfield Theatre. We did one show just before midnight and another show just after midnight. I don’t remember the second show that well. [Laughs.]

You named your band Tom Tom Club shortly after you gave that same name to the apartment in the Bahamas where you recorded your first record. When you named the apartment, did you plan for that to be the group’s name as well?

In the Bahamas, they don’t have street numbers, they have names. Every building has a name. Chris Blackwell was the landlord of this new building and Tina suggested that he call it Tip Top because it was on top of the hill. He liked that. Then I named our apartment Tom Tom Club—it was just something that came to me. I realize now that it was in a B movie called Expresso Bongo, which was about some beatniks; the club that the beatniks would go to was the Tom Tom Club. I guess that had been in the back of my mind somewhere and I really liked it.

In Remain in Love, you share a story about Talking Heads opening for Charles Mingus. That’s an impressive double bill, although certainly unexpected. Can you think of another curious pairing from the early part of your career?

There was a band called The Good Rats. They were from Long Island and were extremely popular. Somehow we got on the bill with those guys a number of times, and they’re audience really didn’t get us. The Good Rats were kind of like a cross between Twisted Sister and the Allman Brothers.

I can also recall a very early Halloween show when we were paired with Aztec TwoStep. They were very nice and amused by us. I remember them calling us into their dressing room to have a glass of wine after the show and they said, “You guys have something going on. I’m not sure what it is, but you’ve got something going on. But you really need to work on your stage clothes.”

Speaking of Halloween, do you recall your initial reaction after learning that Phish covered Talking Heads’ Remain in Light in 1996?

I heard about it after the fact, through some neighborhood kids. It was the sister of my son’s friend. She told him to pass along the message that “Phish covered your parents’ album in Atlanta.” I didn’t quite understand what that meant, but then she passed along a cassette tape of it. My feeling was, “Wow, that’s really something.” I later went out and bought the CD when it became available. Talking Heads never attempted to play that album in its entirety, although we did some songs. They really captured the spirit of it.

There’s one moment in the book where you describe the group as THE Talking Heads and you call attention to the fact that you’re doing so. Does it irk you when someone uses the definitive article before your name?

No, to me, it’s just silly. I’m pretty active on Facebook and I’ve noticed that on Facebook some people get worked up about it and say, “It’s not THE Talking Heads, it’s just Talking Heads.” While it’s true that we decided that it should be “Talking Heads,” from the very beginning, it’s never really bothered me as long as you get the “Talking” and the “Heads” in there.

You also mention that, at some point after concert tickets became increasingly expensive, fans started to conclude that higher prices also reflected the quality of the band. Though that makes sense, it’s also somewhat disheartening.

This sounds odd but it was Bette Midler who brought that to our attention. Our manager Gary grew up in the ‘60s and one thing his experience taught him was, “Don’t make it so expensive that the kids’ parents can’t afford to give them the money to come to your show,” because then, there will be no show. We understood that, so we always tried to keep our ticket prices as low as possible. For example, when we played those gigs at CBGB in 1988, the entrance fee was $5 and the T-shirt was five dollars. So for 10 bucks, you could see the show and get a T-shirt. If you brought a date, it was 15 bucks. [Laughs.] That was sort of our standard way of doing business for a long time. Then one day, Midler said to us, “You’re underpricing yourself. These tickets are way too cheap; you should charge more. You should charge $100.” I thought, “What?” But then I noticed all the other bands were charging $100, or maybe $300 or $600. So things got out of control and I think that’s too bad; it’s crazy. What band is worth $600?

We’re currently in a moment when music fans are longing for live performances. How would you characterize the power of live music?

This coming year is going to be a real challenge for live performers and the people who enjoy them so much. I also think about Lou Reed. In the very early days with Talking Heads, he said, “You gotta play live frequently. You gotta go out at least every year because people like to view the body.” I thought about what he said, and that’s really what it is. People don’t just want to hear you; they want to see you and check you out. They want to see what you’re wearing, what kind of guitar you’re playing, what you’ve done with your hair.

Back in the 1970s, there was more mystery to all of that. You’d buy an album, or hear a song on the radio, but you might not know what a performer actually looked like until you attended their show. That’s very different these days, particularly with fans posting live videos to YouTube. As a musician, what’s your reaction to that?

In theory, I like the idea that people can record a show on their iPhone and post it on YouTube. But the reality is: It’s often not a great shot, and usually the sound is not very good either. I prefer what it was like when The Rolling Stones or someone would come to town in 1972. You would look forward to the show for weeks or months beforehand. You would finally get there and you would sit through a great opening act like Stevie Wonder or Tina Turner. And then some booming voice would say over the microphone, “And now, ladies and gentlemen, the greatest rock-and-roll band in the world: The Rolling Stones!” The roof would rise and—for a few minutes—everybody would levitate. I’m not sure that really happens anymore; I guess it’s a bygone era, but I preferred that time.

I’m not so sure about doing concerts on Zoom. It’s a different thing. Then again, maybe somebody will have a breakthrough and make doing concerts on Zoom really hot and sexy.