“Look How Many Of US There Are”: Rosie McGee on Her Grateful Dead Photo Book and the Legacy of The Human Be-In

Rosie McGee’s new book has been over five decades in the making. As she writes in My Grateful Dead Photos and How I Came to Take Them, “I first met the Grateful Dead in November of 1965, when they unsuccessfully auditioned for Autumn Records at Coast Recorders under the temporary name of The Emergency Crew. Soon after that, they became the house band for Ken Kesey’s Acid Test events, and Phil and I started dating.”

The work opens with a picture of the band performing a DIY show for 100 people on March 25, 1966 at Los Angeles’ Trouper’s Hall—a performance space attached to a home for retired actors. In January, the Dead had traveled south from San Francisco, along with Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, to participate in some Acid Tests. Then, after Kesey fled to Mexico to avoid drug charges, the group remained for a few months, scrambling to find gigs.

The images contained in My Grateful Dead Photos, which are accompanied by McGee’s thoughtful musings, are intimate and revelatory. She maintained a close relationship with the group even after her relationship with Lesh ended, and the book spans from the Trouper’s Hall gig to a run at Shoreline Amphitheater in Mountain View, Calif., on May 10-12, 1991.

McGee, who was born in France and arrived with her parents as a 5-year-old immigrant, explains that she approached her photography without any commercial intentions. “I started taking pictures when I was 12,” she notes. “There was something compelling about being the girl with the camera and the act of being an observer. Then, as I got better, I started enjoying the technical and artistic sides of it. I was documenting my life with a camera and taking pictures of whatever I encountered. Well, when I was 18-19, what I encountered was the Grateful Dead. They were my friends, and I was taking pictures. It was an interesting scenario to be photographing a young band on their way.”

A serendipitous moment happened in September 1969, when Warner Bros. Records was on the verge of releasing Live/Dead and realized they didn’t have a photo of the group. The label called up to the band’s rehearsal space and McGee was enlisted to take the image that appears on the record. In My Grateful Dead Photos, she presents outtakes from the session.

By the mid-‘80s, some of her photos came to be licensed for other people’s books, and in 2013, McGee self-published her own work, Dancing with the Dead. Due to financial limitations, it began as a Kindle edition, although she eventually released a print version. This has led to a series of live appearances over the years, which typically feature a 40-minute photo presentation, followed by music from a Dead tribute band.

Her new fine-art book originated during the pandemic. She explains, “All of a sudden, my bookings got canceled, just like all my musician friends. Then I became aware of Kickstarter crowdfunding through Susana Millman and Bob Minkin, who had published photo books using Kickstarter. I reached my goal in six days, which blew my mind. I’d always wanted to do this kind of a book.”

She’s not only done it, she’s done it right, with glossy paper and high-quality printing. The Art Deco-infused cover received a bronze medal at the Independent Publisher Book Awards, while My Grateful Dead Photos and How I Came to Take Them won a gold medal in the Coffee Table Book category.

My Grateful Dead Photos and How I Came to Take Them which is now in its second printing, after selling out its first, is available online, while supplies last.

***

Other than the Live/Dead shots, your work was not initially accessible by the general public. At what point did that start to change?

My photos of the ‘60s, and particularly the Grateful Dead, turned into something that became desired, but I wasn’t thinking about anything like that when I was taking them. Then fast-forward a lot of years, and by the ‘80s, the band had become very well-known and books were being created about them.

In 1985, David Gans and Peter Simon put together a book called Playing in the Band and it was the first time that one of my photos was requested. That book was followed pretty quickly by Jerilyn Brandelius’ Grateful Dead Family Album, where she used over 30 of my images. That was also the first time that my writing was published—she asked me to give her some stories for her book.

So that has gone on since the mid-‘80s—the licensing of my photos for use in other people’s books. I didn’t even think about committing my stories to a book, but I’m a talker. I spent seven years working and living at the Grand Canyon in Arizona, and one of my friends there was a big Deadhead and he kept drawing stories out of me. I was reluctant at that time because I felt like I had moved beyond all that. But then, one day, he just pounded his fist on the table and said, “You have got to write a book! You owe it to us to write these stories down!” So that came together in my mind as, “OK, someday I’m going to do a book with my photos. I don’t know how. I don’t know when.”

The opening chapter captures the Grateful Dead at a moment where they remind me of any baby band at the beginning of their journey, standing onstage in front of a makeshift backdrop.

We put on that gig ourselves. You mentioned the backdrop—we went to the fabric store and got two lengths of psychedelic cloth to dress up the stage. It was pretty pathetic. We hung up the two pieces of fabric and that became the decor. I start laughing when I think forward to the elaborate Courtenay Tie-Dye backdrops in ‘85 at the Greek Theatre that were a hundred feet tall.

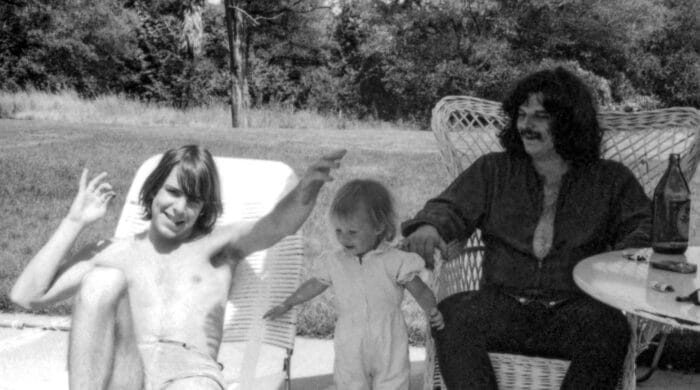

There’s another early image with Bobby, Pigpen and an infant Stacy Kreutzmann outside at Rancho Olompali. Pipgen can often appear intimidating in photos but, here, he’s anything but that.

Yeah, he was a very sweet guy. I mean, he had this persona just walking down the street and he also had his stage persona, but he was fairly shy. About a year later, when he was at 710 [Ashbury St.], he used to babysit Sunshine Kesey when she was just a couple of years old. I wouldn’t say he was a regular guy, but he was a sweetheart.

I took that one when we were by the pool. I had the camera in my hand, which I frequently did. I just saw the picture and took it.

Thinking back to the Acid Tests, as an attendee, is there any aspect of the story that hasn’t been fully communicated over the years?

Well, what jumped into my head was that there’s no way that those events can be communicated effectively. I’ve read a lot of stuff about them, seen films and watched people having panel discussions. But to my mind, it sounds like a bunch of mumbo jumbo and I was there. I experienced it a number of times. [Laughs.]

I’ve come to the conclusion that any LSD experience, and that includes the Acid Tests, cannot really be conveyed in words. If you’re trying to describe it to somebody, the listener can follow along if they’ve had the experience. If they haven’t, then nothing you can say is going to convey it and make you sound like anything except that you’re kind of out of your mind.

I’ve watched those films of the bus trip, Neal Cassady and all of that. I don’t see how anybody could make any sense out of it unless either they’d been there or they’d been on a similar trip where they could read between the lines and figure it out.

So while it’s not describable, the value that hasn’t been conveyed is what it afforded all of us who did participate in it to go forward from there. It was so wide open and so free.

At that time, the Grateful Dead were a garage band— whatever you want to call them—they weren’t the Grateful Dead in big, shiny letters. They were a bunch of musicians that had a band, and each one of them was equal to everybody else in that room. We were all just a bunch of young people having this event. It was a completely free environment where there was a bunch of gear and different stuff.

They could play or not play. People could dance or not dance. Neal could rap or not rap. Kesey could do this or not do that. There could be light shows or it could go dark. One of the things that went on was music, but it wasn’t a Grateful Dead gig where all this other stuff was going on. It was an event of its own where sometimes the Grateful Dead played and sometimes they just tripped.

In your chapter on the Human Be-In, you write, “With only local and underground publicity, the free event at the Polo Grounds attracted over 20,000 like-minded people! As we stood on the stage created from two flatbed trucks, all we could say was, ‘Wow! Look how many of US there are!!’” That realization must have been so wondrous and remarkable.

I’ve done photo presentations for years, and when I show photos of the Human Be-In, I talk about it as the absolutely pivotal event in the history of the counterculture.

That statement that I made of, “Look how many of us there are” was a revelation. It was also a milestone for all of us, because previously, there were these different what I call “enclaves” of likeminded people. There were the Berkeley politicos, the Haight-Ashbury people, the Palo Alto people and so forth. There was some intersection between people who knew each other but, basically, they were in what I guess we’d now call silos of smoking weed, liking a certain kind of music and sometimes dressing a certain way. Although, at the time, everybody’s clothing was pretty much what I call collegiate. It was way before tie-dye.

This event was pulled together through underground papers, word of mouth and posters in the headshops, of which there weren’t that many at the time. Then 20,000 people showed up, despite the limited publicity, and not really knowing exactly what it was going to be.

It was a combination of the politicos onstage giving speeches and the spiritual folks doing mantras and chants. Then the music started and everybody got up off the grass and started dancing.

But what happened was that the media was there—they had gotten wind of it—and they sensationalized it. It was newsworthy that this event had happened with such little publicity, so they asked, “Who are all these people and what’s going on?”

This was in January of ‘67 and the next thing somebody says is that the Summer of Love is coming up. Over the next few months, there was all this media attention on what was described as a movement, saying that everybody should get to the Haight-Ashbury. So eventually, a hundred thousand kids showed up for what I call the “so-called Summer of Love.” I always put it in quotes because, to me, the real Summer of Love was the year before, when nobody knew about us, and there were 200- 300 people in the Haight that were all friends and having a great old time.

You have some marvelous images of the band performing at the Columbia University Student Strike in ‘68. I’ve heard so many stories about sneaking the gear in. Did it seem like a caper to you?

I’ve been asked that a lot of times, and I don’t really remember. I don’t know if the gear came with us or the gear was there or the gear was brought in separately. The legend goes that we were smuggled in the back of a bread truck, and that could be the case, but there wouldn’t have been room for the gear. I do recall that we showed up and gear was there, so maybe it was two different vehicles. I really don’t remember.

I do know that the band was always up for an adventure. I don’t know all that was behind it but the student strike was a political act, and they were taking it very seriously. I believe it was Rock Scully’s idea for the band to play for the striking students. He was the manager at the time, and he made it happen. I suspect that he just came to the band and suggested it, then they said, “Oh, yeah, that sounds like a trip. Let’s go do it.”

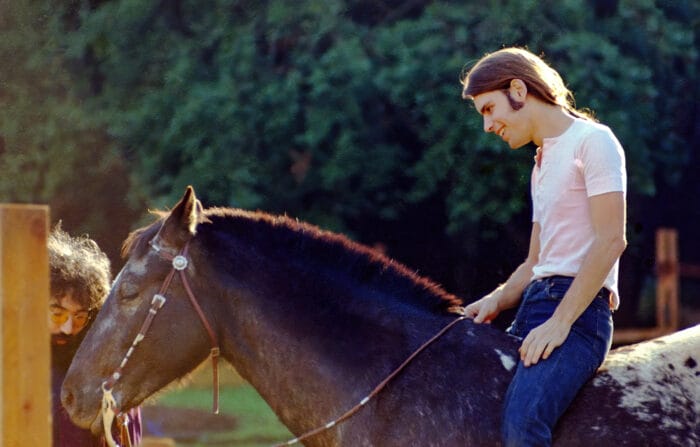

In your photos of the band members on horses at Mickey’s ranch, they all look comfortable, which somewhat surprised me.

Oh, they were not comfortable at all. [Laughs.] The thing with the horses was that Lenny Hart, who managed them for a short time before he absconded with the funds, signed a contract for them to appear in a movie called Zachariah. I don’t quite know the plot, but there was a band of horse-riding musicians in the movie. So they were hired to play this band, and they had to learn to ride. I think the only ones who already knew how to ride were Mickey, probably Billy and maybe Bobby. I don’t think the others had ever been on horses.

So Mickey arranged to have the band come over for riding lessons. He had additional horses brought over because there weren’t enough at the ranch for everybody. When I took those photos, I don’t know if they already had one day of lessons or if that happened to be the same day because it was so remarkable. But, thank goodness I did. [Laughs.] In the end, the movie was made without them. I don’t know if they were kicked off the movie or they declined it, but Country Joe & the Fish got the parts and played the band.

There are images of Candace Brightman and Betty Cantor-Jackson throughout the book, working as crew members. Not many women were out there on the road serving in a similar capacity at that time. Did it feel significant or notable?

I don’t think any of us, including the band, gave it much thought. They were supremely qualified to do the jobs they were doing, and the band always wanted the best to be on their crew or to do work for them. They always went for quality. They spent thousands and thousands of dollars improving their sound system and improving recording techniques and everything. They had the best people doing the work in every category, and along the way, some of them just happened to be women.

It wasn’t necessarily easy to be a woman in that environment, but they were respected for their skills, and they were kept on for their skills. Nobody was better than Candace at the time. And the same with Betty. She was excellent at her job. Why would they not hire her?

Although you attended the Europe ‘72 tour, you decided not to take any photos so you could savor the experience. Thinking back, what’s the first moment that comes to mind?

Well, having been born in France, coming into Paris and being onstage at the Olympia Theater probably is a highlight.

There were a lot of others. What’s going through my mind is one of the halls that had a built-in pipe organ. It was a beautiful building and just being there was extraordinary.

So it’s not just one thing. It was a two-and-a-half month tour of Europe with 40 of my best friends. We had a wonderful time, and I’m glad I didn’t bring my camera.