Little Feat: Time Loves A Hero (Relix Revisited)

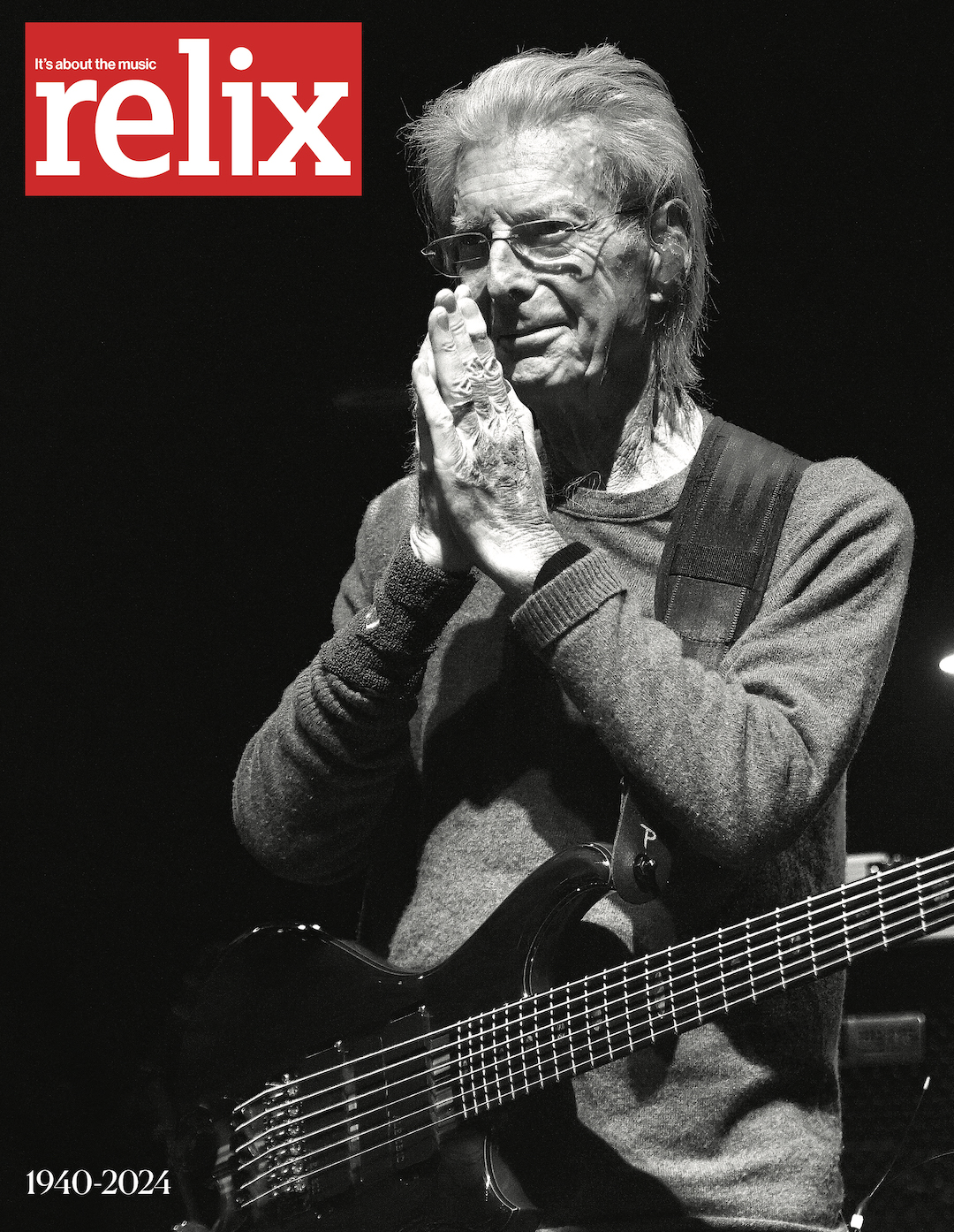

Today, in the wake of drummer Richie Hayward’s passing due to liver cancer, we offer up this piece from the Relix archives, which originally ran in April 1989.

They weren’t looking for a reunion. It just happened. That’s the way Paul Barrere puts it when recalling the events that led to the revival of one of the hottest bands of the ‘70s, Little Feat.

When the band split up in ‘79, after Lowell’s death, we never thought this would happen, getting back together," he says during the recent debut tour of the new Little Feat.

Lowell, of course, was Lowell George, who founded Little Feat in 1969 after leaving Frank Zappa’s Mother of Invention. George is generally credited as being the chief creative force within the original Feat, his quirky songs, funky rhythms and sneaky slide guitar lines having provided much of the band’s character. It was no wonder that the others thought they wouldn’t go n without him. So when George died of a heart attack during his first solo tour in 1979, the others packed it in and Little Feat went walking into the history books. It took nearly another decade before they realized what many of their fans already knew: Little Feat could exist as a band even without Lowell George. And they could still be great.

The reunion came about following a jam session which included the five surviving original members: guitarist/vocalist Barrere, keyboardist Billy Payne, bassist Ken Gradney (Bobby & the Midnites), drummer Richie Hayward and percussionist Sam Clayton. They’d been invited to perform at the opening of a rehearsal studio in L.A., one of whose rooms had been dedicated to George and included several choice items of Feat memorabilia. All five made it down, had a great time and…nope, you’re jumping ahead.

“It really was the farthest thing from our minds,” says Barrere about any thoughts of reforming the band that may have crossed their minds that night. “We didn’t walk away from that [jam] thinking, okay, this is what’s happening, we’re gonna put the band back together. But what that did was show everybody that we could still play together, that there’s still an energy there that’s unlike any other band.”

Energy is as good a word as any to describe Little Feat’s particular magic. Combining the blues with a New Orleans rhythm, acidified lyrical scenarios with good ol’ rock ‘n’ roll, a bit o’ country with an uncanny knack for taking a jam to stellar heights. Little Feat was an organic oasis in the processed, slick ‘70s. Falling somewhere between the Dead and the southern-fried blues-rock of Lynyrd Skynyrd and their like, the Feats were proof that there’d always be a place for world-class musicianship. Live, there were very few that could beat them, and although some of their records were flawed, all are still quite listenable today. And now, with the release last summer of Let It Roll (Warner Brothers), there’s a new slab of vinyl offering assurance that their decision to reform wasn’t a wrong one.

Some time after that 1987 jam session, it began to occur to the members of Little Feat individually that yes, getting together on a more permanent basis was an idea whose time had come. The surviving five each agreed to do it, and set about looking for new members to fill Lowell George’s considerably large shoes – even if the band was named for a set of peds that markedly offset his bulky frame.

The first man recruited for the job was Fred Tackett, a guitarist who was no stranger to the band, having worked with them on the Time Loves A Hero and Down On The Farm albums in the late ‘70s. The big question was who could possibly stand in George’s place, who could sing for Little Feat? The band considered big-name friends like Bonnie Raitt and Robert Palmer, both of whom go way back with them. But that was an unreasonable idea, as both had thriving careers of their own and couldn’t commit to a full-time gig with Little Feat even if they were interested.

Auditions were held but none of the contestants were right. Finally, Craig Fuller asked to try out. A One-time member of Pure Prairie League, Fuller had met Little Feat in 1978 when, as part of the Fuller-Kaz Band (with Eric Kaz), he opened for them on tour. Fuller had even written a song with Paul Barrere at the time, “Hate to Lose Your Lovin’,” which finally surfaced as the single on last year’s reunion album.

When Fuller came down to audition, however, most of the band members hadn’t even heard him sing, so they were skeptical. Once he opened his mouth, though, there was no doubt about it: this guy was the new Little Feat vocalist. Fuller snag enough like Lowell George that Bill Payne called it “eerie,” yet he had his own distinctive style as well.

Barrere remembers being unsure whether the others in the band would choose to hire Fuller. “The other guys in the band had to vote on whether he could be in the band or not, and the first couple of rehearsals you could see tears in their eyes. It was frightening. The first couple of times we played there were some old roadies and friends and they were spooked.”

Bill Payne was one who liked him, but it wasn’t until after the band told Fuller he was in that Payne realized some of the band’s fans might question their motives in signing on a singer who could be accused of being a Lowell George imitator. “It didn’t really dawn on me till later,” he says. “I’m kind of slow at some things. I guess for some people it doesn’t work but they’re small in number.”

Indeed. The excellent sales of Let It Roll and the sell-out crowds throughout the tour eased the band’s mind considerably. If there was anyone who didn’t think Craig Fuller belonged in Little Feat, they weren’t very vocal about it. Most of their older fans, it would seem, were glad to have them back and rocking in any form. The fact that they turned out to still have everything they had in the old days was a genuine plus. Another was that Little Feat was attracting a whole new audience made up of younger fans who missed them the first time around. Payne and Barrere believed that a good part of that crowd is comprised of Deadheads who’d heard about Feat but never got to experience them live.

“I think the Deadheads have a lot to do with it,” says Payne about their new popularity among younger fans. “They’re Feat Heads as well.”

“There’ a similarity between us and the Dead,” adds Barrere, “in that, even though we play the same songs in consecutive shows we never play them the same way twice. We kind of approach the music in the way the old jazz combos did back in the ‘50s. You have a set arrangement but within that arrangement you have freedom to blow.”

Actually, if there is any criticism of the recent Feat shows, it’s that they were almost too tight, that their mature chops and less volatile lifestyles didn’t allow them the looseness which marked the Feat concerts of the ‘70s. But Payne and Barrere don’t think that the band has lost any of its ability to surprise when they improvise. “In the old band,” explains Payne, “the music we were playing lent itself to stretched-out jams. If we were playing ‘Day Or Night” or “Day At The Dog Races,’ in those types of songs we let it loose. I think the band is playing better; there’s no question about it in my mind. Over the next few years there’s gonna be a lot of room to include other pieces of material, old and new.”

Unlike many other bands of the ‘60s and ‘70s that decide to give the world another taste – usually unwanted by today’s audiences – Little Feat is a band acutely aware of its own history, its place in the rock ‘n’ roll family tree and its own strong points and mistakes. Lowell George’s death shocked them but it didn’t shock them – they now know they should have seen it coming. And they knew it could’ve happened to them too – drugs and alcohol were always on the Little Feat dessert menu in those days. So they’re thankful to be around to have this second life, and they don’t plan to blow it.

This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the formation of Little Feat, a saga that’s nearly as interesting and convoluted as the band’s music. Lowell George got his start in show business when he performed a harmonica duet with his brother on television’s Ted Mack Amateur Hour, losing to a young tap dancer – among the other competitors that fateful day: a young puppeteer named Frank Zappa; more about him later.

In high school, in Hollywood, George played flute and, it’s been rumored, could also be found reading poetry in beatnik coffee houses to the accompaniment of black-turtle-necked guitarists. In 1965 George formed a folk-rock band called the Factory, among whose members was drummer Richie Hayward. A year later they shared a bill in L.A. with – guess who? – Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention.

The Factory only recorded one single in 1967 and then the group broke up. George briefly joined the Top 40 punk-garage band the Standells, who’d had a big hit with “Dirty Water” but were already past their prime. When Zappa asked him to join the Mothers the following year, he was more than happy to accept.

George didn’t last long with Zappa, either, only about a half year. But it was enough time for him to play on the Weasels Ripped My Flesh album and Zappa’s solo Hot Rats. At about the same time – keep this in mind if you’re following the time line here – the ex-members of the Factory were metamorphosing unto the Fraternity of Man, a band whose one claim to fame would be the dope lullaby in Easy Rider, “Don’t Bogart Me” (better known as “Don’t Bogart That Joint” ).

Why George quit the Mothers is a tale already well documented. Briefly, he’d offered Zappa a song he’d written called “Willin’” and Zappa said no thanks. Zappa also suggested that George put his own band together, so he did, taking with him Zappa’s bassist, Roy Estrada. On the drums, George recruited Hayward, and on keyboards Bill Payne, a Santa Barbara army brat who’d tried, but failed, to play his way into the Mothers. At the suggestion of Mothers drummer Jimmy Carl Black, who seemed to find something amusing in Lowell George’s small feet, this new quartet became known as Little Feat.

Although they had enough contacts in the music business between them to land a record deal, Little Feat decided to rehearse for a year or so before making a record. Finally, they signed with Warner Brothers and began work on 1971’s Little Feat, produced by Russ Titelman. Apparently band and producer never hit it off, but despite its flaws the debut album is fondly recalled by many. It was similar in many ways to the twisted blues being offered at the time by Captain Beefheart and Ry Cooder; when George sliced his hand open while working on a model airplane and was unable to finish up the record, which included “Willin’” (as did the second album and albums by Seatrain, Commander Cody and Linda Ronstadt).

A string of critically-acclaimed albums followed – Sailin’ Shoes, Dixie Children, Feats Don’t Fail Me Now, others – and there were changes along the way. Roy Estrada exited after the second album in 1973 and George took the opportunity to not only replace him (with Kenny Gradney) but to induct two other musicians into the lineup: percussionist Sam Clayton and second guitarist Paul Barrere.

Barrere, according to legend, had spent time in jail, and his input into the band was evident as early as his first appearance with them on 1973’s Dixie Chicken. Although the album had some weak cuts, it also boasted some gems, not the least of which was the title cut, which remains a favorite today.

Feats Don’t Fail Me Now, released in 1974, was produced by Lowell George (as was Dixie Chicken, Sailin’ Shoes had been produced by future Van Halen producer Ted Templeman). It features the now-standard “Rock and Roll Doctor” and came to a grand climax with a 10-minute jam of “Cold, Cold, Cold” and “Tripe Face Boogie,” two others still in the band’s repertoire. Their persistence had finally paid off: the album rose to #36 in the Billboard charts. And by then, Little Feat had amassed a reputation as one of the hottest live American rock ‘n’ roll bands going.

By 1975, Little Feat was quite possibly at its performance peak, but there were cracks in the seam that fans weren’t seeing. By giving up some of the writing chores to others in the band, George was allowing Little Feat to become more of a democracy but he was also losing his grip on the creative direction his band – and at the time they all agreed it was Lowell George’s band – was taking. The Last Record Album, released in 1975, was not the band’s final album; that was meant to be an in-joke of some sort. But in some ways it was the beginning of the end for Little Feat.

Time Loves A Hero, a 1977 album was produced by Templeman and was, like most of Feat’s recorded work, imperfect, especially in comparison to the band’s live strengths. And anyone who hadn’t noticed the tension within the band before its release should have gotten the hint when the album closed with a six-minute instrumental, “Day At The Dog Races,” from which Lowell George took a vacation saying he wanted nothing to do with the track.

Finally, in 1978, Little Feat released a live album, something their fans had been demanding for years. Because Little Feat was a prime live band, Waiting For Columbus is a fine live album, although one can only imagine what would have resulted it they’d used tapes recorded about three years earlier. The double-record set became Feat’s highest-charting record, reaching #18, and their only gold album. And that’s when Little Feat broke up.

It was never really made official, but Little Feat ceased to exist as a band by the beginning of 1979. In the early summer of that year, George did his solo gig, Payne and Barrere went out on the road as well, backing up Nicolette Larson.

Thanks I’ll Eat It Here was disappointing in light of the magic George had made with Feat. It featured little of his trademark guitar and too many contributions of other musicians, on lame cover songs. Whether Lowell George could have followed it up with something more representative of his talents can never be known, of course. He died June 29, 1979 in Arlington, Virginia, of a massive heart attack brought on by excessive weight and too much fun. The band was devastated.

“I was actually pissed off,” is how Payne remembers feeling. “Angry.” Barrere adds. “I didn’t know what to think. You go through confusion and anger and you wonder why something wasn’t done. You always think, was there something I could’ve done?”

What they did was to put together a benefit concert at the L.A. Forum for George’s wife and children; George had never taken out life insurance. They invited along Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, Nicolette Larson and the Tower of Power horns and just played their hearts out for three hours. Only after it was over did the reality of George’s death hit Barrere. “I didn’t stop crying for 45 minute,” he says. “It was like a big release, and I finally realized that the cat was gone.” Barrere also realized that it could have been him. ‘I was heavily into drugs and alcohol myself at the time and from that point on I went even deeper over the edge. You would think that something like that would knock you in the other direction but it didn’t. It took me a while before I realized I was killing myself too."

After that final goodbye, the members of Little Feat went off on their own for nine years. Payne piled up copious amounts of session and live work, playing with everyone from Bob Seger to Toto to Jane Wiedlin of the Go-Go’s. Barrere played with the bands Chicken Legs and the Bluesbusters. He made two albums with the latter and two under his own name. Hayward, Clayton and Gradney also had no trouble finding artists who wanted to borrow their chops. Then came their first gigs – at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival last year, to a wild reception. Then came Let It Roll. Little Feat was back. Bigger than they ever were.

" It’s possible that we could’ve put out this album and everyone would’ve said, ‘Ah forget it,‘" muses Payne now. "But they didn’t. I think if they had we might’ve given up. But the feeling was that if we put out something we were proud of, we couldn’t lose."

And the feeling was right.