“Lifelong Missions of Music and Activism”: Tom Morello Talks Rage, Joe Hill and KISS

“I had been rooting around in basements, attics and closets for a while and I found these incredible photos,” Tom Morello explains, as he charts the process of collecting material for his new visual memoir, Whatever It Takes. The book—which chronicles a life that has blended strident advocacy and musical expression—begins in Morello’s preteen years and shares some of his high school and college efforts, then builds chronologically through his work with Lock Up, Rage Against The Machine, Audioslave, Street Sweeper Social Club, The Nightwatchman, Prophets of Rage and The Atlas Underground. Given the range and ambition of these projects, it seems fitting that Whatever It Takes includes four separate forewords, from Michael Moore, Jann Wenner, Nora Guthrie and Chuck D.

“This has been one way to stay connected during the pandemic, at a time when there’s a lot less connection than there might otherwise be,” Morello continues. “Assembling these photos really made me reflect on my lifelong missions of music and activism and this seemed like the right time to share what I’ve discovered.”

During the process of creating the book, was there a particular holy grail image or artifact that you hoped to locate?

There are a couple of real watershed moments. When you’re living them, you don’t realize how important they are but, looking back at these photos—and in the context of the overarching narrative of the photo memoir—they stand out.

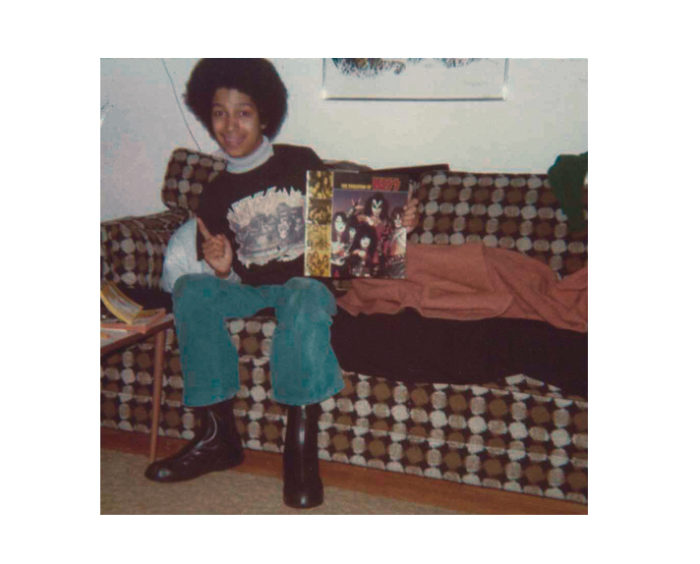

One is a photo early in the book. I had just returned from seeing my first rock concert— KISS in 1977 at the Chicago Stadium. The euphoric look on my face is reflective of my experience—the holy spirit of rock-and-roll had just entered me.

Then there’s another photo from five years later, moments before my first-ever performance. That was with my high school band, The Electric Sheep, which bizarrely also featured Adam Jones of Tool. I’m in my mom’s living room wearing a punk-rock shirt that is made up of a garbage bag and red electrical tape. I have exactly 100 safety pins in my pants and I’m wearing moccasins. There’s a picture of Stonehenge in the background and I’m ready to go do battle for the first time.

Did your experience at that KISS show set in motion the idea that you could play music for a career?

The KISS show made me love rock-and-roll completely, but if there’s a show that helped connect the dots, then it was The Clash at the Aragon Ballroom in 1982. Before then, the bands that I had admired were so out of reach. They were these almost mythical characters who lived these exotic lifestyles with $10,000 guitars and castles on Scottish lochs.

Then, I went to see The Clash. At the time, in my little punk-rock band, I had this Music Man amp on a chair in my mom’s basement. And when I saw The Clash, Joe Strummer—at the time, my favorite musician—had the exact same Music Man amp on a chair at the Aragon Ballroom.

When I saw that I no longer felt like this is something that maybe, one day, I could do. I realized I was already doing it. So that was the moment of do-it-yourself, punk-rock liberation.

In Whatever It Takes, you share the lyrics to “Salvador Deathsquad Blues,” which you describe as your first “political” song. That song was inspired by The Clash’s London Calling record. How old were you when you wrote it and can you describe your initial response to songs like “Spanish Bombs” on London Calling?

I wrote that when I was a junior in high school, so I was probably 17 or 18. By that time, I had already connected, sonically, with the Sex Pistols. And then, lyrically, The Clash opened up this new world. Before that, I used to think that great music had to be blues-metal based and had to be about the devil and groupies. I didn’t even realize that there was this huge wellspring of sounds and ideas that was just as great as any of the metal stuff. That resonated personally.

You also include the setlist from your first show with The Electric Sheep. Do you remember the initial song that you wrote and performed with the group?

I can still remember how that band was formed. It was within 24 hours of listening to the Sex Pistols cassette [Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols]. I marched into the drama club at Libertyville High School and announced that a punk-rock band was forming and I was going to be the guitarist. At the time, I didn’t know how to play a note on the guitar but I had a guitar in the closet. So I announced that I was forming a band and that no experience was required to join me. A few hands shot up—I believe the initial lineup was a saxophonist, a drummer, a singer and myself. We rehearsed in my mom’s basement and I think that the first song we wrote was called “Explosion of Punk.”

After high school, you attended Harvard, where you formed a band called Joey Thunder and the Electrical Storm. You mentioned that you performed in full-on spandex but that didn’t quite mesh with these political songs that you were writing about apartheid. Do you think that would still be true today?

I don’t believe that’s still true and I don’t believe that it was true then because I was out there in my spandex doing my best to sing antiapartheid songs.

Speaking of that spandex, one thing that the book clearly reveals is that I’m not hiding anything. There are various facets of my history that I fully embraced, that are not cool at all, whether it’s Dungeons and Dragons stuff or my appearances in multiple Star Trek episodes. [Laughs.] I think the only way to be an authentic artist is to be real.

I paid American money to see Dokken and Mötley Crüe—people who are fans of the more hardcore, anarchist element of Rage Against The Machine are aghast at that. But without that background, I wouldn’t have sounded like I sound as a player and I wouldn’t have been able to contribute to the chemistry of the bands that I’ve been in.

Rage Against The Machine first gained a sizable following in the U.K. Over the years, you’ve also really connected with audiences in Europe who might not be English speakers. What do you think accounts for that?

It all started because the FCC’s censorship restrictions are different here than they are in Europe. We refused to edit the lyrical content of our songs and you could say, “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me” on the radio and on MTV over there [from “Killing in the Name”]. You couldn’t do it here, so we were invisible in a way because we weren’t on the radio, we weren’t on MTV. But, the band connected overseas— in places where they could actually see and hear us.

Another thing I’ve found in my career as an activist is the importance of music as a uniting factor. I have played countless shows at demonstrations, concerts, charity events and whatnot in front of non-English speaking rioters. But the one thing that I have found is that there’s something about a tribal gathering with a beat and an overarching message of solidarity that feels like the truth. That engenders solidarity like nothing else and it really does help steel the spines of people who do the real grassroots work for change.

After college, you moved to LA and joined the band Lock Up. To what extent could you express yourself politically in that group?

I moved to Hollywood with some dreams of the Sunset Strip—places like Gazzarri’s and the Whiskey—where my favorite metal bands would play and I hoped to join their ranks. However, I realized that it was actually a very different world when I moved out here. The ads in the papers were for specific physical types—your hair had to be exactly this and your cheekbones had to be exactly that. None of it was me.

I remember this one night at the Whiskey, watching the latest up-and-coming hair band. I think it was Jetboy on a bill with Faster Pussycat and, as I was watching them, I came to the realization: “I’m not going to have a career. I can play circles around those guys but, apparently, that’s not what it’s about.”

However, unbeknownst to me, there was also an East Side underground scene. That was the scene of Jane’s Addiction, Fishbone and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, where you didn’t need a particular hairdo for admittance. It was this dark, awesome underbelly of Hollywood, filled with people who were deeply intellectual and artistic. That’s where my musicianship was appreciated and people didn’t care how long my hair was. They were accepting of me, whereas the Sunset Strip had slammed the door in my face. I found my way into the scene and joined my favorite local band Lock Up.

I tried to shoulder some political stuff into Lock Up. But, when I joined, they were already an established band of older guys. I was sort of the young, hotshot guitar player in that band, and I was just very fortunate to be there.

When you first relocated to the West Coast you reconnected with Adam Jones. You’ve mentioned that, during this period, you practiced guitar eight hours a day. Did the two of you ever sit down to swap ideas or just jam?

Adam was one of my roommates when I first arrived in Hollywood. We were just a bunch of dudes, all living in an apartment together, staying up late every night and watching Star Trek reruns. But, at the time, Adam had a successful career as a prosthetic makeup artist. He worked for Stan Winston Studios and worked on the Jurassic Park movies and on the Freddy Krueger movies. So he wasn’t a musician at the time. He kind of had his dream job making Freddy Krueger masks and dinosaur casts and whatnot. It wasn’t until later that Tool formed.

In describing the early days of Rage, you observe, “The idea of a record deal wasn’t in our universe.” Do you think this had an impact on the music you were writing at the time, either directly or indirectly?

Absolutely. It was the career implosion of Lock Up that freed me. Until then, I had the dream of moving to Hollywood and becoming a rock star. Then I was in a band that got a record deal and that was the dream, which became a horrific nightmare. That band experienced every shafting that you’ve ever read about in the history of rock-and-roll. I felt like I’d had my grab at the brass ring and I’d missed it. At 27 years old, I was done; I was not going to be a rock star.

However, while I was not going to make albums, I was still a musician. So it freed me in a way, and I was like, “Well, if I’m not going to make it, then I’m not going to do anything more to try to make it. I’m just going to make music that’s authentic.” I was blessed to find three other musicians who felt similarly. That’s why we were able to make that music in this void of any expectations—other than that we wanted to be fulfilled personally and artistically.

You share a story in your book about the Beastie Boys opening up for you. You write that they “played 10 of their biggest bangers in a row and destroyed the place. We opened with a 14-minute Allen Ginsberg poem and a lot of deep cuts, which were met with relative indifference. It was an important lesson that informed every setlist I’ve written from that day forward.” You’re a big sports fan. Do you think that competitive nature spills over onto the stage?

Absolutely. You never want to be the second-best band on a bill. That’s how I look at it. On any given night, I want to be the best show that anybody’s ever fucking seen and leave no doubt in anyone’s mind that that is the case.

But the Beastie Boys came out and were one of a handful of bands that ever kicked Rage Against The Machine’s ass. So I planned so hard for the next time that we saw those guys and, when that happened, they were so Zen that they made their setlist in alphabetical order. They couldn’t have cared less. It’s like I was all steroided up for the next meeting, thinking, “We’re going to take them down” and they were having a nice time. [Laughs.]

Jumping ahead to your 1996 appearance on Saturday Night Live, Steve Forbes was the host. His world view stands in stark contrast to that of Rage Against The Machine. Did you get the sense that this was an intentional pairing?

There is no question it was done intentionally. He had just dropped out of the presidential race as the Republican candidate. He was known as this archly conservative, stiffneck, corporate politician, and then there was Rage Against The Machine. And it all blew up in everyone’s face.

As part of our stage setup at the time, we had these upside-down flags on our amps and, during the rehearsal, they said we couldn’t use them because they would be offensive to both the host and their corporate sponsors. And, we sort of looked at each other and said, “Don’t they know that our most famous song says, ‘Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me?’ So our crew put the flags back up moments before we went live and there was this physical altercation on the stage because their crew fought with our crew to take them down.

So we played “Bulls on Parade” and, afterward, there was a bit of a skirmish backstage and we didn’t get to play a second song. We were summarily dumped on the sidewalk outside of NBC studios.

What I remember about that episode is that Steve Forbes was not a good fit. He’s not an actor and he didn’t seem to have the proper comic sensibility.

He was terrible. What was funny is that they wanted us out of the building as soon as possible and their excuse was: “Look, we’ve decided to add another sketch with Steve, so we’re gonna cut the second song.” And we were like, “You’re going to add another comedy sketch with Steve Forbes rather than have Rage Against The Machine play? OK, I see what you’re doing here…”

Speaking of presidential candidates, your video for “Sleep Now in the Fire” [released in 2000] includes someone holding a “Donald Trump for President” sign. What are your thoughts looking back on that?

It was a very historic day for us, it was the day we met Michael Moore. I was a huge fan of his work and the question that I couldn’t wait to ask him—given the audacious political stunts in his TV shows and movies— was how many times he’d been arrested. When he told us that he had never been arrested before, I jokingly said in the trailer, “Well, you’ve never worked with Rage Against The Machine.” Cut to three hours later, and Michael was dragged away in handcuffs and the band stormed the New York Stock Exchange.

There are some days in any job, I suppose, where you know what the parameters of the day are going to be. In rock-and-roll, it’s: “We’re going to do a soundcheck, there’s going to be catering and then we’re going to play a show. It’s probably going to go well, and then we’ll move on to the next city.” But on that day, we had no idea what was going to happen. I mean, Michael’s direction was very simple. He told us: “No matter what happens, don’t stop playing.” And so, despite the fact that the director was put in a paddy wagon, we attacked the New York Stock Exchange and the riot doors were brought down. But we just did our best to keep the beat going.

What’s your response to the clip that was released in November of two Trump supporters dancing to “Killing in the Name?” I suppose, as an artist, you want your work to resonate but it just seems so antithetical to your intent.

On the one hand, I think it’s a testament to the fact that Rage Against The Machine is a great fucking rock-androll band, and that people are drawn to the music, irrespective of the color of their politics. Now in some cases, we’ve found that people are tone-deaf or so willfully ignorant that it’s outrageous and comedic. There’s also the case of Paul Ryan [the Republican former Speaker of the House] who said Rage Against The Machine was his favorite band but he’s worked his whole life as the epitome of the machine that we raged against.

So the way I look at it is that the couple wouldn’t be having their awkward drunken mosh pit to a Noam Chomsky lecture, so it takes some pretty kick-ass rock-and-roll to make fools of that magnitude get down. [Laughs.]

Your book includes a photo from your recent Atlas Underground project, which pays homage to an image of the activist Joe Hill facing a firing squad in 1915. I think that, for most Americans, Joe Hill is lost to history. How important do you think it is for people to learn about him?

Joe Hill is my favorite guitar player, even though there are no known recordings of him. He was the poet laureate of the militant working class in early 20th-century America. He’s the template for everything that I try to do as a musician and as an activist. The idea is to walk it like you talk it and, while a political pamphlet might be read once, a song will be sung over and over again. A song can unite people of diverse backgrounds—creating a tribal gathering with the message of solidarity in a way that nothing else can. That’s the message of Joe Hill’s music and that’s why they killed him. That’s why people are still outraged when music in 2020 rankles their political sentiments.

This period of quarantine had led many people to reflect on the role of live music in their lives. Can you share your thoughts on the power of live?

The power of live music, for me, has been transformative. On that first night with KISS, I became inhabited with the holy spirit of rock-and-roll. Then, seeing The Clash at the Aragon Ballroom made me realize that there was a path for people who thought like me—who colored outside the lines—to become musicians In my own career, I’ve tried—at every show that I’ve ever played—to create a little bit of the world that I’d like to one day see. I curate the sonics and visuals to help create a community each night. It’s my vision of a future planet that’s decent and humane—and that has a rocking soundtrack and an awesome mosh pit.