Kamasi Washington: Dream State

photo: Vincent Haycock

***

It was 2021, everything was locked down, thanks to the pandemic, and Kamasi Washington was out of his element. “I have all this new music that I’ve been writing, but I don’t know where it’s going to go yet,” he told this writer in an interview at the time.

Washington, the saxophonist, composer and bandleader, had been charging ahead, practically nonstop, since the 2015 release of his three-disc breakout album The Epic— his first proper full-length release for a record company. It had made such an impact that some critics and fans credited Washington with singlehandedly revitalizing the popularity of jazz, a genre that hadn’t exactly been dominating the music news (or sales charts) in recent decades.

Three years later, Washington returned with Heaven and Earth, two discs this time, released together but considered by the artist to be separate entities. Both The Epic and Heaven and Earth consisted of music that Washington and a tight cabal of Los Angeles-based musician friends—who call themselves the West Coast Get Down—had been crafting for years. They had amassed so much material, most of it fashioned from loose, continually evolving jams in the studio, that the recordings not only filled five discs’ worth of Kamasi Washington albums, but also projects by some of the other players as well.

After Heaven and Earth, that well had finally begun to dry up, and the musicians looked forward to writing and recording new compositions. But COVID had other plans.

“When the pandemic happened,” Washington says now, “there were two solid years of waiting to get back into the studio. I was itching to get in there.”

Finally, as the threat of the virus began subsiding, Washington and his crew were able to reconvene. The result, Fearless Movement, was released this May on the Young label. It’s also two discs, housing a dozen tunes. At 86 minutes, it’s actually Washington’s shortest major release to date, but there is much to savor. The new pieces—10 of them credited to Washington and/or various collaborators, the other two covers of songs by the ‘80s R&B band Zapp and Argentine tango master Astor Piazzolla—are rich and diverse, crossing genre boundaries and showcasing the contributors’ individual gifts and virtuosity. More than two dozen musicians— some of them were regulars providing instrumentation, others were one-off guests, including several vocalists and rappers—joined Washington in the making of the recording.

The album, according to Washington, marks the beginning of a new era for his music. The title, Fearless Movement, he says, “comes from the idea of moving forward, not being afraid to change. But it’s also [about] a very inspirational energy that I was pulling upon when we were recording this album.”

That energy, and the sense that he is stepping into new, uncharted territory, can, in large measure, be attributed to his becoming a father during the making of the record. Washington says, “That’s a huge part of it, just feeling connected to the future. You don’t realize until you have children how it makes you feel. My daughter’s going to live on past me; she’s going to be in the world when I’m gone. It’s not like I didn’t care about the future of the world, but it puts it in a different perspective. I’m feeling a very personal connection to the future, a future beyond myself.”

Astute readers of album credits will notice that the second song on Fearless Movement, “Asha The First,” is not only named after Washington’s daughter, but also gives the toddler a co-writing credit. There’s a good reason for that: At age 2, she came up with the main riff in the song.

“That was a beautiful moment,” Washington says. “She already has that fearless energy. She loves music, she loves playing the piano, and I’ve just been letting her do her thing. She is on her own journey with it, and I was there when she figured out that if you play the same keys over and over, the same notes come out. Before that, she was just playing around, and she would sometimes fall into something interesting, but there was never anything intentional; she never repeated something. This was the first time she played something and realized she could play it again and again. That’s a big milestone, and I didn’t even think of it as a milestone until I experienced it with her.”

***

Family has always been central to Kamasi Washington’s creative process. His young daughter is not the first close relation to contribute to his music: The saxophonist’s father, Rickey Washington, is a veteran flutist and saxophonist himself who has appeared on some of his son’s recordings and is a member of Kamasi’s touring band. He contributes flute to three tracks on the new album.

“I look at my dad as the master teacher,” the 43-year-old Washington says. “He taught me everything I know, and he opened all the doors; he’s always been someone that I can learn from. When I was a kid, he made the choice not to go on the road, to be closer to home with us. I always wanted him to go and do gigs and play music more and then, when The Epic came out, it happened to be right when he was retiring from teaching. That was random; it wasn’t on purpose. So I was like, ‘Hey, you wanna come on the road with us?’ It’s definitely great to see him spread his wings and make music.”

Several other key players on Fearless Movement aren’t literal family members, but they are part of the aforementioned clique of musicians who have worked together since they were all just starting out. Some have known each other since childhood and, as Washington has emerged as a force during the past decade, have built considerable reputations of their own. Bassist Stephen Bruner, better known as Thundercat, has virtually rewritten the role of the electric bass guitar, much in the way that Jaco Pastorius did in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Ronald Bruner Jr., his brother, and Tony Austin provide most of the drumming. Terrace Martin, who plays alto saxophone, is one of several ace horn players that grace this and other Washington projects. Washington calls Martin—who also works with the saxophonist as well as keyboardist Robert Glasper and DJ/producer 9th Wonder in an ongoing group called Dinner Party—“a mastermind who can change the way we think about how we want to make music.”

The main keyboardists, Cameron Graves on piano and Brandon Coleman on electronic keyboards and synths, are essential as well. “Brandon is a sound wizard,” says Washington, “and Cameron is a monster. When we were kids, if you were practicing even close to as much as Cameron was, you were doing OK. He’s so dedicated.” Of the vocalists, Patrice Quinn, who sings on five tracks here, is the most ubiquitous on Washington’s projects. “When Patrice sings a song,” he says, “it goes from being just a song to being a reality.”

In addition to the regular cast, Fearless Movement features a guest vocal by Parliament-Funkadelic pilot George Clinton on “Get Lit,” a track the octogenarian co-wrote with Washington, Ronald Bruner and Daniel Farris; rapper D Smoke also joins the fun on the that one. Then there’s “Dream State,” featuring a flute spot by André 3000, the Outkast MC who recently released his own album of jazz-informed flute music that took many by surprise.

“When I met André, he asked me to record some stuff for him, some music that he was working on,” Washington says. “He said, ‘Hey, man, if you ever need anything, let me know.’ I said, ‘Well, we are actually recording another album right now.’ So he came to the studio, and he brought this whole arsenal of instruments. We played some tunes and, after about the third one, I said, ‘Man, let’s just create something right now.’ So we just improvised the piece together.”

***

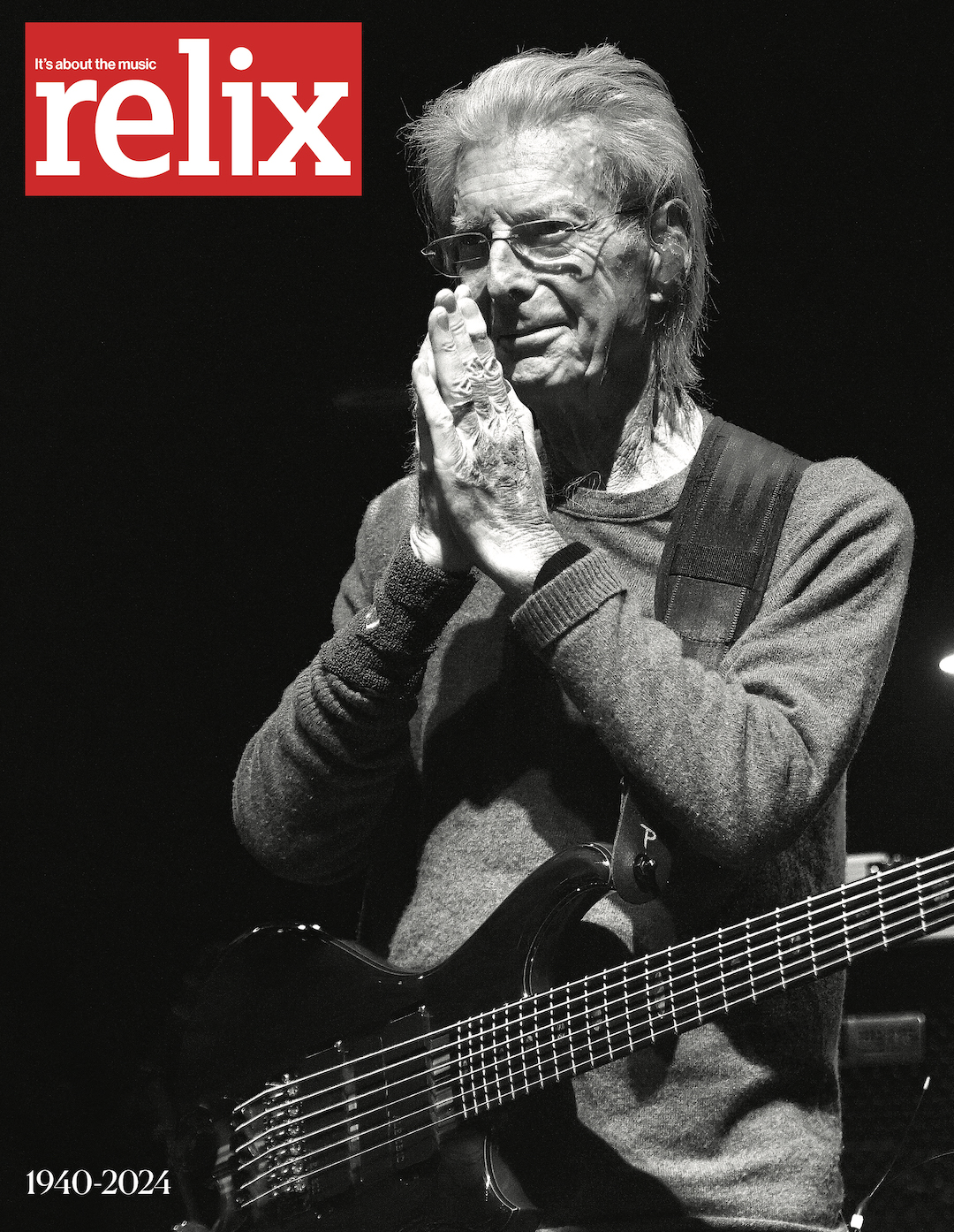

photo: Dean Budnick

***

Washington has described Fearless Movement as dance music but, by that, he doesn’t mean the kind of pounding, thumping, million-beats-per-minute dance music that is dominant in clubs today. The portrayal of Washington’s latest output as dance-friendly goes back to his characterization of it as a representation of the forward motion he’s been experiencing since the birth of his daughter. It’s more akin to modern ballet, as exemplified by the exquisite black-and-white video for “Prologue,” the Piazzolla cover on the album, which, despite its title, closes the collection. Produced and arranged by Washington and Miles Mosley—the double-bassist on most of the album and much of Washington’s previous work—the track is dense and propulsive, a showcase not only for some of Washington’s most intense tenor saxophone work stemming from these sessions but also for Ryan Porter’s stunning trombone and Dontae Winslow’s trumpet. Graves, Austin, Coleman, Ronald Bruner, Mosley, and percussionists Allakoi Peete and Kahlil Cummings also drive the jam.

“Road to Self (KO)” is another piece imbued with that sense of thrust, of bounding ahead. The longest track on the album, clocking in at 13 and a half minutes, it’s multi-layered and multi-textured, taking sharp, unexpected turns, traversing exhilarating highs and lows. Written, produced and arranged solely by Washington, it would serve as the ideal introduction to his music for someone who has never heard him and wants an illustrative tutorial. In some places, it’s reminiscent of a particularly out-there Weather Report tune, which perhaps isn’t that surprising as Washington cites that group’s late Wayne Shorter as one of his prime influences.

“Wayne was my first love as a saxophone player,” he says. “That song, for me, has this ostinato thing that’s happening on the bass, and the chords are moving almost in a way that puts you into a trance. And then the melody feels like this journey, like you’re going through life. You have this mantra, or you have this idea that, at least for me, seems to always be there, but it’s happening in a span that’s always changing.”

Some pundits have also compared the vibe of Fearless Movement to that of the so-called spiritual jazz of the mid-‘60s- ‘80s—meditative, cerebral, often spacey and hypnotic music pioneered by such players as saxophonists John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders and composer-musician Alice Coltrane. One track on Fearless Movement, “Interstellar Peace (The Last Stance),” written by keyboardist Coleman, fits that bill most closely.

“That one’s meant to be like a wormhole or a portal to travel into interstellar space,” Washington says. “That’s something that Sun Ra would do. That music definitely has a warm place in my heart, and that era of music has had a huge impact on me; it’s music that I’ve spent a lot of time listening to, so I’m not surprised that it made its way into what I’m doing. But I’m rarely thinking in those terms,” he adds. “I’m playing the music and trying to hear it for what it is, not usually trying to attach it to anything or anyone in particular. Those types of connections happen on the subconscious level for me, more than the conscious level. But I’m always interested to hear or see what people’s reaction to the music is. Each song has its own vibe.”

One track that definitely keys into nostalgia, however, is the album’s update of the 1986 Zapp hit, “Computer Love.” Washington explains, “Toward the end of the record, I felt like I needed something that had that feel, and I didn’t have a song that I’d written that I wanted to put on it. I was driving home from the studio one day, and ‘Computer Love’ came on the radio. I was like, ‘Oh, man, that would be cool.’ I got home and I worked it out, and then I brought it to the studio the next day. It felt almost like he [Zapp bandleader/producer Roger Troutman, who co-wrote the song] was seeing the future. Then, our version was like the actual reality of what computer love feels like sometimes.”

The ability to grab an idea like that out of thin air and flesh it out in the studio with his friends the next day amplifies why Washington was feeling so constricted during the pandemic lockdown. Patching together an album from separate parts recorded individually by contributors in different home studios and other locations, and then emailed—as is now customary for so many music-makers—and edited into a whole like pieces of a puzzle, is not an option for this artist. He’s a modern guy, but if there’s one old-school thing about the saxophonist, then it’s that he prefers the interactivity that takes place when musicians gather in a physical studio space.

“I [recorded on my own, away from other contributors] for one song, a project I had to do during the pandemic when I wasn’t in the country,” Washington says. “But I didn’t like working like that. To me, there’s some magic that happens when we’re all in a room together that you can’t recreate. You never know when someone’s gonna say one thing or play a chord or play a rhythm that you’ll hear and then the song will reveal itself. And when people aren’t in a room together, you don’t really get that.”

***

Kamasi Washington isn’t much for nostalgia, particularly now, at a time when he is so focused on looking ahead. Still, with the 10th anniversary of The Epic approaching next year, and the birth of his daughter forcing him—as parenthood will do—to put his own life into perspective, he’s sometimes found himself reconsidering the past as well as pondering the future. He speaks of his ascent in the music world with a sense of humble gratitude. The Epic, he recalls, only came about after he’d already paid his dues for years, apprenticing with others who were already established, making home recordings that never found an audience, assembling connections.

“At that point in my life, when we were making The Epic, I felt like I had a group of musicians that had a sound and an approach that was very relevant,” he says. “Even though I was working a lot with some great, legendary artists, [including Snoop Dogg and Kendrick Lamar], and I was doing well as far as playing with other people, my own music was very much in obscurity outside of LA. In LA, I was playing in all types of different places, with all different types of people. I felt like my music had a place in the world, but it didn’t seem like the doors were opening up for me. Me and a lot of the other guys that I grew up playing with, we would hear all these stories of different musicians that came up during my dad’s era, or even before him, and I would ask my dad if he had a record of them, and he’d be like, ‘Nah, they never made a record.’ Honestly, when I was making The Epic, I just wanted to document it. I felt like we were doing something special and something beautiful. I didn’t have a record deal or anything like that, but I felt like I had something to say. I felt like it could do well if it got a chance, but I didn’t know if it would ever get a chance. We recorded The Epic in 2011 and it took a long time for it to come out. By the time it was gonna come out, I was almost thinking we should rerecord it because we had moved on from that music. Heaven and Earth was what we were doing when The Epic came out.”

Although he is deliberate and methodical about fine-tuning his album releases, Washington has filled the in between time by releasing a number of EPs and even recording Becoming, the soundtrack for a 2020 documentary on Michelle Obama. But once he’s finished a project, his thoughts return to what’s ahead.

“I haven’t listened to [the earlier albums] in a while though,” he adds. “I want to grow and find new places and new things because that’s what keeps the music exciting. Just like in life, you don’t want to repeat yourself—what you’re saying, what you’re doing, what you’re thinking. It’s the same thing with the music.