k

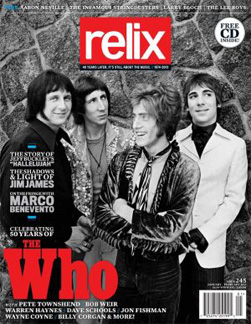

The Who appear on the current cover of Relix in a feature that includes an interview with Pete Townshend as well as many musicians’ memories of the group. Earlier in the month we presented Widespread Panic bassist Dave Schools’ thoughts on John Enwistle. Here is what Phish drummer Jon Fishman has to say about Keith Moon and The Who. It is a expanded version of his comments that appear in the magazine.

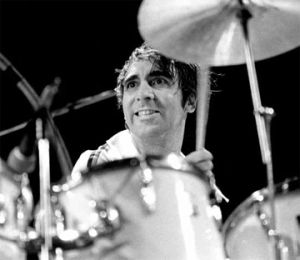

Photo by Neal Preston

Many Moons

Keith Moon is not somebody I studied anything from specifically. With Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and with Zappa’s band – and a lot of the art rock bands like Genesis, Yes, King Crimson and all that – I would learn specific things: specific coordinations, specific grooves and I would learn them beat for beat. And when it came to things like The Beatles and The Stones, I would learn them beat for beat. But from Keith Moon, interestingly when I think about it, I never learned anything of his exactly but his influence was just as great.

The image in my mind that I got when I would listen to The Who, and specifically Keith Moon, was of a guy somehow being able to fall down the stairs in time. It was like someone falling down the stairs with a drum set but landing on the beat. Somehow, this guy would be falling forward and it never seemed like he divided time up in an exact way. It seemed like he was always cramming in the last thoughts in the allowable space provided by the meter of the song.

[Another image I had was of] a guy sliding into home base and barely missing getting tagged out. And a big cloud of dust involved in the process. But getting there, beating the ball and being at the top of the stairs with a whole drum set and just falling down the stairs and landing at the bottom sitting behind the kit with everything where it should be – that is how I felt when I listened to him play. I think I internalized that.

It’s definitely a huge part of what I like about music – that he bent and broke the rules of what was OK and not OK in drumming. It made it more flexible. It made me an understand that when I listen to Zappa that the influences I have from Zappa which – I love all of his drummers just as much – but what I got from them is a very precise ability to divide time and meter, and the beauty of the tension and a release that could be created by being able to precisely go from four in the space of four to five, in the space of four to six, to seven, to eight, to nine. And doing these polyrhythmic groupings within that even meter.

When I listened to [Moon], he was able to create that same sort of effect of tension and release, but in a much spongier way of divided time. It’s like he almost accelerated through drum fills in order to finish on time. If he an idea, he was going to go for it and if he was starting to come up short in – whether or not he was going to get home base in time – he seemed to accelerate through to get to it.

In the Kids Are Alright film, there’s a moment where the interviewer says, “And over here we have the guy that plays the sloppy drums.” And they all laugh and Keith Moon farts. People may called it sloppy but the fact of the matter is – the Buddy Richs of the world have called him an animal, ‘The guy doesn’t know the first about playing drums’ – I would beg to differ. Yeah, he was a crazy man, but I think there was a real strong inner clock and inner pulse that he was aware of and it was just his method.

The rule is that there’s a strong internal pulse; that there’s a groove. You don’t break that rule but there are many different ways to interpret that rule. Keith Moon was certainly one of the really most unique people of all in rock and roll that way.

There’s constant acceleration to his playing. He made it feel like it was always accelerating but [the band’s] time was always really solid. The music didn’t speed up. The tempo of the tune didn’t speed up. But it felt like it was accelerating all the time because he was pushing through the fills to a beat. Every four-beat phrase or every four-eight measure phrase, whatever it was, he’d be pushing through the last…pushing the last juice out of the orange or whatever it was…the last ounces of sound would be squeezed out of the amount of time that was left. And it so it felt like there was an acceleration even though the groove is really solid.

The best example that I can think of that, there’s this moment in the live version of “A Quick One [While He’s Away]” from the Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus that’s in The Kids Are Alright. There’s a moment before they go into the last section, the last movement, of that piece. [sings] It’s right before they get to the “You are forgiven” part…[sings]… there’s this break right before that section where the instruments…it’s almost like the entire band comes crashing into a wall. And there’s actually like a split second of dead silence. The drum solo that happens right there is the quintessential example of what I’m talking about but he did that all the time. That was what he did, that was his playing. It was, “That thing is finishing and that phrase is going to end and Pete Townshend is hitting a big chord there and everything is coming thundering down on that one spot” and he’s still cramming some more [stuff] into the suitcase before he’s got to sit on the damn thing and zip it closed. The last second he would turn it over with security breathing down his neck, “Sir, you gotta move ahead, there are people behind you.” It constantly felt like that.

There’s an elastic urgency here. It’s not simply rubbery. When I think of rubbery, I think of Zigaboo Modeleste. His playing is rubbery; that’s really a flexible funk. There’s a real elasticity to that. With Keith Moon, there was an acceleration. I want to convey that sense of urgency; that acceleration to get that last thought in, that last damn thought in at the last second just before the door closes.

Or [it’s] like there’s a storm coming and you gotta shut the barn door before the storm hits. The wind is howling and you just get that door closed in time and just as you do, there are all these objects that come blowing into the door on the other side. You hear all the rattling and banging of the storm outside.

Learning Quadrophenia

When he had to learn Quadrophenia, that was the one time where I started to actually learn some of the stuff that he did beat for beat. And I found it was incredibly difficult because of that. Because you couldn’t really say, "Oh, well here he plays a roll that’s eighth notes and sixteenth notes and 32nd notes or even triplets; it was like a triplet that piled into some sixteenth notes that actually had a five in a space of four phrase at the very last second.

Page was always a really big Who fan and we were all Who fans. That’s just one of those albums that stands the test of time really well. We all grew up with it and we all went through phases in our years where we were obsessed with it.

All of the albums we’ve done for Halloween met that criteria. Waiting for Columbus was a big one for all of us at one point. Exile at Main Street of course. They all were albums that had been around, stood the test of time, were what we grew up on and were more or less part of our metabolism. I guess, in that sense, it was just a very natural evolution. I can’t remember who specifically brought up Quadrophenia. The way that choosing of the Halloween albums has gone is usually just like there’s a big list.

There’s nothing on Quadrophenia that I couldn’t actually physically play. There were actually couple of things, a couple of moments, on Waiting for Columbus that I could not physically. I couldn’t play some his rolls that fast. I couldn’t actually play some of the stuff. It did teach me how to play some Phish tunes better which is good. Since learning “Tripe Face Boogie” I’ve been working on my left hand shuffle beats a lot.

With Quadrophenia, it was obvious that the guy took a lot of amphetamines. How ever long that album is, it’s straight soloing. The whole time it’s just full throttle.

I was never more tired than getting through that Quadrophenia set. I remember smashing the equipment at the end and having a sledge hammer. I could barely lift the hammer. I was so wiped out. The only other thing that I was that out for was when played from sunset to sunrise at Big Cypress. Something like that. I was a much younger man then, too.

From a technical standpoint, there wasn’t anything I couldn’t play on it in terms of the coordination, but to a large degree, I couldn’t keep up with it. At a certain point, you reach muscle failure. You’re like, “Oh my god, I’m not used to this” It’s like running a marathon like a sprint. It was like, “Wow, this guy really put out a lot of sound and energy.” It’s quite amazing. An incredible amount of energy.

I always thought that Led Zeppelin had the heaviest sound and it seemed like a lot of energy. There’s a lot finesse and precision to those grooves. It’s more like, Robert Plant would say about John Bonham, his whole thing is that his influences were Motown and stuff. And you really feel that and see that when you learn those beats. With Keith Moon, you have no idea where that guy was coming from.

Learning Quadrophenia, you could tell that the guy wasn’t going to live forever. It was definitely, chemically-fueled. There was fuel. There’s no way around that. When you learn to play that music – and you actually try to learn it beat for beat – [you think], “If I was really going to be able to do this for real, I would need the same amphetamines he was eating.” You can feel the sense of burn out. You can almost feel how someone could not go on like that endlessly. Certainly not into middle and old age. There’s no way. It was definitely overdrive the whole time. You can feel it.

The Who: Painting from Negative Space

I think the sheer energy output and release that lineup of Moon, Entwistle, Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey – I don’t think I’ve ever heard anything in rock and roll that was matched in a group setting. Certainly, when I hear Little Richard or certain individuals I think, “Wow, holy smokes.” James Brown or whatever. But the amount of sheer energy that four individuals could churn out, if it were to be translated into voltage, I think The Who have achieved the highest voltage output of any group in the history of rock and roll.

Musically, they’re very interesting in that The Beatles, Stones, Led Zeppelin all had pretty strong and steady bottom ends to their music. The drums and the bass would be these strong foundation. Certainly, Led Zeppelin had the biggest ass in rock and roll. Giant ass and screaming high end but not a whole lot in between. That mid-range was like there was nothing there. It was either shrill or giant.

But The Who, it was almost like reverse. You had this real strong vocal. Daltrey’s voice is a deep, very male voice which is unusual in rock and roll. Overall, I felt like a lot of the best singers sort of had an androgyny to them. I could see why someone like Eddie Vedder would really gravitate toward their music because that plays to his strength as a singer. Other than Jim Morrison and a couple of people in rock and roll, really the Mick Jaggers, David Bowies, Robert Plants, [they] all had these real male and female ranges.

They had a strong male voice that was very sparse in its delivery. [He didn’t] cram a lot of words into short amount of spaces. The same with the guitar. Either long held, big ass chords – big, big chord strikes that rang out – or long, sustained timed notes for the solos. Not a shredder. Pete Townshend was not a Carlos Santana, not a Jimmy Page. Short passages, maybe. But there was none of this [mimics soloing]. There was no room for it because the rhythm section was doing all that.

To me, the most unique thing was that – that was the busiest rhythm section. You had a bass player that was going [mimics busy bass playing] the whole time and you had the drums doing the same thing. On top, you had these big, long sustained textural things. The traditional way of approaching small group rock and roll was turned inside out. They rhythm section was super busy and the traditional lead instruments were very sparse and laid the bed.

I guess you could say, in one way, it was inside out – the rhythm section was busy and the high end and lead instruments weren’t – but you could also say that the bed was Entwistle and Moon created was so busy and it created so much sound and so much noise, that it almost came back around to being a blank slate again for Townshend and Daltrey to draw on top of again. Most painters start with a white canvas and add color. The bass and drums created so much noise that it almost like painting a canvas black first and then taking away. The etchings where people scrape away the color and painting is created out of the negative space.

One of my favorite albums is Loveless by My Bloody Valentine. That album has so many layers of distortion on it that it comes back around to sounding smooth. It doesn’t sound distorted; it sounds like a smooth, ethereal, comforting, warm, enveloping sound. It’s not a harsh, distorted thing. There’s so many layers of harshness that it comes back around to being smooth. I think there are some similarities to The Who in that the business of the rhythm section created a bed that was really solid and strong to almost anything on top of. It didn’t feel like you could do anything too busy.

Their whole approach to a rhythm section was really busy, thick and kinetic – all the time. I can’t think of any other band where that was the whole approach to the rhythm section. Even Hendrix’s band, Mitch Mitchell was a pretty busy drummer but Noel Redding was a very solid, four-on-the-floor type of bass player. Certainly, The Stones, The Beatles – those rhythm sections created simple beds that you could build things on top of logically.

I remember spending an entire year of my life coming home where all I did was put Live at Leeds on. It was that second side, where it goes from one side to another. Nothing ever released that energy level for me. It was such ecstatic release for me to able to listen to that whole side of Live at Leeds. I’d put my headphones on and I’d air-guitar. I’d pretend I was Pete Townshend. I didn’t pretend I was Keith Moon! It was the feeling you’d get, like you just want to scream from top of the mountain kind of feeling.

They always played angry. Pete Townshend always stayed angry and I always felt like he was angry and Keith Moon was always not angry. He was always laughing his ass off. I guess someone had told him or he had gotten word that Phish had covered the Quadrophenia album for Halloween. The feedback that we got from other artists like when we covered Remain in Light or even Waiting for Columbus. I heard Billy Payne said, “Wow, what a nice compliment” even though we screwed up part of it and I felt bad about that and I still feel like apologizing to him. And like, the Talking Heads people, we met David Byrne, and we heard that Tina Weymouth and those guys, there seemed to be a positive vibe of like, “That’s really cool you covered our album and went to the trouble to do a good job with it.”

Someone told me that they read in an interview that Pete Townshend where they’d heard that we – I don’t know if he’s ever heard of Phish or even gives a shit – but that he heard some band in America had covered Quadrophenia and it was big date in America. It sold a lot of tickets and a bunch people went to the show of Quadrophenia and what do you think of this band covering Quadrophenia and his response was negative. Like, “No one plays The Who like The Who! Fuck them!” Which I thought was just right on. Like The Who would just be pissed that we would go out and put a production of Quadrophenia and that his answer to it was like, “Fuck those guys in America, we’re going to do it right.”