Joe Bonamassa: Reading the Tea Leaves

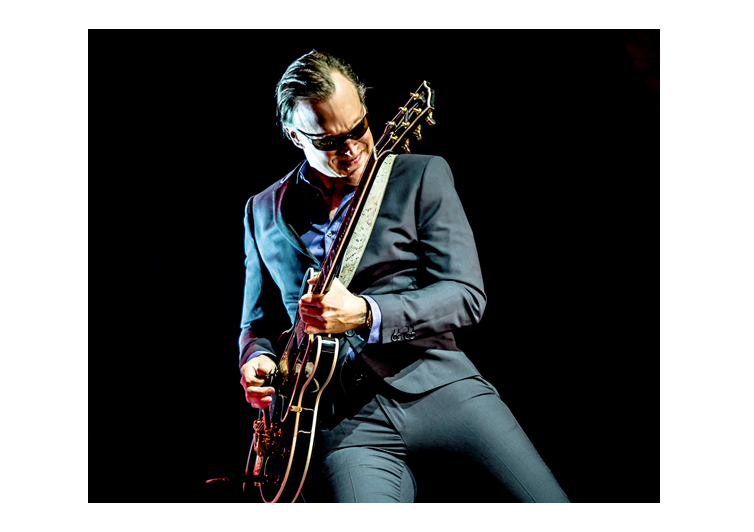

photo credit: Robert Sutton

Joe Bonamassa’s new record, Royal Tea, was not meant to be contained by COVID-19. Released in late October, the 10-song set, like much of Bonamassa’s catalog, is full of blistering, dramatic, blues-influenced numbers begging to be performed in front of an eager live audience. However, with the novel coronavirus pandemic still raging across the United States, the veteran guitarist was faced with a problem he’d never encountered.

“How do you tour a record that is coming out without a tour?” Bonamassa recalls thinking. The answer, for the time being, is livestreams—but Bonamassa was not keen on an intimate backyard show. “Part of the concert experience is going to see a good light show, good sound,” he observes. “I guess I speak for myself, but I’m over the Instagram live concert series and the ‘back porch in my pajamas’ kind of gig. I want my rock stars to be larger than life. That’s what I signed up for.”

Bonamassa practices what he preaches; to promote Royal Tea, he staged a full-production show from the legendary Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, complete with a lightshow, professional sound crew and even an audience—albeit not of real people.

“The weirdest thing about it was that we had 2,000 cardboard cutouts of people printed out and put in seats. So, if you kind of blurred your eyes a little bit, it almost felt like there was a crowd! I looked out there and thought, ‘Oh, I’ve done this gig eight times before at the Ryman.’ It’s always a packed house, and it’s always fun.”

Of course, that blurry-eyed fantasy has its limits. “It all worked until the first song ended,” Bonamassa laments. “It was silent. And we were like, ‘Whoa, man, this is so freaking strange.’ And all you could hear were the footsteps of the crew bringing out the instruments. And you’re like, ‘Wow, that is just a headfuck.’”

Strangeness aside, the show was a success, with the new songs lending themselves well to the historic venue. The Ryman also made the most sense from a COVID-safety and logistics perspective. But a more fitting venue— at least thematically—might have been somewhere across the pond. Royal Tea is drenched in Britishness—and intentionally so. While Bonamassa has long been known for his British blues influences, his new record takes that a step further, in myriad ways. For one, it was recorded at Abbey Road Studios. While that’s a remarkable accomplishment for just about any artist, it holds a special significance for Bonamassa, who is a firm believer in the idea that records can sound like the studios in which they are recorded.

“I still subscribe to the notion of my heroes, like Clapton or The Rolling Stones. They would go to Montserrat or they would go to Muscle Shoals; they would do a record in New York, or whatever,” the guitarist explains. “We’ve done records in Greece, Nashville, LA, Vegas—we’ve done them everywhere. I hear the sound that comes from saying, ‘Pack your suitcase, let’s go live in London for five weeks.’ That was the case here.”

Indeed, Bonamassa’s core personnel for the record—drummer Anton Fig, bassist Michael Rhodes and keyboardist Reese Wynans, as well as his longtime producer Kevin Shirley—all temporarily relocated too. While none of the musicians are native Brits (Rhodes and Wynans are American while Fig and Shirley hail from South Africa), they all quickly immersed themselves in London’s vibe.

“To me, it is a time stamp: ‘This is what it sounded like when we went to London,’” he continues. “There’s a sound to [Abbey Road]; there’s an inspiration that comes through from trying to reconcile the greatness that has come before you, without getting overwhelmed by that. At the end of the day, you end up getting a sound out of it.”

In addition to the location itself, Royal Tea’s British influence draws from the people around Bonamassa. He worked with noteworthy British co-writers such as pianist Jools Holland, former Whitesnake guitarist Bernie Marsden and erstwhile Cream lyricist Pete Brown. “I was really hoping that if I immersed myself in the city of London—and collaborate with British writers like Pete Brown and Bernie Marsden—that I could kind of bring an Anglophile skew to my music,” Bonamassa recalls. “I knew that it worked from the first song that we recorded, which I believe was ‘Royal Tea.’ I went back and I listened to the playback and I said, ‘You know what, this experiment worked.’”

The other cuts from Royal Tea exhibit this sound as well, due both to the recording conditions and the actual writing process. Bonamassa explains: “Coming up with these chord changes, I would ask Bernie, ‘Well, what’s the British translation to this?’ And he would go from these majors to minors, like ‘Why Does It Take So Long to Say Goodbye?’ That, to me, is Bernie Marsden 101—that’s what I hear. I hear the British in those kinds of tunes.”

While Bonamassa is open about his across-the-pond influences, Royal Tea is certainly not an imitation record. Rather it is, in many ways, a distillation of his sound, especially the album’s powerful opening track, “When One Door Opens.”

“If you were to ask, ‘Who is Joe Bonamassa as a blues-rock artist?’ that song has every element,” Bonamassa declares. “It has a chorus, has a melody to it, but it also kicks into a Bolero and a pompous overblown solo. If I needed to write my epitaph, then that is how I would describe myself.”

The nearly eight-minute track kicks off with Bonamassa’s trademark theatricality, including a swelling orchestra, before launching into an undeniably British-blues-tinged electric guitar riff. The song, and the album as a whole, is certainly not understated, and Bonamassa doesn’t disagree.

“I’m not a subtle artist,” he says, bluntly. “After a while, you accept who you are, and I’m the ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ guy. I act like it too. I like it royal, I dress up in a nice suit that I buy at Sears—Sears activewear. It’s not for everybody, but it’s just my taste. I like it big—I’m a big Pink Floyd fan, I’m a big Zeppelin fan. It harkens back to a time when people were striving to make music larger than life.”

Bonamassa also had an equally important emotional inspiration for Royal Tea. “I had a two-year breakup that was kind of off and on—it took a long time to unwind it,” he admits. “I had something to say on this record.

“I think those are the best kind of records, as opposed to those that are like, ‘Well, let’s just make an acclamation of past experiences in theoretical land,’” he continues. “It’s much better when it comes straight from the diary.”

***

For the past 10 years, in addition to a prolific touring and release schedule, Bonamassa has spearheaded Keeping the Blues Alive, a nonprofit the guitarist founded in 2011. The initial mission of the organization, according to its website, was to “conserve the art of music in schools by funding projects, scholarships and grants that preserve music education for the next generation.”

“Up until the pandemic started, all we were doing was giving away money to schools that needed funding for their music programs,” Bonamassa explains. “If you need guitar strings, we’ll buy some from Ernie Ball. If you need saxophone reeds, we’ll call up Selmer. It’s that kind of thing. It just to get music and instruments into kids’ peripheries.”

But, as Bonamassa saw the music industry ravaged by COVID-19, he did some reflecting and came up with a new way to make an impact through Keeping the Blues Alive. In April, he and the foundation announced the Fueling Musicians initiative, a grant program for which artists can apply to get an $1,000 check, along with a $500 gas card.

“We came up with this Fueling Musicians initiative—it was just me sitting on my back deck thinking about when I was a kid living in New York. Our first show was in Tulsa, Okla.,” Bonamassa recalls. “We rented a van and a trailer for the whole tour and we Deadheaded from New York City to Tulsa, which was about 2,100 miles. And I remember having to tell the tour manager we needed to slow down because we were going through too much gasoline.” It was this memory that led to the inclusion of the gas card.

“Keep the gas card in your wallet so that when you do go back out, if you’ve got oneoffs—if you live in Nashville and want to go play Mississippi—the first thousand miles is on me,” Bonamassa explains.

All told, the Fueling Musicians initiative has already gifted over $350,000 and has already given out over 200 grant packages since its inception. “I auctioned off a couple of my prototype signature guitars. We got a bunch of great, generous corporate sponsors, and a bunch of donations from our fans—everything from 10 bucks to five grand,” Bonamassa says. “All that money has gone out as fast as it came in.”

The guitarist is both surprised and grateful to see the program achieve such success. “Hundreds and hundreds of acts signed up for it—and acts that you’ve heard of!” he exclaims. “I was shocked at how much a grant like that was needed. I was like, ‘Man, I’m happy to do it. If that’s my legacy in life—to help other acts in need— then so be it. I’m all about it.”

Bonamassa’s philanthropic efforts related to the novel coronavirus did not stop at Fueling Musicians. He’s also turned his attention to some local, historic venues that are in dire straits. For Halloween, Bonamassa even teamed up with Jimmy Vivino for a livestream benefitting The Baked Potato in Studio City, Calif.

“You’ve got to save those kinds of places,” Bonamassa says. “You can’t not have a Baked Potato or a Troubadour in Los Angeles.

“This is the farm system that everybody relies on when they’re trying to build their act,” he continues. “And they’re legendary clubs that, for all intents and purposes, nobody gives a shit about, as far as state, city and local government. They say, ‘Well, so what if the Troubadour’s not there?’ Really?! You can drive down Santa Monica Boulevard and go, ‘Well, that used to be Doug Weston’s Troubadour where James Taylor, Carole King, Joni Mitchell, the Eagles started and now it’s a Sephora.”’

Bonamassa is dismayed that the government has not recognized the need to support these landmark venues. “There needs to be a national initiative that comes from Washington saying, ‘Listen, we need to make sure Carnegie Hall is still there. We need to make sure that Rose’s in Chicago is still there.’ These are irreplaceable places. We don’t want to just read about it in history books and go, ‘Well, you remember when?’ And unfortunately, it was hard enough to run a cash-in, cashout business—even in the best of times, these venues were teetering. This is just going to take them over the edge.”

That being said, Bonamassa recognizes that, in the current situation, there is a need for artists of his stature to take action. “It’s coming down to where people are like, ‘I’m not going to sit around and watch this go away; we’re going to do something about it.’”

***

Considering the ease with which Bonamassa adapted his charitable mission, it isn’t surprising that he is equally willing to see his sound evolve in the studio. Even after achieving his vision for Royal Tea, he insists the best is yet to come. “I know this is cliché, but I mean it when I say this: I think my best original albums are ahead of me,” the guitarist maintains. “I’m not as overwhelmed by my influences. I’ve collected all the guitars; I’ve fucked with all the gear and got the tones that my heroes had. Now you just go, ‘Will the real Joe Bonamassa please stand up?’

“It’s about refining a sound for yourself, leaving a little bit of a legacy behind and saying, ‘You know what? Maybe I moved the needle for some people, maybe I didn’t. I don’t care, as long as I’m proud of the work,’” he continues. “Every time I put out a new album, I listen back to the old ones and I go, ‘I’m not plateauing, I’m actually addressing things that need to be addressed and hopefully bettering stuff.’” At the same time, Bonamassa is aware of the fickle nature of music consumption. His fans and collaborators may not see the music he creates in the same way he does. But at this point in his over 30-year career, he has come to terms with that. “It’s all subjective,” Bonamassa says with a laugh. “There are songs that I think people are going to freak out over that get responses like, ‘Eh.’ And there is stuff that I didn’t even think we should record that gets a reaction like, ‘I love that.’ So, who am I to know?”