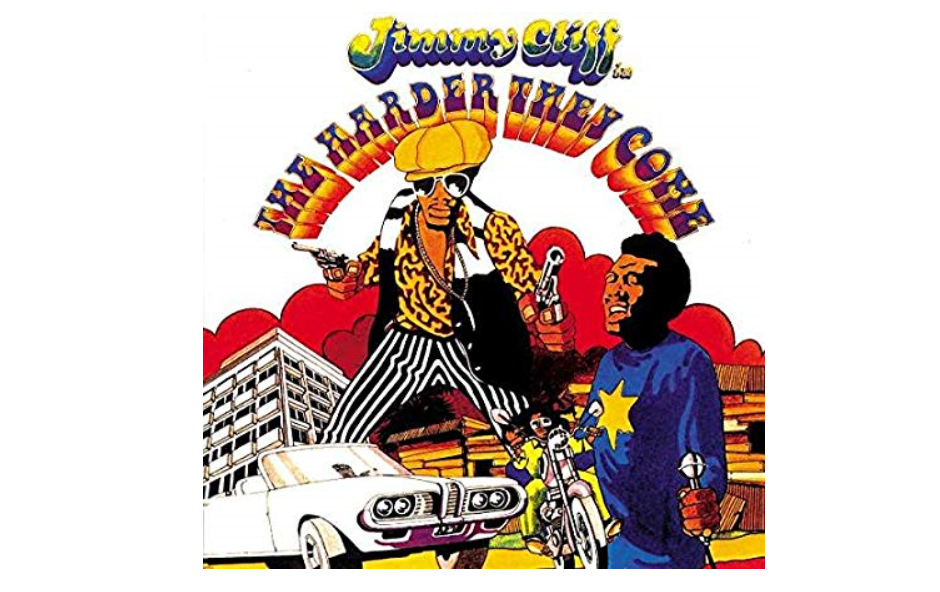

Jimmy Cliff Revisits ‘The Harder They Come’

Jimmy Cliff is regarded without dispute as a true pioneer of Jamaican music—whether ska, soul, roots, or reggae—as well as one of the most revered songwriters of his time. In 1972, Cliff added to his legacy with his cinematic debut, starring in The Harder They Come—the tale of Ivan Martin, a poor Jamaican country boy seeking a better life in the city. A new Collector’s Edition (Shout! Factory) features a 4K scan transferred directly from the 16mm negative of the landmark film as the centerpiece of a three-disc set, now available for the first time on Blu-ray. Additionally included are director Perry Henzell’s long-awaited, reggae-infused, follow-up, No Place Like Home, and a slew of vintage interviews and featurettes, including segments of Cliff’s recording sessions.

While offering his recollections on the film, Cliff also commented on a recent New York Times article reporting a Universal Music warehouse fire that destroyed master recordings and backups of many noteworthy artists; Cliff has been mentioned as one of the artists whose work was lost. “I heard about the fire. I haven’t heard anything before or after (the article) so I assume none of my music was in it. Otherwise, they would have informed me,” says Cliff. As for The Harder They Come, Cliff discusses many of the now-classic film’s themes and lasting impact, its powerful soundtrack, and the one scene in this story of a musician-turned-criminal that scared him the most.

One of the themes of the film is escapism. Your character, Ivan, comes from the country to the city in search of a different life. He reads Playboy and comic books, goes to the movie theater to see shoot-‘em-up Westerns, fixes up a bicycle for rides to the shore, and offers his music to producers and deejays. Everything he does seems motivated by a desire to temporarily or permanently escape his lot in life, either literally or psychologically. Was that a predominant feeling among Jamaicans at the time, to want to escape?

For us at that time in Jamaica one of the ways to escape was through music. The other one was sports. But, music is the one that you can make some money; to make a living. There wasn’t much money in sports unless you got really big. At that time, the sport was cricket, but you had to be really good to make any money from it. For football, or soccer as you call it in America, you would need to get called to England to make it. So, really, to escape, it was music.

Eventually circumstances lead Ivan to crime. Do you see the film as a cautionary tale?

I don’t know if it was cautionary. If it was cautionary, it was (the depiction of) the producer who offered me little or nothing (for my music). The producer did the most atrocious things. Why didn’t he get criminalized for doing that? In the categories (of people) in Jamaica, it was lower, middle, and upper class. Maybe that’s (true) all over of the world, I guess. When you are born into the lower class, if it’s not music, well, you have to sell some ganja. Those were, like, the only two money-making things.

Would you say the film is also a commentary of the oppression of people in Jamaica through economic and social systems?

In the United States, you’ve got (systems). In the UK. In France, where I used to live. All over the world. If you notice, the movie was kind of made in documentary form. Perry (Henzell) was just depicting what he saw going on in Jamaica.

Did you offer any input into the script, based on your personal and professional experiences?

I did. My question all along to Perry when making the film was, Why does my character have to die? Why doesn’t the record producer die? He kept saying, ‘Crime doesn’t pay.’ So all through the movie we had a little conflict about that. Perry was an intelligent man. He would tell us the scene we’d be shooting tomorrow, but when we’d get there he’d say, ‘You know what, Jimmy, forget about what I wrote. How would you do this?’ I’d just go back to some of my experiences living in the ghetto. I understood the behavior- how a bad man would live- because I knew it very well. I put myself in the place of the bad men I knew.

You were filming on location in the ghetto at a time of political and social unrest in Jamaica. Did you ever worry for your safety or were you more concerned with depicting the ghetto accurately so that people could see how rough it really was?

The latter of what you say. For one thing, they’d never seen a Jamaican movie being made in the ghetto, in that area. And I was Jimmy Cliff. I was making a movie, and they thought, ‘He’s one of us. It’s alright.’ The only part of the movie when I was scared was when I was swimming to catch the ship at the end; the ship that was supposed to be going to Cuba. Sharks followed those ships because they would throw old meat off of them. If you look, you can see in my eyes, or my motions, I was scared. I’m a good swimmer, so I did it, but in one take. I’m not doing it twice. One and I was done.

Were you ever concerned with what the perception of Jamaica would be after the film came out?

That’s another question I had: What about those who come to Jamaica for sea and sun? That’s how we get to putting in the scene with the big hotel, and I drove the car on the golf course. We needed to show that other side of Jamaica that was in Kingston.

I think about a movie like Hustle and Flow, and how it seems like a direct descendant of The Harder They Come.

In America, or in England, we see that same kind of character- I don’t want to call out names- but (we see it) in rappers; like you said, in Hustle and Flow. Another movie (example) is Scarface. It’s the same character (as Ivan). Our film had an impact not only for music, but in Hollywood.

Did you have any sense of the impact it might have when you made it?

Not at all did I have that sense. At the time I didn’t even want to do the movie. I was a big star in Europe. I could make a lot of money. I had hits through the charts: “Wonderful World Beautiful People;” “Wild World;” “Vietnam.” Perry said to me- and this is the line that got me to do the film,- ‘I think you’re a better actor than singer.’ I’ve always thought that of myself, even today. First thing in school that I wanted to do was act. I lit up when plays came around for me to do; to recite a poem; to become someone other than myself; anything. I recognize that I have a good voice, but I always loved acting.

How did you prepare for the film? Did you take any lessons or just rely on your experiences as a youth?

Just my love for acting. Okay, showtime! It’s natural for me. No lessons; just doing what I always wanted to do. (From making this film) I know Hollywood. I know producers. You have to play the game.

The soundtrack is just as notable as the film- in some ways, maybe more- for introducing reggae music to an international audience. How much of the music did you write specifically for the movie?

I wrote only one song for the movie, which is the title song. The other song I wrote during the movie, which was “Sitting in Limbo.” I’ll give you a little history. We were filming with the working title of Hard Road to Travel. That’s another song of mine. My character, Ivan, was (essentially) saying the harder they come, the harder they fall. A light went off in my head. I got an idea, and that same night I wrote the song. I played it to Perry the next day and he said, ‘Wow! That’s it.’ He wanted it raw like that.

That scene when you are recording the title song looks and sounds like it was a live performance in the studio. Was it?

Absolutely. He got it raw. Like the rest of the film. He said, ‘I don’t want actors. I want real people.’

There is a great scene during a church service led by an older pastor in which the choir is singing and there is an electric guitar playing. It’s almost like a rock-and-roll gospel. Was this typical of a church service in Jamaica?

Good question. The older pastor was a real pastor. So that was a real scene with him in his church; that’s what he does normally. The other pastor wasn’t a real pastor. He was a dentist. Perry liked him because of the tone of his voice.

In one of the bonus segments, Perry Henzell talks about a possible sequel, saying that Ivan survives the gun battle. What do you think of that idea?

For me, he survived; always in my mind. The idea of doing a part-two was my idea. I never wanted to see that character die, like most who watched (didn’t). You see him get shot down, but you never see him buried. So, we don’t know what happened. I know a friend of mine in Jamaica who took five or six bullets, went to the hospital, broke out, went into the country, got out a hot knife, and pulled every bullet out of him. So, I thought Pedro (Ivan’s friend) could have picked him up and gone to a bush doctor, a medicine man, and medicine him up.

What should audiences today take away from the film?

We spoke about classes earlier. The movie wasn’t only about class. It was also a subtle comment about race. My record producer (in the film) was Chinese, and the other producer was what we call a brown-skinned Jamaican. Jamaica categorizes that way, almost like apartheid: If you’re black, stay back; If you’re brown, stick around; If you are white, you’re alright. There’s a lot of talk in America today about racism. The dirty head of racism has risen up from the crypt. I want to comment on that. When you get to the finish line, we all have to leave our physical body behind. No one wins the race in racism.