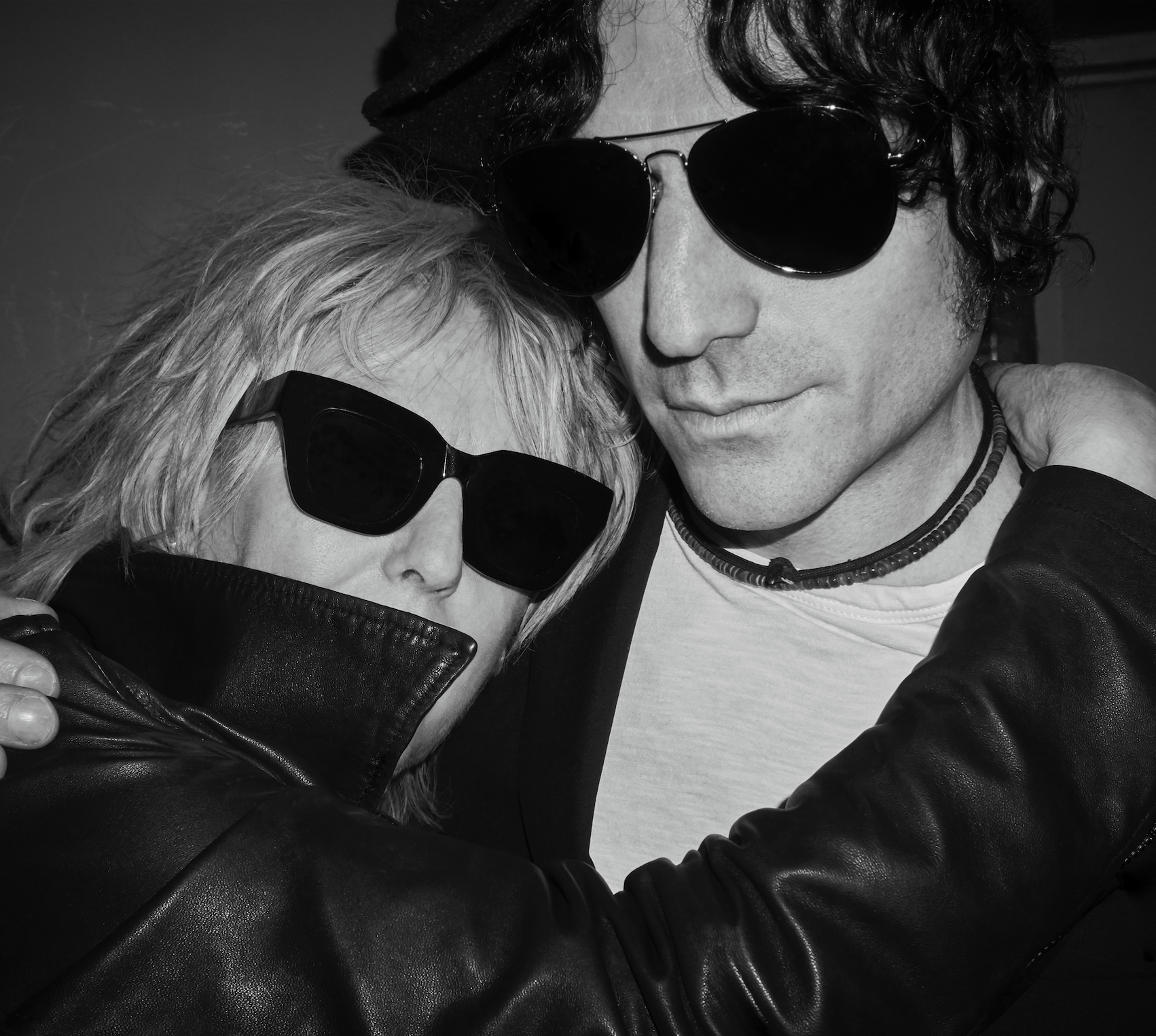

Jesse Malin and Lucinda Williams: Rock and Roll Exorcism

While still doing his part to keep the old, weird New York alive, Jesse Malin looks beyond the East Village on his first album in four years, with the help of Lucinda Williams.

On his third solo album, 2007’s Glitter in the Gutter, singer-songwriter Jesse Malin paid tribute to a friend and fellow tunesmith with a song he called “Lucinda.” It took another dozen years, but Malin and that song’s inspiration, Lucinda Williams, have finally found the time to collaborate on a full-length project. Sunset Kids, Malin’s recently released album on Little Steven Van Zandt’s Wicked Cool label, was co-produced by Williams and her husband, Tom Overby, and it’s easily the most potent collection of Malin music since that earlier breakthrough set.

Sunset Kids arrives a full four years after New York Before the War and Outsiders, the pair of albums Malin released during a particularly prolific period in 2015, and three since Nothing Is Anywhere, his 2016 reunion effort with D Generation, the glampunk band he co-founded in 1991. He hadn’t planned on taking this long to make a follow-up solo recording, but life, as it often does, had other plans for him. One after the other, Malin lost important people in his life, including his father, Paul; his West Coast engineer, David Bianco; former bandmate Todd Youth and others. “When you’re hit with all these heavy things, you either get beaten down or you find a way to jump back,” Malin says. He weathered the losses and chose the latter path.

“When there are hardships, I look to life and I look to music and say, ‘Let’s make the best of it and try to find a way to smile through it a little bit because there’s a lot of dark shit.’ It reminded me of when I made my first solo album and I came out of being in bands,” he adds. “As scary as it was, there was something liberating about it. This batch of songs started to pour out.”

Williams was an obvious choice as producer yet, at the same time, she wasn’t. Malin was born and raised in the New York City borough of Queens and quickly gravitated toward punk and, later, what’s now called Americana. Williams, more than a dozen years his senior, was born in Lake Charles, La., and grew up largely in Arkansas before embarking on a career that has landed her three Grammy wins and another dozen nominations.

Malin recalls first hearing Williams around 20 years ago on a duet she did with Steve Earle, and while neither of them quite remembers where or when they first met—it may have been at a Charlie Watts jazz concert at New York’s Blue Note—at some point, they came into each other’s orbit and a friendship ensued. As Malin began gathering songs for what would eventually become Sunset Kids, the notion of working together popped into his head.

“My manager would come to my house every couple of weeks and say, ‘What do you got?’ and we’d sit around my kitchen table,” he says. “Then, once he felt like we had a good amount of songs, he said, ‘Think about producers.’ That same week, Lucinda Williams had invited me to come out to LA to see her open for what turned out to be Tom Petty’s final concert at the Hollywood Bowl. I said to my manager, ‘What do you think of Lucinda Williams? She’s somebody I really admire and look up to, and it might be an interesting thing.’”

“It just felt real natural,” Williams says. “Tom [Overby] and I had been working in LA with David Bianco, at his studio, and Jesse really liked the sounds we were getting on my albums that I was doing with David. Jesse said, ‘Do you guys want to help me do my next album?’ We said, ‘Yeah, we’d love to.’ But it wasn’t like this out-of-the-blue thing; it happened organically.”

“As people, we’re different,” says Malin about Williams. “We come from such different places. We’ve met up on the road a lot and, if we are in the same town, we’ll go out and listen to music. And Tom is a really great guy. He’s a real fan and a deep listener of music and he had a lot of input in the record.”

Williams’ involvement wasn’t limited to sitting behind the board. She co-wrote two of the album’s key songs, the harmony-rich “Room 13” and the swampy rocker “Dead On,” and contributes vocals to those two as well as “Shane,” the album’s richest ballad. She also offered some sage advice on the lyrical content of the songs, which vary dramatically in style.

“He writes like crazy; he’s so prolific,” Williams says. “He would bring a song to me and have the melody and the structure of the song. He’d have a whole bunch of lyrics and a refrain. He brought ‘Room 13’ to me and said, ‘I’ve got all these lyrics. Can you help me go through and kind of narrow it down?’ So I asked him: ‘What are you trying to say in the song, exactly?’ I wanted to wrap my head around it and get inside of it. We’d go back and forth.”

“She’d be talking about this line or that line,” recalls Malin about the shaping of that same track, “and the next day, she took my six verses and said, ‘These are the three you should use.’ There’s something really open about sitting around with an acoustic guitar and a drink and just going through your stuff. But I was nervous. Even though she’s my friend, I was like, ‘Whoa, the body of work she has.’ But when you have somebody like that it makes you want to do better.”

Once they settled down to actually record, “There were different things going on in different studios,” says Williams. “He was still finishing songs and writing new songs as we were recording.” Most of the music was cut live in the studio, with some overdubbing. Several of Malin’s pals, including Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong and singer-songwriter Joseph Arthur, lent a hand with vocal or instrumental parts.

“With her instinct—from being around music or just having that kind of deep soul or some kind of Southern thing—we’d go in and record a song and do three takes,” says Malin. “We’d record to analog tape. Then we would listen and see if we nailed it, and if she was dancing and grooving her hips and moving, then we knew we had a take.” They recorded about 25 songs in all, with 14 finding their way on to the finished album.

“I know I was involved in the album, but Tom and I think this is the best album he’s made,” says Williams.

***

Growing up in Queens, Jesse Malin was all of 10 when he made his first public appearance with a band, performing Kiss’ “Rock and Roll All Nite” at his public school—“I spit ketchup for blood,” he remembers with a laugh. He was a member of the Kiss Army in his teens but eventually graduated to punk, forming a band called Heart Attack—all of whose members were under 16—only to be told that punk had already peaked. “We went to an audition night at CBGB and they told us that we missed it all. Bad Brains had broken up, The Ramones were going power-pop, Blondie [was going] disco. They said, ‘Try something new like rockabilly or New Romantics.’ I said, ‘I’m not dressing up like a pirate.’”

He soon discovered that the genre wasn’t dead. It had simply sped up, grown more outspoken and morphed into hardcore, with bands like the Dead Kennedys, Black Flag and the Circle Jerks taking the music to the next level. Heart Attack stayed together for four years, after which Malin founded the band Hope, which carried on until 1989.

But it wasn’t until he joined D Generation that Malin truly became a force to be reckoned with. The band not only opened shows for Kiss but also those other Queens natives, The Ramones (Joey Ramone became a close friend). They released three fulllength albums, an EP and numerous singles during their initial eight-year run. It was while making their self-titled debut in 1994 that Malin first connected with Bianco, who produced and engineered it. (The second album, No Lunch, was produced by The Cars’ Ric Ocasek, and the third, Through the Darkness, was produced by David Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti.)

“We wanted to make D Generation into a band that we felt we missed; we felt music had become really safe and funky, with people dressed up like they were farmers from Seattle with no style. We wanted to be in a band that was like a gang,” Malin says. The band was respected but never did cut through commercially. “The people that liked us loved us, but we became more of a cult thing and an artist thing. We had a few bad breaks, but also internally it was so intense. It could be like a five-headed love affair or a five-headed war.”

Malin eventually started growing creatively restless. And punk was also moving in a direction he wasn’t entirely comfortable with. “People thought punk was about swastikas and fascism until the Dead Kennedys said, ‘Nazi punks fuck off.’ Sometimes people misunderstand things,” he says.

After the demise of D Generation, Malin cut an album with a band called Bellvue, To Be Somebody, before making the difficult decision to go the solo troubadour route. “It was kind of nervewracking to call it Jesse Malin,” he says. “I was used to hiding behind four other people and writing for four or five other people. But I think there’s a real connection between punk-rock and folk, from Woody Guthrie to The Clash to Bob Dylan to Crass or the Dead Kennedys. It’s about a message and a couple of chords and an attitude. A lot of my friends that heard me do louder stuff would be kind of surprised when I first did more acoustic-based music. I had people going, ‘What the hell?’ But my real friends knew that I had liked Jim Croce and Elton John since I was eight, and Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen since I was 15. I like songs, whatever they are—the craft.”

His highly regarded solo debut, 2002’s The Fine Art of Self Destruction, was produced by D Generation fan Ryan Adams, whom he’d met in 1996. “It was a very personal first record,” Malin says. He followed it with The Heat (2004) and then Glitter in the Gutter, which featured a guest vocal by none other than Bruce Springsteen, who took note of Malin’s debut.

“I got into Bruce Springsteen late,” he says. “In the ‘80s, I got into Nebraska, and I was like, ‘This guy’s a millionaire and he’s speaking the truth. It’s real and it’s dark and it’s about people on the street, and it’s believable and it’s haunting and it’s so good. And it’s just him alone.’” Springsteen invited Malin to do some holiday shows with him and agreed to lend backing vocals to Malin’s track “Broken Radio.”

From there, Malin’s next move was an all-covers set, On Your Sleeve, featuring favorite tunes by classic rockers like Lou Reed, The Clash, The Rolling Stones, Elton John and Paul Simon, and a live album, Mercury Retrograde. His next full studio album, Love It to Life, arrived in 2010; that same year, he and the members of Green Day killed time with a short-lived band they called Rodeo Queens, releasing one song, “Depression Times.” His five-year break between solo albums was alleviated when a reunited D Generation released their first new album in 17 years. That band also embarked on a well-received tour with stops in London and the U.S., among them a couple of shows opening for Guns N’ Roses. One observer of the tour was Lucinda Williams, who had never seen D Generation during their heyday.

“It was a whole different side of Jesse,” Williams says, “and he was amazing. He had his shirt off, like Iggy Pop, and his microphone cord was long enough that he was able to go all the way to the bar from the stage and drink a shot of tequila and still make it back to the stage. He was great.”

***

Now 51, Jesse Malin still lives in Manhattan’s East Village. “I tried living in Los Angeles but, if you walk in LA, they think you’re a male prostitute,” he says. These days, he can often be found, wearing his trademark suspenders and newsboy cap, at one of the bars or clubs he owns a stake in. “We try to keep a little bit of old New York, New York going somehow,” he says about the establishments, which include popular destinations like Bowery Electric, Lola, Niagara and Cabin Down Below. “Going back to Queens and Brooklyn and places that I tried desperately to get out of, it’s strange to me that there’s now art galleries and gluten-free donuts. But I like that stuff, too. I just love making music and talking about music, then having a few drinks and talking even more.”

As Sunset Kids (titled after a children’s shop in LA—he liked the name, which nodded to his recent losses and nocturnal nature) began making its way out to fans, Malin was looking beyond his own neighborhood, though. “We’re going to do a lot of touring behind this record,” he says. “It’s a privilege to play live after you’ve worked on a record; it’s an exorcism for me to get up there each night over some dirty microphone and spit out whatever it is. So I’ll be doing a bunch of touring around the world—Europe and Japan and the States—and then another record. I want to do something pretty quiet next time and really keep it intimate. And then I want to do a very physical record— something that can be played live. I want to make something that I can move my body to and that’s just completely fun and rhythmic but still aggressive. That’s what I’m thinking now. In between, as Warren Zevon said, I just want to enjoy every sandwich.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more subscribe below.