Jerry Joseph: I’m F***ing Happy

Jerry Joseph can’t sit still. He’s perched at the bottom of a flight of stairs that lead gradually up to an ancient building that once housed a public library, bouncing from foot to foot, similar to the way he does onstage, with a cup of hot black coffee in one hand and a lit cigarette in the other.

In the small Northern California town of Petaluma, Joseph is discussing the past, which inevitably leads to talk of his junkie years (1980s and early ‘90s). But the Jerry Joseph story is no longer about recovering from addiction, that story is so 15 years ago.

“Everybody’s got that stupid fucking story,” says Joseph. “The interesting part about me – I think – is that there’s no ‘and then he got the gold record and we’re interviewing him in his new Ferrari.’ That’s not the story. The uncomfortable story is, why am I still doing it? Because I’m not making any money; I mean, I make a living, but it’s a pretty high toll at 50 years old. And when did not doing this for a living become non-negotiable?”

The simple answer is that this is all he’s ever known. Joseph started playing guitar at six, was in his first band by 11 and started getting paid for it at 15. Though he was a smart, maybe even gifted child, the only thing other than music that he showed any interest in was getting into trouble. Born in Los Angeles and raised in San Diego and his parents shipped him off to New Zealand to boarding school after he failed out of the ninth grade. There, he spent more time in a motorcycle gang than in school. He eventually earned the equivalent of a GED in a lockdown facility.

After what he calls his “juvenile incarceration days,” Joseph was deported from New Zealand and landed in the Northern California hippie enclave Humboldt County, where his family has deep fifth generation roots, and eventually in Logan, Utah where, in 1982, he started the reggae-meets-Grateful Dead-meets-New York Dolls band Little Women. By all accounts, the group should have been huge. They were on the brink but poor business decisions and an increasingly unsustainable drug habit snuffed out Joseph’s first brush with the big time.

The more accurate answer as to why Jerry Joseph still makes music is that he’s really good at it. Success has evaded him, both in the press and financially, and this may add to his poor self image and lack of confidence, but those who do “get” Joseph don’t just dig his music – they believe in it.

“I don’t have a shed full of people [at my shows],” he says. “I wish I did, but the people that do like my music tend to bury their dead to it, or get married to it – these quintessential moments of their lives.”

“He is unparalleled as a songwriter,” says Widespread Panic bassist and frequent Joseph collaborator Dave Schools. “I’m sure there are people who have written as many songs as he has, and maybe even have a litany of hits to their credit, but I’m not interested in them. I’m interested in Jerry because it’s pure. It’s as pure as it gets and there aren’t any filters.”

Schools and Joseph have been friends for more than 20 years, ever since Little Women brought Panic west of the Rockies for the first time as an opening act in 1990. The two have worked together in different capacities ever since, most notably in the jam-rock super group Stockholm Syndrome that they co-founded in 2004, which also features guitarist Eric McFadden, drummer Wally Ingram and Gov’t Mule keyboardist Danny Louis.

“I think what Jerry has in spades is this real honesty,” says Schools, who understands the complex, unpredictable nature of the singer better than most. “Sometimes it’s fucking brutal. It can get bloody onstage with Jerry, especially with The Jackmormons – it can just be an absolute emotional slaughterhouse up there. But people need that. It may turn some people off; they may go, ‘That was way too much to take.’ But it’s unadulterated and it’s not sanitized for your protection, and to me, that’s why I go see live performances of any kind.”

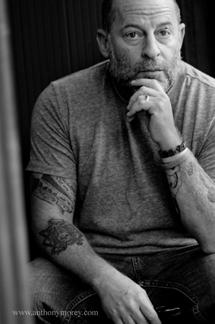

Photo by Tony Morey

Joseph has been laying down this type of cathartic, divisive rock show for the past 17 years with his power trio Jerry Joseph & The Jackmormons. Coming out of a hippie reggae band and heroin haze, Joseph’s first move after Little Women was to hire punk rock/rockabilly bassist JR Ruppel, who didn’t even know who Bob Weir was, let alone had any interest in jamming on Dead songs. Using Bob Mould and Sugar as a template and playing loud, angry music, Joseph says that he lost just about every fan he had over the next year.

“[The Jackmormons] were too aggressive for the traditional jamband scene, at least for as long as it was still called ‘jambands,’” says Joseph. "And because of the association with jambands [specifically Widespread Panic who was covering Joseph staples “Chainsaw City,” “Climb To Safety” and “North” to increasingly large crowds], we were never going to be able to play with Dinosaur Jr. – even though we’d walk out there and for 35 minutes and hold it as fucking tough as a band like Dinosaur Jr. without blinking. But we also have pretty quiet songs and R&B stuff and a shit ton of country stuff."

It wasn’t just the association with jambands that kept The Jackmormons from playing with Dinosaur Jr. or, say, Rage Against the Machine whose politics and agro-rock Joseph could certainly relate to. It was, as he points out, the R&B and country stuff, as well as the Salt-n-Pepa “Lets Talk About Sex” rap that frequently occurs in “Savage Garden,” the reggae inflections, the pop hooks and the 15-minute (highly underrated) guitar jams.

The truth is, whether the scene embraced Ruppel, Joseph and drummer Steve Drizos or not, The Jackmormons are a prototypical jamband – one of the heaviest ever, but a jamband nonetheless. Featuring a marathon two-set show that is wildly different from night to night with a myriad of influences and lots of improvisation, it’s hard to make a case that they belong in any other category. Though as Joseph likes to point out, when he was growing up listening to The Allman Brothers Band, Mahavishnu Orchestra, The Clash, ZZ Top, The Rolling Stones and Steely Dan, it was just called rock and roll.

There are many things that help make Jerry Joseph a unique artist, but what it boils down to, besides the brilliant, prolific songwriting, is the ability to rip himself open in front of an audience, force them to confront his raw inner-workings and, perhaps in the process, confront their own as well.

This often happens in one of his many “raps,” where the tempos stretch out, his eyes fix hard in the distance and his palms start to slam off the side of his sweaty head. When it works, it’s like he’s channeling spirits. It’s what puts him in the argument for one of the great unsung rock and roll frontmen of his generation and it’s what earned him the nickname “The Reverend” by Widespread Panic singer/guitarist John Bell.

“The most powerful thing, if you can’t use the word ‘love,’ is when you say ‘God’ onstage,” remarks Joseph. “Very rarely do I have the balls to do it. I’ve toyed with it before when I’ve had a huge crowd of people and I’m playing some song and I’m like, ‘You’re loved,’ ‘God loves you.’ People are crying – they need it really badly. That’s why U2 is fucking awesome and a lot of the other bands are not so fucking awesome. Because they’re not actually giving people what they fucking need. What they need is to know that they’re not alone and that they’re loved.”

As we head back to the Motel 6 on the other side of town where Joseph is staying, I ask him if that’s what he’s doing onstage: trying to give people what they need and maybe finding a way to not feel so alone himself.

“I’m a 50-year-old, little, bald guy hoping girls will still sorta like me for ten seconds,” he says with a self-deprecating laugh. “But yeah, I’m trying to figure it out sometimes, ‘What do they need?’ Everyone needs to rock out, but that’s not why they’re coming to see me. Nobody is like, ‘Well, what’s going on this weekend? Let’s just go to Jerry because he’s a good time.’”

Having interviewed Joseph more than a dozen times throughout the past decade, traveled through Europe on a tour bus with him and spent many hours in his company stretching from hard drinking nights to sober, Red Bull guzzling ones (he’s been completely sober since Halloween 2008), I can assure you, “a good time” is not the first term that comes to mind. He’s a hot headed, contradictory, opinionated Lebanese-Syrian-Irish-Catholic with a serious Napoleon complex and a tiny fuse. He’s also one of the most intelligent, well- read, loyal, talented, caring and interesting people I’ve ever met.

“People love Jerry,” says Schools. “He can be a very difficult person to be with, but it’s worth it.” In management offices and inner-band circles, this is the knock on Joseph: too difficult. “I always laugh about that,” says Joseph, “I think difficult is in how much you’re getting paid.”

And he’s right, when Van Halen require all brown M&Ms be removed from their candy bowl or rock stars throw tantrums for any number of reasons, it’s deemed “part of the deal,” or perhaps even quaint. There’s simply too much money on the table for managers or venues to complain. But when Joseph, or any of the other musicians out there playing bars and small theaters, blows his top, the profit margins are way too slim (if existent at all) for anyone other than those who genuinely appreciate his music to put up with it.

There’s a strong argument to be made that without the turmoil that Joseph and artists in general create, there wouldn’t be any music. “I’ve got a guy that helps me with management stuff,” explains Joseph. “He says to me the other day, ‘I don’t know if I can deal with all the drama.’ And I’m like, ‘Is it art?’ And he says, ‘Yes, I think at this point, Jerry, you are an artist.’ Then it’s all fucking drama, because I don’t know anybody that makes good art that’s not dramatic on some level.”

Earlier this year, Joseph released his ninth Jackmormons record and 25th record overall (including live efforts and EPs), the double album Happy Book. Inspired by the recent death of his father and birth of his son, the songs swing dramatically from dark to light and at various points, like all his best material, deal with God, sex and drugs on some level.

“I think it’s getting better,” says Joseph about The Jackmormons. “That’s a pretty pretentious thing to say, but I feel like the music is getting better. The writing is getting better to me. And maybe that’s the reward, that because I didn’t get millions of dollars and I don’t have the new Audi commercial, it’s also not sucking more. That might be all there is – that might be the end of the story.”

It’s true that a lack of success and comfort has kept Joseph hungry, forcing him to work hard for every dime and angry enough to continue to create primal, vital rock and roll. And perhaps integrity is all he gets for it, but it’s also possible, as Schools likes to think, that Joseph could triumph in the end like many artists before him have – well after his days on Earth. But Joseph is not ready to give up on the here and now just yet.

“I don’t think I have personally, in my heart of hearts, conceded,” says Joseph. “I tell people, ‘Ya know man, it’s not about being successful anymore,’ I always say that, ‘It’s just about being grateful that I have a job.’ But fuck that. In the back of my head I’m like, ‘Maybe this record is the one.’”

And he’s not the only person who believes fame could arrive at any moment. For as long as Joseph has been in the game, someone has been dangling the carrot of success in front of him. To this day, when he wants to make a record, he doesn’t have to use Kickstarter and if he wants to tour Southeast Asia (as he did last year) or the Middle East (as he will later this year), someone funds it.

There are still people in Joseph’s corner and many of them, including him, thought that Stockholm Syndrome would be the breakthrough. But after two albums, including 2011’s Apollo, which barely made a blip on the music radar even though it was very good, and several tours later, the band fizzled out.

Schools was busy with Panic, Louis with Mule and McFadden and Ingram had a lot going on as well. But Joseph put almost all of his eggs in that basket. He gave the band excellent material, put The Jackmormons on hold and stood on a soapbox screaming, “This isn’t a side project.” But that’s exactly what it turned into and the toll on Joseph was heavy.

“I think everybody thought it was going to be fucking huge,” he says about Stockholm. “Watching that fuck up – I don’t want to admit it – was probably as difficult for me as anything. All this money, all this effort and it’s all gonna go down the fucking tubes. Why?”

It’s a question that Joseph has asked himself countless times: Why? Why not me? But something has been happening during the past few years. Friends of Joseph’s see it in his demeanor and fans hear it on the new album in songs like “Thanks and Praises,” “Mile High, Mile Deep” and “Temple of Love.” Joseph seems to be finding a bit of peace and compassion in his later days. Maybe it’s the Bikram yoga, AA or the bond with his family, but he seems to finally appreciate what he has instead of longing for what he doesn’t.

“I haven’t had to suck anybody’s dick to play my own music and I get paid for it,” he says with a smile. "I’ve got three beautiful children and a baby on the way. I love my wife and she’s gorgeous and seems to love me sometimes. I have some really good friends around the world. I’ve seen a lot of the world and I’m OK. It’s turned out fine – or more than fine.

“Who would have thought that at 50 is when I’d finally figure it out? Life’s short and it doesn’t mean if you say the wrong thing to me I’m not gonna break a fucking bottle over your head, but at the same time, it’s a fucking gift. It’s this big gift and I need to learn to say, ‘thank you’ more.”