Jerry Garcia: The Relix Interview (Part II)

Are there any particular Dead albums that you look back on and are embarrassed by?

Jerry Garcia: All of them! To some extent. Well, there’s moments on all of them that I feel good about and moments that I feel bad about. But by now, I’m so far away from the experience of the albums that I no longer remember what it was that used to annoy me so much about some of the records. Sometimes I have to listen to them again and try to reconstruct it, and then I remember, oh yeah, that’s right, I meant to do another guitar solo on that one. I didn’t mean to keep that one. Things like that. They’re so minor. I never felt that we were a very good recording band. I think we’re just starting to get accomplished at that.

Do you see record making as a necessary evil?

JG: Well, it’s the only other alternative. What do you do with music? You either perform it or you record it. So, there it is, and the fact that there happens to be records and that we happen to be playing music is the only relationship. Otherwise, records are not really an appropriate forum for what we do. For one thing, the time element is not quite right. Our short songs are seven or eight minutes long.

About five years ago, there was some talk about just publicly releasing that huge vault of tapes that the collectors would die to get their hand on. Is that at all feasible as an alternative?

JG: Well, maybe, but the problem is that we don’t have the time to administrate things like that. We have neither the time nor the manpower to do that. So, it’s possible that at some time or another we’ll figure out some way to do that. It doesn’t pay to make real time copies. It takes too long, for one thing. And it wouldn’t work to try to go through and edit things and make discs and pressing out of them, because they would all have to be kind of limited edition things. So we haven’t really figured out a way to handle that, or to deal with it. Nothing that makes any sense. So that remains an archive more than a resource.

How would you compare the San Francisco music scene of today to the scene during its heyday in the late 60’s?

JG: It’s hot. It’s actually hotter now. I think there are more talented groups and better players now then there were back in the old days. It just doesn’t have the big spotlight of publicity or of national attention focused on it. But it’s a very active scene. There’s that little magazine that comes out there, BAM, and there’s a lot of work around the Bay Area. There’s like 40 or 50 clubs that are open seven nights a week. There are some of the smaller record labels that are local to the Bay Area. It’s a pretty vital scene.

Can you see there ever being another Haight type scene?

JG: No, I don’t think so. I think the world is too paranoid for that much looseness to start to crop up anywhere, unless it’s very secretive. But, really, a lot of America is sort of transformed into some sort of extension of that. There are a lot of little rural pockets. Like, we played up in Maine to all these hippies who ran off to live on the land, and have their little truck gardens and go fishing and all that. They’re basically living that other kind of life. We’re sort of the shock troops of that idea. They’re the support, the country cousins or something like that.

When you look back at some of the excesses in which the Dead indulged in the mid-‘70s-the huge sound system, the stadium concerts, the record company you had-what do you think of all that now?

JG: Well, they were good tries. We had to try. And we certainly learned a lot.

Why didn’t that all work out?

JG: For a variety of reasons. We didn’t have the time or the output. For a record company to work, you have to have accounts going with distributors. In other words, they won’t pay you for the records that are coming in. When you send them the new batch of records, they pay you for the ones you already sold. So there’s this long credit overlap. And a lot of times they don’t pay. A lot of times, they burn you. And we got involved with records with uncannily perfect timing, just the year when polyvinyl chloride went up seven million percent and oil shortages started to break in heavy. And that same year was the year we got involved. So all of a sudden here we were having to dicker for virgin vinyl, which there is no more.

Last year, the music business went through a supposed economic slump. How did that affect the Dead?

JG: It didn’t affect us at all. Shit, we’re booming. The rest of the world is going to pieces and we’re doing fine.

Are you influenced by any of the trends that are around? Do you listen to the radio?

JG: Sure. I listen to everything.

Anything particular that’s turned you on lately?

JG: Just the stuff that hit everybody. I like The Wall a lot. Everybody likes that. I like Elvis Costello. I’m a big Elvis Costello fan. I like Warren Zevon a lot. I mean, I’ve heard good stuff from almost everybody, just like I’ve heard bad stuff from almost everybody. I don’t think there’s anybody who’s consistently putting out great stuff, time after time after time. But everybody’s got something to say and there’s moments in all of this that are real excellent. I go for the moments. I keep listening till I hear something that knocks me out. Dire Straits-I love that band. It’s hard not to like that band.

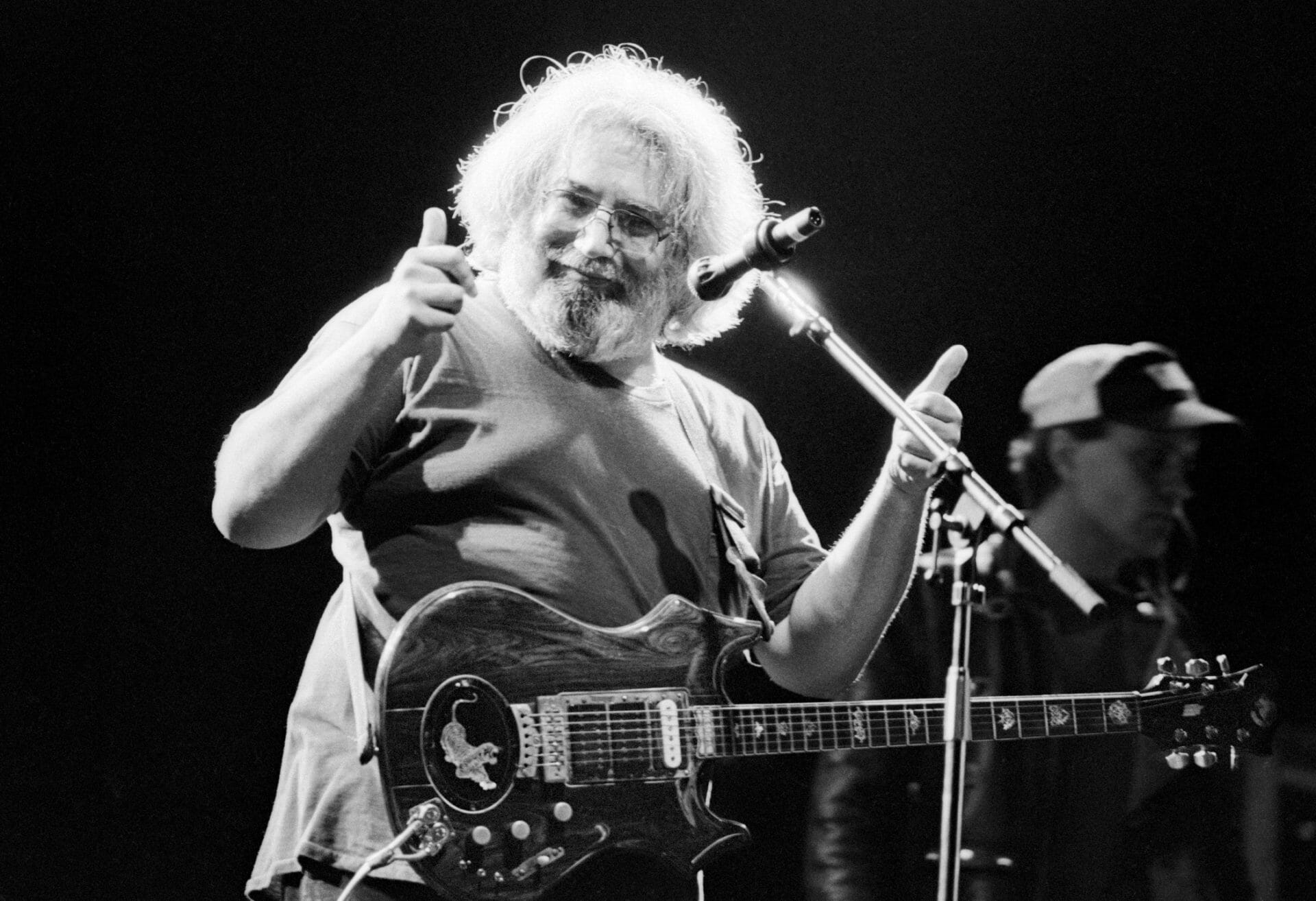

A couple of questions for the musicians reading. What kind of guitar are you using now? I know you’ve used the same one for over a year now.

JG: Yeah, this guitar was built for me by a guy named Doug Irwin, who also built the guitar that I’ve been playing since about ’73. I ordered this guitar from him when he delivered the other guitar. He also built the bass that Phil’s playing now. He’s kind of retired from instrument making. The work he does is so fine and the instruments he makes are so incredible that there’s just no market for them except for a few heavy duty professionals. He’s just got an amazing understanding of wood. But above and beyond that, the reason I’ve gotten guitars from him is because there’s something about the feel of his guitars which is really extraordinary. I’ve played a lot of new guitars by people who are building guitars from scratch, and the thing of knowing about touch is a gift. This guy is one of those guys who’s got the gift, apart from amazing craftsmanship.

What about amps?

JG: The basic pre-amplifier is an old Fender Twin Reverb that I’ve been using since ’67.

Do you use the same equipment on stage and in the studio?

JG: Pretty much. In the studio, I tend to use more of a variety of amps. I have a lot of little old Fender amplifiers. Recording is an illusion. Size and relative volume are an illusion you can create in the studio. An amplifier this big (a foot or two) can sound like a thousand Marshalls. The microphone doesn’t hear the way the ear does. So after recording for this long, I’ve gotten so that I can get what I’m trying to get, in terms of guitar sounds.

Getting to the newest album, Go To Heaven, where did you find Gary Lyons, your producer?

JG: We like his work with Wet Willie and some of the other groups he’s work with. So we invited him out and then we met, we clicked.

A lot of people got worried when they heard you were using the same person who produced Foreigner and Aerosmith. But he didn’t seem to affect the sound in any great way.

JG: No. He understands. He understood what we were getting at musically. I think he’s the best producer we’ve had yet in terms of really having a commitment to the group, getting really into it. He’s not a standoffish guy and he’s not a guy who has a lot of English rock and roll affectations. He’s an easy-going guy.

How would you compare working with him to working with Keith Olsen (Terrapin Station) or (the late) Lowell George (Shakedown Street)?

JG: I think that Keith Olson has a technical upper hand on Gary. But he’s also more…when we went to work with Keith, we moved into his world and did things his way. We did his routine based on the reality of what we were. He made an effort to understand who were as individuals, as a group, how the music was going, and so forth. And then, he put together his approach to how he was going to work with us, based on that. Lowell was real loose, but he was also real busy. He wasn’t around for a lot of the record. The record was basically finished without him. So the production on that was really a three-way job. Lowell was there for the basics, but for the vocals and final overdubs it was really Dan Healy and John Kahn who were more or less functioning in the role of producer.

One thing I noticed is that Lyons really captured the nuances of the band, little percussive things that Mickey (Hart, drummer) does and so forth, which haven’t really been captured on record that well before.

JG: Yeah, that’s true. He did.

I’d like to clear up a historical question that’s often a matter of dissension among Deadheads. Did you do any recording before the Dead, not counting the Warlocks single and the record one which you backed (blues singer) Jon Hendricks? Was there anything before that?

JG: I did some various sessions around San Francisco. Demos and stuff like that.

Anything that was released?

JG: I really don’t know.

Well, here’s why I ask. I heard that you played on the hit single by Bobby Freeman, the original recording of “Do You Want To Dance.” Is that true?

JG: I played with Bobby Freeman, but I’m not sure whether it was released. I played on a demo, but I’m not sure if that’s the one that was released.

That would be the early ‘60s, right?

JG: No, that was the ‘50s! [note: “Do You Want To Dance” was released in April, 1958!]. Sure was.

How has you attitude toward making records changed. Are you more serious about it now?

JG: I sort of went through various cycles. I got to be very involved in knowing the studio. I spent a lot of time learning about it. That’s why I got my own board, my own machines. I function as producer on my own records, more or less. Then I got really bored with it. I think of recording as sort of a necessary evil in a way. I’m looking forward to a time when I can approach it differently, from a point of having more fun, and worrying about it less.

What’s the difference between making a Dead record and doing your solo albums? Are you more at ease during a Dead record because the decisions are group decisions?

JG: Yeah, a Dead record is always a group thing. On my own records, I am making the decisions. So, fundamentally, there are no surprises. I’ve gotten to feel pretty good about both things. But it goes through cycles.

Is the making of a Dead record a democratic process, where everyone has an equal say about what’s going on?

JG: Ha ha ha! Democratic is the wrong word for it. Anarchic is more like it. What it is is that people have ideas and various way of bringing them up. Some people have lots and lots of ideas and then they go through the thing of experimenting with each of the ideas and say, “Is this gonna work with the tune, or this gonna work with the tune? Let me try this, let me try that. Let’s see if this is gonna work.” Others have one idea but they have tremendous conviction about it. So, since the studio offers you that kind of flexibility, we go both ways with that stuff somewhere between those two poles.

Phil Lesh said you’d be the one to answer this. Will there ever be another acoustic Dead set in concert?

JG: Yeah, it’s possible.

In the last few years, the band has been the brunt of a critical backlash. Does it bother you to read someone saying that the Dead have had it, that they’re past the peak?

JG: It doesn’t bother me. I mean, it doesn’t affect us when we get good reviews, either. That isn’t what we’re doing. We’re not fishing for compliments. We’re so used to getting bad reviews on our records that we sort of look for them. The worst of ‘em are more fun than a good review.

I see your crew looks like it’s ready to leave, so how about if we end with a couple of hypothetical situations. First one: if any of the core members of the band, meaning you, Bob, or Phil left, would the band carry on?

JG: No. Well, I don’t know. It’s hard to say.

OK, one last one. In a thousand years, when it’s all gone, what will the music history books say about the Grateful Dead?

JG: Ha! I haven’t the slightest idea!