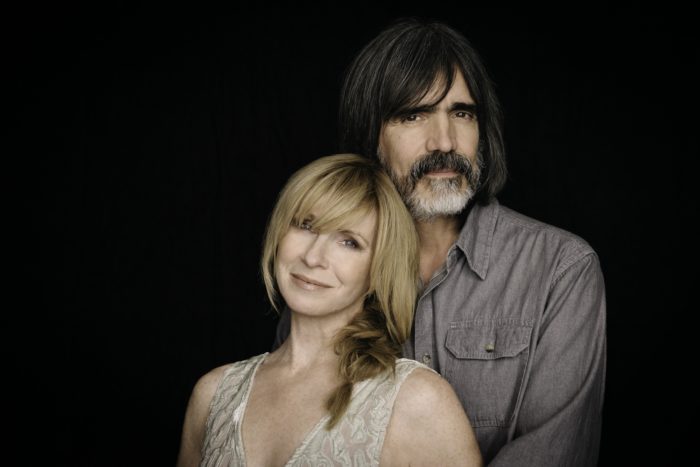

Interview: Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams on Marital Collaboration, Levon Helm and Why ‘It Was The Music’

photo credit: Jacob Blickenstaff

When filmmaker Mark Moskowitz happened upon a performance by Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams at the Ardmore Music Hall in January 2016, he had an epiphany. Moved by the couple’s interplay and sublime musical expressions, he decided the time was right to dig in and direct another feature-length documentary. His initial goal was to explore their personal narrative, as well as the passions of music lovers, in a similar way that he tracked both reclusive author Dow Mossman and the general appeal of literature in his 2003 film, Stone Reader.

After convincing the duo to participate, Moskowitz followed the longtime married couple over the ensuing 15 months as they recorded and released their second studio album, 2017’s Contraband Love. Rather than a two-hour film, Moskowitz ultimately created It Was the Music, a 10-part series that not only chronicles their personal and professional relationship—including work with Bob Dylan, Levon Helm, Phil Lesh, Jackson Browne and Hot Tuna—but raises larger questions about culture and connection. The resulting film is a profound and moving work that’s suffused with the sweet sounds it contemplates, courtesy of Campbell, Williams, Bob Weir, Jorma Kaukonen, Jack Casady, Jerry Douglas, David Bromberg, Jerron “Blind Boy” Paxton and others.

Mark pitched the two of you on It Was the Music while you were seated at a signing table after a show. He formulated it during the course of that performance. Was his vision consistent throughout the process of making the series or did it evolve?

TERESA WILLIAMS: He did stick with his vision, but he’s quick to say that some of the responses he’s getting are unexpected. Throughout the series, I talk about how wonderful it is that Larry and I work together. That’s all good, but I also lay into the fact that my parents are aging and I feel a need to be with them. Mark says that people keep telling him that the series really makes you think about what is really important. He’s asking, “What is the most meaningful thing for you? How do you juggle these things?” There’s a generational side to it, too. He also says—and this is his big summary—that a project ends up telling you what it’s about. You start out with your vision and you do the best you can to work toward that vision but then the project ends up telling you what it’s about when it’s done. I think that’s true.

LARRY CAMPBELL: He originally wanted this to be a two-hour art-house film with a limited theme about music and the communication that happens between a musician and a listener. Then as things went on, he realized that there were other aspects to the story he was telling. Like Teresa said, this project showed him what it wanted to be. And it turned into this 10-part series because he ended up going a lot deeper than he thought he was going to go.

While the exploration of musical reception is interesting, to my mind, the heart of the series is your relationship. The two of you are so honest and the filmmakers capture so many intimate moments. Were you surprised by your portrayal?

TW: I suppose I wasn’t because we were there when they shot it. [Laughs.] However, it’s difficult for me to look at it because I relive the pain of certain moments, like when Larry first showed me this song [“Save Me From Myself”] and I’m weeping. Honestly, I was so exhausted through much of the shooting that I’m weepy in many of the scenes. Then I relive the pain because I remember what was going on in the moment that made me weep. So it’s really hard. If I could have gotten away with it, I wouldn’t have watched it because it’s painful. I feel like we’ve already been there, done that. I don’t want to live through that again.

LC: For me, watching this thing with any kind of objectivity is next to impossible. But when it was all said and done, and I hadn’t seen any rough cuts for a while, I finally watched the final product in its sequence. That’s when I appreciated that Mark has been able to get an extremely honest portrayal of who we are, what we do and what happened through that time. It’s a good record of our relationship and I wasn’t expecting to see so much emphasis on that.

Through your songs and stories, you directly express a range of ideas and emotions about each other, often on a nightly basis. Have you found that to be a blessing, a curse or a bit of both?

TW: Well, I’m so narcissistic that every time I hear a new song that Larry has written, I think, “Oh, he wrote that after the argument we had the other day. I’m so mad that he wrote about it and he got it all wrong.” Then, at some point down the road, he’ll say, “Oh, yeah, that was about my parents.” Meanwhile, this whole time, I’ve been mad about that song.

So it’s both a blessing and a curse. There are times when I’ve said to Larry: “I’m not singing this one. It’s for you to sing.” And then, of course, I do. [Laughs.]

LC: Not many marriages can survive a professional relationship, too. That can be a recipe for disaster. But we sort of hit the gold mine with this. I think it is because of our experiences before we met and got married. We had both been around the block by the time we got together. We both knew who we were and had a good idea of who the other person was. That applies to our ability to sing together, to create together and to communicate intimately—Teresa helps me as an editor with these songs.

TW: We were both, as we say down here, “eat up with music.” We both grew up with it in the household. Somebody in my house was always either making their own music or listening to the radio—even when we were working in the field, my brother would string a radio to his belt, so we’d be hoeing the corn and he would have the radio on. With Larry, it was the same thing; his mother was passionate about music. So that’s been a glue and that’s how we found each other in the middle of Manhattan. It’s like finding a needle in a haystack and, as unexpected as it sounds, it was kind of inevitable at the same time.

LC: We’re both pretty fluent in being able to communicate through music, and we aren’t competitive. We have a professional respect for each other. We could be mad as hell, fighting about the kitchen garbage or something, and then go on stage and still become who we’re supposed to be on that stage. That connection between us has its own space and its own time, and we can easily go to it and treat it with the respect that it deserves.

TW: It’s embarrassing and, at the same time, it’s very real. There’s a scene where we’re rehearsing with the film crew there. They have too many angles for it to be one that we set up and shot ourselves, but the way we’re acting doesn’t feel like they’re present. We’re sitting by the fireplace and we’re rehearsing a new song [“It Ain’t Gonna Be a Good Night”], so I’m not comfortable to begin with. I have my ideas about how I want it to go and he has his firm, fixed ideas of how he wants it to go. And so there’s like a test, and I’m trying not to be angry. But I’m obviously angry that he’s trying to make it be the way he wants, and I say, “I’ll be your puppet singer.” But it’s all out of some passionate feeling about how the music should be.

There are other arguments in there about other things, like moving home and my family and all that because my dad has got Alzheimer’s, which is something we could see coming because it runs in the family. So that’s a whole other kind of argument, but it’s good that there was one in there about the music.

When we did the watch party on FANS, Rosanne [Cash] made me feel better when she said that she understood what I was going through and that she doesn’t like it when her husband, John [Leventhal], tries to dictate what she’s supposed to do vocally.

Moving to your musical accomplishments, there is a moment in the series when Larry describes playing an iconic song onstage with Dylan and allowing himself the luxury of stepping outside himself, ever so briefly, to allow the glory of that moment to sink in. Teresa, have you had a similar experience?

TW: Yes, and it’s one of the favorite moments of my life. My daddy taught me guitar with his old beautiful Gibson and then he presented me with a little guitar on Christmas—I was 10 or 11. He used to do “Long Black Veil” a lot, probably the Johnny Cash version. So I grew up with that. And then when we started working with Levon, I didn’t know those Band records—I led a sheltered life until a certain point and we didn’t have rock-and-roll. I knew “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” but nothing deeper. My brother had their records, but he was younger than me so I had moved out before he really amassed his record collection.

Since Levon wasn’t able to sing all the time, he needed all of us to step up. What Larry and I do now evolved out of that. It was something we’d do for fun down here [in Tennessee] with the locals; then everything kind of got formalized with Levon. Larry and I would sing duets with Levon singing backup for us, which was great. I think Jimmy Vivino suggested that I do “Long Black Veil” and Levon had me relearn it the way The Band did it with the same phrasing and stuff.

So when we did Ramble at the Ryman, I sang “Long Black Veil,” this song Levon had a lot of success with, while he sat there on the drums.

My parents were out in the pews, where they had brought me when I was little—going to Ryman Auditorium was like going to Mecca for us. It was this massive thing.

So I was able to stand there in the moment and go, “This is beautiful. I’m singing this song my dad taught me. He taught me to play guitar. I’m playing on a guitar that Levon gave me and he’s sitting over there on drums. And I’m on stage at the Ryman.” I can’t even tell you how many circles that completed.

Levon had also been an artistic touchstone for me as an actor and as a singer. When I realized that the voice on “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” was the same voice of the actor who played Loretta Lynn’s father in Coal Miner’s Daughter, I thought my head was going to explode. I never dreamed I would meet or work with him. It just blows your mind how these things fall out in the universe.

In a somewhat parallel manner, can you recall the first time that you heard your own music being broadcast?

LC: Back in the ‘70s, I was playing with a band called Cottonmouth. I had just gotten out of high school and the owner of the studio was trying to cultivate the band. That’s a whole book I’ll write someday. We were given free time at Mediasound Studios late at night where we would make these demos on the way toward hopefully making a record. We had a gig at Fordham coming up and I was listening to FUV. They were promoting the gig and they played a cut that we had done in the studio that I didn’t even realize they had access to. That was the first time I heard myself on a radio station that I listened to regularly. FUV played all the greatest music that I was way into. It was a heady moment.

TW: That’s so cool, Larry. I don’t really remember a moment like that.

Can you remember a specific live show you saw that led you to believe you could pursue a career in music?

TW: There wasn’t a major moment like that for me because, growing up, I was always the girl who sang. I was a soloist at church from the age of four. Then I was the girl who sang in my county, at my high school and all that. I sounded like people on the radio so I figured I could do that if I want to. But I was leery of the music business, so I went the theater route as far as school is concerned.

However, I do recall this spark-popping moment at church when I was young. I was communing with the audience and thinking, “This is who I am and this is my life’s calling.” I can remember where I was standing. I was really little.

That’s the whole purpose of what I do now. Standing up there and telling stories is my life’s calling. What’s important is the connection with the audience—that spark you get. For me, it wasn’t about records, it wasn’t about film; it was about that one-on-one with the audience and it still is. That was what Mark was trying to tease out—what is that spark? Of course, the whole world would like to tease that out. It’s ephemeral.

LC: For me, it’s simple. I can’t overstate the significance of this moment, and many people had the same experience. It was Feb. 9, 1964, on The Ed Sullivan Show. When I first saw The Beatles, that was it— I knew. The next day, I woke up and I knew that I was going to do this in some form or fashion, and I’ve never looked back. Every minute of my life from then on has been geared toward making this career happen. It’s really that simple.

After that, growing up in New York, I had the opportunity to see so many great musicians. I saw Hendrix and Cream and Joplin and Moby Grape and the Dead and the Airplane—all these great groups at the Fillmore and other places. And each of those performances was fuel for my engine to make myself do this.

TW: The first time I saw Tina Turner on TV, I was like, “Oh, yeah!”—just the raw energy. It reminded me of those moments at church and communing with the audience. It’s not about the applause; it’s about the exchange of energy that takes place through the emotional connection with the audience.

LC: You can feel them getting it. Even if they’re just sitting there, you can tell when something happens. When you strike a chord with an audience, you can feel them getting it and then it comes back and hits you.

TW: It’s not even conscious. It’s a subliminal thing that Mark was trying to tease out. But we’ll never tease that out. It’s magic. It’s light moving back and forth. It’s quantum physics.

The film triangulates between Woodstock, Manhattan and West Tennessee. Do you feel that each of those regions contributes something different to your musical expressions?

TW: For me, I find that I will have a better show with Larry if I’ve just come back from a couple of weeks in Tennessee. When I come back from Tennessee, my guard is down and my emotions are close to the surface in a good way. It enables me to get out of the way and let the music and feelings flow through me to whatever story the song wants to tell the audience. I try to stay out of the way and let it flow through but, as a biological being, I’m not always successful.

I hate to say this, but my family has been on this farm basically since the government took it from the First Nations. We’ve been here almost 200 years. So that’s really deep. A lot of the people here moved in and never left from that era. They never traveled or went anywhere. So there’s a lot that’s retained, even though some of it was lost with my grandparents’ generation and my parents.

LC: I grew up in Manhattan, so that’s home and it has its own comfort level, which plays into my creative output. But I left New York in the early ‘70s and went to California, Texas and Mississippi before I came back to Manhattan at the end of the ‘70s and began a pretty lucrative and successful career as a New York City studio musician. So when I’m in New York, the professional musician head seems to come in. Woodstock is a place I’ve been coming to, off and on, since then and that’s always been where the creative artist head kind of takes over. I feel like the songs that I’ve written over the past decade or so would never have been written if I hadn’t been in Woodstock. I feel much more capable of being a creative person in Woodstock. In the city, I feel like I’m the professional, competent musician.

Then when I’m in Tennessee with Teresa, and I have the opportunity to play with some of the locals down there, that kicks in this whole other dimension for me. Ever since I started playing music, I was enamored with the honesty of the music that came out of the Southern part of the United States. So it’s really captivating for me to be down there and have the opportunity to play with these local guys, where finesse or technique are secondary to the raw passion that comes out in their playing.

Although you shot It Was the Music a couple of years ago, it was released during the pandemic. How do you feel that the quarantine has impacted the public response to the series and to your roles as musicians?

TW: I think it’s not for nothing that it took a while to figure out how this film would come out. It turned into a series and then they had to figure out how to present it. And I think that you couldn’t have picked a better time for a film that talks about music and what it means to people than during a pandemic when people are isolated.

I just saw something on Saving Country Music. Chris Stapleton talks about being backstage at the Grammys and meeting Katy Perry. They were talking and he said, “You know, we’re just musicians and we’re not all that important.” This was pre-COVID and she said she was offended because music is vitally important, and sometimes a song is the last thing that can pull you out of your depths. He was thinking more practically and she was thinking about the impact of music on your soul. He said that it made him look at things differently. So there’s a reason the series managed to make its way out into the world when it did.

LC: I had COVID early on, in March of last year. It was horrible. It really knocked me down for about six or seven weeks and I wasn’t able to even think about making music during that time. But when I was finally pulling out of it, I had this insatiable appetite to get back to being a musician. That was all I could think about. I felt like I almost had to start from scratch after I had been away from it for so long. And when I was able to start coming back, I had this realization about the importance of musical expression.

I got this app on my phone that allowed me to film myself five different times and become a virtual bluegrass band—I played mandolin, fiddle, banjo, guitar and bass. I did a couple of these fiddle tunes and our manager put them on social media, and the response was incredible. This was only a few months into the pandemic but so many of the comments were from people craving live music again. And, for me, it was essential therapy. It helped me get back to being who I was and, subsequently, it turned out to be good therapy for the people viewing it as well, helping to satisfy their need for live music.

There are so many wonderful musical performances in the series. Thinking back, can you each name a moment that captures the spirit of It Was the Music, or otherwise jumps out at you?

LC: I love the moment with Teresa singing “Sugaree” with Jack Casady, Jorma Kaukonen Justin Guip, Jesse Murphy and me at the Targhee Music Festival. I love the way she sings that song. And the fact that we’re playing a mix of their take and our take of a Grateful Dead tune with Jack and Jorma— who were contemporaries of these guys and come from the same primal ooze—made it a very special performance.

TW: I’ll say my father singing his version of Jimmy Rodgers’ “T for Texas” on July 3 while they’re barbecuing the hog. He was almost gone into Alzheimer’s—he couldn’t do it now—but he even gets in a little yodel. That’s probably the most dear moment for me.