Interview: Jorma Kaukonen

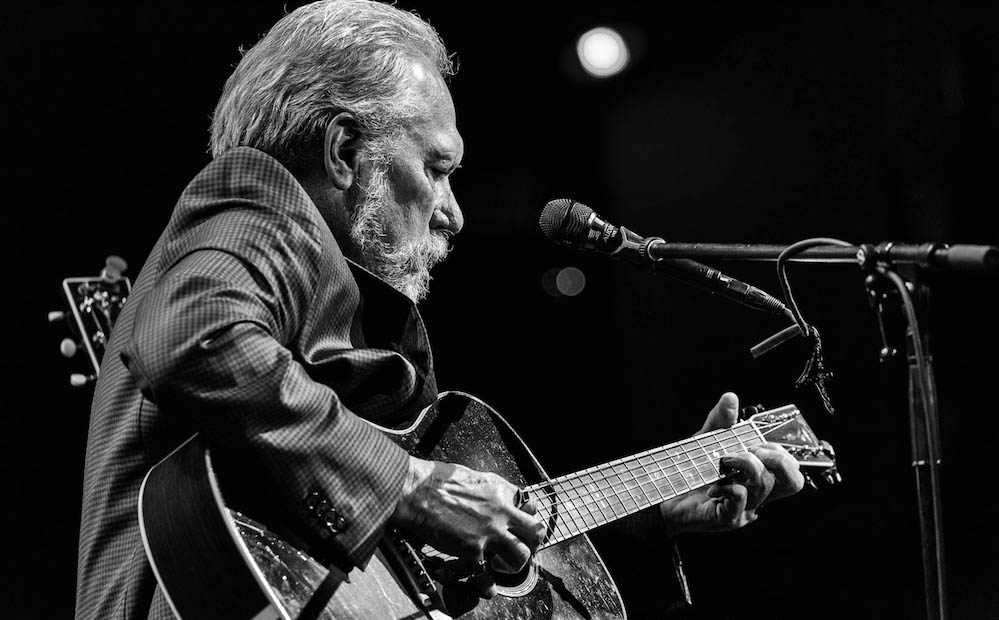

photo by Bill Kelly

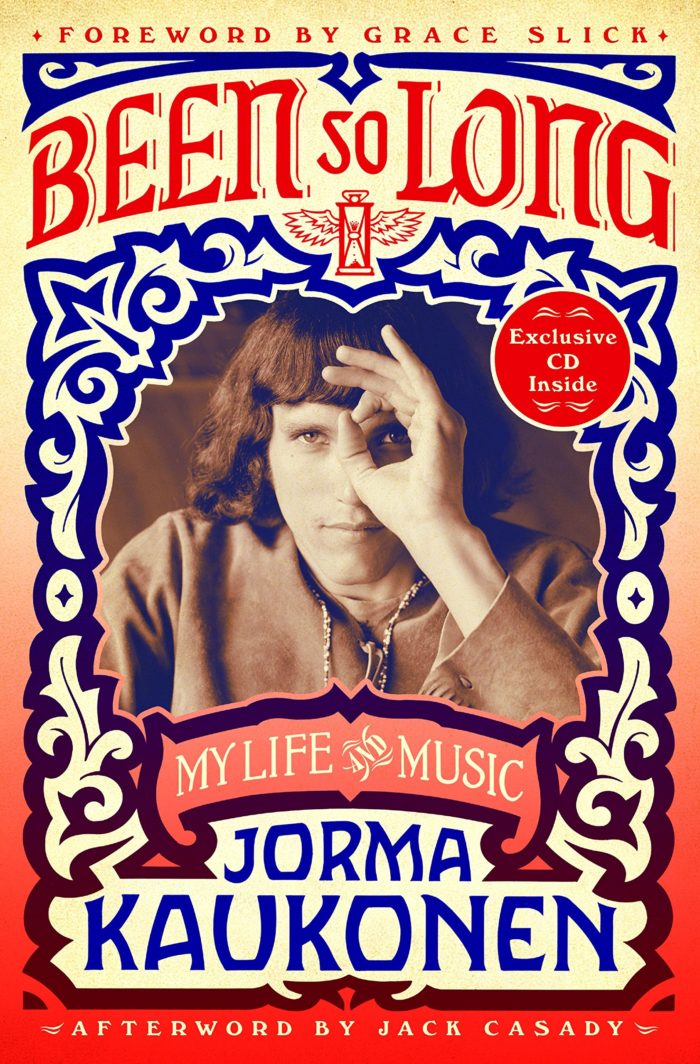

The Jefferson Airplane guitarist and Hot Tuna mainstay finally tells his story—in his own way.

Jorma Kaukonen’s new memoir, Been So Long, juxtaposes a kaleidoscopic account of the guitarist’s musical life with an introspective reflection on his geographic and spiritual sojourns. Kaukonen grew up in Washington, D.C., where he met his future lifelong musical collaborator Jack Casady, but he also crossed the globe at a young age because his father served as a State Department official.

The narrative travels to Antioch College and Santa Clara University in the late- 1950s and early-1960s and captures the intersection of the Beat era, the Civil Rights Movement and the folk revival. It then tracks Kaukonen’s stint with Jefferson Airplane (and their misguided 1989 reunion), his ongoing efforts in Hot Tuna, his collaborations with other artists (including The Band), solo records such as the Grammy-nominated Blue Country Heart and the development of his Fur Peace Ranch. It’s a fascinating work that not only looks back from the perspective of the present-day, but also incorporates contemporaneous accounts through Kaukonen’s journal entries.

As for the form and content of Been So Long, the musician explains, “While I don’t consider it diary-ing or journaling, since that stuff didn’t really exist when I was a kid, I’ve always written

my stories down. I was comfortable with that and then, in the late-‘90s, when the online world was evolving, I had a website where I would put journals up. I didn’t accept any comments, I just liked doing it because it was fun. Then, a couple years ago, my wife Vanessa said, ‘You ought to think about writing a book.’ I had never really considered that before because there’s a big difference between scribbling on a blog and actually writing a book. But, the more we got to talking about it, the more it started to make sense to me. She found a publishing company, St. Martin’s Press, that was interested in it and they let me do it the way that I did.”

In addition to a truly captivating account of your own life, many fascinating folks pass through the pages of the book, such as John Hammond, who helped you find an Antioch summer co- op job at the Rusk Institute for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in Manhattan. Did you spend much time together at Antioch?

John Hammond is one of the most interesting stories. He was a year behind me at Antioch College and came to be the John Hammond we know in about six to seven months. That’s unbelievable. We all knew, even then, he was meant to be that person. I may have known “more guitar stuff”—whatever that means—at the point of time that the two of us were hanging together, but John found his way as an artist almost immediately. Within a year, he made that first John Hammond record, then was touring as a national and, subsequently, international, artist. That’s unbelievable.

When I went to Antioch College from Washington, D.C, my extremely conservative friends who I grew up with said, “So you’re going to that pinko, free-love school in the Midwest?” And I said, “You bet.” And at that pinko, free- love school, it was pass or fail—they didn’t have grades when I was there, and they had the work-study programs, so there were all kinds of people. Many of them were activists and part of the folk scene. So there was a lot of, what we now call “Americana music” happening at Antioch College. John had tapes from his father [the longtime Columbia Records producer] of what we now know as the two Robert Johnson records that exist, but those records weren’t out yet. Reverend [Gary] Davis had already been recording since the 1920s, and there was a bunch of Reverend Davis stuff floating around, which made more sense to me. I could relate to his music more than the wild abandon that characterized Robert Johnson.

We listened to these Robert Johnson tapes and I remember thinking, “I’ll never get this.” Back in those days, if someone told you that you sounded like a black musician, it was the highest compliment. It shows progress on some level that people tend not to think like that anymore.

But John got it very quickly, he marinated himself in those recordings over the next couple of months. He went from being a student at Antioch College to all of a sudden making a record, having that record come out and getting gigs nationally. That just doesn’t happen in this business.

One of the points you make in the book is that, during that era, “authenticity lay in replication.” You write that folk musicians were expected to copy the masters. Was there a point where you feel like that changed?

I don’t think it matters as much anymore. I remember Jack [Casady], me, Jerry Garcia and Janis Joplin were just sitting around bullshitting when the Dead had a place at Olompali. And Janis and I—not to put words in her mouth because she’s not here to dispute them—were wondering, “How long will it be until we can be considered authentic?” because that was important to us. Then Jerry said, “We’re going to be archetypes,” and that sort of came to pass in a lot of ways.

Look, I never worked on a chain gang, I’ve never worked in a gold mine, and I’ve never been a brakeman on the SV Railroad. But somehow, in the playing of the songs, it’s almost as if we got to live those lives. If you hang around long enough, then you become authentic in spite of yourself.

That reminds me of another section of your book in which you’re addressing the question of whether Jefferson Airplane was a “hippie band” and you explore the demographics of your fellow musicians and that scene in general. You conclude that the answer is no, although you add, “I guess on some level we were, at least visually.”

If I think about the San Francisco scene, before the so-called psychedelic era happened, and before the term “hippie” became an everyday part of our language, people affected styles that were not the norm, keeping in mind the monochromatic styles of the ‘50s. But the artists worked really hard, and had shops and businesses—we just looked different and our art looked different.

I lived in a small college town where people thought of hippies as unwashed people who may or may not have had dreadlocks, may or may not have had jobs, and may or may not have asked for spare change. The guys in Airplane might’ve dressed funny—we wore all sorts of funny clothes and this and that—because everyone did back then, but we had a job and made money, so that didn’t really fit in with the spare change, above-the-surface demographic that many people applied to the hippie thing. And we didn’t live on a commune either! The Dead did for a while, and Janis and the guys did for a while, but Airplane never did.

Speaking of Janis, you performed with her before she became a national figure. I’ve read so many accounts of her being larger than life, even offstage. Did she seem that way to you, or more like a fellow traveler on a similar path? In reading your recollection of rehearsing together in your house while your wife Margareta typed in the background [the “Typewriter Tapes” can be heard on YouTube], it all seems very low-key.

The first time I heard her, I absolutely realized I was in the company of greatness—I’ve never heard another singer from my generation who was that good live. I’ve gotten to know Laura Joplin, Janis’ sister, over the years, and she told me that Janis was always reinventing herself. Now, the only Janis that I knew in a one-on-one way was in ‘62 through late-‘64 and ‘65, when she was still a folk-blues singer. Later, when she morphed into a rock singer, she was something else entirely. We were friends in college, but we didn’t really hang out. She didn’t have a car, so when she came down to the peninsula and needed someone to play with her, I got the call because we got along well.

Now, when PBS did that Little Girl Blue special on Janis’ life, they interviewed me for almost an hour and I’m not in that at all. And the reason I’m not is because Janis and I never did drugs together or had sex with each other. I didn’t know anything about hard drugs back then, and Janis was an esteemed colleague, for lack of a better phrase. And it was an honor and a privilege for me to get a chance to play with someone who was that good, just like it was playing with Grace [Slick].

Your mention of Grace leads me to Jack. I think many readers will be surprised to learn that when you invited him out West to become Jefferson Airplane’s bass player, you had never heard him play that instrument.

Jack is one of my oldest friends, and he’s a really interesting guy. If you were to talk to Jack today, that’s the same Jack he was back then. His vocabulary’s gotten bigger, but he hasn’t changed a bit. He was a guitar player in our band [back in D.C.] and he always spearheaded the business opportunities—he wasn’t the manager, but he made sure things happened. When we were looking for a bass player, I’d never heard him play bass, but I just knew that he was gonna be good.

Jefferson Airplane was an electric rock band, but most of your focus before you joined was on solo acoustic folk and blues. In Been So Long, you reveal that hearing George Harrison’s solo on The Beatles’ “She’s a Woman” impacted your perceptions of rock music.

In that era, I looked down at the rock- and-roll thing. However, when I first heard that solo, driving up the 101 in this ratty, old Volkswagen, I understood what was happening in that music genre. Even though I listened to a lot of rock, I’d never really figured out what was going on. As a solo, acoustic-guitar player, every song is a piece for you. But in a band, every band member has their duties, and George performed his duties well with that one solo. I heard the tone, I heard what he did. He came in, said what needed to be said, and was gone. And then they were back to the song. Just in that moment, I finally got what was going on.

Speaking of guitarists during that era, did you ever play with Duane Allman? You don’t mention that in your book, but he was close with John Hammond and, as I understand it, they recorded and performed together in non-formal settings, akin to your “Typewriter Tapes” with Janis.

I never had the honor to play with Duane. I’ve played with Dickey [Betts] and some of the guys since then, of course. I heard the Allman Brothers play at the Carousel. John had told me about Duane and had played me some tapes they did together and, of course, there’s a certain aspect to the Allman Brothers’ sound—the parallel, two-guitar harmonies and stuff—that, in a way, we take for granted because a lot of people have done it since then. But at the time, it was earth-shaking; it was unbelievable. The fluidity Duane had as a slide player, I’d never seen before.

To my mind, Papa John Creach has been somewhat lost to history. Do you think he experienced any culture shock when he performed with the Airplane or Hot Tuna?

Papa John—what an interesting guy he was. He had such a rich history. If you go onto YouTube, there’s this clip of him in a movie [Blue Gardenia] playing with Nat King Cole and an upright-bass player in a restaurant. Papa John had done everything. Joey [Covington] and Marty [Balin] met him at the Paris Club in LA. They brought him up to Winterland, asked if he could sit in and he became a de facto member of both Hot Tuna and Airplane for a number of years. He knew no boundaries as far as music was concerned. For him to play with the rock- and-roll kids seemed as natural to him as playing with a symphony orchestra in Pennsylvania years before or in a movie with Nat King Cole. I can’t speak on his behalf, but my take is there was no culture shock whatsoever. He was utterly comfortable in whatever situation he found himself.

What has teaching at Fur Peace Ranch taught you?

When you start something like the Fur Peace Ranch, you never know what form it’ll take or how it’ll touch people’s lives. There’s a certain aspect to it that sounds a little sappy when you talk about it in interviews. It has a lot to do with the personality, and the musical community of like-minded spirits.

As a teacher over the years—we’re coming up on 30 years—I can’t even begin to tell you how much I’ve learned from my students by them allowing me to teach them. It’s made me a better musician. I know what I’m doing now. I not only think about my playing, but also other people’s playing in general, in a much more satisfying, under-the-skin kind of way. Whereas before, I was good at what I did, but I couldn’t explain what I was doing to anybody. As an older player, my ability to be able to replicate things slowly and precisely—almost like a Tai chi, martial- arts exercise—makes me a better player when I’m doing my own thing.

Now, I can’t prove it, but I have no reason to disprove that there are certain places that are right for you and, as I’m sitting on my porch overlooking this little valley with a little river, for some strange reason, Southeast Ohio is just right for me. I don’t know if it’s because this is ground zero for the beginning of the French and Indian War, or that Tecumseh was from here, or all these other things. However, it’s certainly been proven to be the case. I’ve been living here almost 30 years now, and I’ve never lived anywhere that long, ever. This just seems to be a place that has been important to my development as a human being.

This article originally appears in the October/November 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.