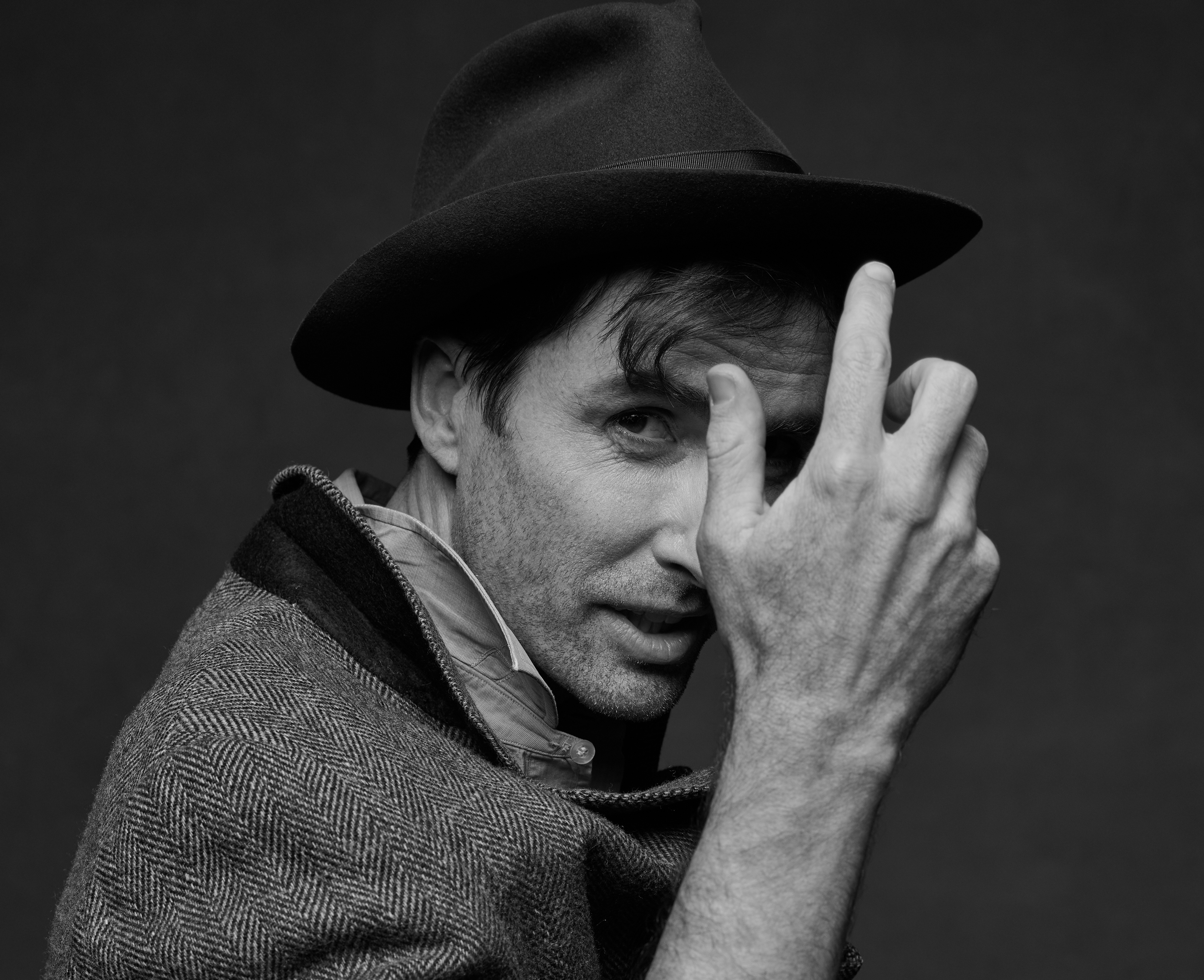

Interview: Andrew Bird

photo by Amanda Demme

After stepping away from the studio for a few years and meditating on some unique sacred spaces, the noted violinist and whistler conjures an old-school jazz spirit on his new, timeless set.

Andrew Bird has long felt tied to a different time. From his trademark blend of violin, vocals and whistling to his flair for pre-war swing and onstage gramophones, the 46-year-old, Illinois-bred indie musician has always been able to step into another era, even as he’s experimented with modern looping techniques, garnered hipster acclaim and hosted his own web series, Live From the Great Room. And, for his first proper studio project in three years, My Finest Work Yet, Bird has stepped into the past with his approach too, consciously tapping into the “jazz room sound” of esteemed engineer Rudy Van Gelder by recording live to tape with his band at Barefoot Studios in Los Angeles.

“The reward for doing it this way is that you get a real interplay between players, but it’s challenging trying to sing over the band—live, with no headphones,” Bird says of the project. “It’s not easy to do all that live, in one take, and to live with it for the rest of your life—you just have to hope you’re on that day. But it’s worth the risk because the end results don’t sound like the records that are made today.”

But while Bird managed to recall the warmth of those “scrappy, but really good records from the late-‘50s, early-‘60s,” My Finest Work Yet’s subject matter is anything but retro, diving into some of the more divisive issues of the current political era.

“One of the overarching themes is the ‘intimacy of enemies’ phenomenon—people needing to have an enemy,” he says. “What if you were to just turn your back on that person and walk away? We’re all playing our part and being manipulated by the system. That’s a pervasive theme, from ‘Bloodless’ to ‘Archipelago’ to ‘Proxy War.’”

Though My Finest Work Yet is Bird’s first traditional album since Donald Trump assumed office, the violist has remained busy, thanks to experimental projects like his field-recording series, Echolocations. He has also recently confirmed a role, designed specifically for him, as Thurman Smutne in the FX series Fargo. And, he’s always on the lookout for a unique space to add to his docket. “Part of my whole ethos is responding to the room—that extends beyond the live performance and into the recordings I’m trying to make with Echolocations,” he says. “I don’t want to force my repertoire on the room or whomever might be listening. Part of my religion is playing to my environment and creating a room that we feel good in.”

It’s been a few years since you’ve released a traditional studio record. Did you continue to write during that time?

I’m writing all the time, whether there’s a goal or not, but I don’t write anything down. I keep it all flowing in my head and then, I’ll have this very anxious sense of urgency, and that’s when I have to get these songs down. I’ll get very apprehensive about these new ideas.

About a year or so ago, I started talking to people about who I was going to make an album with. I was gonna work with Blake Mills originally, but he wasn’t going to be ready to go into the studio so I said, “I can’t wait—I just have to do it.” I met with Paul Butler, who I already admired. We spoke and, an hour or so later, I said, “Can you start on Monday?”

Your approach was partially inspired by studying Rudy Van Gelder’s techniques. What, in particular, moved you about the albums he engineered?

I’m no stranger to live-band recordings, but I wanted to take it a step further with this one. We talked about getting that bleed between the instruments and the mic just right—where most of your drums sound like they are coming from the bass or you have to be cool with how your vocals sound because, if you try to change them, then you’re gonna change the drum set, like on a jazz record. For the last 40 years, the trend has been to isolate every sound so you can control it in the mix, and that’s a very risk-averse approach to recording.

I always like to have a counterpart on a record—the last time, it was Fiona Apple and, before that, it was Tift Merritt and Nora O’Connor. I like having that different point of view or else I get turned off. So, this time, I brought in Madison Cunningham, a phenomenal singer-songwriter, and incorporated her into the band. I started working with this piano player, Tyler Chester, who nailed this really tasteful, really ‘60s, Herbie Hancock soul-jazz sound. My drummer, Ted Poor, has amazing dynamics—he can play really quietly and also groove.

I always come back to jazz music. I made my first two Bowl of Fire records in New Orleans in the late-‘90s and spent a lot of time down there—New Orleans is a heavy place for me for various reasons—and then, I did a record with Preservation Hall Jazz Band. Whether it’s obviously in my music or not, the spirit of that music always drives how I make my own music.

You’ve released two volumes of field recordings as part of your Echolocations series. How has that experimental process influenced your songwriting approach?

Being an instrumentalist—a violinist—I love having to write a melodic, concise song but, if that’s all I did, I would be mutilating a whole part of myself that loves to experiment and improvise, so I create these projects to give me that room. I just stumble onto them and I’m really driven by my curiosity. I’m a bike rider and, with the Echolocations [series],

I’ll find a space and say, “It

would be cool to play here.

I wonder what it will sound

like, and what it will tell me

about where I am? How can

I build a composition based

off that?”

When you play a theater or a club every night, you try to eliminate frequencies that are troublesome. In this case, you keep those because they’re telling you something and [influence how] you structure your composition. I’ve played these sacred spaces—churches, synagogues—and thought, “What if I take the roof off? What if the space could have an acoustic property outside?”

It is a similar idea on a human level with [my web series] Live from The Great Room. When I was promoting the last record, I didn’t like the way I was having to talk about the personal nature of the record and I tried to change the script. These complete strangers would come to my door and, within half an hour, we’re creating great music together. [Bird made his previous record in the wake of his wife’s battle with cancer and the birth of his first child.]

You’ve played a number of these sacred spaces, in different regions, around the holidays as part of your Gezelligheid series. What was the initial goal for those shows?

It had to do with getting through the winter. I did 36 long, dark winters in Chicago. That’s what the holidays are all about with the lights and everything. It was about trying to bring people together to create some warmth.

I didn’t move to New York or LA when everyone was telling me I should for my career. When I was 29, I moved out to a barn in the country, in the middle of winter, and no one understood what I was doing. They said it was career suicide and, in fact, it was. I didn’t know what I was doing myself, but I wouldn’t be making the music I make now if I hadn’t done that. But, after a while, just for a lot of personal reasons, Chicago became…it just starts to haunt you after you live there for a long time, and so I had to go somewhere else. I went to New York, got married and started a family. But I found it tough so I moved out to LA. And there’s a great scene out here; a pretty strong community right now. There are lots of musicians who are all very open to playing.

Your surroundings clearly impact your songwriting approach. Did your move to LA shape My Finest Work Yet?

Sometimes the environment is the enemy of the song I’m carrying. I have a ton of voice memos, and I get to most of my ideas when I am on an airplane so I can’t really say what this environment has to do with the music I’m making. But you certainly have to be aware here because it is such a professional town—people come here to get paid, but that doesn’t make it easy to sound professional. I’ve been around long enough to know that’s the risk, but the flip side is that the caliber of the place is amazing. I worry how it would have affected my music if I came here when I was too young.

My Finest Work Yet also digs into current events and America’s political climate much more directly than your previous releases.

I would say that 80 percent of the record is political—dealing with the world that we’re living in and my take on a lot of the things that are going on. With a lot of the songs, at first, you might think I’m talking about personal relationships when, in fact, I’m actually talking about macro-global conflicts, but I’m trying to look at what’s going on in a way that’s above the chatter. There might be a little less humor in the lyrics on this record, but I think I’ve earned the right—after doing this for a while—to have fun with the title and the cover of the album [which recreates the 1973 Jacques-Louis David painting The Death of Marat]. Those are there to play off the seriousness of the songs. If I just came up with a poetic, deep title and a poetic image, it would be laughable to me. It’s a commentary on how we are not exactly living in an age of discretion.

Do you attribute that shift in your songwriting to the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath?

It’s not always so deliberate—it’s a reaction to the world I live in. I did feel some pressure, at first, after the election. People were coming up to me and saying, “You have a voice, you gotta do something” in a panic. But you are like, “I can’t just write a protest song; it doesn’t fly.” If you really wanna go beyond “quiet,” you have to make an incredibly charming-sounding record. You have to infiltrate and get people talking about it. But just rage-and-anger music is not going to move the needle at all.

It was a balancing act—how explicit do you get about what’s going on? I established a line and moved the line as far I could go. A song like “Fallorun” is as close as I can dare to get because of the pitfalls you get pulled into, the ugliness. I want it to be fresh and untainted, as much as it can be. I did these shows at the [LA club] Largo where we talked with people like Shepard Fairey and Jenny Slate in the middle of the show. I want to bring in people with brains, like Malcolm Gladwell, to try to elevate the discourse and talk alongside the music.

This article originally appears in the September 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.