“I’ll Take My Chances on an Acid-Soaked Jimi Hendrix”: Seeing Sound with Johnny Cash and the Owsley Stanley Foundation

“When my dad was alive, I would go with him on occasion to visit the tapes,” Starfinder Stanley says of the 1,300 soundboards his father Owsley “Bear” Stanley originally recorded while working as a live soundman for the Grateful Dead, and many other artists, from the late-1960s into the early ‘80s. “They were in the vault with the Dead tapes before the vault got shipped off to Southern California when Rhino took it over. He would pull out different reels, look at the writing on the box and have all these memories specific to each show.

“He knew that there was a lot of music that potentially could be made into different albums but, at the time, the technology wasn’t mature enough to do the transfers and the internet wasn’t mature enough to be able to connect people easily. It was always a project that he anticipated doing but things hadn’t ripened yet. He was off in Australia and he didn’t quite have enough time on his odometer to get to the finish line with the reels.”

After Stanley died in 2011, the disposition of his audio archives fell to his family. Hawk Semins, who became Starfinder’s close friend after Owsley introduced the two as teenagers at the Dead’s 1990 Albany run, recalls: “We figured that, given the volume of tapes, it would take two engineers working full-time— for two years in the studio—to preserve all the tapes. Looking at their hourly rate, we calculated how much it would cost. And, of course, none of us could afford that.”

In response, they formed a 501(c)(3) nonprofit with the hope of digitizing the archives. The first infusion of funds came in July 2015 through Fare Thee Well, where the Owsley Stanley Foundation tabled as part of HeadCount’s Participation Row and later received proceeds from its charity auction. Four months later, Hot Tuna performed a benefit show for the foundation at the Great American Music Hall.

Semins explains, “It was between those two events that the preservation mission was commenced in earnest. The Doc and Merle Watson box set—seven CDs and 94 tracks—was our flagship release and we realized very early on that we didn’t need to do capital campaigns and beat the streets. If we could put out one or two every year, that would fuel the preservation effort.”

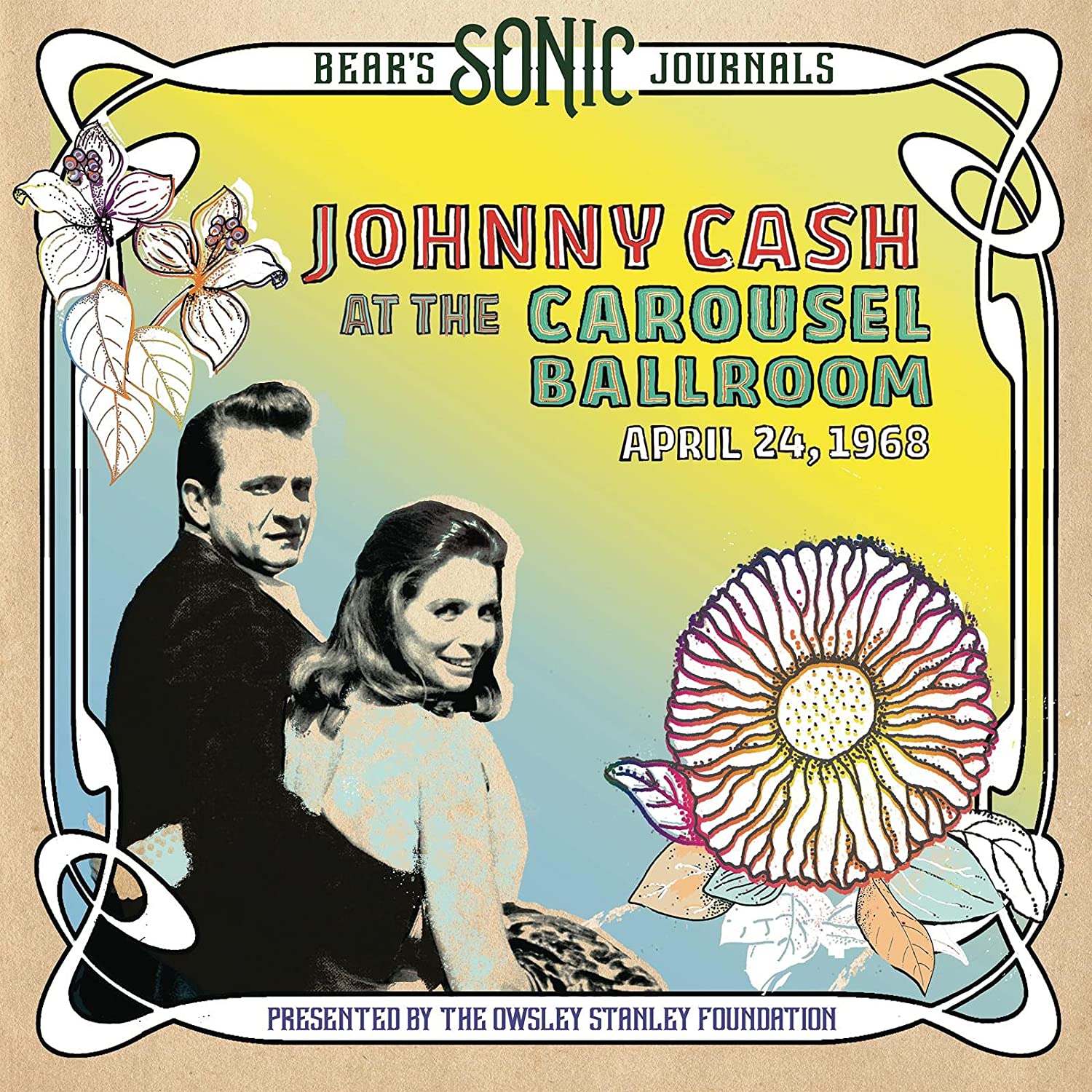

These releases, known as Bear’s Sonic Journals, have also included classic performances by Ali Akbar Khan, the Allman Brothers Band, Tim Buckley, Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen and New Riders of the Purple Sage. The latest offering presents Johnny Cash, June Carter Cash and the Tennessee Three at San Francisco’s Carousel Ballroom on April 24, 1968. Johnny Cash at the Carousel Ballroom also features extensive liner notes, including essays from Bob Weir, John Carter Cash and Dave Schools.

As for the name Bear’s Sonic Journals, his son says, “He was really adamant about what a sonic journal was. Bear called them his sonic journals because they were his tool to improve his sound systems. He was trying to capture, as precisely as he could, what the audience was experiencing at the show so that he could make the systems better.

“Also, in the early days, he would take the band back to the hotel right after shows, sit them down and make them listen. He wanted to put the band in the audience’s place: ‘This is what they got. Is it what you were trying to give them?’ I think that was crucial because it helped these bands figure out how to transmit their vision in a more pure fashion to the audience.

“He recognized that there was something about the magic of the live performance. He always said, ‘I’m not a recording engineer.’ His sonic journals captured his art, which was creating live sound for concerts.”

Bear’s Sonic Journals debuted with an ambitious box set from Doc and Merle Watson. What led you to include all four shows?

STARFINDER STANLEY: To begin with, Bear’s Sonic Journals are not focused on the Grateful Dead. Dave Lemieux and Rhino have that well in hand. We collaborate with them when they want to use Bear’s tapes but, for our Bear’s Sonic Journals series, we’re focused on the 80 other artists who are not the Grateful Dead.

So, as we were trying to figure out what to do for our first release, we heard the transfers of Doc and Merle. They were so exquisite that we knew it right away. This was eight months after Old & In the Way, which Bear recorded at the same venue [The Boarding House in San Francisco] and that album is renowned for its sonic quality and clarity. Bear really knew how to mic an acoustic band in this venue.

We started listening to it, and each reel was so good. We were going to do a single CD release but we weren’t sure which night to pick. Then, we looked at each other and we were like, “Why can’t we do them all?” A lot of times, people won’t release multiple shows because there are multiple iterations of the same song and people don’t want to pay royalties four times for four different versions of the same song. But we’re a nonprofit, this isn’t about making money. Bear’s philosophy in life was alchemy, so this is about: How do you transform the base elements into the purest gold?

We talked to T. Michael [Coleman, the bassist on these May 1974 performances]. We said, “We’re thinking about doing the whole stand of shows. How do you think people are going to respond to that?” And he was like, “Hell, we never played anything the same way once, much less twice. I reckon you’ll be fine.” We realized that was the name of the release right there: Never the Same Way Once.

You’ve issued two versions of the Allman Brothers Band shows from February 1970 at the Fillmore East—a compilation and the complete run, which includes some gaps in the music. What prompted that decision?

SS: Bear felt that his sonic journals were the closest way to experience what it was like to be at that concert. He never wanted to go back and edit in any way. If a musician ever asked, “Can we fix that in post? I was a half-step off for three bars,” then he’d say, “No, the time to fix that was in ‘68 because that’s what you played and that’s what they heard.” For Bear, the magic part of that sonic journal was the time machine, being placed in the audience at the show and hearing it as it happened from start to finish.

Sometimes he’d even miss things because it wasn’t his job to record, it was his job to mix sound. So he wouldn’t always push record right when they started the show or the tape might run out while he’d be doing something else and wouldn’t notice. His response to that was, “Yeah, well, sometimes you gotta go take a leak.” Part of going to a show is that occasionally you miss stuff. Somebody starts yelling at you or something happens but that’s the veritas of live performance; it’s warts and all, for better or worse. So we try as hard as we can to stick to Bear’s philosophies, while, at the same time, recognizing that sometimes you have to make some compromises for listenability.

When Bear recorded the Allman Brothers in February 1970, he hadn’t seen them play live before. He didn’t know that 15 minutes of tape was not enough to get all of “Mountain Jam.” So there are some heartbreaking moments in the reels, where they’re going full-bore and they run off the cliff because the tape runs out.

The Allman Brothers did a compilation back in the ‘90s, and they spliced together a number of different tracks from the different nights to make one continuous show. Bear understood why they wanted to put it out; he knew that they wanted to make the complete experience. He railed against it because he felt it was a compromise that didn’t give you the full sense of what happened but he allowed them to do it.

So we went back to them and said, “This is out of print. We really want to have this be a chapter in the Sonic Journals series.” And they said, “OK, but with the tape breaks, we can reissue the original compilation.” We said, “Well, OK, if we’re going to do that, then let’s start fresh.” So we re-transferred all the reels, then Jeffrey Norman recreated the compilation and did a whole new master.

At that point, we said, “While we’re at this, why not let us do the Sonic Journals the way Bear wanted, which is all of the shows in their entirety or as much of them as we have. We’ll give people the compilation, but we think people want to hear the rest of it.” It took some convincing, but they came around. I mean, who wouldn’t want to hear the rest of it? You have the first three live versions of “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” ever recorded. It had been written like a month earlier. Where else are you going to get that?

You started off with 1,300 tapes that needed to be preserved. What’s the state of the archives now?

HAWK SEMINS: We’re 829 reels in and we’ve got fewer than 500 to go. We don’t recreationally listen to any of it. If there’s a tape that’s unmarked and we don’t know what’s on it, we won’t listen to that tape until it’s marked for preservation. So there may be all sorts of gems that are hidden in the archives, but we’ll have no idea until we preserve them and then hear them for the first time as they are being preserved.

Can you think of something that you discovered in the first 829 that just blew you away?

HS: Oh, my God, there were so many things. I mean, just look at our Jack and Jorma release. It took two-and-a-half years to piece that together because portions of that show were on the front and back ends of the opening and closing performances from that night. There was only one tape that was labeled from those shows at Veteran’s Memorial in Santa Rosa, Calif. [on June 27 and 28, 1968].

The Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band opened the first night. Then, Jerry joined them on pedal steel for “A-11,” the tune Buck Owens popularized. He stayed on pedal steel when the Grateful Dead opened the middle set with “Ole Slew Foot” and closed with “Green, Green Grass of Home.” Then, there was “Drums” before Jorma and Jack took the stage. The next night, they flip-flopped—Jorma and Jack were in the middle and the Grateful Dead closed.

We had pieces of Jorma and Jack everywhere and only one reel that was actually labeled. I suppose we should have known to go back and look for the whole thing but it’s not that linear sometimes.

We also find guest artists that we didn’t expect on the reels all the time.

SS: There are a lot things hiding in the nooks and crannies, like the first live performance of “Teach Your Children.” They were filling time between sets and said, “We just wrote this song and haven’t played it for anybody yet, but we’ll give it a shot.” Those sorts of moments make the hair on your arms stand up.

But it can go both ways. I remember Bear pulling out a tape and looking at his notes on the back: “It says very weird. That could be good. Maybe not, though…”

There are also shows that didn’t quite make it. There’s the tale of Bear recording Jimi Hendrix tripping on acid at the Masonic Temple in San Francisco. At the peak of his trip, Jimi grabbed the reels off the machine and hurled them into the fire. When I heard this story, I was like “Noooo…” But Bear said to me: “Well, you know, sometimes it doesn’t sound better the next day, so maybe it was for the best.” I was like, “I don’t think so. I’ll take my chances on an acid-soaked Jimi Hendrix.”

HS: Sometimes the boxes are marked incorrectly, too. For instance, we’ve been working on a project with Phil Lesh where we’re looking for a certain set of tapes. I’m going to sort of sidestep this a little bit, because I don’t want to get into the details, but it’s a very interesting performance, not in the typical musical idiom that you would expect. Phil remembers hauling the equipment there with Bear to make this recording. We found four sets of tapes that seemed to match the description. One of them was a Grateful Dead tape at Winterland, which clearly had been mislabeled or Bear had taped over it.

It’s a situation where we have copies of the tape that Phil is looking for but we’re still hunting for the master. My greatest fear is that Owsley accidentally taped this Grateful Dead Winterland show over the top of the tape that Phil is looking for. But that’s an example of the kind of mayhem in the archive. At some point, the question for Phil might become, “Do you want to release a copy if we can’t find the master?” Meanwhile, the hunt goes on.

I know you don’t like to discuss specific tapes in the archives. But if you’ll indulge one question, did Owsley record Miles Davis when he opened for the Dead?

HS: Yes, he did. We’ve already started discussions on that. All the parties are aware of our interest. We want it to happen and we have a really interesting idea about how we would approach it.

When it comes to the mystery reels, do you have some kind of diary that helps serve as a guide to figure out where Owsley might have been on a given night?

HS: Typically the distinguishing landmarks are where he was in his relationship with the Grateful Dead and the law. We know that he was in prison from July ‘70, until roughly September ‘72 [on federal charges of manufacturing and possessing LSD]. We also know that he was limited to California from roughly March of ‘70 until he went to prison, so he missed a lot of amazing Grateful Dead things on the East Coast during the spring. But the whole reason we have the Ali Akbar Khan recording [from May 29, 1970 at the Family Dog in San Francisco] is because the Grateful Dead went to Europe, and he couldn’t go with them.

We all knew that the Ali Akbar Khan tape was going to be special because Bear put stars on the back of the box. Bear wasn’t effusive, so when he’d say “good” or he’d use an exclamation point or he’d put stars on a box then you knew that it was something good. The Ali Akbar Khan release was also the fastest to earn back its costs.

I think it’s important to mention that we’re all volunteers. None of us have made a penny from this and none of us intend to make a penny from it. We pay the musicians, along with the engineers, the graphic artists, that sort of thing. But no family member or board member who works on a project gets a dime. It’s all for love.

You’ve been working toward the Johnny Cash release for a while now. Was that another one of his favorites?

SS: Yes, it was one of the reels on Bear’s short list that he felt was prime picking for release. It’s funny because I remember my mom talking about the show when I was a kid.

It’s a really different way of experiencing Johnny Cash and June Carter, at a point that was so pivotal. It was the week before Folsom Prison dropped and Johnny’s career was on a downswing. He’d had a lot of trouble that year, then his divorce came through and then, a month-and-a-half before these shows, he married June, the love of his life. They came up to the Carousel Ballroom, which was this 1920s dance hall that could hold a couple of thousand people, but only 700- 750 people came out that night.

So the show feels remarkably intimate and that’s accentuated by the way that Bear was recording at the time. He had been experimenting with different ways to try to capture the sound so that the audience experienced it with as much clarity and separation as possible.

There had been a night when he was moving out of the sound booth and running around where he had an episode of synesthesia. He had taken a large amount of LSD, crossed some wires in his brain and, as far as he could tell, started interpreting the sounds coming through his ears with his visual cortex. So he was actually seeing sounds coming out of the speakers and reverberating around the room. He said it didn’t look anything like what he thought sound should look like, which blew him away. He said he was quite out of his gourd, but he sat down and told himself: “This is really important; you’ve got to hold onto this.” Not every revelation that comes to you in the throes of an acid trip stays put but, that one he really tried hard to hang onto because it informed how he mixed sound.

He always used stereo mics. When he would mic a source, he would do it with two mics. But now, instead of running the right channel into the right track and the left channel into the left track—and then having two tracks that mirrored the right and left from each of the pairs of mics— he would run a portion of the sources into one track and then the rest of the sources into the other track so that each track had completely different information on it.

The effect is of being right at the front of the stage. There’s distinct separation between the different musicians because they’re in different speakers. That really brings you back to this almost acoustic sort of experience of having Johnny on this side and the Tennessee Three on that side. And you’re right in the middle. It creates a clarity that’s hard to put your finger on.

Along with your ongoing preservation efforts, you have an adopt-a-reel program, where people can donate $400 to help preserve a specific tape. How does that work?

HS: I’ll reach out to the patron with an email that explains that we don’t share our lists but we will work with you directly to find a match. It’s as proactive as they want it to be and, typically, what we do is make suggestions.

We have four categories of tapes that we look to when making our own priorities. One of those is “interesting combinations of artists.” Another is “unusual or rare performances”—something unique has happened that we’re aware of or it’s a historically important date.

A third consideration is identifying the tapes that are the most at risk. We love it when patrons are willing to take a gamble and say, “You know what, I want to preserve what needs to be preserved first, so that it doesn’t deteriorate any further.” That’s a more interesting engagement because Jeffrey then goes and finds those distressed tapes, usually from the ‘70s at this point, and prioritizes those for preservation.

The final criterion that we’re using is lesser-known artists. There are a number of artists that, for whatever reason, time has forgotten. But we still believe that their tapes are worthy of preservation and study. We want to figure out who these people were and why Bear liked them enough to tape them and then keep the tape around. Tape is expensive and Redbird, his daughter—she’s an officer on our board—has said, “There were times when my dad would spend money on tapes instead of food. He always figured he’d have enough money later for food, but he might not have enough money for tapes.”