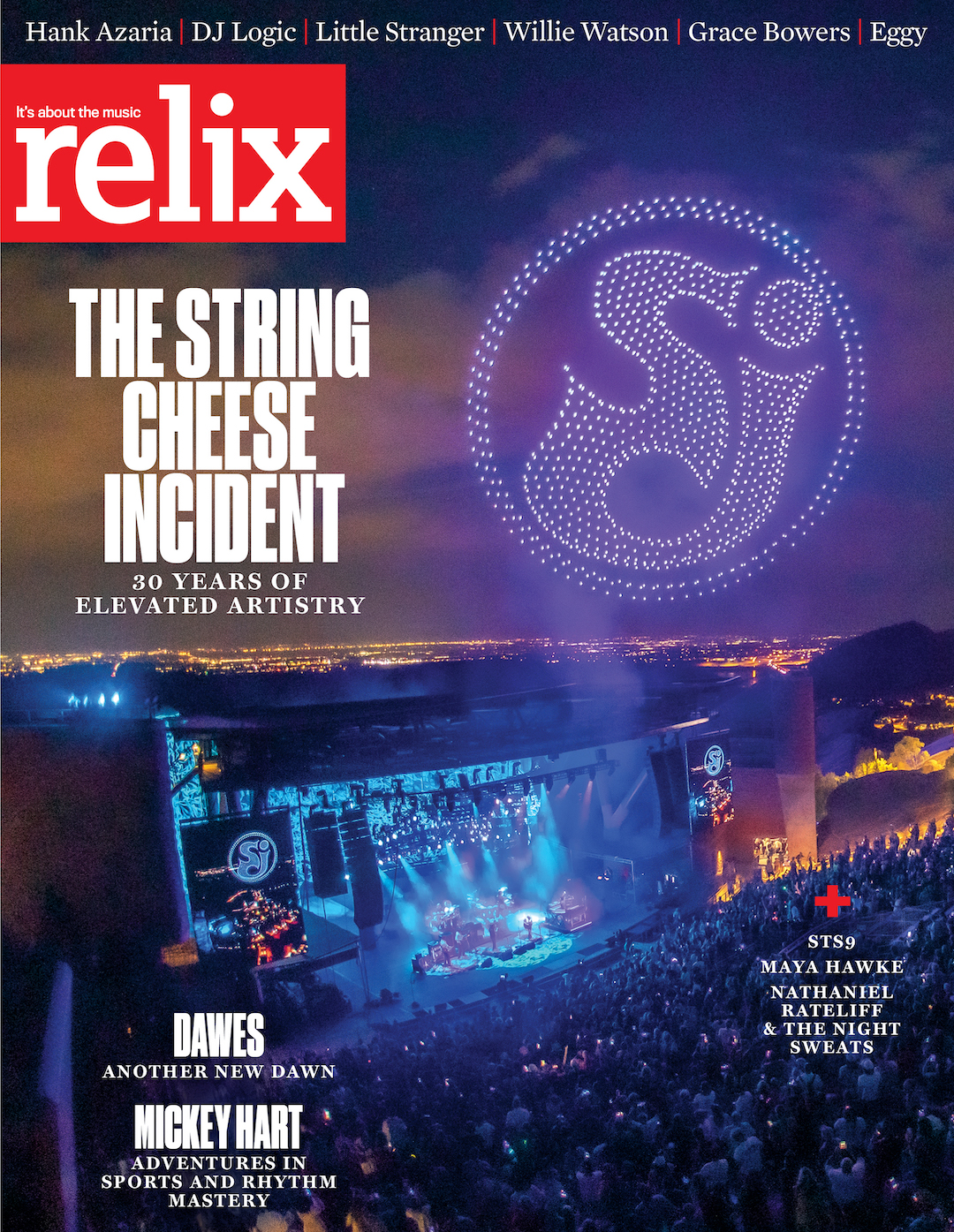

Houndmouth: This Americana Life

photos by Claire Marie Vogel

After being pegged as a harmony-laden roots-rock combo for years, Houndmouth knew they wanted to make a change on their next LP. But even the band’s most loyal fans couldn’t have predicted what came next—a cosmic journey far from their earthy Americana origins, co-piloted by Shawn Everett and Foxygen’s Jonathan Rado.

“This better be a freaking joke.”

“Good job evolving into a laptop.”

“Genuinely dejecting.”

When Indiana rock trio Houndmouth released “This Party,” the first single off their third album, Golden Age, online comments from fans showed they were, well, less than pleased. The song has all the ingredients for an indie-rock hit in 2018: It’s catchy and danceable, exploring social anxiety while twirling through fields of potent ‘80s synth-pop flowers. But to many of the band’s devoted fans, those factors were exactly the problem—they were signs that one of the most beloved Americana bands of the last decade had abandoned their roots.

Houndmouth knew “This Party” would draw a backlash. The band had been crafting clever, dusty, laidback, front-porch folk-rock since 2012, inspiring countless spot-on comparisons to The Band. And, here, they were releasing what could’ve been the B-side to MGMT’s “Electric Feel.”

There was only one thing to do: Houndmouth had to embrace the hate. They knew that somewhere underneath the anonymous cyber bashing there was still a spark of love.

“We watched these reactions to the song: Someone would heavily critique it, then the next comment would be something harsher. Then the first critic defended us to the second, like, ‘Hey, you’ve crossed a line. Take it easy, guy,’” says Houndmouth bassist Zak Appleby. “It’s like how nobody can call your best friend an asshole except you because you love them the most.”

Eleven days after “This Party” hit the internet in May, Houndmouth dropped another video—a grainy VHS clip listing the harshest comments in ‘80s retro-futuristic fonts.

“Someone wrote, ‘Ruined my morning,’” says drummer Shane Cody. “I loved that one.”

So how could Houndmouth feel so comfortable, so confident? They knew the truth: Golden Age was the most creative, artistic and relevant album they’d ever recorded, a collection of sturdy, singalong songs lit up like a Lite-Brite with odd sounds, distorted instruments and a whole slew of synthesizers. The world would just have to catch up.

Houndmouth officially formed in 2011 in New Albany, Ind., a small city of about 35,000 just across the Ohio River from Louisville, Ky. Cody, Appleby, singer/guitarist Matt Myers and keyboardist/singer Katie Toupin were newly minted adults, friends with limited recording experience but a love for rock-and-roll and each other.

A swaggering SXSW set led to a deal with Rough Trade, and Houndmouth’s 2012 four-song debut EP immediately threw the band into the burgeoning Americana scene alongside The Lumineers, Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, The Avett Brothers, The Head and the Heart and many others.

“I loved The Band,” says Myers with a frankness that suggests he knows how unspectacular that sounds. “I liked the idea of everyone singing songs in their own voices, not blending together, with all the vocal volumes equal. I liked the halftime feel, that bounce. 1970-‘74; I can’t refuse albums recorded in those years.”

In 2013, they released From the Hills Below the City, cementing Houndmouth’s well-worn but utterly infectious style: meandering folk-blues, boozy harmonies and swaying percussion under lyrics about penitentiaries, trains, postcards, coal-mining towns and being broke. The quartet wasn’t hopping train cars, but the aesthetic stuck its landing. With the release of 2015’s Little Neon Limelight, Houndmouth had a bona-fide hit: the gorgeously slow-burning “Sedona,” a song so married to the band’s yesteryear, vagabond conceit that the sound of howling wind can be heard in its intro.

But in 2016, Houndmouth faced a dual reckoning. First, Toupin decided to split. Her country-lilting voice had arguably been the band’s most recognizable ingredient, but it was time for her to create something on her own. Second, a creeping feeling finally surfaced for Myers: He’d both grown tired of his group’s sound and was becoming increasingly bored with the scene he’d unwittingly been born into.

“Every show we went to, bands were covering The Band. And I thought, ‘Shit, are we part of the problem?’ The Band invented the genre, and that time is done,” he says. “How are we going to have a genre of people replicating what happened 40 years ago? It stopped feeling like an artistic outlet, and more like bands were just banking on a sound called Americana.”

Myers knew he needed to make a change. He just didn’t know what it would look like. The ensemble—now a trio—took time off the road to relax and regroup following Toupin’s departure. That fall, they decamped to rural Gatlinburg, Tenn., to hash out some new material. They recorded a handful of demos “in our Houndmouth kind of way,” says Cody.

“We settled on just two of the 12 songs we demoed. That’s when we knew we were in it for the long haul,” Myers adds.

But those two songs, “Golden Age” and “Strange Love,” revealed a lyrical left turn for the band. The future album-title track dealt with the identities we create for ourselves online: “I’m living in a mansion on the Internet, ‘cause it helps me forge/ It’s a golden age, and you’re a satellite.”

“In our first two records, we put images in people’s heads: planes, trains and automobiles,” says Appleby. “But we wanted to present questions this time—here’s what’s happening. How do you feel about it? Are you lost in the internet? Should you take a step back, or dive in even more?”

With the new outlook in mind, the band continued working, and Myers flew to El Paso, Texas, to write more songs. There, he sequestered himself at Sonic Ranch—a residential recording studio on the Mexican border, nestled among over 2,000 acres of pecan orchards. The theme of technology—and the isolation and opportunity it presents—kept popping up. Then a conversation at the Ranch changed the course of Houndmouth forever.

“I asked a buddy: ‘If you could have anyone produce an album, who would it be?’” remembers Myers. “He told me that Shawn Everett is the future of recording. I knew we had to get in touch with him.”

Golden Age: , Matt Myers, Zak Appleby, Shane Cody

Golden Age: , Matt Myers, Zak Appleby, Shane Cody

Los Angeles producer, mixer and engineer Shawn Everett has slowly become one of rock music’s most in-demand minds, helming records by modern tastemakers like Local Natives, Grizzly Bear, The War on Drugs, Okkervil River and Mike Gordon, for largely one reason: He doesn’t care where a band comes from, only where they’re going.

“I like to know the general premise of a band, sure, but I never get too deep into their past records,” Everett says now. “I like to make a record free of that baggage. Then, when I’m nearing the end of our project, I may listen to what they’ve done in the past. And that’s when I’ll usually panic.”

When label reps approached Everett about Houndmouth, he’d never heard them before—he figured they were a heavy-metal band. But before long, all three Houndmouth members, Everett and Foxygen multi-instrumentalist/producer Jonathan Rado were all sitting in a room.

“They wanted to make a more colorful, energetic, more adventurous album—less reliant on the classic ‘band in a room sound,’” says Everett. “Whatever adventure we were gonna go on, I was ready. The real world can put fear in people. They get worried about the commerciality of their music. But in the room with me, they see I don’t care about that. Anything weird and crazy—that’s what I want to be doing. I’ve never really had a problem stoking that fire in bands.”

On their first day together, Myers brought up “Never Forget,” which, he says, “wasn’t really a song yet, just a dynamic mantra.”

“Shawn said he’d always wanted to score a movie, so we decided to make ‘Never Forget’ score a famous scene. We watched the first scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey, and that was our cue,” he says. “That was all on our first day. We knew we were on to something. We couldn’t see what, but we all wanted to move forward.”

Both Rado and Everett introduced a sense of possibility to Houndmouth: The journey was the goal, and nothing was set in stone. Along the way, they got help from an icon of openness—Brian Eno. In 1975, Eno co-created his Oblique Strategies cards, a deck of cards with one statement each to inspire creativity, like “What would your closest friend do?” and “Work at a different speed.” “The cards are like a board game for creativity,” says Everett. “I’ve been in rooms where bands take them literally and say the card doesn’t apply to them. But when [Houndmouth] pulled a card, we really dreamed up what it meant. It was my

first project where we truly obeyed the cards.” Houndmouth had entered the studio with 12 demos, and began experimenting with each one in studios across the country.

For “Black Jaguar,” says Myers, “We did it six different times, six different ways. On one, we could only use samples of Jaguar cars. On another, we only used samples of jaguars—the animals. We did a Disney orchestral version—Rado spent 20 hours in the studio with tympani and xylophones. And we played all the versions at the same time, and began muting certain parts. That’s how the song was born.”

Throughout the process, Everett and Rado brought tons of studio wizardry to the table, including the Neumann KU100 Binaural Dummy Head, an $8,000 microphone shaped like a human head.

“[Everett] told me to sing a falsetto harmony as softly and sweetly as I could, to sing in the right ear,” says Cody. “Then go to the left ear and try it again. This thing is from a horror movie—a faceless, gray head, and he was there with us all the time.”

They returned to Sonic Ranch, where so much of Myers’ songwriting had taken shape months before—“the perfect place to get weird and experiment,” says Cody.

They took a tape loop of drum sounds, attached it to the back of a pickup truck and drove it through the desert.

“We put it back on the tape machine and it sounded dirty, dusty, grimy and great,” says Cody.

They recorded bass parts by stretching a rubber band over a bucket, then manipulating the pitches that came out. They recorded harmonies by standing above a tape deck in the middle of pecan orchards, “under the stars of the darkest night I’d ever seen,” Cody recalls.

“We weren’t keeping each other in check at all,” he continues. “From day one, Shawn and Rado said whatever sound we could think of, we could create. It was so freeing. As a writer, you have the method you really enjoy—a laptop, maybe a pen and a pad—just like we had our method of drums, bass, keyboard and guitar. But then imagine someone introduces a new pen to you. You think, ‘Holy shit, this pen is incredible. I’m still writing the same words, but this pen makes me feel fucking insane. Is this a Montblanc?’”

After eight months in a half-dozen studios, Golden Age was finished—namely because they’d run out of time.

“I’ve worked on very few records where I think it’s truly done. Songs are like making clay sculptures. You don’t throw any away, you just keep crafting and molding,” says Everett. “I know a record is done when the label takes it away from me.”

To fans and first time listeners, Golden Age is wholly new and strangely familiar. The harmonies and stomping choruses are still there. The melodies still ring long after the songs are over. But these songs sound nostalgic and futuristic at once—aural fireworks perfect for pro-grade headphones or house-party speakers alike. It’s a crackling pop record made from folk songs.

And while some fans may grip tight to their traditionalist bashing, most are coming around to the idea that the members of Houndmouth have evolved—and they’ll do it again.

“I know we totally changed our sound on this album,” says Myers, “But here’s the bigger picture: If we want to make music for the rest of our lives, this is nothing.”

This article originally appears in the January/February 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.