Global Beat: Yonatan Gat

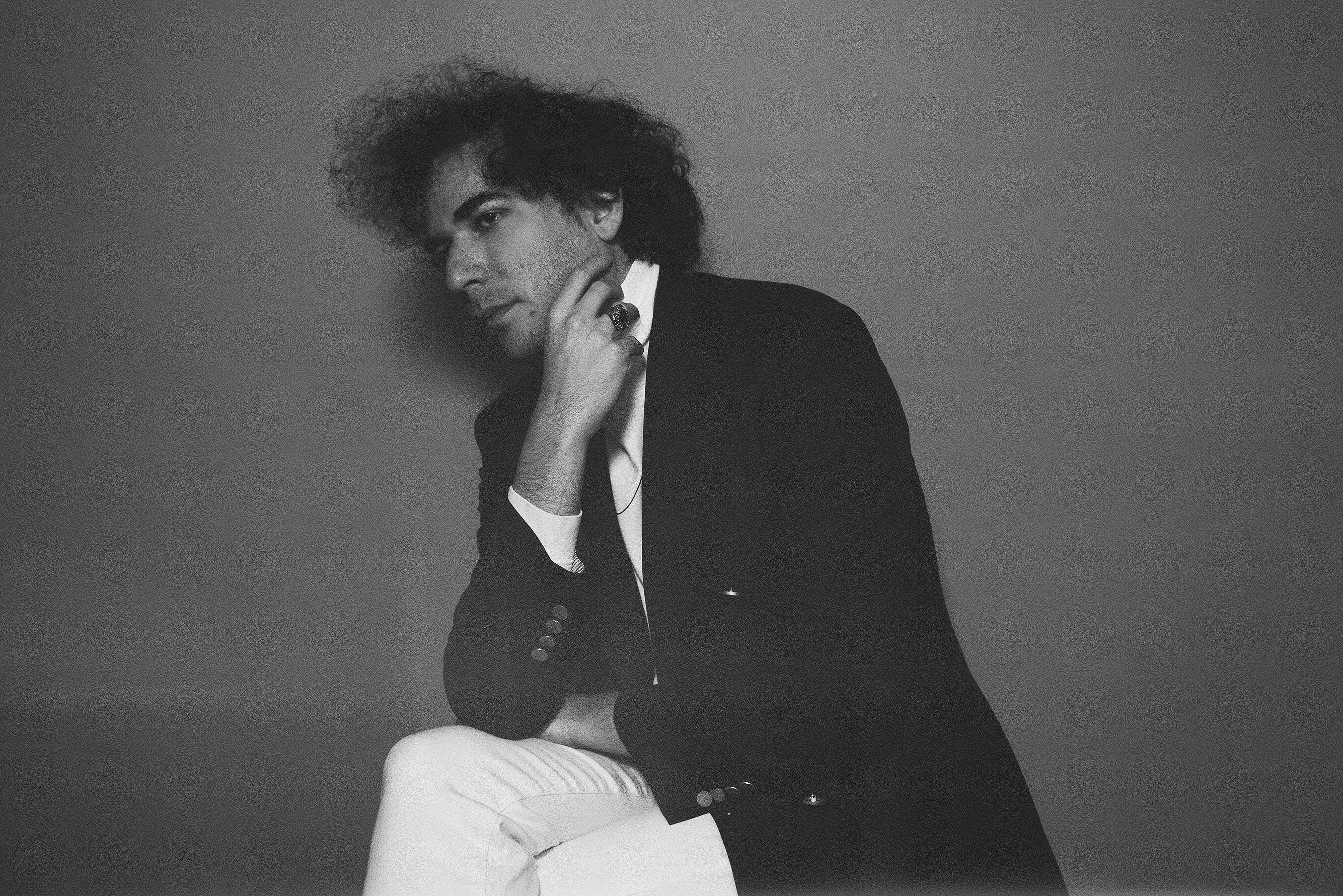

Shervin Lainez

For Israeli guitarist Yonatan Gat, music is all about connection—and not just with whoever is in the room. The man strives to reach through time and space, and his latest album, the sprawling, psych-jazz burst Universalists, is the closest he’s come to making contact.

Gat was born outside of Tel Aviv, Israel, and by the time he turned 18, he was exploring the depths of the city’s music scene and coming up empty for inspiration. He set up shop with similarly disenchanted friends at a dive bar called Patiphone that shared its entrance with a brothel; by 2005, Monotonix was born. The band’s jarring punk sound sent shockwaves through the Israeli rock scene—their shows were chaotic, explosive and unrelenting, and tapped into a truth of Israeli frustration that, Gat says, most people weren’t ready for.

“Because of Israel’s political climate, people are more prone to musical escapism than a journey that will yield the truth. There is a blockage. One promoter even threw a glass bottle at me. Our music evoked an emotion,” says Gat, noting one upside: “Because our club shared an entrance with a bordello, a lot of people had orgasms while listening to Monotonix.”

Monotonix reached a stalemate in Israel. “Exiled to move [to New York],” he says, “it was definitely not a choice. I couldn’t make music in my home country. Good music asks the hardest questions, and people don’t want to ask those questions in Tel Aviv. Tel Aviv has good food, and partying. As a musician, I need more than that.”

In New York City, he found the openness he’d sought—America, it seemed, was far more prepared to release tension and tap into mayhem. By 2011, though, the band had dissolved after tearing up tours all over the States, and Gat was on his own. He started gigging everywhere, with anyone, exploring his own gritty, improvisational style. In 2013, The Village Voice called him “the best guitarist in New York.” The mesmerizing, experimental-rock album Director arrived in 2015 and sent him tunneling into himself and toward Universalists.

Universalists album cover

Universalists album cover

Over the course of three years, Gat and his touring band recorded over 100 hours of improvisation, “some of which I’ve probably never even heard,” he says. “The record is an organism. There was never a moment when I decided it was done.” (Yeah Yeah Yeahs drummer Brian Chase, who has explored alternative Jewish music with The Sway Machinery, also signed on to play with him for a spell.)

Gat’s guiding force was the relationships he developed with music from all over the world, and the musicians who made it. While field recordings—mostly the innocuous sounds of places— added texture to Director’s songs, Gat built new music with found sounds that spoke to something inside him. “It’s so easy to find what’s different in music. But I asked myself: What is similar here?”

He heard himself, for example, in a forgotten recording of a 1950s Spanish- Italian choir from Alan Lomax’s archives. “Maybe an ethnomusicologist could explain why the music of an Israeli in New York in 2018 connects so strongly to music from Spain in the ‘50s,” he says. “But I felt it.”

The resulting composition is head-spinning: “Cue the Machines” builds the choir’s rolled R’s into a stuttering beat that jerks forward over spindly guitars and thunderous percussion. It’s musical whiplash, as thrilling as a wooden rollercoaster.

“Nothing I did wasn’t somewhere in the recordings already. I was trying to listen to the ideas in this music and understand what these musicians, sometimes from decades ago, would want from me to make it a true collaboration,” says Gat.

He felt a vivid tie to traditional Balinese gamelan music, the nonlinear melodies of which can often sound abrasive to Western listeners. “It can totally fuck you up—everything is elastic,” says Gat. “In gamelan, I heard punk-rock.”

After burying himself in Balinese recordings, the white-knuckled “Cockfight” emerged. “This riff surfaced on my electric guitar [with] the same life-affirming energy. The gamelan recording in the end came afterward—I wanted to reveal my source.”

His collaborations weren’t just with esoteric recordings. Gat invited Eastern Medicine Singers—a Native American combo—to add their vocals live in the studio. Universalists’ “Medicine” sprays jagged guitars across an open field of tribal chanting and hard-beating drums.

“When I could actually ask the musicians what they felt,” he says, “that was much easier.”

David Berman of the Silver Jews served as Universalists’ producer, assisting mainly in the ambitious editing process. “I initially felt like I was working on four records at one time,” says Gat. “[Berman] helped me realize that if I push through for years and let it rule my life, I can find the connections to make it one cohesive record.”

Universalists’ 10 songs are maybe most bound by their unpredictability, the sheer excitement they evoke while tumbling through a musical universe in which Gat is the sun.

“The album is about asking yourself, constantly: ‘Who am I right now?’ And it’s not like you find out once and run with it for 60 years until you die,” laughs Gat. “When the next record comes, I’ll be totally different. The process continues—always.”

This article originally appears in the July/August 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.