Fairport Convention: Who Knows Where the Time Goes?

Chris Leslie is perusing the bookcases in his Banbury, England home, trying to find a volume that tells the story of an 11-year-old orphan.

A discussion of the songs that he has contributed to Fairport Convention’s storied catalog since joining the band 14 years ago has prompted him to hunt down a book detailing the life of a young girl who lived in the coastal area of Lyme Regis in Dorset during the early part of the 19th century. Leslie was so taken by her story that he wrote the song “Fossil Hunter” in tribute.

While searching, he can’t help but talk about Fairport’s past songwriters – among them guitarist Richard Thompson, vocalist Sandy Denny and fiddle player Dave Swarbrick. He says that they are true songwriters but that he is only a player that writes songs.

“My view is that because I have grown up with the band, I am totally aware of all of the great songs that have come from those that have been in Fairport,” says Leslie. “I suppose a little bit of the ways [that they] wrote story songs kind of rubbed off [on me]. Songwriting is a 24-hour a day job and even when songwriters sleep they are mulling things over [and carrying] notebooks in their heads. They are big observers of life.”

Leslie’s recall of the girl’s life is so clear that, when coupled with his personal observations, one can’t help but notice that he is the embodiment of his own definition of a songwriter. After a brief pause, he politely demurs, turning the conversation back to past members of Fairport.

It’s easy for those who know Fairport’s history to understand Leslie’s reticence to accept the well-deserved praise. If you’re unfamiliar with the ever-bifurcating lineup of England’s most heralded electric folk rock group, then you’re forgiven. Not many are.

But as the group celebrates its 45th anniversary culminating with their annual festival in Oxfordshire, England this August, plenty of fans are celebrating their history – and future. More than 20,000 fans from around the world are expected to converge for the three-day event in the rural village of Cropredy on and around at a 17th century country inn called The Brasnose Arms.

It’s interesting when one considers the festival began in 1979 as a farewell concert when the band members – exhausted by a host of management missteps – decided to go their separate ways. The fan reaction was so strong, though, the band played annual “reunion” concerts from 1980 to 1985 when the group was dormant.

When Fairport reformed in 1985, they continued the festival, which has grown into one of the largest of its kind in Britain. Fans and friends of the band, including Robert Plant, Cat Stevens, Little Feat, UB40, Rick Wakeman and Steve Winwood are among those that have recently played at Cropredy. Richard Thompson, Ashley Hutchings and other Fairport alums are regular guests.

Despite the star power on the bill, a good number of lesser known bands are also routinely invited to play. The only requirement to obtain a coveted performance slot, says bassist Dave Pegg who is the driving force behind the festival and also the band’s independent record label, is that Fairport members have to be fans of your music.

“It’s really a staging area for [veteran] musicians and new groups and Fairport Convention is what brings it all together,” says TJ McGrath, who founded the fanzine Fairport Fanatics, which later morphed into the roots music magazine Dirty Linen. “[Fairport Convention] are such legends, this festival is a great way to celebrate that. It also renews the band’s spirits each year. Here is a band that might lose a member here or there but will really go on forever.”

No one thought Fairport would last a few months when it formed.

That’s understandable when you consider that the band’s founder, Ashley Hutchings, was only a teenager in the mid-1960s when he and guitarist Simon Nicol started an acoustic jug band – The Ethnic Shuffle Orchestra – in suburban London. The lineup included a kazoo player and occasional guests including Thompson.

Popular culture typically recalls the Orchestra’s repertoire as eccentric, which seems fitting considering that Hutchings’ varied musical interests and desires. He never sought to “follow trends” but rather “start them,” as he says.

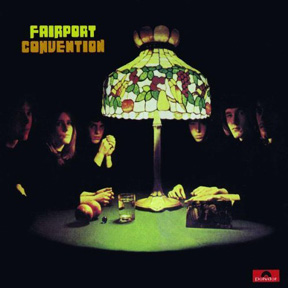

By 1967, Hutchings and Nicol disbanded the Ethnic Shuffle Orchestra and began a new collaboration that ultimately led to Fairport Convention. Little did they know that they’d become icons of a scene and sound.

“The biggest misconception about Fairport is that we knew exactly what we were doing,” says Hutchings of the band that chose its name from the Nicol family home where the group practiced. "We were all very young and grabbing [ahold] of anything we liked, very often literate songs, from Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan – just grabbing those and doing them our own way. We were almost the only group to do that.

“People were playing freaky music with light shows and extended solos, whereas we stood out because we did songs – literate, wonderful songs,” continues Hutchings. “We fell in love with traditional music and [recorded] Liege & Lief. These weren’t career moves. We were just doing what came naturally and it was all coming out in [what developed into] a Fairport kind of style.”

That style was a mix of classic and traditional folk songs, many including multi-part harmonies set to electric rock arrangements.

If the story of Fairport was a novel, then some might think that the author had used too heavy a hand to foreshadow certain events.

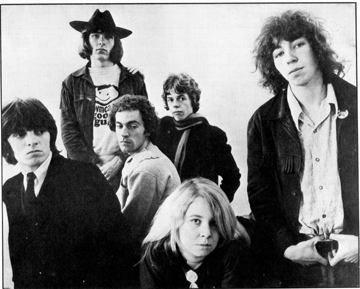

The newly minted folk-rock group that originally adopted a California rock sound many liken to that of The Byrds, was only one gig in when Martin Lamble replaced Shaun Frater on drums by. Soon, vocalist Judy Dyble though lauded for her distinctive sound, was also unceremoniously “dumped.” Her replacement was Strawbs’ singer Sandy Denny, continually hailed as England’s preeminent female vocalist. (Seriously – this isn’t hyperbole – ask any Brit.)

“I tell everyone I just wish there had been one really terrible singer between me and Sandy,” Dyble laughs before talking about accepting guest artist slots with the band at their annual Cropredy Festival.

“Years go by and it’s nice to be asked to do things,” she says with a smile. “We were all only about 18 years old [then]. How far ahead do you really think when you’re that age?”

As is the case with many young bands, poverty, immaturity and creative differences kept Fairport’s lineup in constant flux. What arguably set the group apart was its members’ musical passions.

“When I was in the band, I don’t think we had a stable lineup for a year,” says Thompson. “Things would change every six to nine months. Everything was crammed into short spaces of time. In 1969, what we used to do after a gig somewhere north of England was drive back to London and go back to the studio and go in and do a bit more. We were always recording – it was an endless process – but somehow we managed. We were all very young.”

The combined talents of Fairport Convention’s members began to pay off with more gigs, a growing fan base and a recording contract with Island Records. Although the band was not financially successful, its fortunes were certainly on the rise.

One night in may of 1969, everything changed.

On a drive home after a gig in Birmingham, the band’s van crashed. Most of the passengers were injured and 19-year-old Lamble and Thompson’s girlfriend, Jeannie Franklyn, were killed. Understandably shaken, the band was unsure if Fairport Convention could – or should – continue.

It wasn’t long after that Dave Mattacks, then a drummer in an English dance band, heard that the group was looking for a replacement for Lamble.

“All I knew was that they had a good reputation as musicians,” says Mattacks, who is hailed by many as England’s foremost folk drummer today. “I didn’t want to be in a dance band all of my life. I wanted to move into contemporary music but I was incredibly ignorant about that kind of music. I knew about Peter, Paul & Mary but I had no perception of what Fairport was doing.”

Prior to his audition – the only one he’s ever had – Mattacks bought the group’s album Unhalfbricking, released just two months after the fatal crash, and learned a few tunes. (In 2004, Q magazine placed the album at number 41 in its list of the “50 Greatest British Albums Ever.” ) Although he remembers little of the tryout, it began a stint that saw him working on and off with the band for the next three decades. At about the same time, Dave Swarbrick, who was a guest fiddler on Unhalfbricking, also joined.

Combined with Hutchings, Denny, Thompson, vocalist and guitarist Iain Matthews and Nicol, the group created what many regard as the most influential folk rock album of all time – Liege & Lief – released in 1969.

“I was in the band for about 18 months, playing the music to the best of my ability, before I really understood – from an aesthetic viewpoint – what they were trying to do,” says Mattacks. “Before that, technique was the be all and end all. I was super conscious of song form and lyric form…Then I stopped being so concerned with what I was doing and started to become much more aware of what was around me, what the verse was doing, what the lyrics were saying. It had a profound effect on how I played.”

When you think of Fairport Convention’s success with Liege & Lief and Unhalfbricking, it’s tempting to compare the group to Buffalo Springfield and The Byrds and not just based on sound. All three bands were filled with brilliant, incandescent players. All three found success at about the same time – Buffalo Springfield in 1967 with the single “For What It’s Worth” and The Byrd’s in 1965 with the single “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Most notably, all three bands began to implode almost as soon as popular success arrived.

Like their American folk-rock counterparts, Fairport Convention became rife with tension as disagreements about musical direction deepened. Hutchings left to form the band Steeleye Span, which began as a traditional folk band and moved into rock arrangements and is often cited as the second most influential British folk rock band, after Fairport. Denny left to form the short-lived traditional folk group Fotheringay. The rest of the band was in flux.

“I remember Simon and Richard meeting me at the airport [when I returned from a vacation] and telling me ‘We have some bad news – Sandy and Ashley have left,’” recalls Mattocks. “It was right after [we recorded] Liege & Lief. I remember them saying, ‘We think Sandy is irreplaceable, but we’ve got this great bass player – Dave Pegg.’”

Pegg was only 21 when Swarbrick recruited him to join Fairport Convention. Although Pegg had only seen the band play a week before they extended the invitation, he joined, becoming the only member that has never left the band. His energetic, innovative playing – often cited as inspirational by folk and punk bassists – added another element to the band’s already powerful sound.

Soon after Pegg joined, Thompson left, leaving the remaining members badly dispirited. That was especially true of Nicol, who former bandmates said was hesitant to try to fill the musical void left by a musical genius.

Although Nicol left the band a year later – which he jokingly refers to as his “years off for good behavior” – the addition of Pegg to the band set the stage for the future of Fairport that has musically morphed depending on the musical inclinations of the current line up.

“We do hear that Fairport Convention has lost its balls,” says Pegg, the longest continual serving member of the band. “There are no big keyboards, no big guitar things. To some extent that is very true; we have kind of mellowed out a bit. It’s not like a middle of the road thing but we have a much gentler sound. Simon doesn’t play much electric guitar now. [Our last studio album of original music] Festival Bell is a happy mixture of what we do.”

The band members are arguably a bit mellower, too, leaving some of their harder partying days behind. Some classic stories of the band recount how the group would drink so much during their own concerts that the tab was more than their performance payment.

Chris Leslie was only 14 years old and years away from writing “Fossil Hunter” or any other Fairport songs when his older brother John met Pegg in 1970. While chatting, Pegg invited him to bring his younger brother to his home for a visit.

Although Chris Leslie was young, he was already well-versed in all things Fairport.

“Most of my friends were carrying around Pink Floyd albums and Led Zeppelin albums – I was carrying around Fairport albums,” says Leslie. “I liked Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin, too, but I thought Fairport was so cool.”

Although Fairport were a support act for Pink Floyd, it was Fairport’s merging of styles – not Floyd’s psychedelic explorations – that caught Leslie’s ear.

“I loved it,” says Leslie recalling his earliest memories of Fairport. “I heard all the different influences in the music and they just really intrigued me. I didn’t know what they were, but I knew it was a band with character – which was what I loved.”

So loved, in fact, that when his older brother John learned to play guitar, Leslie did, too. But it was the fiddle music including that played by Swarbrick – who later became his mentor – that won Leslie’s heart. It seemed only natural that when John Leslie bought a fiddle and began to take lessons, Chris could hardly contain himself.

“When I was 13, he was 18,” Leslie says of their age split. “He’d be around town and I was still at home. I used to sneak in his room and open the fiddle case and get it out and have a go at it. It’s a funny thing because I took to it quite easily in a very rudimentary way. I probably made a terrible sound, but the concept seemed quite normal to me.”

Playing fiddle music became something of an obsession for Leslie.

“It was ever so new at the time,” he says today. “I had no background in folk music. The music might have come from Mars as far as I was concerned. Now, I realize I was always very linked to [folk music] being a European. The music’s been around this area for a long time but at that particular moment, I didn’t know that. I was just moved by it. It made my heart beat faster. I used to take [my fiddle] everywhere. Every free moment I had, I just played.”

About 40 miles from the Leslies’ Banbury home, another young Fairport fan was so intrigued by the band’s music that he, too, taught himself to play fiddle. Like Leslie, Ric Sanders’ prodigious talents led him to delve deeper into music, forming fledgling bands and playing area clubs.

“I got into all that sort of jazzy rock end of progressive rock,” says Sanders. “I’m not a singer, I’m just an instrumentalist – but I always loved folk.”

Sanders decided to write Hutchings a letter expressing his admiration for the Albion Band, another electric folk band, which Hutchings formed in 1971. The Albion Band, ranked just after Faiport and Steeleye in British Folk Rock importance, has just reformed with Hutchings’ son, Blair Dunlop, taking the lead.

“Ric wrote to me in the ‘70s,” remembers Hutchings. “That’s very unusual for musicians to do, but Ric wrote a letter to me saying if you’ve ever got a spot in the Albion Band, I’d love to join you. There was an opening [later on] and he did join and then graduated from the Albion Band into Fairport. And he’s still there playing with them.”

That, says Sanders, was a day that he never thought would arrive.

“It was a delightful shock when I got a call from Fairport,” says Sanders who Pegg also recruited. “When I went along to rehearse with the guys, I already knew all the instrumentals because I had learned them for fun.”

Sanders dismisses press reports that he was disconcerted when Leslie – who had been a member of Swarbrick’s post-Fairport band Whippersnapper – filled the slot that opened when multi-instrumentalist Maartin Allcock left in 1996.

“I was thrilled,” he affirms. “It was the happiest day of my life. Every time we got together, we talked about doing an album together.”

Calling Leslie the only true multi-instrumentalist in the band, Sanders says that his fiddle counterpart applies the same passion that he used to teach himself fiddle to almost everything else that he has an interest in.

“I have never known anyone to embrace everything with such energy and skill as he does,” says Sanders reiterating other band members’ remarks about Leslie discovering an instrument – from banjo to mandolin to Native American flutes to bouzouki – and almost immediately teaching himself to play. “That’s just what he does.”

Indeed, Leslie’s musical prowess is well respected throughout the music community. Martin Barre, best known as the lead guitarist for Jethro Tull, talked about sharing a recording session with Leslie.

“I took two or three takes to get a good one and he would come in and play once and that was it,” Barre says. “It was perfect and absolutely effortless.” He pauses when told that Leslie doesn’t consider himself a songwriter or a virtuoso player: “He is. He is a monster talent.”

Simon Nicol is spending a day at home catching up on administrative tasks for Fairport Convention shortly before they embark on their 2012 Winter Tour.

The conversation turns to fans’ devotions to various iterations of the band and their mournful fan board posts about various players’ departures.

“One of the [positives] of losing somebody is that it’s a bit of fresh air for everybody,” he suggests. “My biggest fear about the band in the last 25 years is that we would become our own tribute act. If it’s possible, I want to open up new markets – focus on new albums.”

As the band celebrates their 45th anniversary, though, they are presenting two albums of past materials. One is a live version of the 1971 album Babbacombe Lee, and the other, By Popular Request, is filled with 13 fan-chosen songs from the band’s catalog.

“It’s important that people know that although we’re a band that formed in the 1960s, we don’t live in the ‘60s,” says current Fairport drummer Gerry Conway, whose career includes playing with Cat Stevens, Thompson and Paul McCartney.

He points to Leslie’s songwriting and playing as an integral part of the band’s continued musical advancement, noting that Leslie adds banjo to fan favorite “Matty Groves” on By Popular Request.

“Currently, we have two albums from the past [that we just re-released] but that’s not the way the band operates, generally,” says Conway. “Although we try to compass [past songs] that are the basis for the group’s founding, we are a forward-going band.”

Back at Leslie’s home, his voice registers a bit of melancholy when he talks about attending the Newark School of Violin Making where he intended to spend his life making and repairing violins. He was so insistent on that path that he initially declined an invitation by Swarbrick, to join Whippersnapper.

“I still have my workshop,” Leslie says, adding that it provides something of a sanctuary for him after months of touring. “When I’m on the road, it’s very sociable. We play and come off and talk some more [to fans] so it’s very nice to have almost the complete opposite when I come home and concentrate on the bits of wood. I love getting into the workshop and working on instruments – just me and the radio.”

Although Leslie continually talks about how lucky he feels to have joined Fairport, it seems clear that Fairport could have returned to what one critic noted was a status of a “living museum piece” if Leslie hadn’t joined the band.

“It’s my belief that for Fairport to endure they must always consider bringing in younger members in order for [the music] to have a freshness,” says Hutchings. “Maybe it is no coincidence that Chris’ input is mammoth. His songwriting is so important, to setting the band apart and it seems to fit the band just perfectly. That is their way forward.”