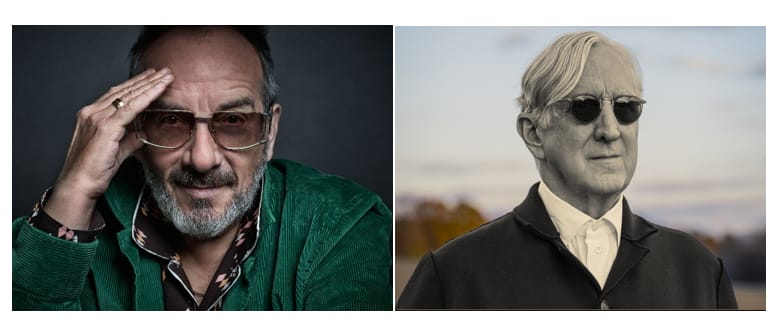

Elvis Costello and T Bone Burnett: Americana Without Tears

During a series of shows that extended from 1984 into 1985, Elvis Costello performed as a solo artist, with T Bone Burnett serving as his opener. A friendship flourished, along with a musical kinship that manifested a new collective identity as the Coward Brothers. In the summer of ‘85, the Cowards entered the studio to record “The People’s Limousine,” a song they had co-written and would release as a single.

The two were a match in ambition and aesthetic, with Burnett subsequently producing a series of Costello’s records off and on over the decades to follow, starting with 1986’s King of America. That album found Costello embracing his predilection for the singular sounds of the United States that had long captivated the British artist. Burnett teamed him with James Burton, Ray Brown, Earl Palmer, Ron Tutt, Jerry Scheff, Jim Keltner and other renowned players for an affecting statement from a transplant with bountiful roots. The new six-disc box set King of America & Other Realms, which came out in November, supplements the triumph of that studio effort with demos, live recordings and complementary tracks.

A few weeks after that release, Audible debuted The True Story of the Coward Brothers, a new comedic audio series scripted by Costello and directed by Christopher Guest. The all-star cast also includes Harry Shearer, Rhea Seehorn, Edward Hibbert, Stephen Root and Kathreen Khavari. A 20-track soundtrack album, The Coward Brothers, accompanied the three-part series.

The True Story of the Coward Brothers is a show within a show. Sterling Lockhart, who is voiced by Shearer, hosts a radio program that presents the conflicting, conflicted tales of Henry and Howard Coward. In the conversation that follows, their counterparts share their own intertwined but far less twisted yarns.

While the two of you shared musical affinities from the get-go, can you recall what led you to take that relationship to the next level and work together in the studio on King of America?

ELVIS COSTELLO: I think that upon meeting T Bone, I came to the recognition that I had committed to recording the songs I had most recently written in a style that really didn’t suit those songs.

With the benefit of hindsight, by the time we got to the Goodbye Cruel World record, the same producers who had been exactly right for Punch the Clock had a method of recording that was completely at odds with the new songs. So we had to spend a lot of time bending songs out of shape in order to fit in. That was a communal and joint decision. I’m not blaming them, the failures of that record were all my choices—the wrong band, the wrong songs, the wrong studio. Everything was wrong about it.

Then I discovered that those songs could belong to me again when I went out and just played them. But I also recognized that I was not addressing the stories I had in mind as clearly as I could. So I quickly wrote the songs which make up King of America.

It was at that point that I met T Bone and our alliance as T Bone Burnett and Elvis Costello and Henry and Howard Coward began. I think something he said very early on was to play with reference to the lyric. Some of my favorite saxophonists— Ben Webster, Lester Young, Coleman Hawkins—play with reference to the lyric as much as the harmony and the melody. They’re telling the story.

I had written narrative songs. Sometimes those narratives were to illustrate something I was feeling personally, like the truth of “Brilliant Mistake” or “American Without Tears.” Songs like “Indoor Fireworks,” “Poisoned Rose” and “I’ll Wear It Proudly” were setting it right out with unadorned language.

T Bone taught me how to face that and he helped in the sense of choosing the musicians who were most sympathetic for that way of recording at that moment.

T BONE BURNETT: I thought the songs were really good. There was a timelessness to them and it all started with that. One of the things I also realized early on was how deeply Elvis was into American music. I would say Elvis knows more about American music than anyone I know. I think that him coming and working strictly in an American music genre was powerful and I think he’s proved that over and over since then.

EC: Of course, during my very beginnings in recording, it was disguised from people because of the fashions of the day. I would say that most people didn’t know who played on my first album. They naturally assumed it was the band that they first saw me performing with, which wasn’t the case. The musicians that played on my first record were a Marin County band [Clover].

If you listen to the way the Attractions were playing those songs, by the time we got to El Mocambo in early ‘78 [for a live radio broadcast later released as an album] some of the songs were a third faster. There was that urgency—the aggression and attack of the Attractions, which was very persuasive to people. But the one thing it lost was the swing. You can’t really play swing music at that tempo. I know that when we did a benefit performance years later with the remaining members of Clover and Pete Thomas on drums, I couldn’t believe that the tempos in which he kicked off those songs were the correct tempos from the recording.

With King of America, we had to learn how to rein back some of the aggression that had worked wonderfully well with the early Attractions records to allow other elements of the music to come through.

It was still another discovery to work with these musicians—to work with Jerry Scheff, Jim Keltner and Ronnie Tutt and to have James Burton as a foil, who was not playing behind my voice but playing in the holes in between the voice. He was playing counterpoint to my melody. He was also playing guitar solos, of which there were hardly any on my first five records. There had been a few melodic interludes on things, but not what you would call guitar solos, which is obviously what James does. It was thrilling to be in close proximity with him when he was doing things like “The Big Light.”

TB: It’s a different kind of thrill. I saw the Attractions in Boston on the first tour, and it was completely exhilarating. It was the most energetic show I’d probably ever seen at the time, but all of that intensity has changed into a more internalized intensity.

EC: I don’t think you necessarily have to choose one or the other, though. I wouldn’t argue with the way Nick Lowe oversaw those first five records and then Blood & Chocolate, the record that succeeded King of America. But then on Goodbye Cruel World, the record that preceded this one, I chose the wrong approach for the group of songs I had. Maybe I didn’t even have enough songs of consequence to merit making a record.

Whereas with King of America, I had more than an album’s worth of songs. The odd thing was that when we handed it in initially, they didn’t want it, so they had us record “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” After hearing everything I’d written, they essentially asked, “Can’t you just write a good song that the radio will play?”

It was that level of insult but that’s because radio was already ceding its independence to programmers who were telling the radio stations what they should be playing to satisfy the desires of advertisers. There were fewer and fewer independent radio stations. So we went back in and cut “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” which was a fair version of that song, but it wasn’t a song I would’ve ever thought of cutting. I don’t even know whether it was it my idea to cut it.

TB: I think it was my idea because we were feeling so misunderstood.

EC: Here we were with brushes on a snare and double basses at a time when you’d hear these sledgehammer kind of drums on the radio. The closest we could get was this song, which I did have affection for, but then, irony of irony, I lost my voice on the eve of the session. So it didn’t matter that we’d recorded it because nobody could recognize me.

TB: These songs were so internal and so generous that I didn’t want to put a fancy jacket on them. I didn’t want to put rhinestones on them or try to dress them up.

T Bone, when we spoke around the release of your album The Other Side, you described your production ethos. You mentioned the need for empathy and hearing with the artist’s ears. Can you recall how this applied to King of America?

TB: I began hearing this material when we were on the road, and it was all being done solo and acoustically. So I got to know these songs in that intimate way, and I didn’t want to lose that intimacy in the record production. This is something that Elvis and I talked about.

I’d been working with Lenny Waronker as my mentor for some time, and he had taught me how to make a record that could get on the radio, which I hadn’t known at all, but I was also feeling very constricted by it. So with this material, it was coming from such an open, honest place that I wanted to stay in that place. So as I was listening, I was listening to make sure nothing got in front of that.

I feel like we were learning a lot from each other during this time and I learned a lot more as we started Spike, which was the next record we did together.

EC: There was only one record in between from me [Blood & Chocolate]. You made the Dot record afterward [1986’s T Bone Burnett on the Dot label], which shared some of the same musicians. It had that same kind of intimacy and didn’t go for the other record making things that I think we both had a suspicion of.

The odd thing about it was that in ‘88, I went into work with Paul McCartney on co-writing some songs and I was encouraging him to go toward this very strict way of recording. But then as we began recording together and co-producing some of these songs, it didn’t work at all because it wasn’t true to the way he was hearing them. He wanted to hear them more developed.

By then, we had started Spike, which was about as wide-screen as you could get. It was the exact opposite of King of America. We allowed ourselves almost anything that could be imagined. So we began in Dublin with Irish musicians and then went to New Orleans and worked with Allen Toussaint and the Dirty Dozen Brass Band. Then we went to Los Angeles and worked with all the musicians that played on the record there, and then we went back to London and recorded with Paul McCartney and Chrissie Hynde.

TB: But nevertheless, the same principle applied to Spike.

EC: Well, it was casting wasn’t it?

TB: That and we didn’t let anything get in the way of the song. The sort of tendency that you had with Goodbye Cruel World and I had with Proof Through the Night where the record production took over at some point. I think through doing King of America and doing the Dot record, we both were able to reenter the other world in a way that we didn’t allow the production to overtake the song.

EC: I had that experience the other night, when I went to hear the playback of Bob Neuwirth’s record. There’s a new remix of Bob Neuwirth’s first record, which came out on Asylum in ‘74. It’s a record where there are millions of guests. When you pick up the sleeve, you go, “Oh, I want to hear this. Look who’s on here.” [The roster includes Kris Kristofferson, Roger McGuinn, Don Everly, Cass Elliot, Rita Coolidge and many others.] But when you put the record on, the musicians are all too loud. I don’t know how it was mixed that way, but now it’s been mixed very sensitively and it’s been stripped back so that the good musical parts can be comprehended and, most important, the songs can be heard. Bob’s voice can be heard and the clarity of the writing comes through. It’s a familiar flaw of records from that time when people thought more is more is more. But it’s really not.

T Bone also produced Peter Case’s self-titled record around the same time as King of America, which is a very spare and beautiful album.

TB: Yes, we applied a lot of those same ideas. Although, again, it’s a matter of listening to the songs and being responsive.

EC: I remember hearing Peter Case sing “I Shook His Hand,” which is on that record, when we played together right after King of America.

T Bone had also done Los Lobos’ How Will The Wolf Survive?, which definitely feeds into this. I sometimes sang “A Matter of Time” around then and I suggested David [Hidalgo] could sing the harmony on “Lovable.”

TB: In a way, How Will The Wolf Survive? was a prototype for King of America. It was an American record. I think of all of this music as American music, whether it’s blues, jazz, country music, hillbilly music or mountain music. That’s the melting pot where people from all over the world came and listened to each other and made harmony together. I think one of the strengths of King of America is there were people from the jazz world, the hillbilly world, the rock-and-roll world. It was homogenous.

Thinking of the Coward Brothers, when you recorded “The People’s Limousine,” did you have any expectation that it might be something more than a fun one-off?

TB: I thought it was a fun one-off. I don’t recall any talk of doing an album or that sort of stuff.

EC: The European tour it commemorates is also detailed in T Bone’s song “Euromad,” which tells the dark side of that tour. “The People’s Limousine” was a surreal take on our time in Italy. Then the B-side was a Leon Payne song, “They’ll Never Take Her Love From Me.” That was recorded with Ronnie Tutt, David Miner and Stephen Bruton, which gave me a little insight into what it would be like to have that kind of accompaniment.

Bear in mind, on my very first session in Nashville—although it was the Attractions rhythm section, the pedal-steel player was Pete Drake. We cut “He’s Got You,” a Hank Cochran song that was “She’s Got You” when Patsy and Loretta each sang it, and “I’ll Take Care of You,” the Bobby “Blue” Bland song.

So my intention had always been to find that place in the road where all this music meets. I think you hear that in King of America. You hear it in “Poisoned Rose,” where having Earl Palmer on drums and Ray Brown on bass takes it into a world of jazz and references rhythm and blues as much as country. But the feeling is the same.

That’s one of the reasons I wanted to tell the story that I anthologized and annotated in the Other Realms part of this package. It includes an essay I wrote and the overall intention was to relate my understanding of this music, coming to it as an outsider, and how these messages from a long time ago— and in some cases more recently—educated me to the soul of music that I didn’t grow up with. This was particularly country music, but also a lot of R&B things, where we only had some compilation records with a few of these artists and then I got to America where I could buy a whole album by Joe Tex or somebody like that.

These songs that we performed at the Albert Hall alongside the King of America songs were my selections from what I call the Real American Songbook, the one that includes Willie Dixon, Waylon Jennings, Jesse Winchester, Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham, Allen Toussaint, Dave Bartholomew, Sonny Boy Williamson and Mose Allison. Those last people I mentioned come from the very cities that I got to record in through different circumstances, such as Yoko asking me to do “Walking on Thin Ice” and getting to meet Allen for the first time. I went back there in ‘88 to record “Deep Dark Truthful Mirror,” building my friendship with the Dirty Dozen Brass Band.

Of course, it’s not as if T Bone and I didn’t do anything together in the interim. There were cameos by the Cowards in our alliance as songwriters throughout a lot of this period when T Bone was a producer and a producer of music for film. I contributed to The Big Lebowski. We wrote “The Scarlet Tide” for Cold Mountain.

We did other projects that interwove all these things, and eventually it came time to record again in an unadorned way, which was Secret, Profane & Sugarcane, by which point I had returned to narrative songwriting.

Some of it was in service of an opera that I’d begun to write about Hans Christian Andersen and P.T. Barnum, which sounds like an idea [Robert] Hunter would have. I would have loved to hear his version of P.T. Barnum meeting Hans Christian Andersen in a fairytale.

Then we went and transposed those songs for string band players. It was a pretty serious combination of musicians—like one of Lionel Hampton’s bands—and pretty special to have Jerry Douglas, Stuart Duncan, Mike Compton and Dennis Crouch all in a band together with Jeff Taylor and Jim Lauderdale.

You mentioned Ray Brown. In the accompanying essay, you describe how prior to recording “Poisoned Rose,” he said, “Nobody play any ideas.” How did you receive that?

EC: I think it was really liberating, as I remember. We had conceived it with the bass introduction and just Ray and I in the first verse. There’s got to be some anxiety when you’re thinking, ‘This is the man who accompanied his wife Ella Fitzgerald.’ So that was a quality of vocal production he was more readily used to.

Of course, he didn’t record that many records with vocalists. He is on lots of records where there are vocalists, but most of his work as a jazz musician is playing in ensembles, whether they be bebop records in the ‘40s or playing with Oscar Peterson. They’re playing instrumental music predominantly, but nevertheless, he understood accompaniment of the voice very well. I think it was just nerves on my part but that disarmed me a little bit. It disarmed us all.

TB: I wouldn’t say that everybody was intimidated, but Ray had everyone’s attention.

EC: He was a big man, he was used to being a bandleader and he was a commanding presence. There’s a fantastic cassette that I hope Diana [Krall] won’t mind me mentioning of her taking a lesson with him when she was like 20. You can hear him cajole a young pianist. She went on to record with him and she regards him as a mentor. Often with the musicians coming from England, they were trying to supersede the thing that went before. But here was this tremendous energy to will the person to play as well as they could. That’s what I had in miniature with this brief experience. She had a little bit more of that. They got to make a whole album together, which would be a dream come true.

But all of these alliances for King of America were beyond my imagining. I didn’t believe you could just call up and get James Burton. I thought it was like getting into an Ivy League university or something. I assumed there had to be some form you had to fill out to get James Burton. I didn’t know you just called him and said, “Would you like to play on my record?” It seemed inconceivable because he was a name printed on record sleeves that I’d listened to over and over—not necessarily Ricky Nelson and Elvis Presley, to be honest. I was most thrilled that he was the guitar player from “The Return of the Grievous Angel” or the guitar player in the first Hot Band lineup. These were the records that I had really listened to in detail. I was aware of his other work and I was aware of the videos of him playing with Elvis, and that was all great, but that wasn’t music I’d listened to for pleasure. That music just existed.

TB: He was also on all the Merle Haggard records.

EC: I helped induct him into the Country Music Hall of Fame a few weeks back. I was one of the surprise performers along with Emmylou Harris, Rodney Crowell, Vince Gill and Keith Richards. It was an extraordinary afternoon, but the most wonderful thing about it was listening to what was almost a gasp, as they listed James’ credits. They were just ridiculous.

TB: I think one of the other things Ray was saying to the younger musicians was just play this song—play the lyric, play the melody.

EC: Even when you write the song, you can still get in your own way. I can testify to that.

Is it a coincidence that King of America & Other Realms and this Coward Brothers project are coming out at the same time? Did one prompt the other in any way?

EC: As we were working toward the King of America set, I had already written the scripts for the Coward Brothers, hoping to put it in a fable form that we could perform. We were tremendously fortunate to have Christopher Guest as our director because his ear for dialect and for nuance kept us both very much within the written characters. We had fun with the delivery of it, and all of the actors really have delivered their voices so well, that it isn’t as if you need pictures to see it. I also think one of the good things about this coming out on Audible is that there is a context for all of these songs to come into existence.

We did hold the release back a little while because of the bolt of inspiration that hit Henry Coward, which meant that T Bone Burnett had the record The Other Side, and I would not have wanted there to be a second more before it was shared with the world. The Cowards are out there all the time in the background, in the middle distance, in the ether, in the water system. They’re floating around in there all the time, like chemicals that we can’t get rid of.

TB: And accusing us of stealing all their songs.

EC: So before they started saying that about the songs on The Other Side, that record had to be released. When you have a record so beautiful and open-hearted as The Other Side, I feel its moment to be heard is exactly when it is completed. The Cowards have waited this long, so they can just become even more embittered by the slight delay that it took.

Speaking of The Other Side, it includes “Come Back (When You Go Away),” which you told me you’d written for Ringo. I didn’t realize that he’d also recorded it until the announcement of his forthcoming album, which you produced. Can you talk about his version on Look Up?

TB: The version I did was just guitar, slide and Dobro. It’s a little trio. He did a very full-blown version of it with Lucius adding some beautiful counter melodies and some answers. Stuart Duncan’s on it. Ringo whistles on it—he’s a beautiful whistler, actually. So he does a more finished version of it, I would say.

Did you write the songs for The Other Side and Look Up at the same time you were writing for the Coward Brothers?

TB: Yeah, it actually started when we were doing the Coward Brothers. I wrote that song “Always” and started singing in a different voice. I started being Henry Coward, so I was just in a very different place and I started singing softer and more in my chest with that. Elvis and Chris were very supportive of that and gave me the courage, I guess, to continue in that voice.

Then when Ringo asked me to write a song for him, I wrote, “Come Back (When You Go Away)” and then he asked me to write another one, and I haven’t stopped writing since. Elvis said I hit a vein and I’m still writing constantly. But I wrote all the Ringo songs and all the songs for The Other Side essentially in the same period of time.

Did the two of you create the music after the script was written?

EC: Yes, the script was written during the emergency when we were all locked away. For the first part of the prohibitions of travel and gathering, I was on Vancouver Island in a remote cabin. I just sat out there in the spring and wrote out what we had talked about doing as a cartoon about 15 years ago. I found the treatment of that, and I thought there were some good elements that we had always riffed on, and I just wrote it as a script.

Writing a completely imagined history of our other selves seems to make as much sense as the rest of it. If you’d told me that I was ever going to meet half the people that are involved in the King of America & Other Realms set, I wouldn’t have believed you— whether it be Ray Brown, Allen Toussaint, Emmylou Harris, Kris Kristofferson or Paul McCartney, not to mention the individual instrumentalists and soloists. If you look at the continuity with the Imposters and our friendship for 40 years, that’s a tremendously fortunate life.

If you read the note very carefully, then you can see that I allude to knowing when I’m leaving—not this earth because nobody knows that. But I know when I’m leaving the stage. I know the time and I know the place, and I know what I have to do before then.

I’ve done some of it and some of it’s still to be done. This is part of it. The Cowards’ story lines up with that feeling of needing to know the way out.

I tell my sons, you can go and protest anything you want, but when you go into the square to protest, remember a few things. There are other people that disagree with you who may have violent intentions. The second is that the police are not your friends. And the third is you must always know the way out. That last thing is the key thing for everybody in performance—you must always know the way out. The Cowards never knew any of these things.

What you’ve just said is rather weighty, although much of the Cowards’ story is lighter in tone and laden with wordplay.

EC: Without giving anything away for the readers, it begins in a satiric note and it actually becomes more emotional as the story goes on. I think that’s what I want to convey to people who are not sure whether they want to spend time with this. On its face, it may just seem like a lighthearted satire on rock-and-roll, which has been done very well, not least of all by Mr. Guest. But the reason I think he was generous enough to be our director is I remember him expressing surprise when he read the second and third episodes because the way that the story continued was not predicted by the end of the first act. That allowed the Cowards to write some songs which are about consequential things.

So to swing back, King of America & Other Realms and the Coward Brothers project speak to one another irrespective of when either was released.

EC: I think the timing of the Coward Brothers has ended up explaining more about our friendship. It also made the case even greater for the anthology of the Other Realms part of the new release because this is not just something we did 40 years ago. This is something we’ve been doing ever since.

The King of America & Other Realms exists for people other than the people that know these records. It’s there to invite people into a body of work and a relationship and not just with Henry and I. It’s my great good fortune to have written with Allen Toussaint, to have sung with Emmylou Harris for 25 years and Lucinda Williams for about the same amount of time. To have been introduced to Kris Kristofferson and then for Roseanne Cash and myself to have written a song with him, which is one of the last ones on there. Even “That Day Is Done,” from just prior to when we made Spike, is represented. It’s recorded with the Fairfield Four and Larry Knechtel is playing piano. These are records that I’m very proud of, and it’s about the story that winds through all of these things. It’s something of a fable in itself.