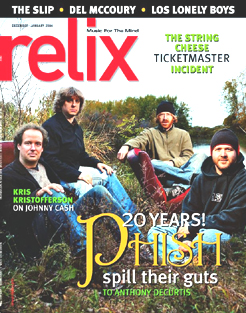

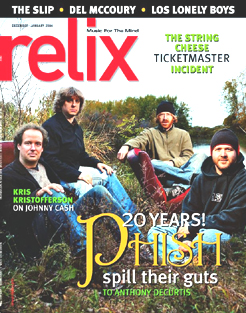

Destiny Found? Phish Come Clean (Relix Revisited)

With Phish taking Halloween off this year and thus no fevered anticipation regarding their costume in the days leading up to October 31, we figured we’d share this cover story from December 2003 for those of you hankering for some Phish. On Halloween, we’ll run a piece from this era in which the band members name their favorite albums.

Trey Anastasio is sitting at the bar in a hotel restaurant not far from The Barn, the bucolic Vermont studio that serves as something like Phish’s recording headquarters, rehearsal space and spiritual home. He’d been working at The Barn all day that Saturday – and from his wild-eyed, amped-up, giggling demeanor, you wouldn’t be blamed for thinking that he’d been born in that idyllic space surrounded by instruments and equipment, fallen incurably in love with music and simply never left. He’d spent much of the afternoon working on a woozy piece inspired by his tapes of one of his young daughters banging on the piano keyboard as she sat on his lap. A mini-orchestra will be arriving in a few days to record it. “It’s very possible that all this stuff will end up on the new Phish album,” he declared with a mad glint in his eyes. Cabin fever had set deeply in.

Now, however, he was calmly eating a sandwich platter and nursing a beer. On the television set above the bar, the Florida Marlins are in the process of eliminating the San Francisco Giants in the National League’s western division playoffs. This being New England in early October, the (inevitably heartbreaking) fate of the Boston Red Sox is on everyone’s mind, including Anastasio’s. “I had this fantasy,” he leans over and says, barely able to contain his glee, “of posting on our website that I had had a dream that Babe Ruth appeared to me and told me that the curse of the Bambino was finally over, and the Red Sox were finally going to win the World Series this year!” Did he actually have that dream? “No!” he says, slapping the bar in emphasis. “Not at all. But I figure if they lost, everybody would just forget that I ever posted it. But if they won, people would think I was some kind of prophet!”

Anastasio obviously finds the idea of perpetrating a hoax like that hilarious – the master of the revels exulting in his Trickster role. But his fabricated dream is also a spoof on an image of the guitarist that is all too real for many Phish fans, and that Anastasio often has felt the daunting responsibility to live up to. As Phish approaches its twentieth anniversary this December and attempts to chart the course of its future after a thrilling reunion year, Anastasio deeply feels the need to keep that notion of himself in clear perspective. He’s successful part of the time.

“Trey’s not reading articles about the band so much any more,” Phish keyboardist Page McConnell had said at lunch in downtown Burlington earlier that day. “He would stress out about it when he would read things and felt that he was misrepresented. He’d take stuff really hard. He worries about what people think.”

Worrying about what people think and freeing himself of what he perceives as the expectations of others was a large part of the reason why Anastasio initiated the so-called “hiatus” in October 2000 that put Phish on hold for two years and called its very future into question. “It was hard for me to feel resentment from people who were our fans, our friends or even members of the band that I was busting this thing up for my own personal reasons,” Anastasio had said that day at The Barn. “I mean, all I’d done my whole life was work on Phish. I loved it and I wanted it to be healthy. But I remember thinking during the period around Billy Breathes, that I’m leading this thing and I want everybody in the band to be happy, but I didn’t want to create resentment, so I stepped back. In 1996 when we were on tour I stopped playing lead guitar. It was like, okay, well, somebody else do it then, somebody else lead it. I don’t need to do this.”

His eyes searched the loft space at The Barn, and then he continued to speak. “Maybe I worried about it too much,” he said, “‘Is everybody happy? Are you writing enough?’ The interpersonal relationships – feeling that responsibility, that was the biggest thing for me. I felt a great amount of pressure for years: What would happen if Phish broke up? What do people have to fall back on? So it somehow became important for me to sustain it, and I got confused. It became a problem for me, because I didn’t want to resent Phish. But I don’t think it’s healthy for any of us to have our whole lives based around the band.”

His feeling entrapped by that responsibility – and his resentment of it – extended to his role as the Pied Piper of the jamband scene. “I was thinking about this interview for Relix, which is now the voice of the jamband scene,” he says, "People have asked me so many times: How do you feel about being labeled a jamband? I never knew how to answer that, because it’s irrelevant, right? It’s just music.

“But then this morning,” he goes on, “as I was thinking about this interview, I thought, ‘It’s unhealthy.’ People who are in this scene should think about something: Music can’t have a scene. It’s completely wrong. I believe that music is a language that gives you a glimpse of the divine. It’s much, much bigger than me or anybody. It’s everything. But you can’t get to the truth any way other than by being yourself. And as soon as you have a scene, you put boundaries on what your path is going to be. Any musician who ever did anything that touched people did it because it was original. With the healthiest respect for all the people in it, if you’re following music, you’re going to have a problem with any kind of scene. It’s a balancing act.”

Eventually it became a balancing act with some dangerous risks. “Nobody ever talks about this around Phish,” Anastasio says, "but drugs had infiltrated our world – and me. I don’t want to point my finger at that, because the problems had started a long time before. It was about losing myself, losing track of who I really am.

“With all four of us I saw different ways of avoiding the inevitable need that you have as a human being, especially as you’re getting close to 40, to look at who you really are in the midst of this whirlwind. So drugs became an easy way to put off facing yourself. It was like, Well, I don’t have to think about that for one more night.”

He laughs at the futile effort to avoid hard truths. “It all starts to sound like such a cliché,” he admits about his rock star agonistes laments, “but it’s shocking when you see yourself and all your friends falling into that trap. Everybody was going through stuff in one way or another, whether they want to admit it or not. It was the stuff of exhaustion. The public persona of me is as this really happy guy, but somehow I ended up fucking miserable and just soldiering on. Finally I just said, I’ve got to do something about this, or it’s going to do me in. It really started to feel like that.”

Hence the hiatus, and hence the reunion. The twentieth anniversary celebration that Phish has scheduled for December 2 at the Fleet Center in Boston – marking the date of the band’s first gig, though McConnell would not join until two years later – is not merely a nostalgic indulgence, but a genuinely new beginning. A raggedly beautiful new album, Round Room, a New Year’s Eve show at New York’s Madison Square Garden and two brief tours earlier this year reconnected the band and its tribe of devoted fans, and demonstrated a recharged sense of purpose. Still, while the mere fact that the hiatus was over may have been enough to satisfy the most undiscriminating wing of the Phish nation, that was hardly enough for the band members themselves. To paraphrase the Rolling Stones, Anastasio wasn’t the only one with mixed emotions. Everyone else needed to come to grips with, as bassist Mike Gordon puts it, being “the guy from Phish.”

“It’s so easy to get stuck,” Gordon says as he lounges on a couch in his Manhattan apartment, “either in terms of your image, or your situation, which has gotten locked in since you were eighteen. You start to ask yourself, Am I even a human, or am I just the bass player from Phish? And even in terms of being in Phish – in the jamband community that’s cool, but over the years a lot of the music industry in general has thought that we’re a stupid band.”

He’s just beginning to build up steam. “And I’m the guy who writes the songs that have been silly, or tongue-in-cheek, over the years,” he continues. “I make these movies that are off-the-wall and weird. So am I just a huge joke? I know I have deep feelings about all kinds of things, so is it a joke that I’m doing such light-hearted stuff? So there’s a line, and you can teeter-totter on it very easily: You can see yourself as a successful, creative person, or as a joke. Being ‘the guy from Phish’ can be like that. It’s the most respectable or most stupid thing that you can be.”

The realities of life in the band weren’t always merry either. “Over the years there have been times when I’ve been butting heads with Trey,” McConnell says. “Or Mike and Trey were. And I suppose those conflicts still do happen. But you have to have some methods of resolving those things. You have to appreciate the greater good and realize that there is something we get from Phish that we don’t get anywhere else. Trey, Mike and I doing our own bands has helped us see how unique Phish is.”

As Jon Fishman sits in his home outside Burlington, with relatives coming and going because his girlfriend, Briar, has given birth to their second child just a few days earlier – on Anastasio’s thirty-ninth birthday, in fact – he grows visibly moved when he discusses his relationship with his bandmates. “To me, the band is my ideal blueprint for how I would like to communicate with my girlfriend or my wife or my kids,” he says. “In that way it’s been a school… I’m sorry, I’m getting emotional right now, I can’t even …” He collects himself, then continues. “The hiatus gave us a chance,” he says, “to appreciate what Phish brought to all of our lives, and to appreciate the opportunity that we have going forward.”

That sense of renewed appreciation, of having dodged a bullet that could have split the band up forever, is a recurring theme in conversations with all four men. The collective opinion is that the band’s 2003 shows displayed a vigor and excitement that the group had felt only intermittently in its performances leading up to the hiatus. The band’s eyes now squarely focus on the future. “This first year back from the hiatus,” McConnell says, “we’ve been settling back in. We’re just now at a point where we’re ending the comeback. Now it’s time to look ahead. Okay, we’re back, but where are we?”

Perhaps the most significant developments in the world of Phish are the various side projects that band members have undertaken, which in a variety of complicated ways, have eased the interactions of the band members with each other. Gordon collaborated with guitarist Leo Kottke, released a solo album, Inside In, this fall, assembled a band and took it on the road. McConnell’s combo, Vida Blue, has released two albums, and, after Phish’s New Year’s Eve stint in Miami, that band and Jazz Mandolin Project, in which Fishman occasionally plays drums, will do a string of East Coast dates together in January. Fishman’s own band, Pork Tornado, also released an album and toured last year. And, needless to say, Anastasio, a self-described “workaholic,” continues to juggle his nine-piece band, Oysterhead and a seemingly infinite number of other existing and potential gigs. “My mind doesn’t always think of Phish when I write music,” he says. “I’m so happy now that everybody has an outlet outside of Phish, so that I don’t have to feel uncomfortable having outlets outside of Phish.”

“Look, Trey shits music,” Fishman explains bluntly. “You can’t tell someone, Only write five songs, not ten a day. So let him be Trey and write his ass off. And Mike can be Mike and write his one song and hover over it until it’s done. Despite our extremely different personalities, we all value each other’s creative input. I’m a sideman in Jazz Mandolin Project, but I tested my leadership abilities with Pork Tornado. In some ways I failed miserably, and in some ways I succeeded. Ultimately, I discovered that I don’t like having to call the shots.”

Gordon and McConnell also say that fronting their own bands has made them more appreciative of the load Anastasio has been carrying in Phish all these years. “It’s been a great experience, and I’ve learned so much from it,” McConnell says about Vida Blue. “But among other things I’ve learned that I really enjoy my role in Phish. Phish is as much a democracy as any band out there, but Trey definitely is Trey.” He laughs, then continues. “I’m more comfortable now with the skills and leadership qualities that he brings, and that he’s so prolific,” he says. “That’s something I’ve had to address in myself with Vida Blue. There’s a lot of responsibility involved in leading a band – writing the songs, setting up the set lists. To put it simply, I found that I enjoy just playing the piano.”

Attempting to comprehend the members of Phish and their deeply intertwined personal relationships is an effort to defeat linear thought. Things mean exactly what they mean, as well as their precise opposite. A two-year separation is really a strategy designed to help keep the band together. A dizzying number of ancillary projects both consumes each of the four men’s time and energy, and reinvigorates their enthusiasm for Phish. It’s a Zen exercise that parallels the intricate twists and turns in the band’s music and its now two-decades-long career.

It’s important to keep those blurring and blending contradictions and corroborations in mind as Anastasio explains how keeping almost entirely to himself on last summer’s Phish tour was really an expression of how deeply he was communicating with his three comrades and the band’s audience. “I absolutely loved that tour, and the rest of the band did too,” he says, as the late-afternoon sky begins to darken outside the windows of The Barn. "It was very satisfying. I completely isolated myself. I had my own car at the end of every show. I didn’t even go on the bus. I didn’t socialize. After the shows, I went straight back to my room. I started meditating – stuff I’d never done before. I just focused. I decided, I’m on this tour to play music, and that’s all I’m going to do. And that was it – right through It! At It, I had a lock on my trailer. I chatted a little bit with people, but I didn’t really talk to anybody. On that tour, we’d be on stage, and I’d be thinking, ‘I’m playing.’ Then we’d play the last note, and when the note was over, I’d think, ‘Now, I’m walking.’ ‘Now, I’m in the car.’ ‘Now, I’m eating.’ It was really peaceful. So when you’re playing, you’re right there.

“I want to achieve a feeling that this is all worthwhile for some reason,” he continues. “That it’s about something bigger than the four of us. We want to connect deeper with our audience.”

That something bigger and the source of that connection, needless to say, is music – and the spiritual realm beyond, to which music provides a portal. Anastasio believes that, finally, is the only reason Phish or any band should stay together. On that point ,everyone agrees. “The hiatus was good,” says Gordon, “because, even though our tours were great up until then, in my opinion, something about the creative process had gotten pretty far from our college days when we’d be in somebody’s dorm room jamming for five hours and writing original songs just because we could. It was music for music’s sake – not for a tour, not for an album. We had lost some of that childlike wonder, and that’s what we wanted back.”

Anastasio even managed to work out some of his own doubts. He describes how a friend put a Phish CD on in the car as they were driving home from a Red Hot Chili Peppers Show. “He put on ‘Esther,’ and he said, ‘This is really weird, unique music,’” Anastasio recalls. "Normally I would hear that song and beat myself up – ‘Oh, this is stupid. It’s horrible.’ But what I heard that night was the fact that, at that point in time, there was zero pressure on us, and out of that came something unique. Even the fact that I stopped writing lyrics, which I used to do – part of the reason for that, if I’m honest with myself, was a feeling of embarrassment that had slowly built up.

“You have to get to the point of not caring what anyone thinks. It’s like, ‘Play “Tweezer,” play “Tweezer,” play “Tweezer” !’ I’d go, ‘It’s a stupid song, I don’t want to play ‘Tweezer’ – it sucks. ’ Then you go on tour, like this summer, you start playing it, and you find yourself just laughing – ‘Oh, I forgot – I love playing this song!’ I was so worried about it, that I forgot whether I wanted to play it or not."

After celebrating the band’s 20th anniversary, and performing the New Year’s Eve shows in Florida, Phish will return to the studio to make a new album with producer Tchad Blake, who has worked with Los Lobos and Pearl Jam, among many other groups. The album is likely to come out next summer, with some touring to follow. But nothing is carved in stone. Perhaps the most important lesson the members of Phish took from the hiatus is that they can make their own rules. Record when they like. Tour when they like. Participate in other projects when they like. And, though this does not seem to have occurred to any of them yet, do nothing when they like. The demands of the band and its audience no longer feel so overwhelming, because the individual members now understand that they can accept, reject or redefine those demands as they need to.

“Now being a little older and more mature,” Fishman says, “we have all the tools to really be a Superbowl contender. Not in an egotistical way, but I do have a gut feeling that Phish is going to be a really good band now. The potential of where we can go musically is… I can’t even conceive of it now. I have never felt better about the band. If people liked the summer tour, I can’t wait until they see us again. The peak years are coming!”

“We’ve put Phish into its proper place,” Anastasio says. “It’s not going to take over our lives. It’s not everything. We all have other things we’re involved in. But all of that is a tool to embrace the playing more. I felt much more appreciative of Phish on the last tour than I have in years. I just couldn’t believe how lucky we are to have this. I had to get away from it to realize that.”

He gathers his thoughts and focuses himself. “At this point in my life it’s pretty simple, even though we’ve been talking about all these grand ideas,” he concludes. "I can get my musical satisfaction sitting at the piano and writing. And I drive my kids to school, and I love to see them in their ballet classes, or whatever. So going to Cleveland or sitting in a hotel in Cincinnati for two days is not appealing to me. It was when I was in my twenties, but now it’s a big distraction from my family life. Why would I want to leave the heaven that’s in my living room? Is it worth it for those three hours on stage?

“On the last tour, it clearly was. I loved it. So I can’t wait to go on tour with Phish now. I can’t wait. I wish it was tomorrow. We were focused on that thing that’s bigger than we are. And as long as it stays like that, it will stay worth it.”