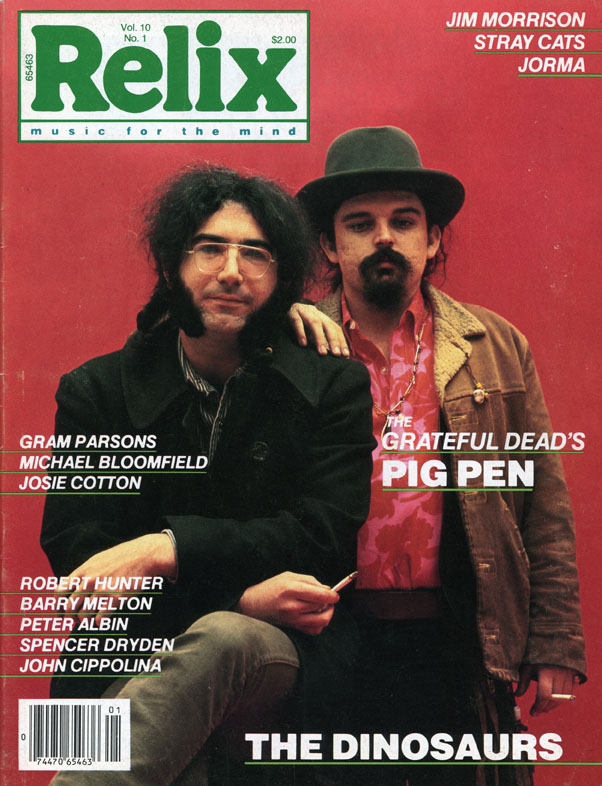

Death Don’t Have No Mercy: Pigpen, Ten Years Gone (Relix Revisited)

Today in 1973, Ron McKernan, better known as Pigpen, the founding keyboardist and de facto original frontman for the Grateful Dead, passed away at the age of 27. In Pigpen’s memory, we offer a remembrance from the February 1983 issue of Relix, where editor Jeff Tamarkin looks back on the musician’s impact and unique timeline with the Grateful Dead a decade after his passing. Along with the piece, enjoy an audio compilation and photo slideshow of over four-and-a-half hours of Pigpen-led tunes (via YouTube user Phrostington), including “Mr. Charlie,” “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl,” “In the Midnight Hour,” “Good Lovin'” and “Turn On Your Lovelight,” among others:

One day in February 1973, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan got out of bed in his apartment in Corte Madera, California, where he’d recently been spending most of his time, and walked over to his piano. He pushed the record button on his tape recorder and started playin a slow, bluesy dirge. His voice was shot, withered away like the rest of him. He sang:

“Look over yonder, tell me what do you see?

Ten thousand people lookin’ after me.

I may be famous or I may be no one,

But in the end all of our races are run.

Don’t make my race run in vain.”

He threw in a couple of fills on the keyboard and continued:

“Seems like there’s no tomorrow.

Seems like all my yesterdays were filled with pain.

There’s nothin’ but darkness tomorrow.”

It was the saddest song he had ever sung. Although Pigpen’s thing was the blues, his was never the blues of death and loneliness, but the blues of whisky and women. He loved them both too much for his own good. In the end, it was the whisky and women that did him in. He continued:

“Don’t make me live in this pain no longer.

You know I’m getting weaker, not stronger.”

It was actually a song for a girl that had walked out on him, but it was also Pig’s goodbye song to himself.

“I’ll get by somehow.

Maybe not tomorrow, but somehow…

I didn’t realize what was happenin’

To my life…

I’m gone,

Goodbye, so long.”

Goodbye, so long, it was to be. Pigpen didn’t get by, not tomorrow, not ever. On March 8, 1973, a month after he put down that song—one of a number of tunes he’d been writing for a solo album that was never to be on tape, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan got up and out of that same bed, walked a few feet and died. He put his yesterdays filled with pain behind him.

Pigpen’s race was run, but today, 10 years after the Grateful Dead lost their soul man, we have to wonder: did Pigpen run his race in vain?

There are times that it would seem so. The name McKernan does not get mentioned in the same breath as Morrison, Hendrix, Joplin, Presley, Holly or Lennon when we talk about the rock-and-roll greats that have left us. But perhaps it should be. Pigpen should not have died in vain, and his contributions should be recognized. Pigpen was not just the best blues singer to come out of the San Francisco scene, he was one of the best white blues singers rock-and-roll has ever known. Whereas Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield, Steve Winwood, Steve Miller, John Mayall and he rest had to study the blues, to figure out what the black man meant in his music, Pigpen only had to live it—and he did. Pig was more than just a singer in a band—he was one of the most fascinating personalities ever to find his way into the rock-and-roll history books. And the fact that he sang with the Grateful Dead is another whole story in itself—Pigpen gave that the band an element of coolness they never would’ve had without him. It is debatable whether there would even have been a Grateful Dead without him. But then again, it made absolutely perfect sense that he should be part of the Dead. Who else would have taken him? Who else would’ve understood him? Who else would’ve let him get away with being the way he was?

The Grateful Dead, with Pigpen singing, comprised the perfect American band for the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Think about it: with Pig up front, you had a blues-singing country boy fronting a rocking folk band with jazz sensibilities. Can you get more American than that?

Pigpen brought the music of black America to the Dead. Whereas Jerry Garcia brought folk and bluegrass, Bob Weir brought pure angry teenaged rock-and-roll, Phil Lesh brought electronics, jazz and weirdness, and Bill Kreutzmann brought incredibly flowing, sharp rhythms (doubley incredible when Mickey Hart was around), Pigpen brought James Brown, Lightnin’ Hopkins, the Coasters, Elmore James, Jimmy Reed, Wilson Pickett, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf, Otis Redding, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, the Olympics, Willie Dixon, Chuck Willis and Chuck Berry. It was often said that Pigpen was a black man in white man’s skin, and it was not a lie; this wasn’t another case of white man’s guilt—Pigpen was simply a blues-breathing kind of guy.

Ron McKernan was born either in 1945 or 1946, depending on which account you read—in either case, it was apparently on September 8. His father was a rhythm and blues disc jockey and the boy, who lived in the industrial area in and around San Bruno, California, south of San Francisco, took an early liking to the kind of grits his papa was laying down on the turntable. He picked up the harmonica and learned to play it the same way those cats did.

He learned to play the piano and the organ. He learned to play the guitar. He learned to go by feeling in his singing and not technique; he learned to project and to incite a crowd. Ron was playing acoustic and electric solo guitar in the coffee houses near the colleges in his area. He became sort of a local hero, this white kid who could play and sing black. Folk music was enjoying a revival in the early ‘60s and the blues was a part of it; college types dug that down-to-earth pure American sound the same way they dug the bluegrass music that local groups like the Sleepy Hollow Hog Stompers and later, Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions—both featuring a young banjoist in his early 20s named Jerry Garcia—were playing.

It wasn’t long before this teenaged blues junkie with the slicked back hair and the thin mustache and the voice that totally ignored key and pitch was discovered by Garcia and his friends, and they let him sit in and do a blues every so often. Pigpen, as the young McKernan kid had become known, didn’t mind: for him it was a chance to play his Leadbelly tunes to someone other than the old black dudes that would hang out in the sleazy bars where he used to play. And the bluegrass guys didn’t mind; for them it was a chance to have a bona fide oddball conversation piece adding some guts to their all-American, wholesome kind of hillbilly sound.

It was 1962 or ’63 when they met, and by 1964 the whole thing had blossomed into a full-grown scene. Pig’s friend Jorma Kaukonen was around, playing his blues. Guys like David Freiberg and Robert Hunter were around, as were David Nelson, Peter Albin and an accomplished musician named Phil Lesh. They played every place from clubs like the Boar’s Head and the Tangent to local Jewish Community Centers, in various configurations. And they began attracting a weird bunch of people: literary types like Ken Kesey; Hell’s Angels; a kid guitar player named Bob Weir. Somethin’ was happenin’. Dope became less of a secret and more of a lifestyle. And there was this new shit called LSD. Everybody started taking it and talking about its mystical, “mind-expanding” properties. It became a way of life for Kesey and his crowd. Garcia was a big fan of the drug. It seemed everyone was getting stoneder and stoneder. Except Pigpen, that is. The blues kid didn’t need nothing’ but his guitar and harp and a bottle of cheap rotgut wine.

1965 was the year of electricity. Garcia, Lesh, Weir, Kreutzmann and Pigpen—a bunch of misfits if there ever was one—picked up electric instruments and started jamming around the peninsula, playing a weird conglomerate of go-go pop, electric folk-rock, excruciating noise and interminably long blues tunes. They all became phenomenal musicians, ‘cept Pig, whose Farfisa playing was kind of circus music-like, but cool. They became the musical accompaniment for Kesey’s tripping parties, the Acid Tests. They got weirder and weirder. Them before they knew what had hit them, they got bigger and bigger. They changed their name, not, as Garcia had suggested, to the Mythical Ethical Icicle Tricycle, but to the Grateful Dead, pulled out of a dictionary by Lesh. The misfits signed a recording contract, became famous, toured the U.S.

By 1968-’69, they had become the kings of San Fran psychedelia. But by then Pig’s position in the band became insecure. He wasn’t interested in their expanded trip music unless it was blues-based, and it was becoming less so. The Dead relegated Pig to congas and occasional vocals. Tom Constanten took over on the organ, playing an ethereal, classically-rooted sound Pig didn’t know from and didn’t care to know. The band was way out there (witness the Aoxomoxoa album) and Pig was out of place. He threatened to quit. Then, they changed their minds, and came back heavier than ever. Pig played his Hammond organ and loved it.

Pigpen fronting the Dead around 1970 was an experience beyond description. Standing at stage center in his cowboy hat, denims, black fuzz growing around his mouth—top, bottom, sides and down into a point below his chin—with his harmonica in his hands, Pigpen commanded attention. And he got it. No one in a hall sat when Pigpen walked out from the wings—sometimes eagerly, sometimes damming the others for calling him away from his comfortable backstage perch—and launched into one of his soul grooves. Whether it was a hell-raiser like Otis’s “Hard to Handle,” or the Rascal’s “Good Lovin’” or a stone solid hard blues like “Smokestack Lightnin’” or James Brown’s “It’s A Man’s Man’s World,” or a slow, cool blues like Slim Harpo’s “King Bee” or an acoustic version of Lightin’s “She’s Mine,” Pigpen was the focus of attention. He knew how to grab an audience and he did so in this band by providing an element of funkiness that the others didn’t have. His earthiness and their spacedness was the perfect combination—heaven and hell.

Pigpen got away with being raunchy and by doing so he added street-tough to the various images projected by the Dead. And he inspired the band, did he ever. The nature of his music by itself forced the group to play a different way. Blues and soul are more disciplined linear musics than the free-form music the Dead engaged in during “St. Stephen,” “Dark Star,” Cold, Rain And Snow,” “The Other One,” etc. The blues demanded that Garcia play more pronounced, solid, lyrical, chunkier lines on his guitar, almost taking the place of a horn section. It put Weir in the position of having to skip his usual flourishes and stick with strict rhythms. The drummers were forced almost to be stiff. And Phil Lesh, though he did what he could with the bass rhythms, was put in the all-important position of having to lay the path that the singer would follow. This they all did rather admirably, and their reward came during the breaks, when Pig stepped aside to let them “ride awhile.” Pig would sometimes play along with them on organ or harp, and although no one ever accused him of being a good musician, he played soulfully. But his playing was rudimentary in comparison.

The jams that came out of Pigpen’s song however, were often nothing less than physically and spiritually draining. Once let loose after a minutes of actually backing a vocalist, these improv-hungry musicians took off like a rocket. The jams that could be found in the mid-section of a “Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl,” “Easy Wind,” “Hard To Handle,” “Smokestack Lightnin’” or the tour-de-force of pigpen/Dead-dom, “Turn On Your Lovelight,” were easily some of the most sensational exhibitions of raw improvisational musicianship ever to emanate from a band working within a rock-and-roll framework. Pigpen made them work hard and they did.

Pig was also the clown prince of the Grateful Dead. He was a wise-ass and a showman in a band that purposely practiced anti-show biz attitudes. It was Pigpen who would get pissed off at a lousy sound system and tell the sound man that if he didn’t get the sound in shape real soon, Pig would proceed to “cut off your head and shit in it.” It was hardly a line one might expect from Jerry Garcia.

Or how about the immortal version of “Lovelight” from the Fillmore East in April 1971? Pig was fond of extending the song by inserting an ever-changing rap into the loose body of the tune. He would usually invite the guys in the audience to clap their hands, to “take your hands out of your pockets and stop playing pocket pool.” He liked to get people in the audience to act together and get it on together—Pig was a firm believer in sex and more sex, the nastier the better—and was known to suggest to audiences (for instance at Stonybrook, NY in October ’70) that they should “turn to your neighbor and say, ‘Let’s fuck.’” But in that April ’71 gig, the same one at which the Beach Boys walked out of nowhere and joined the Dead onstage for awhile, Pig did it up for real. He pulled two people out from the crowd and invited them onstage. He introduced them, and then he sent them off together. “Chris and Marcia have just made it!” he announced proudly, mission accomplished. And it wouldn’t be surprising if Chris and Marcia were still together today; such was Pigpen’s charisma.

It was around the time of those closing gigs at the Fillmores, however, that Pig’s life started taking a turn for the worse. I remember that the first and only time I ever met him was while waiting on line one afternoon for a front spot at general admission Dead concert—at the Manhattan Center in New York. About four in the afternoon, Pig came strolling by. “anybody know where the nearest bar is?” he drawled in that not-quite-Southern accent that you shouldn’t have if you’re from California unless you’re a white black man. We pointed across the street and he went in that direction, accompanied by his black girlfriend of the time. About two hours later Pig came strolling back, obviously stewed, A few of us talked to him for awhile about the latest Dead news: about the new riders, about Mickey Hart’s recent departure from the band and about wine—he was an expert on cheap wine and he liked to talk about it as much as he like to drink it. Then he walked in the theater. But I remember some people on line commenting that he didn’t look well.

A few weeks later, at the aforementioned Fillmore gigs, we waited around one night after the show for the band to leave. Pigpen came out first. He was still acting as wild as he had been an hour ago as he brought the show to an end with one of his rave-up show-closing bashes. He had his black girl on one arm and white one on the other. His cowboy hat was pulled down almost over his eyes—was he cross-eyed of was it the booze that made them look so screwed up?—and started walking quickly down Sixth Street toward Second Avenue. Suddenly he howled at the top of his lungs in this own inimitable outlaw-on-the-run style. It was light out and we—audience members—were ready to pass out for a few days; we were drained of energy. But Pig was still on the go. After the howl he shouted halfway down the block for a taxi, which stopped in its tracks to pick up this less-than-harmless-looking trio. And he was gone. That was the last time New York ever saw Pigpen in tip-top shape. He missed a good part of the East Coast tour in the fall of that year and didn’t sound up to par at the shows he did make. The reason the band gave for his absence was that pic was sick but he’d be back soon.

He was back in March 1972 to play the Academy of Music shows, one of them featuring the Dead serving as a backup band for the legendary rocker Bo Diddley. And he made it to Europe the next month, against his doc’s advice. He played his last gig with the Dead in June ’72 at the Hollywood Bowl. After that, there were few excuses the band could make. Although he had seemed well enough on the European tour in the spring, Pigpen McKernan was losing his grip in life. The doctors told him what he needed wasn’t good lovin’ but a lot of rest, no booze and lots of protein to put his decaying liver back together, He couldn’t do it, lost his will to live, and in March ’73 we got the news that Pigpen had died.

It didn’t seem all that much of a surprise when someone came ringing my doorbell that spring day to tell me what had happened. When this non-Deadhead friend casually mentioned that “A guy in the Grateful Dead died,” it didn’t trigger a mad dash for the radio to find out who it was. I knew who it was, and although I was a hardcore Deadhead at the time I wasn’t shocked. It was only a matter of time; most of the hardcores had long ago come to terms with the fact that we were probably never going to see Pig alive again.

And many of us knew that we’d never see the Grateful Dead quite as alive again, either, that the band which had given us the highest musical heights we’d ever known was going to lose a lot of its soul—and heart. Although Keith and Donna Godchaux had already been added to the band by the time Pig died, giving them a new direction, the experience of getting off on the Grateful Dead dropped a few levels in terms of the bliss factor when the group’s official mascot took the next Easy Wind out of town for good. No longer could we expect to be awakened from the psychedelic haze at their shows by the cowboy riding in for another shot of rhythm and blues, putting a smile on our faces while making our feet dance crazy rhythms. Pigpen was a big guy in life, but by listening to his work with the Dead, and recalling what he was like, he seems, 10 years after his liver gave in, even bigger in death. There will never be another one like him.

This article originally appeared in the February 1983 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.