Deadicated: Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey

“Bluegrass is a nice metaphor for how music can work as a group. In other words, bluegrass is a conversational music,” Jerry Garcia says in an archival video that will appear as part of a special exhibit at the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum in Owensboro, Ky. Such conversations are at the heart of Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey, which will open with a special celebration on March 28-30.

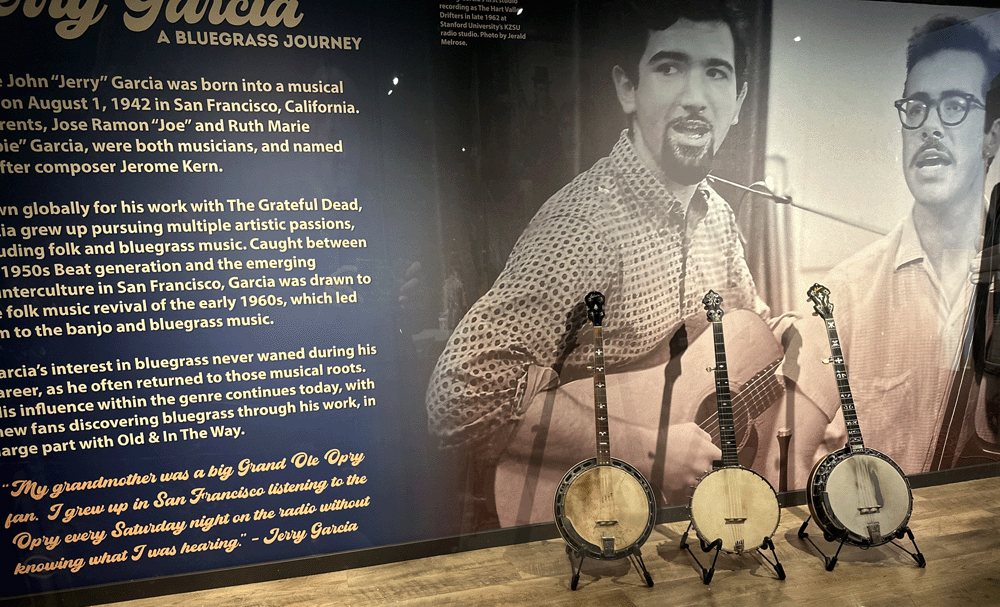

The exhibition explores Garcia’s early acoustic output, including his efforts as a banjo player who aspired to join Bill Monroe in the Blue Grass Boys. A 1,000-square-foot gallery will house the installation, which features a number of Garcia’s musical instruments, rare recordings and a variety of other artifacts, as well as series of taped interviews with David Nelson, David Grisman, Sandy Rothman, Peter Rowan, Sara Ruppenthal Katz, Carolyn “Mountain Girl” Garcia, Del McCoury, Billy Strings and others.

Carly Smith, the curator of the museum, notes, “This is not a Grateful Dead exhibit. We’re tracing his bluegrass career. From what I have learned from his family and early collaborators, he was completely obsessed with the banjo. He played it for hours, and he would be playing it while he was carrying on a conversation with you. The Before the Dead compilation is great because you can really hear how quickly he improved in just a few years as a teenager. Throughout his career he felt like he was a student who needed to practice his craft. Maybe that came from those early days learning the banjo— the Scruggs style, the threefingerpicking style.”

The initial commemorative weekend will feature music from Leftover Salmon with a number of special guests, including Peter Rowan, David Nelson, Ronnie McCoury, Eric Thompson and Pete Wernick. Sam Grisman Project will appear as well, and the festivities will include film screenings and panel discussions

While the opening has sold out in advance, Smith counsels, “The exhibit is going to be open for two years, and we are going to be doing a lot of additional programming around it. We’re located just two hours north of Nashville. We’re right on the riverfront and there are beautiful new hotels right next door to us. So I’d definitely encourage people to keep an eye out for future events that we’ll announce and be sure to come see us while the exhibit’s open.”

How familiar were you with Jerry Garcia or the Grateful Dead before working on this exhibit?

I would describe myself as a Deadhead since I was in middle school. I have older brothers and I bought Shakedown Street and American Beauty on cassette tape. That’s what I spent my money on when I was younger.

I wasn’t old enough to go see them until I was in high school. I grew up here in Kentucky and I bought tickets to see them at Deer Creek in ‘95. I had planned to see the second show and I thought, “Finally!” Unfortunately, they had the gate-crasher situation at the first show, so the second show, which was the one I was planning to attend, was canceled. I never got to see Jerry.

So I’ve always loved the Grateful Dead and when you pair that with what I’m doing with my profession, it’s been really inspiring. This has been a great project for me.

At what point did you come to appreciate his interest in bluegrass? Was it Old & In the Way?

While Old & In the Way was how a lot of people discovered it, for me, it was when The Pizza Tapes came out. [The Pizza Tapes collects two studio sessions with Garcia, Grisman and Tony Rice from 1993.] I was obsessed with it. It was this whole new world. Then I started going back and listening to Old & In the Way.

The thing I noticed is that, when he is playing guitar, I hear him as a banjo player. He has that bounce in his playing. At this point, I’m so familiar and versed with bluegrass music and the banjo that I can really hear it. He had such a unique tone when he was playing electric guitar with the Grateful Dead.

Another interesting point in terms of the exhibit is that the music of the Grateful Dead has been heavily explored within the bluegrass genre. It makes sense to a lot of bluegrass artists who are covering Grateful Dead songs in their setlists. That’s an easy transition for bluegrass artists.

In the video excerpts I’ve seen from the exhibit, Jacob Groopman also makes that point. He says that once he understood that Jerry was a banjo player, his guitar playing made more sense.

I’m so glad Jacob said that because, for me, that is spot on. My opinion is that if you have an ear that has heard a lot of banjo and bluegrass, you can pick that up pretty quickly when you go back and listen to the live performances or even the studio recordings.

Given your musical predilections, had you been contemplating this exhibit for a while?

I’ve been with the museum for almost 13 years and the idea has definitely been sitting there. Our core exhibit space is focused on the foundations of bluegrass— Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, The Stanley Brothers. But we also have what we call our temporary exhibits. That’s where we can explore these cool stories tied to the genre.

In 2018, we were fortunate to be able to move into a beautiful new building. We built a $15- million facility through some great local fundraising efforts. So we doubled our exhibit space and we had a thousand square feet of temporary exhibit galleries, along with a 450-seat theater.

It was the next year when we started journeying toward this exhibit. Jerry Garcia is an icon and we felt it would be really impactful to tell the story of his bluegrass roots.

Vince Herman and Leftover Salmon were here playing a show in our theater, and Cliff Seltzer, a good friend of Vince’s, was in town. They toured the museum and asked, “What’s the plan for this temporary gallery?” We had been open for four or five months, so that already had been on our mind, but after speaking with them, that’s when the ball really started rolling.

Of course, the pandemic sidelined us for a few years on this, but it really picked up again in 2021 and we received funding from the Daviess County Fiscal Court, which is our county government. Then it just took off from there.

Once you decided to move forward, what was the first artifact you sought out? Did you have a particular item in mind?

Instruments were going to be the main thing for us because that’s the tool. So we were just hoping to get one, maybe two, and we’ve ended up with 12. It’s been phenomenal that people are so generous to loan us these instruments for display. But that really cements the story, too— these spectacular instruments he owned. We don’t just have banjos, we have a mandolin of his. He was even scratching around on a fiddle, although we don’t have a fiddle of his. But it’s been wonderful. The instrument side of things really helps tell this story.

Jerry’s first wife, Sara Katz, has played a role in presenting that story. Can you talk about her contributions?

Sara is a wonderful lady. She has been just so giving and helped us make connections with other people.

She has a really unique perspective in terms of the time frame when they were together because that’s when he was bit by the bluegrass bug. She still has Jerry’s bluegrass album collection, which is full of Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, the Osborne Brothers, Jim & Jesse.

She’s been an incredible resource and she’s so accessible. Earlier this week, I had a question about identifying someone in a photo, and she knew the answer and got right back to me.

It was a pleasure to have her sit down with us when we went to film her for an interview.

I think what really opened the doors for us was that we were exploring the bluegrass side of things, which hasn’t been done all that many times. We learned from people in his inner circle that he would travel with a banjo when he was going to Hawaii. Things like that just really affirmed we were on the right track.

Dennis McNally is someone else who helped us get this project off the ground and had connections with the right people.

David Nelson’s been great to work with and has such great stories to tell. They’d go down to LA to see shows at the Ash Grove. David talks about the time that he and Jerry drove to the Ash Grove to see Bill Monroe, and David spoke with Bill about learning how to play the mandolin. They were going down there quite a bit.

How about Sandy Rothman, who made the trip across the country with Jerry, hoping that Bill Monroe would invite them to join his band?

Sandy’s been an incredible resource and was one of the biggest connections for us early on. He’s so knowledgeable and was an early collaborator with Jerry. A big part of the exhibit is exploring that trip they took to the East Coast because they were kind of starved for live bluegrass in the Bay Area.

But that was the idea for that journey, just as you described it. Then when they got there, they chickened out. From what I’ve heard, Bill Monroe could be an intimidating figure to some of these younger guys. Sandy, of course, would go on to be a Blue Grass Boy in Bill’s band.

One cool thing that I picked up on through that story is they took a Wollensak reel-to-reel recorder. They were taping these shows and the Grand Ole Opry on the radio. If I could ask Jerry something about that, it’d be whether that was an early indicator of allowing tapers at the Grateful Dead shows. What’s also really great is Sandy Rothman still has some of those reels. They’ve been digitized and they’re going to be part of the exhibit.

We even have a Corvair. It’s a replica, painted the same color. So that’ll be in the exhibit space to really emphasize that trip.

This feels like the right time for this exhibit, which to my mind, might have stirred up some controversy in the bluegrass community a number of years ago. Does that sound accurate to you?

I think on the surface you could point to that, but I also think it’s great to see an evolution within the music. It’s expanded. If you’re close-minded about keeping it the same, you’re not going to attract as many people to keep it alive.

While some people might think that this is just a new thing that has happened lately with Billy Strings and The Infamous Stringdusters, it was already occurring. New Grass Revival with Sam Bush, and later Béla Fleck when he joined, were doing some really interesting things in the ‘70s and ‘80s. But I also find that bluegrass artists, no matter how far out there they may go, are well-versed on the foundational work of Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin and people like that. They can play that stylistically; they’re just adding their own takes on it.

I do think the timing, though, is great—the way bluegrass is more recognizable. Billy Strings and Chris Thile just performed on CBS Saturday Morning. So I think it’s at a healthy point.

When Sam Bush talks about New Grass Revival, he’ll point out that some people crossed their arms or just walked away when they played at bluegrass festivals, refusing to accept what they were doing.

They called them chair snappers. [Laughs.] The interesting thing he’ll say is that the artists themselves were accepting. It just took a little time for the fans to get it.

Carlton Haney, who started the first multi-day bluegrass festival in ‘65, explained it really well. He called it the Long Hairs and the Short Hairs. But it’s about the music. If you can play, you can play.

What can people expect at the opening weekend?

Our opening weekend celebration will be filled with a lot of music. Sam Grisman Project is kicking things off Thursday night, and then on Friday and Saturday night we’ll have Leftover Salmon, who are going to serve as our house band exploring Garcia’s bluegrass repertoire with special guests. Peter Rowan, who played with Old & in The Way, will be up there. David Nelson will be on hand. Ronnie McCoury is going to participate. We’ll have a lot of people participating, including some surprises. So the musical component is going to be great.

Another cool thing that I’m excited about is we’re going to have some panel discussions that will allow us to really dig in. We’ll have some of Garcia’s early collaborators and some of his family up there exploring his bluegrass roots with moderators. So there’s going to be that component during the day.

Also, our theater where the concerts will be taking place can serve as a movie theater, so we’re going to have some documentary films running as well. Grateful Dawg explores his long relationship with David Grisman. Festival Express is something else we’d like to show, as well as episode one of Long Strange Trip.

The way we envision it is you’re going to be on campus with us for three days. After the last panel, we’ll have a free concert lounge in the lobby of the museum. So we want to generate a lot of excitement and energy by keeping things going throughout the day and into the night.

For those who will be visiting the exhibit, is there something that, for one reason or another, you wouldn’t want them to miss?

Something that I love is we have a 1904 Martin guitar that was loaned to us by Mountain Girl. It’s an acoustic guitar, and it doesn’t have a pickguard on it, so it’s very worn in one area. She said that he was writing a lot of his music at home on that guitar, which I think is just such a cool connection. If you go back, there’s a Grateful Dead film that was filmed in England in 1970, and there’s a sequence where Garcia, Phil Lesh and Bob Weir are rehearsing “Candyman” and it’s the same guitar. I was able to make that identification because it didn’t have the pickguard and it had the same wear on it.

I like the personal stories that we can connect to some of these artifacts.

Sara saved three shirts that she made herself for her “Cosmic Cowboy” in the early ‘60s. Those are just amazing to see, particularly because Jerry was known for wearing his black T-shirts for most of his career.

Another cool thing about this exhibit is we’re able to pull a lot of things from our existing collections that are part of the story. For instance, Jerry produced that album Pistol Packin’ Mama. Don Reno, who was on the album, is in our Hall of Fame and I have one of his suits, which I estimate is from the ‘50s, along with a Stetson cowboy hat and his acoustic guitar.

There are plenty of things like that. I have an Earl Scruggs shirt. Tex Logan, who wrote the song “Diamond Joe,” was friends with David Nelson and the New Riders, and I have his boots, fiddle and hat. So there are connecting points that are really interesting.

I have Roland White’s mandolin, which Clarence played with the Kentucky Colonels while Roland White was in the service. That’s who Jerry and Sandy Rothman followed out of California on their trip—the Kentucky Colonels. So that mandolin will go on display.

I have a letter from Robert Hunter to Jesse McReynolds congratulating him on his tribute album [Songs of the Grateful Dead].

I also have Robert Hunter’s suede jacket and one of his Western shirts. He’s a big part of that early story, so we’ll have some Robert Hunter items as well, although those are on loan.

I have Sam Bush’s first fiddle. New Grass Revival’s last show was on New Year’s Eve ‘89 opening for the Grateful Dead.

It’s been so wonderful to have these “aha” moments where things intersect. A goal for a museum is to be able to showcase the collections, so it’s not just Garcia artifacts. We have so many other things from bluegrass history that are connected. It all just reinforces that this is an interesting and important story to tell.