Deadicated: Howard Wales, A Previously Unpublished Interview (On Jerry Garcia, Jimi Hendrix and the Lost Live Tapes)

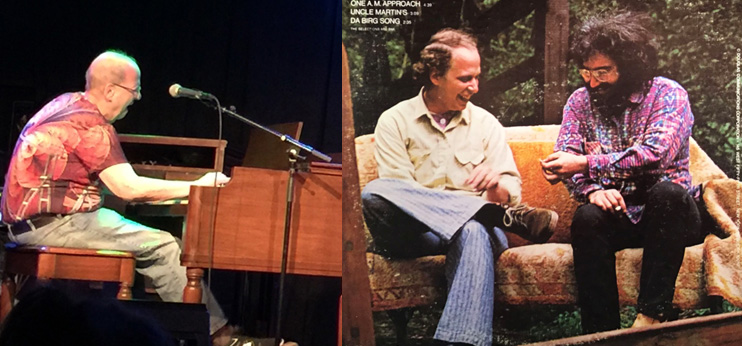

Howard Wales live at Sweetwater (Robison Godlove); Back cover of Hooteroll

***

On Dec. 7, 2020, keyboard player Howard Wales passed away at age 77.

Wales’ career began at 18 and included stints with an array of artists like James Brown, Lonnie Mack and The Four Tops. In addition, he toured and recorded as a member of the late-‘60s psychedelic blues act A.B. Skhy and released eight solo albums, starting with his dazzling debut, Rendezvous with the Sun.

Still, Wales may be best known for his collaborations with Jerry Garcia. These date back to a late-‘60s jam session at San Francisco club the Matrix and later yielded their 1971 record Hooteroll, as well as a 1972 tour. Wales also appeared on the Grateful Dead’s American Beauty album and the band later considered him for a keyboard slot.

As Garcia once said of Wales: “Playing with Howard was so outside…Howard did more for my ears than anybody that I’ve ever played with because he was so extended and so different.”

The following conversation with Wales took place in conjunction with an April 2017 Hooteroll tribute show at The Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, N.Y., led by Joe Russo.

While the interview focused primarily on Hooteroll and its antecedents, Wales’ comments about Rendezvous also serve as a fine introduction to his musical ethos: “We had a blast making it and it’s a timeless piece; it will never expire. It will go all the way till the end because that album was so far ahead of the curve. You need the right headspace to deal with it. If you’re not out of the box, man, how the hell are you going to listen to it? But you see, all the albums are different. Each one has a different concept and all of the music is original. All of it is real and all of it is original. You know original, right? We’re not past that yet, are we?”

When you were starting out, who were your inspirations on keys?

My specialty is the Hammond B3. I got into that when I was about 24-25 years old. I got a spinet organ to start with and then got into the console organ. But as a B3 player, I really looked up to people like Jimmy Smith and Jimmy McGriff.

I also wanted to set myself apart from being a bebop organ player. So that put me in a place where my individuality got in there. I wanted to be well-rounded, bring my thing to it and remain out of the box.

You were in your mid-20s when you started on the B3 but, by then, you had already been gigging for a few years, including a stretch backing some notable acts. How did that come about?

I took piano lessons for a few years as a kid, learning classical music but, at some point, I couldn’t deal with my piano teacher anymore. So she exited, but I realized that I liked the keys, so I’d take my allowance and buy sheet music for these different pop songs. I was into it but I had no idea if I was going to be professional.

Then when I was 18, I made a trip to Chicago [from Milwaukee] to see what I could discover. I ended up playing with Robby & the Troubadours on Rush Street for about a year. I did a couple of other things with some other groups, earning my stripes to the point where I was road-worthy.

From there, I crossed the border and found my way to Toronto, where I did some playing with Ronnie Hawkins on the Wurlitzer electric piano. That’s where I met the members of The Band and some other people. I was there for a while and then made my way back to the Midwest where I teamed up with Roger “Jellyroll” Troy. He was a bass player and a really great vocalist who sounded like a blend of Ray Charles and Bobby “Blue” Bland.

We formed a group that ended backing up artists like The Four Tops, The Coasters and Little Anthony and the Imperials.

This was also the era when you played with Lonnie Mack.

That’s right. Lonnie was turned on to me by Jellyroll in Cincinnati. That’s also how I ended up doing some recordings with Freddie King at King Studios. I also met James Brown there and I ended up doing a few gigs with him much later in my life.

James Brown was someone who exerted rigorous control as a bandleader. Given that your live performance approach emphasizes improvisation and variance from gig to gig, that must have been an uneasy fit.

That’s an understatement. It only lasted four gigs. There was a little bit of a compromise that was not good.

I’ll tell you something though: My belief is that to be a full player, you have to do the good and the bad. I did all kinds of weird stuff. I backed up a gal named Sally Rand, the fan dancer. She was very famous, man. She danced around with these special things she carried but she was otherwise naked out on the stage. I had to play and back her up on piano—you can imagine what a gig that was.

But if you do all the different stuff, it gives you a fuller understanding of music itself. So, particularly when you’re starting out, if you can do all sorts of things—the good, the not-so-good and the great—you can develop a nice comprehension of what’s happening on all these different trips.

Back to Lonnie, can you talk about playing with him?

We never recorded together but I played with him for about a year and a half. At that time, I had an old underpowered Volkswagen bus and I was lugging around a B3 and a Leslie or two. I remember he was always asking me to get another vehicle. [Laughs.]

Lonnie had such a great band with the horns. He had his own unique sound, too. That should be the goal, to be original. So many people don’t know who the hell they are to start with, so they can’t figure out how to be original—but not Lonnie. He played through a Magnatone Stereo amp and he had this tremolo thing on a Flying V Gibson guitar. He had his own style and I can’t say enough about that. If you listen to his album The Wham of That Memphis Man!, you can hear it.

At what point did you end up in Texas?

That came next. It’s where I met my old friend Martin Fierro, who passed away about eight or nine years ago [in 2008]. I met him in El Paso, Texas, when I was working in an all-black club called the IT club. It’s where I also met Steve Miller. This was 1965 and I was doing an organ duo with a B3. Martin came in one night; I remember he was wearing this brown sports coat and said, “You guys burn! Can I sit in?” So I let him sit in because there was so much room given that it was just a duo. There was an instant connection. He sat in every night after that. We’d have other people, too.

We lost touch for a little while but, when I came to San Francisco a few years later, I ran into Martin and he ended up getting me a job at a tortilla factory.

A couple of years after your Hooteroll project, Martin teamed up with Jerry in Legion of Mary. Did you introduce the two of them?

No, I’m pretty sure that Martin had already introduced himself. That’s the kind of guy he was, just really open and friendly. I also imagine Jerry appreciated what he had to say, both as a musician and as a human being. For Jerry, there was no segmentation; it was all entwined.

Back to your journey, was San Francisco the next stop after El Paso?

Not quite. I found my way to San Diego and then up to Seattle. I was in the U District, living on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and jam sessions. There were some really good players up there, but I’d heard that something was happening in San Francisco so I decided to check it out.

So I went down there and the first thing I saw was The Electric Flag at The Fillmore with Buddy Miles and Mike Bloomfield. That’s when I said to myself: “This place is happening” and I decided to stay. [Laughs.]

In my opinion, it was a real Renaissance period. There was a scene there that valued creativity and originality. People wanted to hear what you had to say, rather than what they wanted you to say. It was a scene that I don’t think will ever be repeated.

You became part of that scene quickly, through A.B. Skhy. How did that happen?

I have to give credit to Bill Graham on a lot of levels. He opened up people’s ears and exposed them to so much more than what they had been accustomed to. Bill encouraged experimentation by the musicians onstage and by the people in the audience. He presented so much more than rock or pop. For instance, he put B.B. King and Albert King on bills and turned on so many people to them.

He was also really good to A.B. Skhy. The guys had come out from Wisconsin and I met them on Haight Street. Pretty soon, we were playing places like the Straight Theater, the old Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom. We were a blues band but Bill liked us, so he had us open for Albert King, The Who, Woody Herman and lots of others. We were a great opening band because we never got caught up in our own trip. We knew we were there to warm up the audience for the main act. Bill appreciated that.

I know that Bill could be difficult, particularly if people made things difficult for him. But I have nothing but good feelings about him.

During this time, Hendrix sat in with A.B. Skhy. Did that happen through Bill?

It happened in Los Angeles, although it wouldn’t surprise me if he had a hand in it or put in a good word. I also imagine that Jimi saw our name on one of those concert posters Bill made for his shows. We were playing on Sunset [at the Whisky a Go Go] when Hendrix came down and sat in with us. That definitely helped focus some attention on us. [In the Nov. 9, 1968, issue of Melody Maker, Hendrix identified a couple acts “who could make it big in the near future” including “a groovy blues group called A.B. Skhy, which is dynamite.”]

We signed with MGM Records and our record [1969’s A.B. Skhy] came out. I had a tune on there, “Camel Back” that they released as a single. Two weeks out, it made it to No. 100 on the Billboard charts with a bullet and it was starting to get airplay across the country. But then someone took over MGM and people were fired, which ended the plans for a full-page ad in Billboard. It’s one of those sad but inevitable music business stories you hear about.

On a more positive note, let’s talk about a project that has not been so fleeting. The legacy of Hooteroll certainly endures to the present. How did your association with Jerry Garcia come about?

I was asked to lead a jam session on Monday nights at the Matrix. This was 1969 or ‘70. It was a really small place— it probably held 90 people and everyone was sitting down. There was no dancing, so it ended up being cerebral and contemplative.

It was perfect for me because I’m from the school of jamming. I don’t like to rehearse anything. What I prefer to do is improvisational and purely in the moment. A lot of people came down who could hang with that, including Steve Miller, Elvin Bishop and Harvey Mandel.

One day, Jerry showed up and that’s how I met him. Then he kept coming back every week. I think what appealed to him is what appealed to me— the spontaneous aspect of it. He was so open, nothing scared him and he loved to learn. Like me, he also appreciated the spiritual side of it. For a while, it felt like everyone who showed up both onstage and in the audience was on the same page.

Eventually, it became such a big scene that it changed. There were too many people that I didn’t think should be playing and some of them started to be rude and just jumped onstage. I got fed up with it, so I transported after a period of time and gave it to somebody else.

But before that happened, Alan Douglas came in and saw what we were doing. He really appreciated it and so he was the one who made Hooteroll happen. [Douglas produced the album and issued it on his own Douglas Records.]

During that same era, you recorded three songs on the Grateful Dead’s American Beauty album. What are your memories of that?

A lot of the memory banks were eviscerated during that period. [Laughs.] Back in those days, the cloud of smoke was heavy. We were pretty young and had a “no holds barred” attitude, so remembering particulars of certain things sometimes can be hard to bring up.

I can tell you that I thought it was the best album that the Grateful Dead ever made. I thought the music had a good flavor to it. I imagine that other people would probably say different things, but that’s my opinion and not just because I played on it.

I’ve read about your audition for the Grateful Dead in interviews with a few different band members. What they all seemed to say, in the most respectful of ways, was that you were a little too far out for them.

I think that was part of it, for sure. But even though we jammed together I wasn’t totally convinced that it was the right path for me. There are a lot of aspects to it beyond just the music onstage. I was supposed to go to Europe with them at some point but then that didn’t happen because I don’t sing. At least, that’s what they told me. Of course, I sing with my fingers.

Back to Hooteroll, what are your memories of recording that record?

Brother, let me tell you something. If you had been there, you would have been lost in the cloud of smoke. [Laughs.]

I do remember the important stuff and, by that, I mean my relationship with Jerry. He was a fellow explorer. Like me, he believed there are no boundaries in music and he felt comfortable going places that other people would have a problem with.

We were also really good friends and continued to be really good friends for years. It wasn’t just about the music; it was all-inclusive. I loved hanging out with him when we weren’t playing. We’d sit around and talk about a lot of cool stuff.

One of your Matrix shows with Jerry, John Kahn and Bill Vitt was released back in 1998 as volume one of the Side Trips series. Were more of those jam sessions recorded?

The Matrix wasn’t very big but, when you walked in, there was a tiny alcove where the owner had set up a recording system, either a two-track or four-track. So we knew we were being recorded but we didn’t think too much about it.

He made recordings of everyone who played there. I can’t recall how that one surfaced. I know there’s another one in the vault with Harvey Mandel, rather than Jerry, but I imagine there are others out there somewhere.

Side Trips was released after Jerry had passed away but he had been such an advocate for it that, even though he wasn’t here when it came out, I got a good deal and I feel like he was looking after me.

I’ve heard a lot of interesting comments about that album—both pro and against it. Everybody takes in what they want to hear, so a few people hated it and some thought it was the greatest thing since sliced bread. But I guess that’s to be expected in a situation like that where we’re doing everything with no rehearsing and it all comes down to chemistry. People are fascinated by that because we live in a world where everything is so pre[1]rehearsed and pre-done.

How did the 1972 tour come about?

That was because of Jerry. He wanted to shine some light on me. That’s the kind of person he was. Jerry would give his right hand for you. He was a great soul and he really cared.

The bass player on that tour was my friend Jellyroll. He passed away when he was only in his 40s after bypass surgery. He was such a talented musician and a true jammer. The drummer was Jerry Love from Cincinnati and we also had Jimmy Vincent on guitar. He later played on Rendezvous with me.

We were all of one mind on that tour—doing some far-out stuff. It’s something of a blur but we were doing it all in the moment and playing to people who were drawn to music that was fresh and original.

I’ve heard the FM broadcast from the Boston show. Do any other recordings exist?

I have a copy of the Boston Symphony Hall broadcast with less radio interference, which can be a little distracting. But I also have a lost show from the tour. The performances are great. It does have a couple of small technical difficulties but, on an overall level, I think it’s easy to look past that because Jerry played some of the best blues I ever heard him play on that tour.

But, like I said, that tour was basically a blur. It was something like eight gigs, and we probably got two hours of sleep in that time. By the time that we finished, we were about ready to be delivered to the emergency room.

But it was a great tour, man. You know why? Because none of it was rehearsed. That blows people’s mind waves. [Laughs.]

You have to be out of the box enough to play like that. But some people can do it because they’re jammers, and jammers have no fear.