Bob Marley: The Lion’s Last Roar

Today on the 72nd anniversary of Bob Marley’s birth, we revisit this feature on his final performance.

Lord, I’ve got to keep on moving

Lord, I’ve got to get on down

Lord, I’ve got to keep on grooving

Where I can’t be found

– “Keep on Moving”

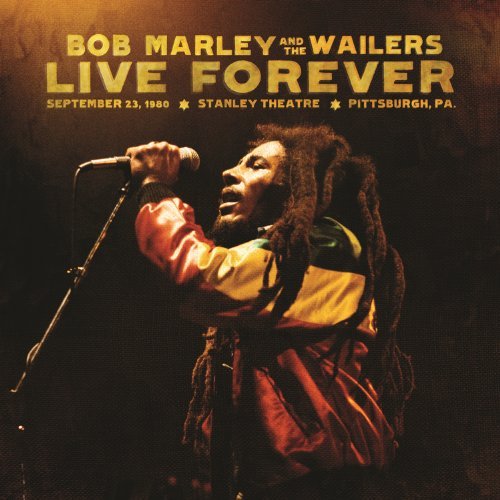

On September 23, 1980, Bob Marley took the stage at The Stanley Theatre in Pittsburgh, and played the longest known concert of his life – a three-encore epic that culminated with a six and a half-minute rendition of “Get Up, Stand Up.” Months earlier, tickets sold out immediately for the gig, and when Marley and the Wailers finally arrived, the capacity crowd of 3,500 got everything they wanted, and more than they even understood. Having spent that night watching from the wings, peering out at the frenzied, packed house, owner/promoter and fervent Marley fan Rich Engler remembers being spellbound. “It was spectacular. I can’t even put into words how good it was. They just lit it up.”

Yet, it’s a performance that the surviving Wailers can barely remember. To put it simply, “Pittsburgh was a blur,” notes guitarist Al Anderson. And for good reason. Unbeknownst to Engler and the Pittsburgh fans who kept calling Marley and the company back for encore after encore, the band and entourage were on pins and needles the whole time – their eyes fixed on their leader, worried that he might at any moment suffer a seizure or faint onstage.

Two days earlier in New York, Marley collapsed during a morning jog in Central Park. As his body was “freezing up” and pain was shooting through his neck, he fell into the arms of friend Alan “Skill” Cole, who carried him back to hotel they were staying at, the Essex House. Although he recovered in a few hours, a neurologist examined Marley the next day and gave him just two weeks to live. “They came in and said, ‘Bob, you’re in a lot of trouble and you need help immediately,’” says Anderson, who was there for the diagnosis, alongside Cole and manager Danny Sims. “It was like time started moving in the other direction.”

Marley ignored the prognosis, just as he had done during the past five years – ever since the steel spike of another player’s cleat during a soccer match had pierced the big toe on his right foot. In 1975, that toe became infected. By 1977, when his toenail fell off, doctors told him that he needed an amputation – that it was a matter of life or death. Again, the Rastaman ignored them, suffocating the toe in boots he wore onstage and offstage, believing Jah Rastafari would cure him. They told him that he needed to go for check-ups every three months, which he blew off. Now, the melanoma that started in his toe had infested his entire body. At just 35 years old, Bob Marley had a terminal brain tumor.

As the doctor was diagnosing Bob, the rest of the entourage – including his wife Rita – continued on to Pittsburgh, unaware of just how sick he was. Meanwhile, Marley’s booking agent phoned Engler and informed him that although the band was en route, Marley may not leave New York. That night, in her hotel room in Pittsburgh, Rita had an ominous dream in which a sickly, bald Bob spoke to her through iron bars.

Back at the Essex House, Marley paid a visit to longtime Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who was living in a suite on the top floor of the hotel. Largely responsible for Marley’s international stardom in myriad ways, Blackwell had long avoided taking a posed photograph with Marley, worried that the circulation of such an image wasn’t in keeping with his artist’s rebel persona, and, frankly, because he deemed it kind of corny. In yet another one of the eerie moments surrounding this final week of the Uprising tour – the first and only week of the ill-fated U.S. leg of that tour – Marley reportedly suggested that they pose for a photograph before he left town.

The next morning, Rita told her fellow I-Threes backup singers, Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt, about her premonition, and called Bob at the Essex House, where the phone was passed around to his remaining entourage and business people. She eventually hung up irritated, learning only that Bob was not feeling well. She didn’t learn of the severity of his condition until his arrival in Pittsburgh, hours later, when he told her about the tumor. “I felt as if my heart had left my body,” she wrote in her autobiography. Outraged, she went to Griffiths and Mowatt, then to Sims, trying desperately to cancel the show. She phoned Blackwell and Bob’s lawyer and doctors in Miami. Alan enraged her even more by telling her “the doctor said he might as well do the tour, because he’s going to die anyway.”

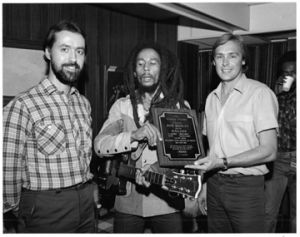

Stanley Theater promoters Pat Dicesare and Rick Engler present Marley with a plaque to mark the show’s quick sellout

When Jody Wenig, Marley’s agent, phoned Engler that morning, he remained mum about the tumor, stressing only that Engler should check with Marley as soon as he arrived. Even with him in the building, they were not guaranteeing a performance. It would be up to Marley. When he saw some band members filtering by his office, the promoter headed to the dressing room where Marley was resting on a couch. “I could see that he did not look well,” recalls Engler. “His face was drawn and he looked very, very, very tired. He looked worn out, but I just thought he had a cold. I said, ‘How you feeling?’ He goes, ‘No good, mon. Very, very tired. Not well at all.’ I said, ‘Are you going to play?’ And he said, ‘I probably shouldn’t but I need to do it. I need to do it for my band, they need the money. We’re here, we’re gonna play.’ I said, ‘That’s great, but if you can’t do it, don’t. Don’t push it.’ He said, ‘We’re gonna do it, no problem.’”

While Marley told Engler that he wasn’t going to sound check, he not only joined his bandmates onstage, but he did so for what would also prove to be their longest and most memorable sound check – one in which the proud singer touchingly communicated to his friends what he was feeling without actually having to look them in the eye and say it. Uncharacteristically, says Mowatt, he didn’t speak a word into the mic, sat on the drum riser when not singing and only signaled to bandleader/bassist Aston “Family Man” Barrett when he wanted a level tweaked.

“Normally, we would do like one or two songs,” she says, “but this was more like a rehearsal.” Without interacting with the band at all, for a half-hour, the troubled Tuff Gong cycled through “Keep on Moving,” repeating the chorus, Lord, I’ve got to keep on moving / Lord, I’ve got to get on down/ Lord, I’ve got to keep on grooving/ Where I can’t be found. The song choice was extra poignant in its message to his two oldest children: Tell Ziggy I’m fine and to keep Cedella in line.

“It was something that he was feeling,” says Griffiths. “I said to Judy and Rita, ‘Boy, this song has been going for so long,’ and that made us even more concerned. To me, he was looking very stressed. [Guitarist] Junior [Marvin] took a picture with one of those instamatic cameras at sound check, and when the picture came out, it didn’t look like the same person.” It’s curious to note that despite the lengthy sound check of the song, Marley did not perform “Keep on Moving” that evening to a live audience.

Like his bandmates, Marvin’s most vivid memory of the Stanley gig comes not from the performance, but during a moment just before the show: “I saw him looking at himself in the mirror, as if to say, ‘I look okay on the outside, but what’s going on in the inside?’”

Around that time, Engler ducked back into the dressing room, which at that point was filled with band members and ganja smoke. Bob had rested for the previous few hours and seemed reborn. “He had some energy now,” says the promoter. “It seemed like somehow he really rose to the occasion.” Engler presented his hero with a plaque recognizing the show as one of the fastest sellouts in the venue’s history. Marley posed for a photo, holding the plaque, as well as two quick shots on the couch snapped by house photographer Rick Malkin.

Another example of his well-documented generosity, before the show Marley approached the scrappy young Ian Wynter – then pulling triple duty with the Wailers as a cook, roadie and apprentice keyboardist – and informed him that his time had finally come. As Wynter (known these days as Natty Wailer) was stringing a guitar, Marley informed him that tonight, he would finally make his live debut with the Wailers.

I’ve been accused on my mission

Jah knows that you shouldn’t do it

For hangin’ me, they were willin’, yeah

And that’s why I’ve got to get on through

Lord, they’re coming after me

Marley’s physical collapse came just as one of his biggest dreams – to be genuinely embraced by Black America – seemed to be in reach. After thrilling more than a million fans across Europe, Pittsburgh was the fifth date on the U.S. leg of the Uprising tour, which – much to the delight of the Wailers themselves – was supposed to be followed by a 60-date tour opening for Stevie Wonder. Marley was unsatisfied that Uprising had only cracked the top 50 on the Billboard 200 chart. At the time, his only hit on Black radio stations had been the title track off Exodus three years earlier.

Frankie Crocker, of leading New York R&B station WBLS and promoter of the two concerts Marley and the Wailers performed during their stay in Manhattan was working to change that. Over two nights at Madison Square Garden, in what seems like a joke three decades later, the legend opened for Lionel Richie and The Commodores, largely embarrassing the headliners on both nights. With the rumble of Family Man’s bass pinning ensnaring onlookers, Marley and the Wailers robbed the spotlight from the soft rockers on both nights – with estimates of as many as 9,000 (nearly half the arena), emptying at intermission.

The surviving band members say that people knew the Wailers for routinely delivered blistering performances, but at those shows, Marley had something to prove. “When he sang, ‘ Get up-get up-get up-get up-get-up, a get up, a get up, a get up now, ’ I literally felt Madison Square Garden swing from east to west, left to right,” remembers Wynter. “The whole building rocked. “

Few of the surviving members have good memories of that final trip to New York. Even before the Marley’s collapse, there seemed to be signs that the dark cloud that had been following him since the attempt on his life in Jamaica in 1976 – a hit attributed to everyone from local gangsters to the CIA – had finally parked itself permanently overhead.

Throughout the band’s career, the entire entourage stayed together, in the same hotel. But due to an apparent lack of rooms on this particular stop of the tour, Marley was separated, booked at the upscale Essex House on Central Park, with Cole, while the band – and even Rita – stayed downtown to the Gramercy Park Hotel.

With Bob’s Island contract expiring, rumors surfaced members of the Gambino crime family were underwriting his touring ambitions in America. True or not, many “hustlers” – as the band refers to them – and even known Jamaica mafia figures started showing up at the Essex House and wherever Marley went in New York. Various accounts report that Marley, while in the hotel, hid away from the crowd in his room, nonplused by – among other things – the rampant cocaine use in his suite. “It was a fuckin’ mess,” says Anderson. “As big as it was, with all the crowds, it was no fun to be a musician in 1980 in the Wailers, despite all the money. There was so many heavy people trying to control us; it was so weird.”

All that seemed to fade when it came time to take the stage in Pittsburgh. Moments before show time, Cole broke the news to the band that this would be the last show of the tour, and, potentially, their last show ever. “We were like, ‘OK, this has gotta be the best show in history. We’re not gonna make one mistake,’” says Marvin.

Before stepping onstage, Marley leaned over to Cole and asked him to stay close, in case of a fall.

I’ve got two boys and a woman

And I know they won’t suffer now

Jah, forgive me for not going back

But I’ll be there anyhow

Yes I’ll be there anyhow

Lord, I got to keep on moving

Part last stand, part test of will, the performance that followed was as lively and audacious as the magnificent New York shows. If the Stanley Theatre audience was oblivious to what was happening, then they had every reason to be: Marley soldiered onto the stage as if the laws of medicine didn’t apply to him. His voice and performance beared their full range and character on meditative favorites like “Natural Mystic” and “Crazy Baldhead” on through the anthemic “War/No More Trouble” medley into his immortal ballad “No Woman No Cry.”

The feeling in the room was so euphoric that Engler began to worry that the swaying, enraptured crowd would collapse his mezzanine. “I don’t know in his mind if he knew that was going to be his last show or not, but he played it like it was,” he says.

Just like the sound check, Marley turned the performance into a solitary experience, interacting little with the ten musicians surrounding him. Live Forever, the newly released double-disc recording of the Stanley Theatre show, is as much a tribute to their ability to balance the job at hand with the drama of the day. “It was kind of a send off party,” says Family Man. “In everyone’s minds, we were meditating on what was happening. So everyone was playing with a special soul.”

Clocking in at an hour and a half, the show doesn’t seem like much of an epic by today’s standards, but for the Wailers, it was a milestone. As the band came on and off stage, delivering then-new songs like “Redemption Song” and “Coming in from the Cold” in one encore, Mowatt remembers silence among the Wailers. “We didn’t want to say a word, we just wanted to do all that we could for the moment,” he says. “I mean, if I could go up there and sing for him, I would have. Our support is only to sing background, but we were there holding him up.”

Immediately after the show, Rita demanded that the powers that be issue a press release canceling the tour due to exhaustion. In less than eight months, Bob would be dead – but not before round after round of chemotherapy robbed him of his dreads, transforming him into the bald man Rita saw in her dream.

“I know how hard Pittsburgh must have been for him,” says Mowatt, “because that must have felt so lonely – because he alone knew what was happening. He alone felt what he was feeling, but it’s not something that he shared, and it’s not something that he allowed us to even share with him. It could be, ‘I don’t want them to hurt,’ because he knew how much it would have hurt us. He knew how much we loved him, and he knew how much it would affect us. It was like a father wouldn’t want his son to know how serious his whole body was hurting on the inside. I don’t think he wanted us to hurt for him.”